Catalysis (/kəˈtæləsɪs/) is the process of change in rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (/ˈkætəlɪst/). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quickly, very small amounts of catalyst often suffice; mixing, surface area, and temperature are important factors in reaction rate. Catalysts generally react with one or more reactants to form intermediates that subsequently give the final reaction product, in the process of regenerating the catalyst.

Catalysis may be classified as either homogeneous, whose components are dispersed in the same phase (usually gaseous or liquid) as the reactant, or heterogeneous, whose components are not in the same phase. Enzymes and other biocatalysts are often considered as a third category.

Catalysis is ubiquitous in chemical industry of all kinds. Estimates are that 90% of all commercially produced chemical products involve catalysts at some stage in the process of their manufacture.

The term "catalyst" is derived from Greek καταλύειν, kataluein, meaning "loosen" or "untie". The concept of catalysis was invented by chemist Elizabeth Fulhame, based on her novel work in oxidation-reduction experiments.

General principles

Example

An illustrative example is the effect of catalysts to speed the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen:

- 2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2

This reaction proceeds because the reaction products are more stable than the starting compound, but this decomposition is so slow that hydrogen peroxide solutions are commercially available. In the presence of a catalyst such as manganese dioxide this reaction proceeds much more rapidly. This effect is readily seen by the effervescence of oxygen. The catalyst is not consumed in the reaction, and may be recovered unchanged and re-used indefinitely. Accordingly, manganese dioxide is said to catalyze this reaction. In living organisms, this reaction is catalyzed by enzymes (proteins that serve as catalysts) such as catalase.

Units

The SI derived unit for measuring the catalytic activity of a catalyst is the katal, which is quantified in moles per second. The productivity of a catalyst can be described by the turnover number (or TON) and the catalytic activity by the turn over frequency (TOF), which is the TON per time unit. The biochemical equivalent is the enzyme unit. For more information on the efficiency of enzymatic catalysis, see the article on enzymes.

Catalytic reaction mechanisms

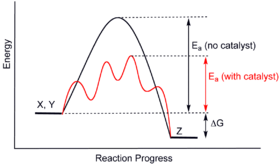

In general, chemical reactions occur faster in the presence of a catalyst because the catalyst provides an alternative reaction mechanism (reaction pathway) having a lower activation energy than the non-catalyzed mechanism. In catalyzed mechanisms, the catalyst usually reacts to form an intermediate, which then regenerates the original catalyst in the process.

As a simple example occurring in the gas phase, the reaction 2 SO2 + O2 → 2 SO3 can be catalyzed by adding nitric oxide. The reaction occurs in two steps:

- 2 NO + O2 → 2 NO2 (rate-determining)

- NO2 + SO2 → NO + SO3 (fast)

The NO catalyst is regenerated. The overall rate is the rate of the slow step

- v = 2k1[NO]2[O2].

An example of heterogeneous catalysis is the reaction of oxygen and hydrogen on the surface of titanium dioxide (TiO2, or titania) to produce water. Scanning tunneling microscopy showed that the molecules undergo adsorption and dissociation. The dissociated, surface-bound O and H atoms diffuse together. The intermediate reaction states are: HO2, H2O2, then H3O2 and the reaction product (water molecule dimers), after which the water molecule desorbs from the catalyst surface.

Reaction energetics

Catalysts enable pathways that differ from the uncatalyzed reactions. These pathways have lower activation energy. Consequently, more molecular collisions have the energy needed to reach the transition state. Hence, catalysts can enable reactions that would otherwise be blocked or slowed by a kinetic barrier. The catalyst may increase the reaction rate or selectivity, or enable the reaction at lower temperatures. This effect can be illustrated with an energy profile diagram.

