The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England during the late 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th century. As in most of the rest of northern Europe, England saw little of these developments until more than a century later within the Northern Renaissance. Renaissance style and ideas were slow to penetrate England, and the Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance. Many scholars see its beginnings in the early 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII. Others argue the Renaissance was already present in England in the late 15th century.

The English Renaissance is different from the Italian Renaissance in several ways. The dominant art forms of the English Renaissance were literature and music. Visual arts in the English Renaissance were much less significant than in the Italian Renaissance. The English period began far later than the Italian, which was moving into Mannerism and the Baroque by the 1550s or earlier.

Literature

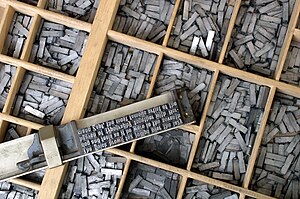

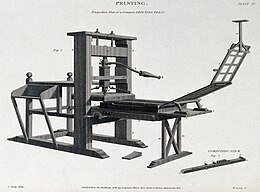

England had a strong tradition of literature in the English vernacular, which gradually increased as English use of the printing press became common by the mid-16th century. This tradition of literature written in English vernacular largely began with the Protestant Reformation's call to let people interpret the Bible for themselves instead of accepting the Catholic Church's interpretation. Discussions on how to translate the Bible so that it could be understood by laymen but still do justice to God's word became contentious, with people arguing how much license could be taken to impart the correct meaning without sacrificing its eloquence. The desire to let people read the Bible for themselves led William Tyndale to publish his own translation in 1526, giving way to Sir Rowland Hill's publication of the Geneva Bible in 1560, marking the re-establishment of the Church of England at the accession of Elizabeth I. These would be predecessors to the King James Version of the Bible.

Another early proponent of literature in the vernacular was Roger Ascham, who was tutor to Princess Elizabeth during her teenage years, and is now often called the "father of English prose." He proposed that speech was the greatest gift to man from God and to speak or write poorly was an affront. The peak of English drama and theatre is said to be the Elizabethan Age; a golden age in English history where the arts, drama and creative work flourished. Morality plays emerged as a distinct dramatic form around 1400 and flourished in the early Elizabethan era in England. By the time of Elizabethan literature, a vigorous literary culture in both drama and poetry included poets such as Edmund Spenser, whose verse epic The Faerie Queene had a strong influence on English literature but was eventually overshadowed by the lyrics of William Shakespeare, Thomas Wyatt and others. Typically, the works of these playwrights and poets circulated in manuscript form for some time before they were published, and above all the plays of English Renaissance theatre were the outstanding legacy of the period. The works of this period are also affected by Henry VIII's declaration of independence from the Catholic Church and technological advances in sailing and cartography, which are reflected in the generally nonreligious themes and various shipwreck adventures of Shakespeare.

The growing population of London, the growing wealth of its people, and their fondness for spectacle produced a dramatic literature of remarkable variety, quality, and extent. Genres of the period included the history play, which depicted English or European history. Shakespeare's plays about the lives of kings, such as Richard III and Henry V, belong to this category, as do Christopher Marlowe's Edward II and George Peele's Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First. History plays dealt with more recent events, like A Larum for London which dramatizes the sack of Antwerp in 1576. Tragedy was a very popular genre. Marlowe's tragedies were exceptionally successful, such as Dr. Faustus and The Jew of Malta. The audiences particularly liked revenge dramas, such as Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. The four tragedies considered to be Shakespeare's greatest (Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth) were composed during this period. The English theatre scene, which performed both for the court and nobility in private performances and a very wide public in the theatres, was the most crowded in Europe, with a host of other playwrights as well as the giant figures of Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. Elizabeth herself was a product of Renaissance humanism trained by Roger Ascham, and wrote occasional poems such as "On Monsieur's Departure" at critical moments of her life. William Shakespeare, whose works include Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, remains one of the most championed authors in English literature. The playwright and poet is widely regarded as the greatest dramatist of all time.

Philosophers and intellectuals included Thomas More and Francis Bacon. Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes wrote on empiricism and materialism, including scientific method and social contract. Bacon's works are seen as developing the scientific method and remained highly influential through the Scientific Revolution. Robert Filmer wrote on the Divine Right of Kings. All the 16th century Tudor monarchs were highly educated, as was much of the nobility, and Italian literature had a considerable following, providing the sources for many of Shakespeare's plays. English thought advanced towards modern science with the Baconian Method. The language of the Book of Common Prayer, first published in 1549, and at the end of the period the Bible had enduring and profound impacts on the English consciousness.

Visual arts

England was slow to produce visual arts in Renaissance styles, and the artists of the Tudor court were mainly imported foreigners until after the end of the Renaissance; Hans Holbein was the outstanding figure. The English Reformation produced a huge programme of iconoclasm that destroyed almost all medieval religious art, and all but ended the skill of painting in England; English art was to be dominated by portrait painting, and then later landscape art, for centuries to come.

The significant English invention was the portrait miniature, which essentially took the techniques of the dying art of the illuminated manuscript and transferred them to small portraits worn in lockets. Though the form was developed in England by foreign artists, mostly Flemish like Lucas Horenbout, the somewhat undistinguished founder of the tradition, by the late 16th century natives such as Nicolas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver produced the finest work, even as the best producers of larger portraits in oil were still foreigners. The portrait miniature had spread all over Europe by the 18th century.

