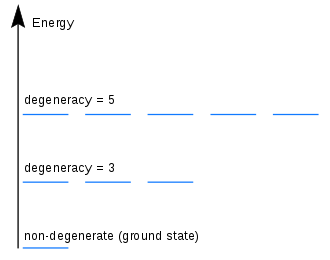

In quantum mechanics, an energy level is degenerate if it corresponds to two or more different measurable states of a quantum system. Conversely, two or more different states of a quantum mechanical system are said to be degenerate if they give the same value of energy upon measurement. The number of different states corresponding to a particular energy level is known as the degree of degeneracy of the level. It is represented mathematically by the Hamiltonian for the system having more than one linearly independent eigenstate with the same energy eigenvalue. When this is the case, energy alone is not enough to characterize what state the system is in, and other quantum numbers are needed to characterize the exact state when distinction is desired. In classical mechanics, this can be understood in terms of different possible trajectories corresponding to the same energy.

Degeneracy plays a fundamental role in quantum statistical mechanics. For an N-particle system in three dimensions, a single energy level may correspond to several different wave functions or energy states. These degenerate states at the same level all have an equal probability of being filled. The number of such states gives the degeneracy of a particular energy level.

Mathematics

The possible states of a quantum mechanical system may be treated mathematically as abstract vectors in a separable, complex Hilbert space, while the observables may be represented by linear Hermitian operators acting upon them. By selecting a suitable basis, the components of these vectors and the matrix elements of the operators in that basis may be determined. If A is a N × N matrix, X a non-zero vector, and λ is a scalar, such that , then the scalar λ is said to be an eigenvalue of A and the vector X is said to be the eigenvector corresponding to λ. Together with the zero vector, the set of all eigenvectors corresponding to a given eigenvalue λ form a subspace of Cn, which is called the eigenspace of λ. An eigenvalue λ which corresponds to two or more different linearly independent eigenvectors is said to be degenerate, i.e., and , where and are linearly independent eigenvectors. The dimension of the eigenspace corresponding to that eigenvalue is known as its degree of degeneracy, which can be finite or infinite. An eigenvalue is said to be non-degenerate if its eigenspace is one-dimensional.

The eigenvalues of the matrices representing physical observables in quantum mechanics give the measurable values of these observables while the eigenstates corresponding to these eigenvalues give the possible states in which the system may be found, upon measurement. The measurable values of the energy of a quantum system are given by the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian operator, while its eigenstates give the possible energy states of the system. A value of energy is said to be degenerate if there exist at least two linearly independent energy states associated with it. Moreover, any linear combination of two or more degenerate eigenstates is also an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian operator corresponding to the same energy eigenvalue. This clearly follows from the fact that the eigenspace of the energy value eigenvalue λ is a subspace (being the kernel of the Hamiltonian minus λ times the identity), hence is closed under linear combinations.

If represents the Hamiltonian operator and and are two eigenstates corresponding to the same eigenvalue E, then

Let , where and are complex(in general) constants, be any linear combination of and . Then,

Effect of degeneracy on the measurement of energy

In the absence of degeneracy, if a measured value of energy of a quantum system is determined, the corresponding state of the system is assumed to be known, since only one eigenstate corresponds to each energy eigenvalue. However, if the Hamiltonian has a degenerate eigenvalue of degree gn, the eigenstates associated with it form a vector subspace of dimension gn. In such a case, several final states can be possibly associated with the same result , all of which are linear combinations of the gn orthonormal eigenvectors .

In this case, the probability that the energy value measured for a system in the state will yield the value is given by the sum of the probabilities of finding the system in each of the states in this basis, i.e.

Degeneracy in different dimensions

This section intends to illustrate the existence of degenerate energy levels in quantum systems studied in different dimensions. The study of one and two-dimensional systems aids the conceptual understanding of more complex systems.

Degeneracy in one dimension

In several cases, analytic results can be obtained more easily in the study of one-dimensional systems. For a quantum particle with a wave function moving in a one-dimensional potential , the time-independent Schrödinger equation can be written as

Since this is an ordinary differential equation, there are two independent eigenfunctions for a given energy at most, so that the degree of degeneracy never exceeds two. It can be proven that in one dimension, there are no degenerate bound states for normalizable wave functions. A sufficient condition on a piecewise continuous potential and the energy is the existence of two real numbers with such that we have . In particular, is bounded below in this criterion.

