| Viet Cong | |

|---|---|

The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green. |

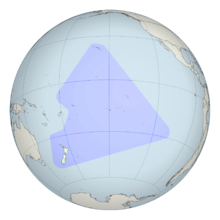

The Viet Cong is a colloquial name used to designate an armed communist organization and movement in South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Formally organized as the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, Viet Cong fought under the direction of North Vietnam against the South Vietnamese and United States governments during the Vietnam War. It had both guerrilla and regular army units, as well as a network of cadres who organized and mobilized peasants in the territory the Viet Cong controlled. During the war, communist fighters and some anti-war activists claimed that the Viet Cong was an insurgency indigenous to the South, while the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments portrayed the group as a tool of North Vietnam. According to Trần Văn Trà, the Viet Cong's top commander, and the post-war Vietnamese government's official history, the Viet Cong followed orders from Hanoi and were part of the People's Army of Vietnam, or North Vietnamese army.

North Vietnam established the National Liberation Front as a front group for the Viet Cong on December 20, 1960, at Tân Lập village in Tây Ninh Province to foment insurgency in the South. Many of the Viet Cong's core members were volunteer "regroupees", southern Viet Minh who had resettled in the North after the Geneva Accord (1954). Hanoi gave the regroupees military training and sent them back to the South along the Ho Chi Minh trail in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Viet Cong called for the unification of Vietnam and the overthrow of the American backed South Vietnamese government. The Viet Cong's best-known action was the Tet Offensive, an assault on more than 100 South Vietnamese urban centers in 1968, including an attack on the U.S. embassy in Saigon. The offensive riveted the attention of the world's media for weeks, but also overextended the Viet Cong. Later communist offensives were conducted predominantly by the North Vietnamese. The organization officially merged with the Fatherland Front of Vietnam on February 4, 1977, after North and South Vietnam were officially unified under a communist government.

Names

The term Việt Cộng appeared in Saigon newspapers beginning in 1956. It is a contraction of Việt Nam cộng sản (Vietnamese communist). The earliest citation for Viet Cong in English is from 1957. American soldiers referred to the Viet Cong as Victor Charlie or V-C. "Victor" and "Charlie" are both letters in the NATO phonetic alphabet. "Charlie" referred to communist forces in general, both Viet Cong and North Vietnamese.

The official Vietnamese history gives the group's name as the Liberation Army of South Vietnam or the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLFSV; Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam). Many writers shorten this to National Liberation Front (NLF). In 1969, the Viet Cong created the "Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam" (Chính Phủ Cách Mạng Lâm Thời Cộng Hòa Miền Nam Việt Nam), abbreviated PRG. Although the NLF was not officially abolished until 1977, the Viet Cong no longer used the name after the PRG was created. Members generally referred to the Viet Cong as "the Front" (Mặt trận). Today's Vietnamese media most frequently refers to the group as the "Liberation Army of South Vietnam" (Quân Giải phóng Miền Nam Việt Nam) .

History

Origin

By the terms of the Geneva Accord (1954), which ended the Indochina War, France and the Viet Minh agreed to a truce and to a separation of forces. The Viet Minh had become the government of North Vietnam, and military forces of the communists regrouped there. Military forces of the non-communists regrouped in South Vietnam, which became a separate state. Elections on reunification were scheduled for July 1956. A divided Vietnam angered Vietnamese nationalists, but it made the country less of a threat to China. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai negotiated the terms of the ceasefire with France and then imposed them on the Viet Minh.

About 90,000 Viet Minh were evacuated to the North while 5,000 to 10,000 cadre remained in the South, most of them with orders to refocus on political activity and agitation. The Saigon-Cholon Peace Committee, the first Viet Cong front, was founded in 1954 to provide leadership for this group. Other front names used by the Viet Cong in the 1950s implied that members were fighting for religious causes, for example, "Executive Committee of the Fatherland Front", which suggested affiliation with the Hòa Hảo sect, or "Vietnam-Cambodia Buddhist Association". Front groups were favored by the Viet Cong to such an extent that its real leadership remained shadowy until long after the war was over, prompting the expression "the faceless Viet Cong".

