End-of-life care refers to health care provided in the time leading up to a person's death. End-of-life care can be provided in the hours, days, or months before a person dies and encompasses care and support for a person's mental and emotional needs, physical comfort, spiritual needs, and practical tasks.

EoLC is most commonly provided at home, in the hospital, or in a long-term care facility with care being provided by family members, nurses, social workers, physicians, and other support staff. Facilities may also have palliative or hospice care teams that will provide end-of-life care services. Decisions about end-of-life care are often informed by medical, financial and ethical considerations.

In most advanced countries, medical spending on people in the last twelve months of life makes up roughly 10% of total aggregate medical spending, while those in the last three years of life can cost up to 25%.

Medical

Advanced care planning

Advances in medicine in the last few decades have provided us with an increasing number of options to extend a person's life and highlighted the importance of ensuring that an individual's preferences and values for end-of-life care are honored. Advanced care planning is the process by which a person of any age is able to provide their preferences and ensure that their future medical treatment aligns with their personal values and life goals. It is typically a continual process, with ongoing discussions about a patient's current prognosis and conditions as well as conversations about medical dilemmas and options. A person will typically have these conversations with their doctor and ultimately record their preferences in an advance healthcare directive. An advance healthcare directive is a legal document that either documents a person's decisions about desired treatment or indicates who a person has entrusted to make their care decisions for them. The two main types of advanced directives are a living will and durable power of attorney for healthcare. A living will includes a person's decisions regarding their future care, a majority of which address resuscitation and life support but may also delve into a patients’ preferences regarding hospitalization, pain control, and specific treatments that they may undergo in the future. The living will will typically take effect when a patient is terminally ill with low chances of recovery. A durable power of attorney for healthcare allows a person to appoint another individual to make healthcare decisions for them under a specified set of circumstances. Combined directives, such as the "Five Wishes", that include components of both the living will and durable power of attorney for healthcare, are being increasingly utilized. Advanced care planning often includes preferences for CPR initiation, nutrition (tube feeding), as well as decisions about the use of machines to keep a person breathing, or support their heart or kidneys. Many studies have reported benefits to patients who complete advanced care planning, specifically noting the improved patient and surrogate satisfaction with communication and decreased clinician distress. However, there is a notable lack of empirical data about what outcome improvements patients experience, as there are considerable discrepancies in what constitutes as advanced care planning and heterogeneity in the outcomes measured. Advanced care planning remains an underutilized tool for patients. Researchers have published data to support the use of new relationship-based and supported decision making models that can increase the use and maximize the benefit of advanced care planning.

End-of-life care conversations

End-of-life care conversations are part of the treatment planning process for terminally ill patients requiring palliative care involving a discussion of a patient's prognosis, specification of goals of care, and individualized treatment planning. Current studies suggest that many patients prioritize proper symptom management, avoidance of suffering, and care that aligns with ethical and cultural standards. Specific conversations can include discussions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ideally occurring before the active dying phase as to not force the conversation during a medical crisis/emergency), place of death, organ donation, and cultural/religious traditions. As there are many factors involved in the end-of-life care decision-making process, the attitudes and perspectives of patients and families may vary. For example, family members may differ over whether life extension or life quality is the main goal of treatment. As it can be challenging for families in the grieving process to make timely decisions that respect the patient's wishes and values, having an established advanced care directive in place can prevent over-treatment, under-treatment, or further complications in treatment management.

Patients and families may also struggle to grasp the inevitability of death, and the differing risks and effects of medical and non-medical interventions available for end-of-life care. A systematic literature review reviewing the frequency of end-of-life care conversations between COPD patients and clinicians found that conversations regarding end-of-life care often occur when a patient has advanced stage disease and occur at a low frequency. To prevent interventions that are not in accordance with the patient's wishes, end-of-life care conversations and advanced care directives can allow for the care they desire, as well as help prevent confusion and strain for family members.

In the case of critically ill babies, parents are able to participate more in decision making if they are presented with options to be discussed rather than recommendations by the doctor. Utilizing this style of communication also leads to less conflict with doctors and might help the parents cope better with the eventual outcomes.

Signs of dying

The National Cancer Institute in the United States (US) advises that the presence of some of the following signs may indicate that death is approaching:

- Drowsiness, increased sleep, and/or unresponsiveness (caused by changes in the patient's metabolism).