In the catalyzed elementary reaction, catalysts do not change the extent of a reaction: they have no effect on the chemical equilibrium of a reaction. The ratio of the forward and the reverse reaction rates is unaffected (see also thermodynamics). The second law of thermodynamics describes why a catalyst does not change the chemical equilibrium of a reaction. Suppose there was such a catalyst that shifted an equilibrium. Introducing the catalyst to the system would result in a reaction to move to the new equilibrium, producing energy. Production of energy is a necessary result since reactions are spontaneous only if Gibbs free energy is produced, and if there is no energy barrier, there is no need for a catalyst. Then, removing the catalyst would also result in a reaction, producing energy; i.e. the addition and its reverse process, removal, would both produce energy. Thus, a catalyst that could change the equilibrium would be a perpetual motion machine, a contradiction to the laws of thermodynamics. Thus, catalysts do not alter the equilibrium constant. (A catalyst can however change the equilibrium concentrations by reacting in a subsequent step. It is then consumed as the reaction proceeds, and thus it is also a reactant. Illustrative is the base-catalyzed hydrolysis of esters, where the produced carboxylic acid immediately reacts with the base catalyst and thus the reaction equilibrium is shifted towards hydrolysis.)

The catalyst stabilizes the transition state more than it stabilizes the starting material. It decreases the kinetic barrier by decreasing the difference in energy between starting material and the transition state. It does not change the energy difference between starting materials and products (thermodynamic barrier), or the available energy (this is provided by the environment as heat or light).

Related concepts

Some so-called catalysts are really precatalysts. Precatalysts convert to catalysts in the reaction. For example, Wilkinson's catalyst RhCl(PPh3)3 loses one triphenylphosphine ligand before entering the true catalytic cycle. Precatalysts are easier to store but are easily activated in situ. Because of this preactivation step, many catalytic reactions involve an induction period.

In cooperative catalysis, chemical species that improve catalytic activity are called cocatalysts or promoters.

In tandem catalysis two or more different catalysts are coupled in a one-pot reaction.

In autocatalysis, the catalyst is a product of the overall reaction, in contrast to all other types of catalysis considered in this article. The simplest example of autocatalysis is a reaction of type A + B → 2 B, in one or in several steps. The overall reaction is just A → B, so that B is a product. But since B is also a reactant, it may be present in the rate equation and affect the reaction rate. As the reaction proceeds, the concentration of B increases and can accelerate the reaction as a catalyst. In effect, the reaction accelerates itself or is autocatalyzed. An example is the hydrolysis of an ester such as aspirin to a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. In the absence of added acid catalysts, the carboxylic acid product catalyzes the hydrolysis.

A true catalyst can work in tandem with a sacrificial catalyst. The true catalyst is consumed in the elementary reaction and turned into a deactivated form. The sacrificial catalyst regenerates the true catalyst for another cycle. The sacrificial catalyst is consumed in the reaction, and as such, it is not really a catalyst, but a reagent. For example, osmium tetroxide (OsO4) is a good reagent for dihydroxylation, but it is highly toxic and expensive. In Upjohn dihydroxylation, the sacrificial catalyst N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMMO) regenerates OsO4, and only catalytic quantities of OsO4 are needed.

Classification

Catalysis may be classified as either homogeneous or heterogeneous. A homogeneous catalysis is one whose components are dispersed in the same phase (usually gaseous or liquid) as the reactant's molecules. A heterogeneous catalysis is one where the reaction components are not in the same phase. Enzymes and other biocatalysts are often considered as a third category. Similar mechanistic principles apply to heterogeneous, homogeneous, and biocatalysis.

Heterogeneous catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysts act in a different phase than the reactants. Most heterogeneous catalysts are solids that act on substrates in a liquid or gaseous reaction mixture. Important heterogeneous catalysts include zeolites, alumina, higher-order oxides, graphitic carbon, transition metal oxides, metals such as Raney nickel for hydrogenation, and vanadium(V) oxide for oxidation of sulfur dioxide into sulfur trioxide by the contact process.

Diverse mechanisms for reactions on surfaces are known, depending on how the adsorption takes place (Langmuir-Hinshelwood, Eley-Rideal, and Mars-van Krevelen). The total surface area of a solid has an important effect on the reaction rate. The smaller the catalyst particle size, the larger the surface area for a given mass of particles.

