Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon (the most important impurity) are removed from the sourced iron, and alloying elements such as manganese, nickel, chromium, carbon and vanadium are added to produce different grades of steel.

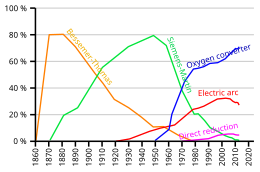

Steelmaking has existed for millennia, but it was not commercialized on a massive scale until the mid-19th century. An ancient process of steelmaking was the crucible process. In the 1850s and 1860s, the Bessemer process and the Siemens-Martin process turned steelmaking into a heavy industry.

Today there are two major commercial processes for making steel, namely basic oxygen steelmaking, which has liquid pig-iron from the blast furnace and scrap steel as the main feed materials, and electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking, which uses scrap steel or direct reduced iron (DRI) as the main feed materials. Oxygen steelmaking is fueled predominantly by the exothermic nature of the reactions inside the vessel; in contrast, in EAF steelmaking, electrical energy is used to melt the solid scrap and/or DRI materials. In recent times, EAF steelmaking technology has evolved closer to oxygen steelmaking as more chemical energy is introduced into the process.

Steelmaking is one of the most carbon emission intensive industries in the world. As of 2020, steelmaking is responsible for about 10 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. To mitigate global warming, the industry will need to find significant reductions in emissions. In 2020, McKinsey identified a number of technologies that could potentially offer some emission reductions, including carbon capture and reuse during manufacturing, and switching to solar and wind energy to either power electric arc furnaces, or produce hydrogen as a cleaner fuel.

History

Steelmaking has played a crucial role in the development of ancient, medieval, and modern technological societies. Early processes of steel making were made during the classical era in Ancient Iran, Ancient China, India, and Rome.

Cast iron is a hard, brittle material that is difficult to work, whereas steel is malleable, relatively easily formed and a versatile material. For much of human history, steel has only been made in small quantities. Since the invention of the Bessemer process in 19th century Britain and subsequent technological developments in injection technology and process control, mass production of steel has become an integral part of the global economy and a key indicator of modern technological development. The earliest means of producing steel was in a bloomery.

Early modern methods of producing steel were often labour-intensive and highly skilled arts. See:

- finery forge, in which the German finery process could be managed to produce steel.

- blister steel and crucible steel.

An important aspect of the Industrial Revolution was the development of large-scale methods of producing forgeable metal (bar iron or steel). The puddling furnace was initially a means of producing wrought iron but was later applied to steel production.

The real revolution in modern steelmaking only began at the end of the 1850s when the Bessemer process became the first successful method of steelmaking in high quantity followed by the open-hearth furnace.

Modern processes for manufacturing of steel

Modern steelmaking processes can be divided into three steps: primary, secondary and tertiary.

Primary steelmaking involves smelting iron into steel. Secondary steelmaking involves adding or removing other elements such as alloying agents and dissolved gases. Tertiary steelmaking involves casting into sheets, rolls or other forms. Multiple techniques are available for each step.

Primary steelmaking

Basic oxygen

Basic oxygen steelmaking is a method of primary steelmaking in which carbon-rich pig iron is melted and converted into steel. Blowing oxygen through molten pig iron converts some of the carbon in the iron into CO−

and CO

2, turning it into steel. Refractories—calcium oxide and magnesium oxide—line the smelting vessel to withstand the high temperature and corrosive nature of the molten metal and slag.

The chemistry of the process is controlled to ensure that impurities

such as silicon and phosphorus are removed from the metal.

The modern process was developed in 1948 by Robert Durrer, as a refinement of the Bessemer converter that replaced air with more efficient oxygen. It reduced the capital cost of the plants and smelting time, and increased labor productivity. Between 1920 and 2000, labour requirements in the industry decreased by a factor of 1000, to just 0.003 man-hours per tonne. in 2013, 70% of global steel output was produced using the basic oxygen furnace. Furnaces can convert up to 350 tons of iron into steel in less than 40 minutes compared to 10–12 hours in an open hearth furnace.

Electric arc

Electric arc furnace steelmaking is the manufacture of steel from scrap or direct reduced iron melted by electric arcs. In an electric arc furnace, a batch ("heat") of iron is loaded into the furnace, sometimes with a "hot heel" (molten steel from a previous heat). Gas burners may be used to assist with the melt. As in basic oxygen steelmaking, fluxes are also added to protect the lining of the vessel and help improve the removal of impurities. Electric arc furnace steelmaking typically uses furnaces of capacity around 100 tonnes that produce steel every 40 to 50 minutes. This process allows larger alloy additions than the basic oxygen method.

HIsarna process

In HIsarna ironmaking process, iron ore is processed almost directly into liquid iron or hot metal. The process is based around a type of blast furnace called a cyclone converter furnace, which makes it possible to skip the process of manufacturing pig iron pellets that is necessary for the basic oxygen steelmaking process. Without the necessity of this preparatory step, the HIsarna process is more energy-efficient and has a lower carbon footprint than traditional steelmaking processes.

