In chemistry and thermodynamics, the Van der Waals equation (or Van der Waals equation of state) is an equation of state which extends the ideal gas law to include the effects of interaction between molecules of a gas, as well as accounting for the finite size of the molecules.

The ideal gas law treats gas molecules as point particles that interact with their containers but not each other, meaning they neither take up space nor change kinetic energy during collisions (i.e. all collisions are perfectly elastic). The ideal gas law states that the volume V occupied by n moles of any gas has a pressure P at temperature T given by the following relationship, where R is the gas constant:

To account for the volume occupied by real gas molecules, the Van der Waals equation replaces in the ideal gas law with , where Vm is the molar volume of the gas and b is the volume occupied by the molecules of one mole:

The second modification made to the ideal gas law accounts for interaction between molecules of the gas. The Van der Waals equation includes intermolecular interaction by adding to the observed pressure P in the equation of state a term of the form , where a is a constant whose value depends on the gas.

The complete Van der Waals equation is therefore:

For n moles of gas, it can also be written as:

When the molar volume Vm is large, b becomes negligible in comparison with Vm, a/Vm2 becomes negligible with respect to P, and the Van der Waals equation reduces to the ideal gas law, PVm=RT.

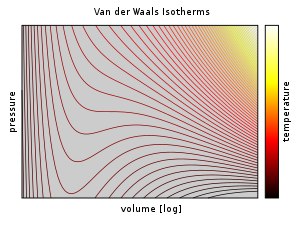

This equation approximates the behavior of real fluids above their critical temperatures and is qualitatively reasonable for their liquid and low-pressure gaseous states at low temperatures. However, near the phase transitions between gas and liquid, in the range of p, V, and T where the liquid phase and the gas phase are in equilibrium, the Van der Waals equation fails to accurately model observed experimental behavior. In particular, p is a constant function of V at given temperatures in these regions. As such, the Van der Waals model is not useful for calculations intended to predict real behavior in regions near critical points. Corrections to address these predictive deficiencies include the equal area rule and the principle of corresponding states.

The equation was named for its developer, the Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals.

Overview and history

The Van der Waals equation is a thermodynamic equation of state based on the theory that fluids are composed of particles with non-zero volumes, and subject to a (not necessarily pairwise) inter-particle attractive force. It was based on work in theoretical physical chemistry performed in the late 19th century by Johannes Diderik van der Waals, who did related work on the attractive force that also bears his name. The equation is known to be based on a traditional set of derivations deriving from Van der Waals' and related efforts, as well as a set of derivation based in statistical thermodynamics, see below.

Van der Waals' early interests were primarily in the field of thermodynamics, where a first influence was Rudolf Clausius's published work on heat in 1857; other significant influences were the writings by James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Willard Gibbs. After initial pursuit of teaching credentials, Van der Waals' undergraduate coursework in mathematics and physics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands led (with significant hurdles) to his acceptance for doctoral studies at Leiden under Pieter Rijke. While his dissertation helps to explain the experimental observation in 1869 by Irish professor of chemistry Thomas Andrews (Queen's University Belfast) of the existence of a critical point in fluids, science historian Martin J. Klein states that it is not clear whether Van der Waals was aware of Andrews' results when he began his doctorate work.

Van der Waals' doctoral research culminated in an 1873 dissertation that provided a semi-quantitative theory describing the gas-liquid change of state and the origin of a critical temperature, Over de Continuïteit van den Gas- en Vloeistoftoestand (Dutch; in English, On the Continuity of the Gas and Liquid State). It was in this dissertation that the first derivations of what we now refer to as the Van der Waals equation appeared. James Clerk Maxwell reviewed and lauded its published content in the British science journal Nature, and Van der Waals began independent work that would result in his receipt of the Nobel Prize in 1910, which emphasized the contribution of his formulation of this "equation of state for gases and liquids".

Equation

The equation relates four state variables: the pressure of the fluid p, the total volume of the fluid's container V, the number of particles N, and the absolute temperature of the system T.

