Passive cooling is a building design approach that focuses on heat gain control and heat dissipation in a building in order to improve the indoor thermal comfort with low or no energy consumption. This approach works either by preventing heat from entering the interior (heat gain prevention) or by removing heat from the building (natural cooling).

Natural cooling utilizes on-site energy, available from the natural environment, combined with the architectural design of building components (e.g. building envelope), rather than mechanical systems to dissipate heat. Therefore, natural cooling depends not only on the architectural design of the building but on how the site's natural resources are used as heat sinks (i.e. everything that absorbs or dissipates heat). Examples of on-site heat sinks are the upper atmosphere (night sky), the outdoor air (wind), and the earth/soil.

Passive cooling is an important tool for design of buildings for climate change adaptation – reducing dependency on energy-intensive air conditioning in warming environments.

Overview

Passive cooling covers all natural processes and techniques of heat dissipation and modulation without the use of energy. Some authors consider that minor and simple mechanical systems (e.g. pumps and economizers) can be integrated in passive cooling techniques, as long they are used to enhance the effectiveness of the natural cooling process. Such applications are also called 'hybrid cooling systems'. The techniques for passive cooling can be grouped in two main categories:

- Preventive techniques that aim to provide protection and/or prevention of external and internal heat gains.

- Modulation and heat dissipation techniques that allow the building to store and dissipate heat gain through the transfer of heat from heat sinks to the climate. This technique can be the result of thermal mass or natural cooling.

Preventive techniques

Protection from or prevention of heat gains encompasses all the design techniques that minimizes the impact of solar heat gains through the building's envelope and of internal heat gains that is generated inside the building due occupancy and equipment. It includes the following design techniques:

- Microclimate and site design - By taking into account the local climate and the site context, specific cooling strategies can be selected to apply which are the most appropriate for preventing overheating through the envelope of the building. The microclimate can play a huge role in determining the most favorable building location by analyzing the combined availability of sun and wind. The bioclimatic chart, the solar diagram and the wind rose are relevant analysis tools in the application of this technique.

- Solar control - A properly designed shading system can effectively contribute to minimizing the solar heat gains. Shading both transparent and opaque surfaces of the building envelope will minimize the amount of solar radiation that induces overheating in both indoor spaces and building's structure. By shading the building structure, the heat gain captured through the windows and envelope will be reduced.

- Building form and layout - Building orientation and an optimized distribution of interior spaces can prevent overheating. Rooms can be zoned within the buildings in order to reject sources of internal heat gain and/or allocating heat gains where they can be useful, considering the different activities of the building. For example, creating a flat, horizontal plan will increase the effectiveness of cross-ventilation across the plan. Locating the zones vertically can take advantage of temperature stratification. Typically, building zones in the upper levels are warmer than the lower zones due to stratification. Vertical zoning of spaces and activities uses this temperature stratification to accommodate zone uses according to their temperature requirements. Form factor (i.e. the ratio between volume and surface) also plays a major role in the building's energy and thermal profile. This ratio can be used to shape the building form to the specific local climate. For example, more compact forms tend to preserve more heat than less compact forms because the ratio of the internal loads to envelope area is significant.

- Thermal insulation - Insulation in the building's envelope will decrease the amount of heat transferred by radiation through the facades. This principle applies both to the opaque (walls and roof) and transparent surfaces (windows) of the envelope. Since roofs could be a larger contributor to the interior heat load, especially in lighter constructions (e.g. building and workshops with roof made out of metal structures), providing thermal insulation can effectively decrease heat transfer from the roof.

- Behavioral and occupancy patterns - Some building management policies such as limiting the number of people in a given area of the building can also contribute effectively to the minimization of heat gains inside a building. Building occupants can also contribute to indoor overheating prevention by: shutting off the lights and equipment of unoccupied spaces, operating shading when necessary to reduce solar heat gains through windows, or dress lighter in order to adapt better to the indoor environment by increasing their thermal comfort tolerance.

- Internal gain control - More energy-efficient lighting and electronic equipment tend to release less energy thus contributing to less internal heat loads inside the space.

Modulation and heat dissipation techniques

The modulation and heat dissipation techniques rely on natural heat sinks to store and remove the internal heat gains. Examples of natural sinks are night sky, earth soil, and building mass. Therefore, passive cooling techniques that use heat sinks can act to either modulate heat gain with thermal mass or dissipate heat through natural cooling strategies.

- Thermal mass - Heat gain modulation of an indoor space can be achieved by the proper use of the building's thermal mass as a heat sink. The thermal mass will absorb and store heat during daytime hours and return it to the space at a later time. Thermal mass can be coupled with night ventilation natural cooling strategy if the stored heat that will be delivered to the space during the evening/night is not desirable.