Led by Ngô Đình Diệm, South Vietnam refused to sign the Geneva Accord. Arguing that a free election was impossible under the conditions that existed in communist-held territory, Diệm announced in July 1955 that the scheduled election on reunification would not be held. After subduing the Bình Xuyên organized crime gang in the Battle for Saigon in 1955, and the Hòa Hảo and other militant religious sects in early 1956, Diệm turned his attention to the Viet Cong. Within a few months, the Viet Cong had been driven into remote swamps. The success of this campaign inspired U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower to dub Diệm the "miracle man" when he visited the U.S. in May 1957. France withdrew its last soldiers from Vietnam in April 1956.

In March 1956, southern communist leader Lê Duẩn presented a plan to revive the insurgency entitled "The Road to the South" to the other members of the Politburo in Hanoi. He argued adamantly that war with the United States was necessary to achieve unification. But as China and the Soviets both opposed confrontation at this time, Lê Duẩn's plan was rejected and communists in the South were ordered to limit themselves to economic struggle. Leadership divided into a "North first", or pro-Beijing, faction led by Trường Chinh, and a "South first" faction led by Lê Duẩn.

As the Sino-Soviet split widened in the following months, Hanoi began to play the two communist giants off against each other. The North Vietnamese leadership approved tentative measures to revive the southern insurgency in December 1956. Lê Duẩn's blueprint for revolution in the South was approved in principle, but implementation was conditional on winning international support and on modernizing the army, which was expected to take at least until 1959. President Hồ Chí Minh stressed that violence was still a last resort. Nguyễn Hữu Xuyên was assigned military command in the South, replacing Lê Duẩn, who was appointed North Vietnam's acting party boss. This represented a loss of power for Hồ, who preferred the more moderate Võ Nguyên Giáp, who was defense minister.

An assassination campaign, referred to as "extermination of traitors" or "armed propaganda" in communist literature, began in April 1957. Tales of sensational murder and mayhem soon crowded the headlines. Seventeen civilians were killed by machine gun fire at a bar in Châu Đốc in July and in September a district chief was killed with his entire family on a main highway in broad daylight. In October 1957, a series of bombs exploded in Saigon and left 13 Americans wounded.

In a speech given on September 2, 1957, Hồ reiterated the "North first" line of economic struggle. The launch of Sputnik in October boosted Soviet confidence and led to a reassessment of policy regarding Indochina, long treated as a Chinese sphere of influence. In November, Hồ traveled to Moscow with Lê Duẩn and gained approval for a more militant line. In early 1958, Lê Duẩn met with the leaders of "Inter-zone V" (northern South Vietnam) and ordered the establishment of patrols and safe areas to provide logistical support for activity in the Mekong Delta and in urban areas. In June 1958, the Viet Cong created a command structure for the eastern Mekong Delta. French scholar Bernard Fall published an influential article in July 1958 which analyzed the pattern of rising violence and concluded that a new war had begun.

Launches armed struggle

The Communist Party of Vietnam approved a "people's war" on the South at a session in January 1959 and this decision was confirmed by the Politburo in March. In May 1959, Group 559 was established to maintain and upgrade the Ho Chi Minh trail, at this time a six-month mountain trek through Laos. About 500 of the "regroupees" of 1954 were sent south on the trail during its first year of operation. The first arms delivery via the trail, a few dozen rifles, was completed in August 1959.

Two regional command centers were merged to create the Central Office for South Vietnam (Trung ương Cục miền Nam), a unified communist party headquarters for the South. COSVN was initially located in Tây Ninh Province near the Cambodian border. On July 8, the Viet Cong killed two U.S. military advisors at Biên Hòa, the first American dead of the Vietnam War. The "2d Liberation Battalion" ambushed two companies of South Vietnamese soldiers in September 1959, the first large unit military action of the war. This was considered the beginning of the "armed struggle" in communist accounts. A series of uprisings beginning in the Mekong Delta province of Bến Tre in January 1960 created "liberated zones", models of Viet Cong-style government. Propagandists celebrated their creation of battalions of "long-hair troops" (women). The fiery declarations of 1959 were followed by a lull while Hanoi focused on events in Laos (1960–61). Moscow favored reducing international tensions in 1960, as it was election year for the U.S. presidency. Despite this, 1960 was a year of unrest in South Vietnam, with pro-democracy demonstrations inspired by the South Korean student uprising that year and a failed military coup in November.