Degeneracy in two-dimensional quantum systems

Two-dimensional quantum systems exist in all three states of matter and much of the variety seen in three dimensional matter can be created in two dimensions. Real two-dimensional materials are made of monoatomic layers on the surface of solids. Some examples of two-dimensional electron systems achieved experimentally include MOSFET, two-dimensional superlattices of Helium, Neon, Argon, Xenon etc. and surface of liquid Helium. The presence of degenerate energy levels is studied in the cases of particle in a box and two-dimensional harmonic oscillator, which act as useful mathematical models for several real world systems.

Particle in a rectangular plane

Consider a free particle in a plane of dimensions and in a plane of impenetrable walls. The time-independent Schrödinger equation for this system with wave function can be written as

The permitted energy values are

The normalized wave function is

where

So, quantum numbers and are required to describe the energy eigenvalues and the lowest energy of the system is given by

For some commensurate ratios of the two lengths and , certain pairs of states are degenerate. If , where p and q are integers, the states and have the same energy and so are degenerate to each other.

Particle in a square box

In this case, the dimensions of the box and the energy eigenvalues are given by

Since and can be interchanged without changing the energy, each energy level has a degeneracy of at least two when and are different. Degenerate states are also obtained when the sum of squares of quantum numbers corresponding to different energy levels are the same. For example, the three states (nx = 7, ny = 1), (nx = 1, ny = 7) and (nx = ny = 5) all have and constitute a degenerate set.

Degrees of degeneracy of different energy levels for a particle in a square box:

| Degeneracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 1 |

1 2 |

5 5 |

2 |

| 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| 3 1 |

1 3 |

10 10 |

2 |

| 3 2 |

2 3 |

13 13 |

2 |

| 4 1 |

1 4 |

17 17 |

2 |

| 3 | 3 | 18 | 1 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 7 5 1 |

1 5 7 |

50 50 50 |

3 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 8 7 4 1 |

1 4 7 8 |

65 65 65 65 |

4 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 9 7 6 2 |

2 6 7 9 |

85 85 85 85 |

4 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 11 10 5 2 |

2 5 10 11 |

125 125 125 125 |

4 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 14 10 2 |

2 10 14 |

200 200 200 |

3 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 17 13 7 |

7 13 17 |

338 338 338 |

3 |

Particle in a cubic box

In this case, the dimensions of the box and the energy eigenvalues depend on three quantum numbers.

Since , and can be interchanged without changing the energy, each energy level has a degeneracy of at least three when the three quantum numbers are not all equal.

Finding a unique eigenbasis in case of degeneracy

If two operators and commute, i.e. , then for every eigenvector of , is also an eigenvector of with the same eigenvalue. However, if this eigenvalue, say , is degenerate, it can be said that belongs to the eigenspace of , which is said to be globally invariant under the action of .

For two commuting observables A and B, one can construct an orthonormal basis of the state space with eigenvectors common to the two operators. However, is a degenerate eigenvalue of , then it is an eigensubspace of that is invariant under the action of , so the representation of in the eigenbasis of is not a diagonal but a block diagonal matrix, i.e. the degenerate eigenvectors of are not, in general, eigenvectors of . However, it is always possible to choose, in every degenerate eigensubspace of , a basis of eigenvectors common to and .

Choosing a complete set of commuting observables

If a given observable A is non-degenerate, there exists a unique basis formed by its eigenvectors. On the other hand, if one or several eigenvalues of are degenerate, specifying an eigenvalue is not sufficient to characterize a basis vector. If, by choosing an observable , which commutes with , it is possible to construct an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors common to and , which is unique, for each of the possible pairs of eigenvalues {a,b}, then and are said to form a complete set of commuting observables. However, if a unique set of eigenvectors can still not be specified, for at least one of the pairs of eigenvalues, a third observable , which commutes with both and can be found such that the three form a complete set of commuting observables.