- Confusion about time, place, and/or identity of loved ones; restlessness; visions of people and places that are not present; pulling at bed linen or clothing (caused in part by changes in the patient's metabolism).

- Decreased socialization and withdrawal (caused by decreased oxygen to the brain, decreased blood flow, and mental preparation for dying).

- Changes in breathing (indicate neurologic compromise and impending death) and accumulation of upper airway secretions (resulting in crackling and gurgling breath sounds)

- Decreased need for food and fluids, and loss of appetite (caused by the body's need to conserve energy and its decreasing ability to use food and fluids properly).

- Decreased oral intake and impaired swallowing (caused by general physical weakness and metabolic disturbances, including but not limited to hypercalcemia)

- Loss of bladder or bowel control (caused by the relaxing of muscles in the pelvic area).

- Darkened urine or decreased amount of urine (caused by slowing of kidney function and/or decreased fluid intake).

- Skin becoming cool to the touch, particularly the hands and feet; skin may become bluish in color, especially on the underside of the body (caused by decreased circulation to the extremities).

- Rattling or gurgling sounds while breathing, which may be loud (death rattle); breathing that is irregular and shallow; decreased number of breaths per minute; breathing that alternates between rapid and slow (caused by congestion from decreased fluid consumption, a buildup of waste products in the body, and/or a decrease in circulation to the organs).

- Turning of the head toward a light source (caused by decreasing vision).

- Increased difficulty controlling pain (caused by progression of the disease).

- Involuntary movements (called myoclonus)

- Increased heart rate

- Hypertension followed by hypotension

- Loss of reflexes in the legs and arms

Symptoms management

The following are some of the most common potential problems that can arise in the last days and hours of a patient's life:

- Pain

- Typically controlled with opioids, like morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone or, in the United Kingdom, diamorphine. High doses of opioids can cause respiratory depression, and this risk increases with concomitant use of alcohol and other sedatives. Careful use of opioids is important to improve the patient's quality of life while avoiding overdoses.

- Agitation

- Delirium, terminal anguish, restlessness (e.g. thrashing, plucking, or twitching). Typically controlled using clonazepam or midazolam, antipsychotics such as haloperidol or levomepromazine may also be used instead of, or concomitantly with benzodiazepines. Symptoms may also sometimes be alleviated by rehydration, which may reduce the effects of some toxic drug metabolites.

- Respiratory tract secretions

- Saliva and other fluids can accumulate in the oropharynx and upper airways when patients become too weak to clear their throats, leading to a characteristic gurgling or rattle-like sound ("death rattle"). While apparently not painful for the patient, the association of this symptom with impending death can create fear and uncertainty for those at the bedside. The secretions may be controlled using drugs such as hyoscine butylbromide, glycopyrronium, or atropine. Rattle may not be controllable if caused by deeper fluid accumulation in the bronchi or the lungs, such as occurs with pneumonia or some tumours.

- Nausea and vomiting

- Typically controlled using haloperidol, metoclopramide, ondansetron, cyclizine; or other anti-emetics.

- Dyspnea (breathlessness)

- Typically controlled with opioids, like morphine, fentanyl or, in the United Kingdom, diamorphine

Constipation

- Low food intake and opioid use can lead to constipation which can then result in agitation, pain, and delirium. Laxatives and stool softeners are used to prevent constipation. In patients with constipation, the dose of laxatives will be increased to relieve symptoms. Methylnaltrexone is approved to treat constipation due to opioid use.

Other symptoms that may occur, and may be mitigated to some extent, include cough, fatigue, fever, and in some cases bleeding.

Medication administration

Subcutaneous injections are one preferred means of delivery when it has become difficult for patients to swallow or to take pills orally, and if repeated medication is needed, a syringe driver (or infusion pump in the US) is often likely to be used, to deliver a steady low dose of medication. In some settings, such as the home or hospice, sublingual routes of administration may be used for most prescriptions and medications.