To counter the accusation that North Vietnam was violating the Geneva Accord, the independence of the Viet Cong was stressed in communist propaganda. The Viet Cong created the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam in December 1960 at Tân Lập village in Tây Ninh as a "united front", or political branch intended to encourage the participation of non-communists. The group's formation was announced by Radio Hanoi and its ten-point manifesto called for, "overthrow the disguised colonial regime of the imperialists and the dictatorial administration, and to form a national and democratic coalition administration." Thọ, a lawyer and the Viet Cong's "neutralist" chairman, was an isolated figure among cadres and soldiers. South Vietnam's Law 10/59, approved in May 1959, authorized the death penalty for crimes "against the security of the state" and featured prominently in Viet Cong propaganda. Violence between the Viet Cong and government forces soon increased drastically from 180 clashes in January 1960 to 545 clashes in September.

By 1960, the Sino-Soviet split was a public rivalry, making China more supportive of Hanoi's war effort. For Chinese leader Mao Zedong, aid to North Vietnam was a way to enhance his "anti-imperialist" credentials for both domestic and international audiences. About 40,000 communist soldiers infiltrated the South in 1961–63. The Viet Cong grew rapidly; an estimated 300,000 members were enrolled in "liberation associations" (affiliated groups) by early 1962. The ratio of Viet Cong to government soldiers jumped from 1:10 in 1961 to 1:5 a year later.

The level of violence in the South jumped dramatically in the fall of 1961, from 50 guerrilla attacks in September to 150 in October. U.S. President John F. Kennedy decided in November 1961 to substantially increase American military aid to South Vietnam. The USS Core arrived in Saigon with 35 helicopters in December 1961. By mid-1962, there were 12,000 U.S. military advisors in Vietnam. The "special war" and "strategic hamlets" policies allowed Saigon to push back in 1962, but in 1963 the Viet Cong regained the military initiative. The Viet Cong won its first military victory against South Vietnamese forces at Ấp Bắc in January 1963.

A landmark party meeting was held in December 1963, shortly after a military coup in Saigon in which Diệm was assassinated. North Vietnamese leaders debated the issue of "quick victory" vs "protracted war" (guerrilla warfare). After this meeting, the communist side geared up for a maximum military effort and the troop strength of the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) increased from 174,000 at the end of 1963 to 300,000 in 1964. The Soviets cut aid in 1964 as an expression of annoyance with Hanoi's ties to China. Even as Hanoi embraced China's international line, it continued to follow the Soviet model of reliance on technical specialists and bureaucratic management, as opposed to mass mobilization. The winter of 1964–1965 was a high-water mark for the Viet Cong, with the Saigon government on the verge of collapse. Soviet aid soared following a visit to Hanoi by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin in February 1965. Hanoi was soon receiving up-to-date surface-to-air missiles. The U.S. would have 200,000 soldiers in South Vietnam by the end of the year.

In January 1966, Australian troops uncovered a tunnel complex that had been used by COSVN. Six thousand documents were captured, revealing the inner workings of the Viet Cong. COSVN retreated to Mimot in Cambodia. As a result of an agreement with the Cambodian government made in 1966, weapons for the Viet Cong were shipped to the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville and then trucked to Viet Cong bases near the border along the "Sihanouk Trail", which replaced the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Many Liberation Army of South Vietnam units operated at night, and employed terror as a standard tactic. Rice procured at gunpoint sustained the Viet Cong. Squads were assigned monthly assassination quotas. Government employees, especially village and district heads, were the most common targets. But there were a wide variety of targets, including clinics and medical personnel. Notable Viet Cong atrocities include the massacre of over 3,000 unarmed civilians at Huế, 48 killed in the bombing of My Canh floating restaurant in Saigon in June 1965 and a massacre of 252 Montagnards in the village of Đắk Sơn in December 1967 using flamethrowers. Viet Cong death squads assassinated at least 37,000 civilians in South Vietnam; the real figure was far higher since the data mostly cover 1967–72. They also waged a mass murder campaign against civilian hamlets and refugee camps; in the peak war years, nearly a third of all civilian deaths were the result of Viet Cong atrocities. Ami Pedahzur has written that "the overall volume and lethality of Vietcong terrorism rivals or exceeds all but a handful of terrorist campaigns waged over the last third of the twentieth century".