- Natural cooling - Natural cooling refers to the use of ventilation or natural heat sinks for heat dissipation from indoor spaces. Natural cooling can be separated into five different categories: ventilation, night flushing, radiative cooling, evaporative cooling, and earth coupling.

Ventilation

Ventilation as a natural cooling strategy uses the physical properties of air to remove heat or provide cooling to occupants. In select cases, ventilation can be used to cool the building structure, which subsequently may serve as a heat sink.

- Cross ventilation - The strategy of cross ventilation relies on wind to pass through the building for the purpose of cooling the occupants. Cross ventilation requires openings on two sides of the space, called the inlet and outlet. The sizing and placement of the ventilation inlets and outlets will determine the direction and velocity of cross ventilation through the building. Generally, an equal (or greater) area of outlet openings must also be provided to provide adequate cross ventilation.

- Stack ventilation - Cross ventilation is an effective cooling strategy, however, wind is an unreliable resource. Stack ventilation is an alternative design strategy that relies on the buoyancy of warm air to rise and exit through openings located at ceiling height. Cooler outside air replaces the rising warm air through carefully designed inlets placed near the floor.

These two strategies are part of the ventilative cooling strategies.

One specific application of natural ventilation is night flushing.

Night flushing

Night flushing (also known as night ventilation, night cooling, night purging, or nocturnal convective cooling) is a passive or semi-passive cooling strategy that requires increased air movement at night to cool the structural elements of a building. A distinction may be made between free cooling to chill water and night flushing to cool down building thermal mass. To execute night flushing, one typically keeps the building envelope closed during the day. The building structure's thermal mass acts as a sink through the day and absorbs heat gains from occupants, equipment, solar radiation, and conduction through walls, roofs, and ceilings. At night, when the outside air is cooler, the envelope is opened, allowing cooler air to pass through the building so the stored heat can be dissipated by convection. This process reduces the temperature of the indoor air and of the building's thermal mass, allowing convective, conductive, and radiant cooling to take place during the day when the building is occupied. Night flushing is most effective in climates with a large diurnal swing, i.e. a large difference between the daily maximum and minimum outdoor temperature. For optimal performance, the nighttime outdoor air temperature should fall well below the daytime comfort zone limit of 22 °C (72 °F), and should not have low absolute or specific humidity. In hot, humid climates the dirunal temperature swing is typically small, and the nighttime humidity stays high. Night flushing has limited effectiveness and can introduce high humidity that causes problems and can lead to high energy costs if it is removed by active systems during the day. Thus, night flushing's effectiveness is limited to sufficiently dry climates. For the night flushing strategy to be effective at reducing indoor temperature and energy usage, the thermal mass must be sized sufficiently and distributed over a wide enough surface area to absorb the space's daily heat gains. Also, the total air change rate must be high enough to remove the internal heat gains from the space at night. There are three ways night flushing can be achieved in a building:

- Natural night flushing by opening windows at night, letting wind-driven or buoyancy-driven airflow cool the space, and then closing windows during the day.

- Mechanical night flushing by forcing air mechanically through ventilation ducts at night at a high airflow rate and supplying air to the space during the day at a code-required minimum airflow rate.

- Mixed-mode night flushing through a combination of natural ventilation and mechanical ventilation, also known as mixed-mode ventilation, by using fans to assist the natural nighttime airflow.

These three strategies are part of the ventilative cooling strategies.

There are numerous benefits to using night flushing as a cooling strategy for buildings, including improved comfort and a shift in peak energy load.[22] Energy is most expensive during the day. By implementing night flushing, the usage of mechanical ventilation is reduced during the day, leading to energy and money savings.

There are also a number of limitations to using night flushing, such as usability, security, reduced indoor air quality, humidity, and poor room acoustics. For natural night flushing, the process of manually opening and closing windows every day can be tiresome, especially in the presence of insect screens. This problem can be eased with automated windows or ventilation louvers, such as in the Manitoba Hydro Place. Natural night flushing also requires windows to be open at night when the building is most likely unoccupied, which can raise security issues. If outdoor air is polluted, night flushing can expose occupants to harmful conditions inside the building. In loud city locations, the opening of windows can create poor acoustical conditions inside the building. In humid climates, night flushing can introduce humid air, typically above 90% relative humidity during the coolest part of the night. This moisture can accumulate in the building overnight leading to increased humidity during the day leading to comfort problems and even mold growth.

Radiative cooling

All objects constantly emit and absorb radiant energy. An object will cool by radiation if the net flow is outward, which is the case during the night. At night, the long-wave radiation from the clear sky is less than the long-wave infrared radiation emitted from a building, thus there is a net flow to the sky. Since the roof provides the greatest surface visible to the night sky, designing the roof to act as a radiator is an effective strategy. Types of radiative cooling strategies that utilize the roof surface include direct and indirect, and fluorescent.