A heterogeneous catalyst has active sites, which are the atoms or crystal faces where the reaction actually occurs. Depending on the mechanism, the active site may be either a planar exposed metal surface, a crystal edge with imperfect metal valence, or a complicated combination of the two. Thus, not only most of the volume but also most of the surface of a heterogeneous catalyst may be catalytically inactive. Finding out the nature of the active site requires technically challenging research. Thus, empirical research for finding out new metal combinations for catalysis continues.

For example, in the Haber process, finely divided iron serves as a catalyst for the synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. The reacting gases adsorb onto active sites on the iron particles. Once physically adsorbed, the reagents undergo chemisorption that results in dissociation into adsorbed atomic species, and new bonds between the resulting fragments form in part due to their closeness. In this way the particularly strong triple bond in nitrogen is broken, which would be extremely uncommon in the gas phase due to its high activation energy. Thus, the activation energy of the overall reaction is lowered, and the rate of reaction increases. Another place where a heterogeneous catalyst is applied is in the oxidation of sulfur dioxide on vanadium(V) oxide for the production of sulfuric acid.

Heterogeneous catalysts are typically "supported," which means that the catalyst is dispersed on a second material that enhances the effectiveness or minimizes its cost. Supports prevent or minimize agglomeration and sintering of small catalyst particles, exposing more surface area, thus catalysts have a higher specific activity (per gram) on support. Sometimes the support is merely a surface on which the catalyst is spread to increase the surface area. More often, the support and the catalyst interact, affecting the catalytic reaction. Supports can also be used in nanoparticle synthesis by providing sites for individual molecules of catalyst to chemically bind. Supports are porous materials with a high surface area, most commonly alumina, zeolites or various kinds of activated carbon. Specialized supports include silicon dioxide, titanium dioxide, calcium carbonate, and barium sulfate.

In slurry reactions, heterogeneous catalysts can be lost by dissolving.

Many heterogeneous catalysts are in fact nanomaterials. Nanomaterial-based catalysts with enzyme-mimicking activities are collectively called as nanozymes.

Electrocatalysts

In the context of electrochemistry, specifically in fuel cell engineering, various metal-containing catalysts are used to enhance the rates of the half reactions that comprise the fuel cell. One common type of fuel cell electrocatalyst is based upon nanoparticles of platinum that are supported on slightly larger carbon particles. When in contact with one of the electrodes in a fuel cell, this platinum increases the rate of oxygen reduction either to water or to hydroxide or hydrogen peroxide.

Homogeneous catalysis

Homogeneous catalysts function in the same phase as the reactants. Typically homogeneous catalysts are dissolved in a solvent with the substrates. One example of homogeneous catalysis involves the influence of H+ on the esterification of carboxylic acids, such as the formation of methyl acetate from acetic acid and methanol. High-volume processes requiring a homogeneous catalyst include hydroformylation, hydrosilylation, hydrocyanation. For inorganic chemists, homogeneous catalysis is often synonymous with organometallic catalysts. Many homogeneous catalysts are however not organometallic, illustrated by the use of cobalt salts that catalyze the oxidation of p-xylene to terephthalic acid.

Organocatalysis

Whereas transition metals sometimes attract most of the attention in the study of catalysis, small organic molecules without metals can also exhibit catalytic properties, as is apparent from the fact that many enzymes lack transition metals. Typically, organic catalysts require a higher loading (amount of catalyst per unit amount of reactant, expressed in mol% amount of substance) than transition metal(-ion)-based catalysts, but these catalysts are usually commercially available in bulk, helping to lower costs. In the early 2000s, these organocatalysts were considered "new generation" and are competitive to traditional metal(-ion)-containing catalysts. Organocatalysts are supposed to operate akin to metal-free enzymes utilizing, e.g., non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding. The discipline organocatalysis is divided into the application of covalent (e.g., proline, DMAP) and non-covalent (e.g., thiourea organocatalysis) organocatalysts referring to the preferred catalyst-substrate binding and interaction, respectively. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2021 was awarded jointly to Benjamin List and David W.C. MacMillan "for the development of asymmetric organocatalysis."