Another means of medication delivery, available for use when the oral route is compromised, is a specialized catheter designed to provide comfortable and discreet administration of ongoing medications via the rectal route. The catheter was developed to make rectal access more practical and provide a way to deliver and retain liquid formulations in the distal rectum so that health practitioners can leverage the established benefits of rectal administration. Its small flexible silicone shaft allows the device to be placed safely and remain comfortably in the rectum for repeated administration of medications or liquids. The catheter has a small lumen, allowing for small flush volumes to get medication to the rectum. Small volumes of medications (under 15mL) improve comfort by not stimulating the defecation response of the rectum and can increase the overall absorption of a given dose by decreasing pooling of medication and migration of medication into more proximal areas of the rectum where absorption can be less effective.

Integrated pathways

Integrated care pathways are an organizational tool used by healthcare professionals to clearly define the roles of each team-member and coordinate how and when care will be provided. These pathways are utilized to ensure best practices are being utilized for end-of-life care, such as evidence-based and accepted health care protocols, and to list the required features of care for a specific diagnosis or clinical problem. Many institutions have a predetermined pathway for end of life care, and clinicians should be aware of and make use of these plans when possible. In the United Kingdom, end-of-life care pathways are based on the Liverpool Care Pathway. Originally developed to provide evidence based care to dying cancer patients, this pathway has been adapted and used for a variety of chronic conditions at clinics in the UK and internationally. Despite its increasing popularity, the 2016 Cochrane Review, which only analyzed one trial, showed limited evidence in the form of high-quality randomized clinical trials to measure the effectiveness of end-of-life care pathways on clinical outcomes, physical outcomes, and emotional/psychological outcomes. The BEACON Project group developed an integrated care pathway entitled the Comfort Care Order Set, which delineates care for the last days of life in either a hospice or acute care inpatient setting. This order set was implemented and evaluated in a multisite system throughout six United States Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, and the study found increased orders for opioid medication post-pathway implementation, as well as more orders for antipsychotic medications, more patients undergoing palliative care consultations, more advance directives, and increased sublingual drug administration. The intervention did not, however, decrease the proportion of deaths that occurred in an ICU setting or the utilization of restraints around death.

Home-based end-of-life care

While not possible for every person needing care, surveys of the general public suggest most people would prefer to die at home. In the period from 2003 to 2017, the number of deaths at home in the United States increased from 23.8% to 30.7%, while the number of deaths in the hospital decreased from 39.7% to 29.8%. Home-based end-of-life care may be delivered in a number of ways, including by an extension of a primary care practice, by a palliative care practice, and by home care agencies such as Hospice. High-certainty evidence indicates that implementation of home-based end-of-life care programs increases the number of adults who will die at home and slightly improves their satisfaction at a one-month follow-up. There is low-certainty evidence that there may be very little or no difference in satisfaction of the person needing care for longer term (6 months). The number of people who are admitted to hospital during an end-of-life care program is not known. In addition, the impact of home-based end-of-life care on caregivers, healthcare staff, and health service costs is not clear, however, there is weak evidence to suggest that this intervention may reduce health care costs by a small amount.

Disparities in end-of-life care

Not all groups in society have good access to end-of-life care. A systematic review conducted in 2021 investigated the end of life care experiences of people with severe mental illness, including those with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The research found that individuals with a severe mental illness were unlikely to receive the most appropriate end of life care. The review recommended that there needs to be close partnerships and communication between mental health and end of life care systems, and these teams need to find ways to support people to die where they choose. More training, support and supervision needs to be available for professionals working in end of life care; this could also decrease prejudice and stigma against individuals with severe mental illness at the end of life, notably in those who are homeless. In addition, studies have shown that minority patients face several additional barriers to receiving quality end-of-life care. Minority patients are prevented from accessing care at an equitable rate for a variety of reasons including: individual discrimination from caregivers, cultural insensitivity, racial economic disparities, as well as medical mistrust.

Non-medical

Family and friends

Family members are often uncertain as to what they should be doing when a person is dying. Many gentle, familiar daily tasks, such as combing hair, putting lotion on delicate skin, and holding hands, are comforting and provide a meaningful method of communicating love to a dying person.

Family members may be suffering emotionally due to the impending death. Their own fear of death may affect their behavior. They may feel guilty about past events in their relationship with the dying person or feel that they have been neglectful. These common emotions can result in tension, fights between family members over decisions, worsened care, and sometimes (in what medical professionals call the "Daughter from California syndrome") a long-absent family member arrives while a patient is dying to demand inappropriately aggressive care.