It follows that the eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian of a quantum system with a common energy value must be labelled by giving some additional information, which can be done by choosing an operator that commutes with the Hamiltonian. These additional labels required naming of a unique energy eigenfunction and are usually related to the constants of motion of the system.

Degenerate energy eigenstates and the parity operator

The parity operator is defined by its action in the representation of changing r to −r, i.e.

The eigenvalues of P can be shown to be limited to , which are both degenerate eigenvalues in an infinite-dimensional state space. An eigenvector of P with eigenvalue +1 is said to be even, while that with eigenvalue −1 is said to be odd.

Now, an even operator is one that satisfies,

while an odd operator is one that satisfies

Since the square of the momentum operator is even, if the potential V(r) is even, the Hamiltonian is said to be an even operator. In that case, if each of its eigenvalues are non-degenerate, each eigenvector is necessarily an eigenstate of P, and therefore it is possible to look for the eigenstates of among even and odd states. However, if one of the energy eigenstates has no definite parity, it can be asserted that the corresponding eigenvalue is degenerate, and is an eigenvector of with the same eigenvalue as .

Degeneracy and symmetry

The physical origin of degeneracy in a quantum-mechanical system is often the presence of some symmetry in the system. Studying the symmetry of a quantum system can, in some cases, enable us to find the energy levels and degeneracies without solving the Schrödinger equation, hence reducing effort.

Mathematically, the relation of degeneracy with symmetry can be clarified as follows. Consider a symmetry operation associated with a unitary operator S. Under such an operation, the new Hamiltonian is related to the original Hamiltonian by a similarity transformation generated by the operator S, such that , since S is unitary. If the Hamiltonian remains unchanged under the transformation operation S, we have

Now, if is an energy eigenstate,

where E is the corresponding energy eigenvalue.

which means that is also an energy eigenstate with the same eigenvalue E. If the two states and are linearly independent (i.e. physically distinct), they are therefore degenerate.

In cases where S is characterized by a continuous parameter , all states of the form have the same energy eigenvalue.

Symmetry group of the Hamiltonian

The set of all operators which commute with the Hamiltonian of a quantum system are said to form the symmetry group of the Hamiltonian. The commutators of the generators of this group determine the algebra of the group. An n-dimensional representation of the Symmetry group preserves the multiplication table of the symmetry operators. The possible degeneracies of the Hamiltonian with a particular symmetry group are given by the dimensionalities of the irreducible representations of the group. The eigenfunctions corresponding to a n-fold degenerate eigenvalue form a basis for a n-dimensional irreducible representation of the Symmetry group of the Hamiltonian.

Types of degeneracy

Degeneracies in a quantum system can be systematic or accidental in nature.

Systematic or essential degeneracy

This is also called a geometrical or normal degeneracy and arises due to the presence of some kind of symmetry in the system under consideration, i.e. the invariance of the Hamiltonian under a certain operation, as described above. The representation obtained from a normal degeneracy is irreducible and the corresponding eigenfunctions form a basis for this representation.

Accidental degeneracy

It is a type of degeneracy resulting from some special features of the system or the functional form of the potential under consideration, and is related possibly to a hidden dynamical symmetry in the system.[4] It also results in conserved quantities, which are often not easy to identify. Accidental symmetries lead to these additional degeneracies in the discrete energy spectrum. An accidental degeneracy can be due to the fact that the group of the Hamiltonian is not complete. These degeneracies are connected to the existence of bound orbits in classical Physics.

Examples: Coulomb and Harmonic Oscillator potentials

For a particle in a central 1/r potential, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector is a conserved quantity resulting from an accidental degeneracy, in addition to the conservation of angular momentum due to rotational invariance.

For a particle moving on a cone under the influence of 1/r and r2 potentials, centred at the tip of the cone, the conserved quantities corresponding to accidental symmetry will be two components of an equivalent of the Runge-Lenz vector, in addition to one component of the angular momentum vector. These quantities generate SU(2) symmetry for both potentials.

Example: Particle in a constant magnetic field

A particle moving under the influence of a constant magnetic field, undergoing cyclotron motion on a circular orbit is another important example of an accidental symmetry. The symmetry multiplets in this case are the Landau levels which are infinitely degenerate.