Photocatalysts

Photocatalysis is the phenomenon where the catalyst can receive light to generate an excited state that effect redox reactions. Singlet oxygen is usually produced by photocatalysis. Photocatalysts are components of dye-sensitized solar cells.

Enzymes and biocatalysts

In biology, enzymes are protein-based catalysts in metabolism and catabolism. Most biocatalysts are enzymes, but other non-protein-based classes of biomolecules also exhibit catalytic properties including ribozymes, and synthetic deoxyribozymes.

Biocatalysts can be thought of as an intermediate between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, although strictly speaking soluble enzymes are homogeneous catalysts and membrane-bound enzymes are heterogeneous. Several factors affect the activity of enzymes (and other catalysts) including temperature, pH, the concentration of enzymes, substrate, and products. A particularly important reagent in enzymatic reactions is water, which is the product of many bond-forming reactions and a reactant in many bond-breaking processes.

In biocatalysis, enzymes are employed to prepare many commodity chemicals including high-fructose corn syrup and acrylamide.

Some monoclonal antibodies whose binding target is a stable molecule that resembles the transition state of a chemical reaction can function as weak catalysts for that chemical reaction by lowering its activation energy. Such catalytic antibodies are sometimes called "abzymes".

Significance

Estimates are that 90% of all commercially produced chemical products involve catalysts at some stage in the process of their manufacture. In 2005, catalytic processes generated about $900 billion in products worldwide. Catalysis is so pervasive that subareas are not readily classified. Some areas of particular concentration are surveyed below.

Energy processing

Petroleum refining makes intensive use of catalysis for alkylation, catalytic cracking (breaking long-chain hydrocarbons into smaller pieces), naphtha reforming and steam reforming (conversion of hydrocarbons into synthesis gas). Even the exhaust from the burning of fossil fuels is treated via catalysis: Catalytic converters, typically composed of platinum and rhodium, break down some of the more harmful byproducts of automobile exhaust.

- 2 CO + 2 NO → 2 CO2 + N2

With regard to synthetic fuels, an old but still important process is the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis of hydrocarbons from synthesis gas, which itself is processed via water-gas shift reactions, catalyzed by iron. The Sabatier reaction produces methane from carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Biodiesel and related biofuels require processing via both inorganic and biocatalysts.

Fuel cells rely on catalysts for both the anodic and cathodic reactions.

Catalytic heaters generate flameless heat from a supply of combustible fuel.

Bulk chemicals

Some of the largest-scale chemicals are produced via catalytic oxidation, often using oxygen. Examples include nitric acid (from ammonia), sulfuric acid (from sulfur dioxide to sulfur trioxide by the contact process), terephthalic acid from p-xylene, acrylic acid from propylene or propane and acrylonitrile from propane and ammonia.

The production of ammonia is one of the largest-scale and most energy-intensive processes. In the Haber process nitrogen is combined with hydrogen over an iron oxide catalyst. Methanol is prepared from carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide but using copper-zinc catalysts.

Bulk polymers derived from ethylene and propylene are often prepared via Ziegler-Natta catalysis. Polyesters, polyamides, and isocyanates are derived via acid-base catalysis.

Most carbonylation processes require metal catalysts, examples include the Monsanto acetic acid process and hydroformylation.

Fine chemicals

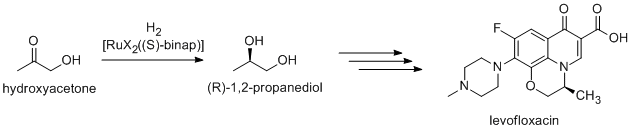

Many fine chemicals are prepared via catalysis; methods include those of heavy industry as well as more specialized processes that would be prohibitively expensive on a large scale. Examples include the Heck reaction, and Friedel–Crafts reactions. Because most bioactive compounds are chiral, many pharmaceuticals are produced by enantioselective catalysis (catalytic asymmetric synthesis). (R)-1,2-Propandiol, the precursor to the antibacterial levofloxacin, can be synthesized efficiently from hydroxyacetone by using catalysts based on BINAP-ruthenium complexes, in Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation:

Food processing

One of the most obvious applications of catalysis is the hydrogenation (reaction with hydrogen gas) of fats using nickel catalyst to produce margarine. Many other foodstuffs are prepared via biocatalysis (see below).