Logistics and equipment

Tet Offensive

Major reversals in 1966 and 1967, as well as the growing American presence in Vietnam, inspired Hanoi to consult its allies and reassess strategy in April 1967. While Beijing urged a fight to the finish, Moscow suggested a negotiated settlement. Convinced that 1968 could be the last chance for decisive victory, General Nguyễn Chí Thanh, suggested an all-out offensive against urban centers. He submitted a plan to Hanoi in May 1967. After Thanh's death in July, Giáp was assigned to implement this plan, now known as the Tet Offensive. The Parrot's Beak, an area in Cambodia only 30 miles from Saigon, was prepared as a base of operations. Funeral processions were used to smuggle weapons into Saigon. Viet Cong entered the cities concealed among civilians returning home for Tết. The U.S. and South Vietnamese expected that an announced seven-day truce would be observed during Vietnam's main holiday.

At this point, there were about 500,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam, as well as 900,000 allied forces. General William Westmoreland, the U.S. commander, received reports of heavy troop movements and understood that an offensive was being planned, but his attention was focused on Khe Sanh, a remote U.S. base near the DMZ. In January and February 1968, some 80,000 Viet Cong struck more than 100 towns with orders to "crack the sky" and "shake the Earth." The offensive included a commando raid on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon and a massacre at Huế of about 3,500 residents. House-to-house fighting between Viet Cong and South Vietnamese Rangers left much of Cholon, a section of Saigon, in ruins. The Viet Cong used any available tactic to demoralize and intimidate the population, including the assassination of South Vietnamese commanders. A photo by Eddie Adams showing the summary execution of a Viet Cong in Saigon on February 1 became a symbol of the brutality of the war. In an influential broadcast on February 27, newsman Walter Cronkite stated that the war was a "stalemate" and could be ended only by negotiation.

The offensive was undertaken in the hope of triggering a general uprising, but urban Vietnamese did not respond as the Viet Cong anticipated. About 75,000 communist soldiers were killed or wounded, according to Trần Văn Trà, commander of the "B-2" district, which consisted of southern South Vietnam. "We did not base ourselves on scientific calculation or a careful weighing of all factors, but...on an illusion based on our subjective desires", Trà concluded. Earle G. Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, estimated that Tet resulted in 40,000 communist dead (compared to about 10,600 U.S. and South Vietnamese dead). "It is a major irony of the Vietnam War that our propaganda transformed this debacle into a brilliant victory. The truth was that Tet cost us half our forces. Our losses were so immense that we were unable to replace them with new recruits", said PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng. Tet had a profound psychological impact because South Vietnamese cities were otherwise safe areas during the war. U.S. President Lyndon Johnson and Westmoreland argued that panicky news coverage gave the public the unfair perception that America had been defeated.

Aside from some districts in the Mekong Delta, the Viet Cong failed to create a governing apparatus in South Vietnam following Tet, according to an assessment of captured documents by the U.S. CIA. The breakup of larger Viet Cong units increased the effectiveness of the CIA's Phoenix Program (1967–72), which targeted individual leaders, as well as the Chiêu Hồi Program, which encouraged defections. By the end of 1969, there was little communist-held territory, or "liberated zones", in South Vietnam, according to the official communist military history. There were no predominantly southern units left and 70 percent of communist troops in the South were northerners.

The Viet Cong created an urban front in 1968 called the Alliance of National, Democratic, and Peace Forces. The group's manifesto called for an independent, non-aligned South Vietnam and stated that "national reunification cannot be achieved overnight." In June 1969, the alliance merged with the Viet Cong to form a "Provisional Revolutionary Government" (PRG).