Examples

The hydrogen atom

In atomic physics, the bound states of an electron in a hydrogen atom show us useful examples of degeneracy. In this case, the Hamiltonian commutes with the total orbital angular momentum , its component along the z-direction, , total spin angular momentum and its z-component . The quantum numbers corresponding to these operators are , , (always 1/2 for an electron) and respectively.

The energy levels in the hydrogen atom depend only on the principal quantum number n. For a given n, all the states corresponding to have the same energy and are degenerate. Similarly for given values of n and l, the , states with are degenerate. The degree of degeneracy of the energy level En is therefore :, which is doubled if the spin degeneracy is included.

The degeneracy with respect to is an essential degeneracy which is present for any central potential, and arises from the absence of a preferred spatial direction. The degeneracy with respect to is often described as an accidental degeneracy, but it can be explained in terms of special symmetries of the Schrödinger equation which are only valid for the hydrogen atom in which the potential energy is given by Coulomb's law.

Isotropic three-dimensional harmonic oscillator

It is a spinless particle of mass m moving in three-dimensional space, subject to a central force whose absolute value is proportional to the distance of the particle from the centre of force.

It is said to be isotropic since the potential acting on it is rotationally invariant, i.e. :

where is the angular frequency given by .

Since the state space of such a particle is the tensor product of the state spaces associated with the individual one-dimensional wave functions, the time-independent Schrödinger equation for such a system is given by-

So, the energy eigenvalues are

or,

where n is a non-negative integer. So, the energy levels are degenerate and the degree of degeneracy is equal to the number of different sets satisfying

The degeneracy of the -th state can be found by considering the distribution of quanta across , and . Having 0 in gives possibilities for distribution across and . Having 1 quanta in gives possibilities across and and so on. This leads to the general result of and summing over all leads to the degeneracy of the -th state,

As shown, only the ground state where is non-degenerate (ie, has a degeneracy of ).

Removing degeneracy

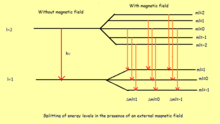

The degeneracy in a quantum mechanical system may be removed if the underlying symmetry is broken by an external perturbation. This causes splitting in the degenerate energy levels. This is essentially a splitting of the original irreducible representations into lower-dimensional such representations of the perturbed system.

Mathematically, the splitting due to the application of a small perturbation potential can be calculated using time-independent degenerate perturbation theory. This is an approximation scheme that can be applied to find the solution to the eigenvalue equation for the Hamiltonian H of a quantum system with an applied perturbation, given the solution for the Hamiltonian H0 for the unperturbed system. It involves expanding the eigenvalues and eigenkets of the Hamiltonian H in a perturbation series. The degenerate eigenstates with a given energy eigenvalue form a vector subspace, but not every basis of eigenstates of this space is a good starting point for perturbation theory, because typically there would not be any eigenstates of the perturbed system near them. The correct basis to choose is one that diagonalizes the perturbation Hamiltonian within the degenerate subspace.

Physical examples of removal of degeneracy by a perturbation

Some important examples of physical situations where degenerate energy levels of a quantum system are split by the application of an external perturbation are given below.

Symmetry breaking in two-level systems

A two-level system essentially refers to a physical system having two states whose energies are close together and very different from those of the other states of the system. All calculations for such a system are performed on a two-dimensional subspace of the state space.

If the ground state of a physical system is two-fold degenerate, any coupling between the two corresponding states lowers the energy of the ground state of the system, and makes it more stable.

If and are the energy levels of the system, such that , and the perturbation is represented in the two-dimensional subspace as the following 2×2 matrix

then the perturbed energies are

Examples of two-state systems in which the degeneracy in energy states is broken by the presence of off-diagonal terms in the Hamiltonian resulting from an internal interaction due to an inherent property of the system include:

- Benzene, with two possible dispositions of the three double bonds between neighbouring Carbon atoms.

- Ammonia molecule, where the Nitrogen atom can be either above or below the plane defined by the three Hydrogen atoms.

- H+

2 molecule, in which the electron may be localized around either of the two nuclei.