Hydrogen reduction

Steel can be produced from direct-reduced iron, which in turn can be produced from iron ore as it undergoes chemical reduction with hydrogen. Renewable hydrogen allows steelmaking without the use of fossil fuels. In 2021, a pilot plant in Sweden tested this process. Direct reduction occurs at 1,500 °F (820 °C). The iron is infused with carbon (from coal) in an electric arc furnace. Hydrogen produced by electrolysis requires approximately 2600 kWh per ton of steel. Costs are estimated to be 20-30% higher than conventional methods. However, the cost of CO2-emissions add to the price of basic oxygen production, and a 2018 study of Science magazine estimates that the prices will break even when that price is €68 per tonne CO2, which is expected to be reached in the 2030s.

Secondary steelmaking

Secondary steelmaking is most commonly performed in ladles. Some of the operations performed in ladles include de-oxidation (or "killing"), vacuum degassing, alloy addition, inclusion removal, inclusion chemistry modification, de-sulphurisation, and homogenisation. It is now common to perform ladle metallurgical operations in gas-stirred ladles with electric arc heating in the lid of the furnace. Tight control of ladle metallurgy is associated with producing high grades of steel in which the tolerances in chemistry and consistency are narrow.

Carbon dioxide emissions

As of 2021, steelmaking is estimated to be responsible for around 11% of the global emissions of carbon dioxide and around 7% of the global greenhouse gas emissions. Making 1 ton of steel emits about 1.8 tons of carbon dioxide. The bulk of these emissions results from the industrial process in which coal is used as the source of carbon that removes oxygen from iron ore in the following chemical reaction, which occurs in a blast furnace:

Fe2O3(s) + 3 CO(g) → 2 Fe(s) + 3 CO2(g)

Additional carbon dioxide emissions result from mining, refining and shipping the ore used, basic oxygen steelmaking, calcination, and the hot blast. Carbon capture and utilization or carbon capture and storage are proposed techniques to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions in the steel industry and reduction of iron ore using green hydrogen rather than carbon. See below for further decarbonization strategies.

Mining and extraction

Coal and iron ore mining are very energy intensive, and result in numerous environmental damages, from pollution, to biodiversity loss, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions. Iron ore is shipped great distances to steel mills.

Blast furnace

To make pure steel, iron and carbon are needed. On its own, iron is not very strong, but a low concentration of carbon - less than 1 percent, depending on the kind of steel, gives the steel its important properties. The carbon in steel is obtained from coal and the iron from iron ore. However, iron ore is a mixture of iron and oxygen, and other trace elements. To make steel, the iron needs to be separated from the oxygen and a tiny amount of carbon needs to be added. Both are accomplished by melting the iron ore at a very high temperature (1,700 degrees Celsius or over 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit) in the presence of oxygen (from the air) and a type of coal called coke. At those temperatures, the iron ore releases its oxygen, which is carried away by the carbon from the coke in the form of carbon dioxide.

Fe2O3(s) + 3 CO(g) → 2 Fe(s) + 3 CO2(g)

The reaction occurs due to the lower (favorable) energy state of carbon dioxide compared to iron oxide, and the high temperatures are needed to achieve the activation energy for this reaction. A small amount of carbon bonds with the iron, forming pig iron, which is an intermediary before steel, as it has carbon content that is too high - around 4%.

Decarburization

To reduce the carbon content in pig iron and obtain the desired carbon content of steel, the pig iron is re-melted and oxygen is blown through in a process called basic oxygen steelmaking, which occurs in a ladle. In this step, the oxygen binds with the undesired carbon, carrying it away in the form of carbon dioxide gas, an additional source of emissions. After this step, the carbon content in the pig iron is lowered sufficiently and steel is obtained.

Calcination

Further carbon dioxide emissions result from the use of limestone, which is melted at high temperatures in a reaction called calcination, which has the following chemical reaction:

CaCO3(s) → CaO(s) + CO2(g)

Carbon dioxide is an additional source of emissions in this reaction. Modern industry has introduced calcium oxide (CaO, quicklime) as an replacement. It acts as a chemical flux, removing impurities (such as Sulfur or Phosphorus (e.g. apatite or fluorapatite)) in the form of slag and keeps emissions of CO2 low. For example, the calcium oxide can react to remove silicon oxide impurities:

SiO2 + CaO → CaSiO3

This use of limestone to provide a flux occurs both in the blast furnace (to obtain pig iron) and in the basic oxygen steel making (to obtain steel).