Family members may also be coping with unrelated problems, such as physical or mental illness, emotional and relationship issues, or legal difficulties. These problems can limit their ability to be involved, civil, helpful, or present.

Spirituality and religion

Spirituality is thought to be of increased importance to an individual's wellbeing during a terminal illness or toward the end-of-life. Pastoral/spiritual care has a particular significance in end of life care, and is considered an essential part of palliative care by the WHO. In palliative care, responsibility for spiritual care is shared by the whole team, with leadership given by specialist practitioners such as pastoral care workers. The palliative care approach to spiritual care may, however, be transferred to other contexts and to individual practice.

Spiritual, cultural, and religious beliefs may influence or guide patient preferences regarding end-of-life care. Healthcare providers caring for patients at the end of life can engage family members and encourage conversations about spiritual practices to better address the different needs of diverse patient populations. Studies have shown that people who identify as religious also report higher levels of well-being. Religion has also been shown to be inversely correlated with depression and suicide. While religion provides some benefits to patients, there is some evidence of increased anxiety and other negative outcomes in some studies. While spirituality has been associated with less aggressive end-of-life care, religion has been associated with an increased desire for aggressive care in some patients. Despite these varied outcomes, spiritual and religious care remains an important aspect of care for patients. Studies have shown that barriers to providing adequate spiritual and religious care include a lack of cultural understanding, limited time, and a lack of formal training or experience.

Many hospitals, nursing homes, and hospice centers have chaplains who provide spiritual support and grief counseling to patients and families of all religious and cultural backgrounds.

Ageism

The World Health Organization defines ageism as "the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) towards others or ourselves based on age." A systematic review in 2017 showed that negative attitudes amongst nurses towards older individuals were related to the characteristics of the older adults and their demands. This review also highlighted how nurses who had difficulty giving care to their older patients perceived them as "weak, disabled, inflexible, and lacking cognitive or mental ability". Another systematic review considering structural and individual-level effects of ageism found that ageism led to significantly worse health outcomes in 95.5% of the studies and 74.0% of the 1,159 ageism-health associations examined. Studies have also shown that one’s own perception of aging and internalized ageism negatively impacts their health. In the same systematic review, they included this factor as part of their research. It was concluded that 93.4% of their total 142 associations about self-perceptions of aging show significant associations between ageism and worse health.

Attitudes of healthcare professionals

End-of-life care is an interdisciplinary endeavor involving physicians, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists and social workers. Depending on the facility and level of care needed, the composition of the interprofessional team can vary. Health professional attitudes about end-of-life care depend in part on the provider's role in the care team.

Physicians generally have favorable attitudes towards Advance Directives, which are a key facet of end-of-life care. Medical doctors who have more experience and training in end-of-life care are more likely to cite comfort in having end-of-life-care discussions with patients. Those physicians who have more exposure to end-of-life care also have a higher likelihood of involving nurses in their decision-making process.

A systematic review assessing end-of-life conversations between heart failure patients and healthcare professionals evaluated physician attitudes and preferences towards end-of-life care conversations. The study found that physicians found difficulty initiating end-of-life conversations with their heart failure patients, due to physician apprehension over inducing anxiety in patients, the uncertainty in a patient's prognosis, and physicians awaiting patient cues to initiate end-of-life care conversations.

Although physicians make official decisions about end-of-life care, nurses spend more time with patients and often know more about patient desires and concerns. In a Dutch national survey study of attitudes of nursing staff about involvement in medical end-of-life decisions, 64% of respondents thought patients preferred talking with nurses than physicians and 75% desired to be involved in end-of-life decision making.

By country

Canada

In 2012, Statistics Canada's General Social Survey on Caregiving and care receiving found that 13% of Canadians (3.7 million) aged 15 and older reported that at some point in their lives they had provided end-of-life or palliative care to a family member or friend. For those in their 50s and 60s, the percentage was higher, with about 20% reporting having provided palliative care to a family member or friend. Women were also more likely to have provided palliative care over their lifetimes, with 16% of women reporting having done so, compared with 10% of men. These caregivers helped terminally ill family members or friends with personal or medical care, food preparation, managing finances or providing transportation to and from medical appointments.