Vietnamization

The Tet Offensive increased American public discontent with participation in the Vietnam War and led the U.S. to gradually withdraw combat forces and to shift responsibility to the South Vietnamese, a process called Vietnamization. Pushed into Cambodia, the Viet Cong could no longer draw South Vietnamese recruits. In May 1968, Trường Chinh urged "protracted war" in a speech that was published prominently in the official media, so the fortunes of his "North first" fraction may have revived at this time. COSVN rejected this view as "lacking resolution and absolute determination." The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 led to intense Sino-Soviet tension and to the withdrawal of Chinese forces from North Vietnam. Beginning in February 1970, Lê Duẩn's prominence in the official media increased, suggesting that he was again top leader and had regained the upper hand in his longstanding rivalry with Trường Chinh. After the overthrow of Prince Sihanouk in March 1970, the Viet Cong faced a hostile Cambodian government which authorized a U.S. offensive against its bases in April. However, the capture of the Plain of Jars and other territory in Laos, as well as five provinces in northeastern Cambodia, allowed the North Vietnamese to reopen the Ho Chi Minh trail. Although 1970 was a much better year for the Viet Cong than 1969, it would never again be more than an adjunct to the PAVN. The 1972 Easter Offensive was a direct North Vietnamese attack across the DMZ between North and South. Despite the Paris Peace Accords, signed by all parties in January 1973, fighting continued. In March, Trà was recalled to Hanoi for a series of meetings to hammer out a plan for an enormous offensive against Saigon.

Fall of Saigon

In response to the anti-war movement, the U.S. Congress passed the Case–Church Amendment to prohibit further U.S. military intervention in Vietnam in June 1973 and reduced aid to South Vietnam in August 1974. With U.S. bombing ended, communist logistical preparations could be accelerated. An oil pipeline was built from North Vietnam to Viet Cong headquarters in Lộc Ninh, about 75 miles northwest of Saigon. (COSVN was moved back to South Vietnam following the Easter Offensive.) The Ho Chi Minh Trail, beginning as a series of treacherous mountain tracks at the start of the war, was upgraded throughout the war, first into a road network driveable by trucks in the dry season, and finally, into paved, all-weather roads that could be used year-round, even during the monsoon. Between the beginning of 1974 and April 1975, with now-excellent roads and no fear of air interdiction, the communists delivered nearly 365,000 tons of war matériel to battlefields, 2.6 times the total for the previous 13 years.

The success of the 1973–74 dry season offensive convinced Hanoi to accelerate its timetable. When there was no U.S. response to a successful communist attack on Phước Bình in January 1975, South Vietnamese morale collapsed. The next major battle, at Buôn Ma Thuột in March, was a communist walkover. After the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the PRG moved into government offices there. At the victory parade, Tạng noticed that the units formerly dominated by southerners were missing, replaced by northerners years earlier. The bureaucracy of the Republic of Vietnam was uprooted and authority over the South was assigned to the PAVN. People considered tainted by association with the former South Vietnamese government were sent to re-education camps, despite the protests of the non-communist PRG members including Tạng. Without consulting the PRG, North Vietnamese leaders decided to rapidly dissolve the PRG at a party meeting in August 1975. North and South were merged as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in July 1976 and the PRG was dissolved. The Viet Cong was merged with the Vietnamese Fatherland Front on February 4, 1977.

Relationship with Hanoi

Activists opposing American involvement in Vietnam said that the Viet Cong was a nationalist insurgency indigenous to the South. They said that the Viet Cong was composed of several parties—the People's Revolutionary Party, the Democratic Party and the Radical Socialist Party—and that Viet Cong chairman Nguyễn Hữu Thọ was not a communist.

Anti-communists countered that the Viet Cong was merely a front for Hanoi. They said some statements issued by communist leaders in the 1980s and 1990s suggested that southern communist forces were influenced by Hanoi. According to the memoirs of Trần Văn Trà, the Viet Cong's top commander and PRG defense minister, he followed orders issued by the "Military Commission of the Party Central Committee" in Hanoi, which in turn implemented resolutions of the Politburo. Trà himself was deputy chief of staff for the PAVN before being assigned to the South. The official Vietnamese history of the war states that "The Liberation Army of South Vietnam [Viet Cong] is a part of the People's Army of Vietnam".