Hot blast

Further carbon dioxide emissions result from the hot blast, which is used to increase the heat of the blast furnace. The hot blast pumps hot air into the blast furnace where the iron ore is reduced to pig iron, helping to achieve the high activation energy. The hot blast temperature can be from 900 °C to 1300 °C (1600 °F to 2300 °F) depending on the stove design and condition. Oil, tar, natural gas, powdered coal and oxygen can also be injected into the furnace to combine with the coke to release additional energy and increase the percentage of reducing gases present, increasing productivity. If the air in the hot blast is heated by burning fossil fuels, which often is the case, this is an additional source of carbon dioxide emissions.

Strategies for reducing carbon emissions

There are several carbon abatement and decarbonization strategies in the steelmaking industry, depending on the basic manufacturing process used, of which blast furnace/basic oxygen furnace (BF/BOF) is currently the dominant process. Options fall in to three general categories: switching the energy source from fossil fuels to wind and solar, increasing the efficiency of processing, and innovative new technological processes. Most of the latter are still in speculative or experimental stages.

Switching to sustainable energy sources

CO2 emissions vary according to energy sources. When sustainable energy such as wind or solar are used to power the process, in electric arc furnaces, or create hydrogen as a fuel, emissions can be reduced dramatically. European projects from HYBRIT, LKAB, Voestalpine, and ThyssenKrupp are pursuing this strategy.

Top gas recovery in BF/BOF

Top gas from the blast furnace is the gas that is normally exhausted into the air during steelmaking. This gas contains CO2 and is also rich in the reducing agents of H2 and CO. The top gas can be captured, the CO2 removed, and the reducing agents reinjected into the blast furnace.

One study claims this process can reduce BF CO2 emissions by 75%, another study states that the emissions are reduced by 56.5% with the carbon capture and storage and reduced by 26.2% if only the recycling of the reducing agents is used. To keep the carbon captured from entering the atmosphere, a method of storing it or using it would have to be found.

Another way to use the top gas would be in a top recovery turbine which then generates electricity, which could be used to reduce the energy intensity of the process, if electric arc smelting is used. Carbon could also be captured from gasses in the coke oven. Currently, separating the CO2 from other gasses and components in the system, and the high cost of the equipment and infrastructure changes needed, have kept this strategy minimal, but the potential for emission reduction has been estimated to be up to 65% to 80%.

Scrap-use in BF/BOF

Scrap in steelmaking refers to steel that has either reached its end of life use or was generated during the manufacture of steel components. Steel is easy to separate and recycle due to its inherent magnetism and using scrap avoids the emissions of 1.5 tons of CO2 for every ton of scrap used. Currently, steel recycling is high, with all the scrap being collected also being recycled in the steel industry.

H2 enrichment in BF/BOF

In the blast furnace, the iron oxides are reduced by a combination of CO, H2, and carbon. Only around 10% of the iron oxides are reduced by H2. With H2 enrichment processing, the proportion of iron oxides reduced by H2 is increased, so that less carbon is consumed and less CO2 is emitted. This process can reduce emissions by an estimated 20%.

The HIsarna process

The HIsarna ironmaking process was described above as a way of producing iron in a cyclone converter furnace without the pre-processing steps of choking/agglomeration, which reduces the CO2 emissions by around 20%.

Hydrogen plasma

One speculative idea is and ongoing project by SuSteel to develop a hydrogen plasma technology that reduces the oxides with hydrogen, as opposed to with CO or carbon, and melts the iron at high operating temperatures. This project is still at the developmental stage.

Iron ore electrolysis

Another developing possible technology is iron ore electrolysis, where the reducing agent is simply electrons as opposed to H2, CO, or carbon. One method for this is molten oxide electrolysis. Here, the cell consists of an inert anode, a liquid oxide electrolyte (CaO, MgO, etc.), and the molten steel. When heated, the iron ore is reduced to iron and oxygen. Boston Metal is at the semi-industrial stage for this process, with plans to reach commercialization by 2026. Expanding a pilot plant in Woburn, Massachusetts, and building a production facility in Brazil, it was founded by MIT professors Donald Sadoway and Antoine Allanore.

Using biomass in BF/BOF

In steelmaking, coal and coke are used for fuel and iron reduction. Biomass such as charcoal or wood pellets are a potential alternative fuel, but this does not actually reduce emissions, as the burning biomass still emits carbon, it merely provides a "carbon offset", where emissions are "traded" against the sequestration of the source biomass, "ofsetting" emissions by 5% to 28% of current CO2 values.

Offsetting has a very low reputation globally, as cutting down the trees to create the pellets or charcoal does not sequester carbon, it interrupts the natural sequestration the tree was providing. Offsetting is not reduction.

Outlook

Overall, there are a number of innovative methods to reduce CO2 emissions within the steelmaking industry. Some of these, such as top gas recovery and using hydrogen reduction in DRI/EAF are highly feasible with current infrastructure and technology levels. Others, such as hydrogen plasma and iron ore electrolysis are still in the research or semi-industrial stage. Despite these efforts emissions from steel making are not falling in 2023.