The intensive, microscopic form of the equation is:

where

is the volume of the container occupied by each particle (not the velocity of a particle), and kB is the Boltzmann constant. It introduces two new parameters: a′, a measure of the average attraction between particles, and b′, the volume excluded from v by one particle.

The equation can be also written in extensive, molar form:

or also:

where

is a measure of the average attraction between particles,

is the volume excluded by a mole of particles,

is the number of moles,

is the universal gas constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and NA is the Avogadro constant,

is the specific molar volume.

Also the constant a, b can be expressed in terms of the critical constants:

And the critical constants can be expressed in terms of a, b:

A careful distinction must be drawn between the volume available to a particle and the volume of a particle. In the intensive equation, v equals the total space available to each particle, while the parameter b′ is proportional to the proper volume of a single particle – the volume bounded by the atomic radius. This is subtracted from v because of the space taken up by one particle. In Van der Waals' original derivation, given below, b' is four times the proper volume of the particle. Observe further that the pressure p goes to infinity when the container is completely filled with particles so that there is no void space left for the particles to move; this occurs when V = nb.

Gas mixture

If a mixture of gases is being considered, and each gas has its own (attraction between molecules) and (volume occupied by molecules) values, then and for the mixture can be calculated as

- = total number of moles of gas present,

- for each , = number of moles of gas present, and

and the rule of adding partial pressures becomes invalid if the numerical result of the equation is significantly different from the ideal gas equation .

Reduced form

The Van der Waals equation can also be expressed in terms of reduced properties:

The equation in reduced form is exactly the same for every gas, this is consistent with the Theorem of corresponding states.

This yields a critical compressibility factor of 3/8. Reasons for modification of ideal gas equation: The equation state for ideal gas is PV=RT. In the derivation of ideal gas laws on the basis of kinetic theory of gases some assumption have been made.

Compressibility factor

The compressibility factor for the Van der Waals equation is:

Or in reduced form by substitution of :

At the critical point:

Validity

The Van der Waals equation is mathematically simple, but it nevertheless predicts the experimentally observed transition between vapor and liquid, and predicts critical behaviour. It also adequately predicts and explains the Joule–Thomson effect (temperature change during adiabatic expansion), which is not possible in ideal gas.

Above the critical temperature, TC, the Van der Waals equation is an improvement over the ideal gas law, and for lower temperatures, i.e., T < TC, the equation is also qualitatively reasonable for the liquid and low-pressure gaseous states; however, with respect to the first-order phase transition, i.e., the range of (p, V, T) where a liquid phase and a gas phase would be in equilibrium, the equation appears to fail to predict observed experimental behaviour, in the sense that p is typically observed to be constant as a function of V for a given temperature in the two-phase region. This apparent discrepancy is resolved in the context of vapour–liquid equilibrium: at a particular temperature, there exist two points on the Van der Waals isotherm that have the same chemical potential, and thus a system in thermodynamic equilibrium will appear to traverse a straight line on the p–V diagram as the ratio of vapour to liquid changes. However, in such a system, there are really only two points present (the liquid and the vapour) rather than a series of states connected by a line, so connecting the locus of points is incorrect: it is not an equation of multiple states, but an equation of (a single) state. It is indeed possible to compress a gas beyond the point at which it would typically condense, given the right conditions, and it is also possible to expand a liquid beyond the point at which it would usually boil. Such states are called "metastable" states. Such behaviour is qualitatively (though perhaps not quantitatively) predicted by the Van der Waals equation of state.

However, the values of physical quantities as predicted with the Van der Waals equation of state "are in very poor agreement with experiment", so the model's utility is limited to qualitative rather than quantitative purposes. Empirically-based corrections can easily be inserted into the Van der Waals model (see Maxwell's correction, below), but in so doing, the modified expression is no longer as simple an analytical model; in this regard, other models, such as those based on the principle of corresponding states, achieve a better fit with roughly the same work. Even with its acknowledged shortcomings, the pervasive use of the Van der Waals equation in standard university physical chemistry textbooks makes clear its importance as a pedagogic tool to aid understanding fundamental physical chemistry ideas involved in developing theories of vapour–liquid behavior and equations of state. In addition, other (more accurate) equations of state such as the Redlich–Kwong and Peng–Robinson equation of state are essentially modifications of the Van der Waals equation of state.