- Direct radiant cooling - In a building designed to optimize direct radiation cooling, the building roof acts as a heat sink to absorb the daily internal loads. The roof acts as the best heat sink because it is the greatest surface exposed to the night sky. Radiate heat transfer with the night sky will remove heat from the building roof, thus cooling the building structure. Roof ponds are an example of this strategy. The roof pond design became popular with the development of the Sky thermal system designed by Harold Hay in 1977. There are various designs and configurations for the roof pond system but the concept is the same for all designs. The roof uses water, either plastic bags filled with water or an open pond, as the heat sink while a system of movable insulation panels regulate the mode of heating or cooling. During daytime in the summer, the water on the roof is protected from the solar radiation and ambient air temperature by movable insulation, which allows it to serve as a heat sink and absorb the heat generated inside through the ceiling. At night, the panels are retracted to allow nocturnal radiation between the roof pond and the night sky, thus removing the stored heat. In winter, the process is reversed so that the roof pond is allowed to absorb solar radiation during the day and release it during the night into the space below.

- Indirect radiant cooling - A heat transfer fluid removes heat from the building structure through radiate heat transfer with the night sky. A common design for this strategy involves a plenum between the building roof and the radiator surface. Air is drawn into the building through the plenum, cooled from the radiator, and cools the mass of the building structure. During the day, the building mass acts as a heat sink.

- Fluorescent radiant cooling - An object can be made fluorescent: it will then absorb light at some wavelengths, but radiate the energy away again at other, selected wavelengths. By selectively radiating heat in the infrared atmospheric window, a range of frequencies in which the atmosphere is unusually transparent, an object can effectively use outer space as a heat sink, and cool to well below ambient air temperature.

Evaporative cooling

This design relies on the evaporative process of water to cool the incoming air while simultaneously increasing the relative humidity. A saturated filter is placed at the supply inlet so the natural process of evaporation can cool the supply air. Apart from the energy to drive the fans, water is the only other resource required to provide conditioning to indoor spaces. The effectiveness of evaporative cooling is largely dependent on the humidity of the outside air; dryer air produces more cooling. A study of field performance results in Kuwait revealed that power requirements for an evaporative cooler are approximately 75% less than the power requirements for a conventional packaged unit air-conditioner. As for interior comfort, a study found that evaporative cooling reduced inside air temperature by 9.6 °C compared to outdoor temperature. An innovative passive system uses evaporating water to cool the roof so that a major portion of solar heat does not come inside.

Ancient Egypt used evaporative cooling; for instance, reeds were hung in windows and were moistened with trickling water.

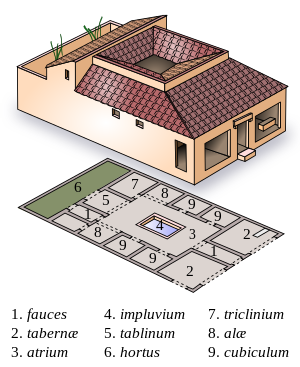

Evaporation from the soil and transpiration from plants also provides cooling; the water released from the plant evaporates. Gardens and potted plants are used to drive cooling, as in the hortus of a domus, the tsubo-niwa of a machiya, and so on.

Earth coupling

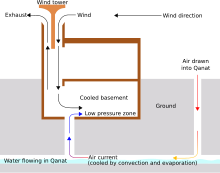

Earth coupling uses the moderate and consistent temperature of the soil to act as a heat sink to cool a building through conduction. This passive cooling strategy is most effective when earth temperatures are cooler than ambient air temperature, such as in hot climates.

- Direct coupling or earth sheltering occurs when a building uses earth as a buffer for the walls. The earth acts as a heat sink and can effectively mitigate temperature extremes. Earth sheltering improves the performance of building envelopes by reducing heat losses and also reduces heat gains by limiting infiltration.

- Indirect coupling means that a building is coupled with the earth by means of earth ducts. An earth duct is a buried tube that acts as avenue for supply air to travel through before entering the building. The supply air is cooled by conductive heat transfer between the tubes and surrounding soil. Therefore, earth ducts will not perform well as a source of cooling unless the soil temperature is lower than the desired room air temperature. Earth ducts typically require long tubes to cool the supply air to an appropriate temperature before entering the building. A fan is required to draw the air from the earth duct into the building. Some of the factors that affect the performance of an earth duct are: duct length, number of bends, thickness of duct wall, depth of duct, diameter of the duct, and air velocity.

In conventional buildings

There are "smart-roof coatings" and "smart windows" for cooling that switches to warming during cold temperatures. The whitest paint formulation can reflect up to 98.1% of sunlight.