Environment

Catalysis affects the environment by increasing the efficiency of industrial processes, but catalysis also plays a direct role in the environment. A notable example is the catalytic role of chlorine free radicals in the breakdown of ozone. These radicals are formed by the action of ultraviolet radiation on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

- Cl· + O3 → ClO· + O2

- ClO· + O· → Cl· + O2

History

The term "catalyst", broadly defined as anything that increases the rate of a process, is derived from Greek καταλύειν, meaning "to annul," or "to untie," or "to pick up". The concept of catalysis was invented by chemist Elizabeth Fulhame and described in a 1794 book, based on her novel work in oxidation–reduction reactions. The first chemical reaction in organic chemistry that knowingly used a catalyst was studied in 1811 by Gottlieb Kirchhoff, who discovered the acid-catalyzed conversion of starch to glucose. The term catalysis was later used by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in 1835 to describe reactions that are accelerated by substances that remain unchanged after the reaction. Fulhame, who predated Berzelius, did work with water as opposed to metals in her reduction experiments. Other 18th century chemists who worked in catalysis were Eilhard Mitscherlich who referred to it as contact processes, and Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner who spoke of contact action. He developed Döbereiner's lamp, a lighter based on hydrogen and a platinum sponge, which became a commercial success in the 1820s that lives on today. Humphry Davy discovered the use of platinum in catalysis. In the 1880s, Wilhelm Ostwald at Leipzig University started a systematic investigation into reactions that were catalyzed by the presence of acids and bases, and found that chemical reactions occur at finite rates and that these rates can be used to determine the strengths of acids and bases. For this work, Ostwald was awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Vladimir Ipatieff performed some of the earliest industrial scale reactions, including the discovery and commercialization of oligomerization and the development of catalysts for hydrogenation.

Inhibitors, poisons, and promoters

An added substance that lowers the rate is called a reaction inhibitor if reversible and catalyst poisons if irreversible. Promoters are substances that increase the catalytic activity, even though they are not catalysts by themselves.

Inhibitors are sometimes referred to as "negative catalysts" since they decrease the reaction rate. However the term inhibitor is preferred since they do not work by introducing a reaction path with higher activation energy; this would not lower the rate since the reaction would continue to occur by the non-catalyzed path. Instead, they act either by deactivating catalysts or by removing reaction intermediates such as free radicals. In heterogeneous catalysis, coking inhibits the catalyst, which becomes covered by polymeric side products.

The inhibitor may modify selectivity in addition to rate. For instance, in the hydrogenation of alkynes to alkenes, a palladium (Pd) catalyst partly "poisoned" with lead(II) acetate (Pb(CH3CO2)2) can be used. Without the deactivation of the catalyst, the alkene produced would be further hydrogenated to alkane.

The inhibitor can produce this effect by, e.g., selectively poisoning only certain types of active sites. Another mechanism is the modification of surface geometry. For instance, in hydrogenation operations, large planes of metal surface function as sites of hydrogenolysis catalysis while sites catalyzing hydrogenation of unsaturates are smaller. Thus, a poison that covers the surface randomly will tend to lower the number of uncontaminated large planes but leave proportionally smaller sites free, thus changing the hydrogenation vs. hydrogenolysis selectivity. Many other mechanisms are also possible.