Derivation

Textbooks in physical chemistry generally give two derivations of the title equation. One is the conventional derivation that goes back to Van der Waals, a mechanical equation of state that cannot be used to specify all thermodynamic functions; the other is a statistical mechanics derivation that makes explicit the intermolecular potential neglected in the first derivation. A particular advantage of the statistical mechanical derivation is that it yields the partition function for the system, and allows all thermodynamic functions to be specified (including the mechanical equation of state).

Conventional derivation

Consider one mole of gas composed of non-interacting point particles that satisfy the ideal gas law:(see any standard Physical Chemistry text, op. cit.)

Next, assume that all particles are hard spheres of the same finite radius r (the Van der Waals radius). The effect of the finite volume of the particles is to decrease the available void space in which the particles are free to move. We must replace V by V − b, where b is called the excluded volume (per mole) or "co-volume". The corrected equation becomes

The excluded volume is not just equal to the volume occupied by the solid, finite-sized particles, but actually four times the total molecular volume for one mole of a Van der waals' gas. To see this, we must realize that a particle is surrounded by a sphere of radius 2r (two times the original radius) that is forbidden for the centers of the other particles. If the distance between two particle centers were to be smaller than 2r, it would mean that the two particles penetrate each other, which, by definition, hard spheres are unable to do.

The excluded volume for the two particles (of average diameter d or radius r) is

- ,

which, divided by two (the number of colliding particles), gives the excluded volume per particle:

- ,

So b′ is four times the proper volume of the particle. It was a point of concern to Van der Waals that the factor four yields an upper bound; empirical values for b′ are usually lower. Of course, molecules are not infinitely hard, as Van der Waals thought, and are often fairly soft. To obtain the excluded volume per mole we just need to multiply by the number of molecules in a mole, i.e. by the avogadro number:

- .

Next, we introduce a (not necessarily pairwise) attractive force between the particles. Van der Waals assumed that, notwithstanding the existence of this force, the density of the fluid is homogeneous; furthermore, he assumed that the range of the attractive force is so small that the great majority of the particles do not feel that the container is of finite size. Given the homogeneity of the fluid, the bulk of the particles do not experience a net force pulling them to the right or to the left. This is different for the particles in surface layers directly adjacent to the walls. They feel a net force from the bulk particles pulling them into the container, because this force is not compensated by particles on the side where the wall is (another assumption here is that there is no interaction between walls and particles, which is not true, as can be seen from the phenomenon of droplet formation; most types of liquid show adhesion). This net force decreases the force exerted onto the wall by the particles in the surface layer. The net force on a surface particle, pulling it into the container, is proportional to the number density. On considering one mole of gas, the number of particles will be NA

- .

The number of particles in the surface layers is, again by assuming homogeneity, also proportional to the density. In total, the force on the walls is decreased by a factor proportional to the square of the density, and the pressure (force per unit surface) is decreased by

- ,

so that

Upon writing n for the number of moles and nVm = V, the equation obtains the second form given above,

It is of some historical interest to point out that Van der Waals, in his Nobel prize lecture, gave credit to Laplace for the argument that pressure is reduced proportional to the square of the density.

Statistical thermodynamics derivation

The canonical partition function Z of an ideal gas consisting of N = nNA identical (non-interacting) particles, is:

where is the thermal de Broglie wavelength,

with the usual definitions: h is the Planck constant, m the mass of a particle, k the Boltzmann constant and T the absolute temperature. In an ideal gas z is the partition function of a single particle in a container of volume V. In order to derive the Van der Waals equation we assume now that each particle moves independently in an average potential field offered by the other particles. The averaging over the particles is easy because we will assume that the particle density of the Van der Waals fluid is homogeneous. The interaction between a pair of particles, which are hard spheres, is taken to be

r is the distance between the centers of the spheres and d is the distance where the hard spheres touch each other (twice the Van der Waals radius). The depth of the Van der Waals well is .