Fine-structure splitting

The corrections to the Coulomb interaction between the electron and the proton in a Hydrogen atom due to relativistic motion and spin–orbit coupling result in breaking the degeneracy in energy levels for different values of l corresponding to a single principal quantum number n.

The perturbation Hamiltonian due to relativistic correction is given by

where is the momentum operator and is the mass of the electron. The first-order relativistic energy correction in the basis is given by

Now

where is the fine structure constant.

The spin–orbit interaction refers to the interaction between the intrinsic magnetic moment of the electron with the magnetic field experienced by it due to the relative motion with the proton. The interaction Hamiltonian is

which may be written as

The first order energy correction in the basis where the perturbation Hamiltonian is diagonal, is given by

where is the Bohr radius. The total fine-structure energy shift is given by

for .

Zeeman effect

The splitting of the energy levels of an atom when placed in an external magnetic field because of the interaction of the magnetic moment of the atom with the applied field is known as the Zeeman effect.

Taking into consideration the orbital and spin angular momenta, and , respectively, of a single electron in the Hydrogen atom, the perturbation Hamiltonian is given by

where and . Thus,

Now, in case of the weak-field Zeeman effect, when the applied field is weak compared to the internal field, the spin–orbit coupling dominates and and are not separately conserved. The good quantum numbers are n, l, j and mj, and in this basis, the first order energy correction can be shown to be given by

- , where

is called the Bohr Magneton.Thus, depending on the value of , each degenerate energy level splits into several levels.

In case of the strong-field Zeeman effect, when the applied field is strong enough, so that the orbital and spin angular momenta decouple, the good quantum numbers are now n, l, ml, and ms. Here, Lz and Sz are conserved, so the perturbation Hamiltonian is given by-

assuming the magnetic field to be along the z-direction. So,

For each value of ml, there are two possible values of ms, .

Stark effect

The splitting of the energy levels of an atom or molecule when subjected to an external electric field is known as the Stark effect.

For the hydrogen atom, the perturbation Hamiltonian is

if the electric field is chosen along the z-direction.

The energy corrections due to the applied field are given by the expectation value of in the basis. It can be shown by the selection rules that when and .

The degeneracy is lifted only for certain states obeying the selection rules, in the first order. The first-order splitting in the energy levels for the degenerate states and , both corresponding to n = 2, is given by .

![[{\hat {A}},{\hat {B}}]=0](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ac8a9b22bee144c8197821d7d68194115179a420)

![[P,{\hat {A}}]=0](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/958c103ea4f5faef97e01e55da3740af42847e76)

![[S,H]=0](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f59afb3d2aa673d35ae69f438d95b14b5be031de)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}E_{r}&=(-1/2mc^{2})[E_{n}^{2}+2E_{n}e^{2}\langle 1/r\rangle +e^{4}\langle 1/r^{2}\rangle ]\\&=(-1/2)mc^{2}\alpha ^{4}[-3/(4n^{4})+1/{n^{3}(l+1/2)}]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6a9abd59aa5f43849b602a91e8e4dae5bde8d0d)

![H_{so}=-(e/mc){{\vec {m}}\cdot {\vec {L}}/r^{3}}=[(e^{2}/(m^{2}c^{2}r^{3})){\vec {S}}\cdot {\vec {L}}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b41e22cacf372043a437d2c78bcc2a19472e9dc1)

![H_{so}=(e^{2}/(4m^{2}c^{2}r^{3}))[{\vec {J}}^{2}-{\vec {L}}^{2}-{\vec {S}}^{2}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/da1c7ba3cd031b65302dc86a8dcbc61d14022d97)

![E_{so}=(\hbar ^{2}e^{2})/(4m^{2}c^{2})[j(j+1)-l(l+1)-3/4]/((a_{0})^{3}n^{3}(l(l+1/2)(l+1))]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c13ac4cf47fa3b33a0f3e1ff25441c1e5716b81)

![E_{fs}=-(mc^{2}\alpha ^{4}/(2n^{3}))[1/(j+1/2)-3/4n]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/45ec7ec6d7cf77db9555af6ddefe997f1d1c181e)