Promoters can cover up the surface to prevent the production of a mat of coke, or even actively remove such material (e.g., rhenium on platinum in platforming). They can aid the dispersion of the catalytic material or bind to reagents.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin x&=x-{\frac {x^{3}}{3!}}+{\frac {x^{5}}{5!}}-{\frac {x^{7}}{7!}}+\cdots \\[6mu]&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}}{(2n+1)!}}x^{2n+1}\\[8pt]\cos x&=1-{\frac {x^{2}}{2!}}+{\frac {x^{4}}{4!}}-{\frac {x^{6}}{6!}}+\cdots \\[6mu]&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/396790dc41b52c5381ef1683a279d05ba5d64f79)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\tan x&{}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {U_{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}}x^{2n+1}\\[8mu]&{}=\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n-1}2^{2n}\left(2^{2n}-1\right)B_{2n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n-1}\\[5mu]&{}=x+{\frac {1}{3}}x^{3}+{\frac {2}{15}}x^{5}+{\frac {17}{315}}x^{7}+\cdots ,\qquad {\text{for }}|x|<{\frac {\pi }{2}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d0de1a2399f8c3b723b71c5e24e8f0136fd4bb18)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\csc x&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n+1}2\left(2^{2n-1}-1\right)B_{2n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n-1}\\[5mu]&=x^{-1}+{\frac {1}{6}}x+{\frac {7}{360}}x^{3}+{\frac {31}{15120}}x^{5}+\cdots ,\qquad {\text{for }}0<|x|<\pi .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd4b74fe732906b09b6205ecfa81326222ae0320)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sec x&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {U_{2n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}E_{2n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n}\\[5mu]&=1+{\frac {1}{2}}x^{2}+{\frac {5}{24}}x^{4}+{\frac {61}{720}}x^{6}+\cdots ,\qquad {\text{for }}|x|<{\frac {\pi }{2}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e8d1437d98b6b4d05d4da50fe2e18bd39a7ff9e)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cot x&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}2^{2n}B_{2n}}{(2n)!}}x^{2n-1}\\[5mu]&=x^{-1}-{\frac {1}{3}}x-{\frac {1}{45}}x^{3}-{\frac {2}{945}}x^{5}-\cdots ,\qquad {\text{for }}0<|x|<\pi .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c6645779d6fe606694a0ac157fcdee271c7e795)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}e^{ix}&=\cos x+i\sin x\\[5pt]e^{-ix}&=\cos x-i\sin x.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8d374fafbe34908c7766b67e4c51797589906940)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin x&={\frac {e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{2i}}\\[5pt]\cos x&={\frac {e^{ix}+e^{-ix}}{2}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/590e4a1bbe3ccdb7521fe06a6e5b56e538d4e729)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin z&=\sin x\cosh y+i\cos x\sinh y\\[5pt]\cos z&=\cos x\cosh y-i\sin x\sinh y\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c1646655eab602e234f42df85cae241ffbb867cf)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin \left(x+y\right)&=\sin x\cos y+\cos x\sin y,\\[5mu]\cos \left(x+y\right)&=\cos x\cos y-\sin x\sin y,\\[5mu]\tan(x+y)&={\frac {\tan x+\tan y}{1-\tan x\tan y}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7a94648d4600a711a8851dfaea622a269be4eda5)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin \left(x-y\right)&=\sin x\cos y-\cos x\sin y,\\[5mu]\cos \left(x-y\right)&=\cos x\cos y+\sin x\sin y,\\[5mu]\tan(x-y)&={\frac {\tan x-\tan y}{1+\tan x\tan y}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0a627a03bba700c34bee8de20cfa09d78b127716)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin 2x&=2\sin x\cos x={\frac {2\tan x}{1+\tan ^{2}x}},\\[5mu]\cos 2x&=\cos ^{2}x-\sin ^{2}x=2\cos ^{2}x-1=1-2\sin ^{2}x={\frac {1-\tan ^{2}x}{1+\tan ^{2}x}},\\[5mu]\tan 2x&={\frac {2\tan x}{1-\tan ^{2}x}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d631768e76acdd703625fbcaf9cdf8b8e3e9200f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin \theta &={\frac {2t}{1+t^{2}}},\\[5mu]\cos \theta &={\frac {1-t^{2}}{1+t^{2}}},\\[5mu]\tan \theta &={\frac {2t}{1-t^{2}}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9eb5a515edf456acce4c943b43121632bef4d27)