United Kingdom

End of life care has been identified by the UK Department of Health as an area where quality of care has previously been "very variable," and which has not had a high profile in the NHS and social care. To address this, a national end of life care programme was established in 2004 to identify and propagate best practice, and a national strategy document published in 2008. The Scottish Government has also published a national strategy.

In 2006 just over half a million people died in England, about 99% of them adults over the age of 18, and almost two-thirds adults over the age of 75. About three-quarters of deaths could be considered "predictable" and followed a period of chronic illness – for example heart disease, cancer, stroke, or dementia. In all, 58% of deaths occurred in an NHS hospital, 18% at home, 17% in residential care homes (most commonly people over the age of 85), and about 4% in hospices. However, a majority of people would prefer to die at home or in a hospice, and according to one survey less than 5% would rather die in hospital. A key aim of the strategy therefore is to reduce the needs for dying patients to have to go to hospital and/or to have to stay there; and to improve provision for support and palliative care in the community to make this possible. One study estimated that 40% of the patients who had died in hospital had not had medical needs that required them to be there.

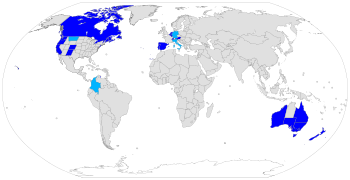

In 2015 and 2010, the UK ranked highest globally in a study of end-of-life care. The 2015 study said "Its ranking is due to comprehensive national policies, the extensive integration of palliative care into the National Health Service, a strong hospice movement, and deep community engagement on the issue." The studies were carried out by the Economist Intelligence Unit and commissioned by the Lien Foundation, a Singaporean philanthropic organisation.

The 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines introduced religion and spirituality among the factors which physicians shall take into account for assessing palliative care needs. In 2016, the UK Minister of Health signed a document which declared people "should have access to personalised care which focuses on the preferences, beliefs and spiritual needs of the individual." As of 2017, more than 47% of the 500,000 deaths in the UK occurred in hospitals.

In 2021 the National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership published their six ambitions for 2021–26. These include fair access to end of life care for everyone regardless of who they are, where they live or their circumstances, and the need to maximise comfort and wellbeing. Informed and timely conversations are also highlighted.

Research funded by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has addressed these areas of need. Examples highlight inequalities faced by several groups and offers recommendations. These include the need for close partnership between services caring for people with severe mental illness, improved understanding of barriers faced by Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities, the provision of flexible palliative care services for children from ethnic minorities or deprived areas.

Other research suggests that giving nurses and pharmacists easier access to electronic patient records about prescribing could help people manage their symptoms at home. A named professional to support and guide patients and carers through the healthcare system could also improve the experience of care at home at the end of life. A synthesised review looking at palliative care in the UK created a resource showing which services were available and grouped them according to their intended purpose and benefit to the patient. They also stated that currently in the UK palliative services are only available to patients with a timeline to death, usually 12 months or less. They found these timelines to often be inaccurate and created barriers to patients accessing appropriate services. They call for a more holistic approach to end of life care which is not restricted by arbitrary timelines.

United States

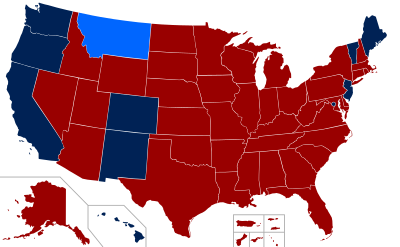

As of 2019, physician-assisted dying is legal in eight states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, Washington) and Washington D.C.

Spending on those in the last twelve months accounts for 8.5% of total aggregate medical spending in the United States.

When considering only those aged 65 and older, estimates show that about 27% of Medicare's annual $327 billion budget ($88 billion) in 2006 goes to care for patients in their final year of life. For the over-65s, between 1992 and 1996, spending on those in their last year of life represented 22% of all medical spending, 18% of all non-Medicare spending, and 25 percent of all Medicaid spending for the poor. These percentages appears to be falling over time, as in 2008, 16.8% of all medical spending on the over 65s went on those in their last year of life.

Predicting death is difficult, which has affected estimates of spending in the last year of life; when controlling for spending on patients who were predicted as likely to die, Medicare spending was estimated at 5% of the total.