Because the particles are not coupled under the mean field Hamiltonian, the mean field approximation of the total partition function still factorizes,

- ,

but the intermolecular potential necessitates two modifications to z. First, because of the finite size of the particles, not all of V is available, but only V − Nb', where (just as in the conventional derivation above)

- .

Second, we insert a Boltzmann factor exp[ - ϕ/2kT] to take care of the average intermolecular potential. We divide here the potential by two because this interaction energy is shared between two particles. Thus

The total attraction felt by a single particle is

where we assumed that in a shell of thickness dr there are N/V 4π r2dr particles. This is a mean field approximation; the position of the particles is averaged. In reality the density close to the particle is different than far away as can be described by a pair correlation function. Furthermore, it is neglected that the fluid is enclosed between walls. Performing the integral we get

Hence, we obtain,

From statistical thermodynamics we know that

- ,

so that we only have to differentiate the terms containing . We get

Maxwell equal area rule

Below the critical temperature, the Van der Waals equation seems to predict qualitatively incorrect relationships. Unlike for ideal gases, the p-V isotherms oscillate with a relative minimum (d) and a relative maximum (e). Any pressure between pd and pe appears to have 3 values for the volume, contradicting the experimental observation that two state variables completely determine a one-component system's state. Moreover, the isothermal compressibility is negative between d and e (equivalently ), which cannot describe a system at equilibrium.

To address these problems, James Clerk Maxwell replaced the isotherm between points a and c with a horizontal line positioned so that the areas of the two shaded regions would be equal (replacing the a-d-b-e-c) curve with a straight line from a to c); this portion of the isotherm corresponds to the liquid-vapor equilibrium. The regions of the isotherm from a–d and from c–e are interpreted as metastable states of super-heated liquid and super-cooled vapor, respectively. The equal area rule can be expressed as:

where pV is the vapor pressure (flat portion of the curve), VL is the volume of the pure liquid phase at point a on the diagram, and VG is the volume of the pure gas phase at point c on the diagram. A two-phase mixture at pV will occupy a total volume between VL and VG, as determined by Maxwell's lever rule.

Maxwell justified the rule based on the fact that the area on a pV diagram corresponds to mechanical work, saying that work done on the system in going from c to b should equal work released on going from a to b. This is because the change in free energy A(T,V) equals the work done during a reversible process, and, as a state variable, the free energy must be path-independent. In particular, the value of A at point b should be the same regardless of whether the path taken is from left or right across the horizontal isobar, or follows the original Van der Waals isotherm.

This derivation is not entirely rigorous, since it requires a reversible path through a region of thermodynamic instability, while b is unstable. Nevertheless, modern derivations from chemical potential reach the same conclusion, and it remains a necessary modification to the Van der Waals and to any other analytic equation of state.

From chemical potential

The Maxwell equal area rule can also be derived from an assumption of equal chemical potential μ of coexisting liquid and vapour phases. On the isotherm shown in the above plot, points a and c are the only pair of points which fulfill the equilibrium condition of having equal pressure, temperature and chemical potential. It follows that systems with volumes intermediate between these two points will consist of a mixture of the pure liquid and gas with specific volumes equal to the pure liquid and gas phases at points a and c.

The Van der Waals equation may be solved for VG and VL as functions of the temperature and the vapor pressure pV. Since:

where A is the Helmholtz free energy, it follows that the equal area rule can be expressed as:

- is

Since the gas and liquid volumes are functions of pV and T only, this equation is then solved numerically to obtain pV as a function of temperature (and number of particles N), which may then be used to determine the gas and liquid volumes.

A pseudo-3D plot of the locus of liquid and vapor volumes versus temperature and pressure is shown in the accompanying figure. One sees that the two locii meet at the critical point (1,1,1) smoothly. An isotherm of the Van der Waals fluid taken at T r = 0.90 is also shown where the intersections of the isotherm with the loci illustrate the construct's requirement that the two areas (red and blue, shown) are equal.