The portraiture of Elizabeth I was carefully controlled and developed into an elaborate and wholly un-realist iconic style, that has succeeded in creating enduring images. The many portraits drove the evolution of English royal portraits in the Early Modern period. Even the earliest portraits of Elizabeth I contain symbolic objects such as roses and prayer books that would have carried meaning to viewers of her day. Later portraits of Elizabeth layer the iconography of empire—globes, crowns, swords and columns—and representations of virginity and purity—such as moons and pearls—with classical allusions to present a complex "story" that conveyed to Elizabethan era viewers the majesty and significance of their Virgin Queen. The Armada Portrait is an allegorical panel painting depicting the queen surrounded by symbols of empire against a backdrop representing the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Music

English Renaissance music kept in touch with continental developments far more than visual art, and managed to survive the Reformation relatively successfully, though William Byrd (c.1539/40 or 1543 – 1623) and other major figures were Catholic. The Elizabethan madrigal was distinct from, but related to, the Italian tradition. Thomas Tallis, (c. 1505 –1585 Thomas Morley (1557 or 1558 – 1602)), and John Dowland (1563 – 1626) were other leading English composers.

The key composers from the early Renaissance era also wrote in a late Medieval style, and as such, they are transitional figures. Leonel Power (c. 1370s or 1380s–1445) was an English composer of the late medieval and early Renaissance music eras. Along with John Dunstaple, he was one of the major figures in English music in the early 15th century. Power is the composer best represented in the Old Hall Manuscript. Power was one of the first composers to set separate movements of the ordinary of the mass which were thematically unified and intended for contiguous performance. The Old Hall Manuscript contains his mass based on the Marian antiphon, Alma Redemptoris Mater, in which the antiphon is stated literally in the tenor voice in each movement, without melodic ornaments. This is the only cyclic setting of the mass ordinary which can be attributed to him. He wrote mass cycles, fragments, and single movements and a variety of other sacred works.

John Dunstaple (or Dunstable) (c. 1390–1453) was an English composer of polyphonic music of the late medieval era and early Renaissance periods. He was one of the most famous composers active in the early 15th century, a near-contemporary of Power, and was widely influential, not only in England but on the continent, especially in the developing style of the Burgundian School. Dunstaple's influence on the continent's musical vocabulary was enormous, particularly considering the relative paucity of his (attributable) works. He was recognized for possessing something never heard before in music of the Burgundian School: la contenance angloise ("the English countenance"), a term used by the poet Martin le Franc in his Le Champion des Dames.

The colossal polychoral productions of the Venetian School had been anticipated in the works of Thomas Tallis, and the Palestrina style from the Roman School had already been absorbed prior to the publication of Musica transalpina, in the music of masters such as William Byrd.

The Italian and English Renaissances were similar in sharing a specific musical aesthetic. In the late 16th century Italy was the musical center of Europe, and one of the principal forms which emerged from that singular explosion of musical creativity was the madrigal. In 1588, Nicholas Yonge published in England the Musica transalpina—a collection of Italian madrigals that had been Anglicized—an event which began a vogue of madrigal in England which was almost unmatched in the Renaissance in being an instantaneous adoption of an idea, from another country, adapted to local aesthetics. English poetry was exactly at the right stage of development for this transplantation to occur, since forms such as the sonnet were uniquely adapted to setting as madrigals; indeed, the sonnet was already well developed in Italy. Composers such as Thomas Morley, the only contemporary composer to set Shakespeare, and whose work survives, published collections of their own, roughly in the Italian manner but yet with a unique Englishness; interest in the compositions of the English Madrigal School has enjoyed a considerable revival in recent decades.

Architecture

Despite some buildings in a partly Renaissance style from the reign of Henry VIII (1491 – 1547), notably Hampton Court Palace (begun in 1515), the vanished Nonsuch Palace, Sutton Place and Layer Marney Tower, and the building of Soulton Hall under Queen Mary I, it was not until dawning of Elizabethan architecture that a true Renaissance style became widespread.

The wool trade, which had carried the economic life of England in the late medieval period, was no longer as prosperous as it had been and there was less disposable wealth for architectural projects. Under Elizabeth, farming was encouraged resulting in a recovery that put a vast amount of wealth into the hands of a large number of people. Elizabeth built no new palaces, instead encouraging her courtiers to build extravagantly and house her on her summer progresses. A large number of small houses were built, and at the same time many country mansions were constructed. Many of the earlier medieval or Tudor manors were remodelled and modernised during Elizabeth's reign. Civic and institutional buildings were also becoming increasingly common.

The most famous buildings, of a type called the prodigy house, are large show houses constructed for courtiers, and characterised by lavish use of glass, as at "Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall", Wollaton Hall, Montacute House, Hatfield House and Burghley House, the style continuing into the early 17th century before developing into Jacobean architecture. Lesser, but still large, houses like Little Moreton Hall continued to be constructed and expanded in essentially medieval half-timbered styles until the late 16th century. Church architecture essentially continued in the late medieval Perpendicular Gothic style until the Reformation, and then stopped almost completely, although church monuments, screens and other fittings often had classical styles from about the mid-century. The few new church buildings post-Reformation were usually still Gothic in style, as in Langley Chapel of 1601.

It was also at this time that the long gallery became popular in English manor houses, often displaying painting collections and decorated ceilings. This was apparently mainly used for walking in, and a growing range of parlours and withdrawing rooms supplemented the main living room for the family, the great chamber. The great hall was now mostly used by the servants, and as an impressive point of entry to the house.

Major English Renaissance authors

Major literary figures in the English Renaissance include:

- Francis Bacon

- Francis Beaumont

- Thomas Campion

- George Chapman

- Francis Hubert

- Thomas Dekker

- John Donne

- John Fletcher

- John Ford

- John Milton

- Ben Jonson

- Thomas Kyd

- Christopher Marlowe

- Philip Massinger

- Thomas Middleton

- Thomas More

- Thomas Nashe

- William Rowley

- William Shakespeare

- James Shirley

- Philip Sidney

- Edmund Spenser

- William Tyndale

- John Webster

- Thomas Wyatt