Other parameters, forms and applications

Other thermodynamic parameters

We reiterate that the extensive volume V is related to the volume per particle v=V/N where N = nNA is the number of particles in the system. The equation of state does not give us all the thermodynamic parameters of the system. We can take the equation for the Helmholtz energy A

From the equation derived above for lnQ, we find

Where Φ is an undetermined constant, which may be taken from the Sackur–Tetrode equation for an ideal gas to be:

This equation expresses A in terms of its natural variables V and T , and therefore gives us all thermodynamic information about the system. The mechanical equation of state was already derived above

The entropy equation of state yields the entropy (S )

from which we can calculate the internal energy

Similar equations can be written for the other thermodynamic potential and the chemical potential, but expressing any potential as a function of pressure p will require the solution of a third-order polynomial, which yields a complicated expression. Therefore, expressing the enthalpy and the Gibbs energy as functions of their natural variables will be complicated.

Reduced form

Although the material constant a and b in the usual form of the Van der Waals equation differs for every single fluid considered, the equation can be recast into an invariant form applicable to all fluids.

Defining the following reduced variables (fR, fC are the reduced and critical variable versions of f, respectively),

- ,

where

as shown by Salzman.

The first form of the Van der Waals equation of state given above can be recast in the following reduced form:

- )

This equation is invariant for all fluids; that is, the same reduced form equation of state applies, no matter what a and b may be for the particular fluid.

This invariance may also be understood in terms of the principle of corresponding states. If two fluids have the same reduced pressure, reduced volume, and reduced temperature, we say that their states are corresponding. The states of two fluids may be corresponding even if their measured pressure, volume, and temperature are very different. If the two fluids' states are corresponding, they exist in the same regime of the reduced form equation of state. Therefore, they will respond to changes in roughly the same way, even though their measurable physical characteristics may differ significantly.

Cubic equation

The Van der Waals equation is a cubic equation of state; in the reduced formulation the cubic equation is:

At the critical temperature, where we get as expected

For TR < 1, there are 3 values for vR. For TR > 1, there is 1 real value for vR.

The solution of this equation for the case where there are three separate roots may be found at Maxwell construction.

Application to compressible fluids

The equation is also usable as a PVT equation for compressible fluids (e.g. polymers). In this case specific volume changes are small and it can be written in a simplified form:

where p is the pressure, V is specific volume, T is the temperature and A, B, C are parameters.

![A(T,V,N)=-NkT\left[1+\ln \left({\frac {(V-Nb')T^{3/2}}{N\Phi }}\right)\right]-{\frac {a'N^{2}}{V}}.](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee0772e1591ec074c94d8ec125ac5fc2b927d375)

![{\displaystyle S=-\left({\frac {\partial A}{\partial T}}\right)_{N,V}=Nk\left[\ln \left({\frac {(V-Nb')T^{3/2}}{N\Phi }}\right)+{\frac {5}{2}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d26d016c00d464ed8d30641b9c650e5a61cbc404)

![{\displaystyle \gamma _{\pm }={\sqrt[{p+q}]{\gamma _{\mathrm {A} }^{p}\gamma _{\mathrm {B} }^{q}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c66f131bcf882828c4edbb068ee7800812be4e47)

![{\displaystyle K={\frac {[\mathrm {S} ]^{\sigma }[\mathrm {T} ]^{\tau }}{[\mathrm {A} ]^{\alpha }[\mathrm {B} ]^{\beta }}}\times {\frac {\gamma _{\mathrm {S} }^{\sigma }\gamma _{\mathrm {T} }^{\tau }}{\gamma _{\mathrm {A} }^{\alpha }\gamma _{\mathrm {B} }^{\beta }}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/95d7e43431f4648654306641285e434365d7af57)

![{\displaystyle K={\frac {[\mathrm {S} ]^{\sigma }[\mathrm {T} ]^{\tau }}{[\mathrm {A} ]^{\alpha }[\mathrm {B} ]^{\beta }}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/59e684b2a458ef9a608ef9a8d8f9e55473da1e86)