The tools of monetary policy varies from central bank to central bank, depending on the country's stage of development, institutional structure, tradition and political system. Interest rate targeting is generally the primary tool, being obtained either directly via administratively changing the central bank's own interest rates or indirectly via open market operations. Interest rates affect general economic activity and consequently employment and inflation via a number of different channels, known collectively as the monetary transmission mechanism, and are also an important determinant of the exchange rate. Other policy tools include communication strategies like forward guidance and in some countries the setting of reserve requirements. Monetary policy is often referred to as being either expansionary (stimulating economic activity and consequently employment and inflation) or contractionary (dampening economic activity, hence decreasing employment and inflation).

Monetary policy affects the economy through financial channels like interest rates, exchange rates and prices of financial assets. This is in contrast to fiscal policy, which relies on changes in taxation and government spending as methods for a government to manage business cycle phenomena such as recessions. In developed countries, monetary policy is generally formed separately from fiscal policy, modern central banks in developed economies being independent of direct government control and directives.

How best to conduct monetary policy is an active and debated research area, drawing on fields like monetary economics as well as other subfields within macroeconomics.

History

Issuing coins and paper money

Monetary policy has evolved over the centuries, along with the development of a money economy. Historians, economists, anthropologists and numismatics do not agree on the origins of money. In the West the common point of view is that coins were first used in ancient Lydia in the 8th century BCE, whereas some date the origins to ancient China. The earliest predecessors to monetary policy seem to be those of debasement, where the government would melt coins down and mix them with cheaper metals. The practice was widespread in the late Roman Empire, but reached its perfection in western Europe in the late Middle Ages.

For many centuries there were only two forms of monetary policy: altering coinage or the printing of paper money. Interest rates, while now thought of as part of monetary authority, were not generally coordinated with the other forms of monetary policy during this time. Monetary policy was considered as an executive decision, and was generally implemented by the authority with seigniorage (the power to coin). With the advent of larger trading networks came the ability to define the currency value in terms of gold or silver, and the price of the local currency in terms of foreign currencies. This official price could be enforced by law, even if it varied from the market price.

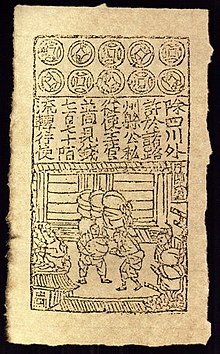

Paper money originated from promissory notes termed "jiaozi" in 7th century China. Jiaozi did not replace metallic currency, and were used alongside the copper coins. The succeeding Yuan Dynasty was the first government to use paper currency as the predominant circulating medium. In the later course of the dynasty, facing massive shortages of specie to fund war and maintain their rule, they began printing paper money without restrictions, resulting in hyperinflation.

Central banks and the gold standard

With the creation of the Bank of England in 1694, which was granted the authority to print notes backed by gold, the idea of monetary policy as independent of executive action began to be established. The purpose of monetary policy was to maintain the value of the coinage, print notes which would trade at par to specie, and prevent coins from leaving circulation. During the period 1870–1920, the industrialized nations established central banking systems, with one of the last being the Federal Reserve in 1913. By this time the role of the central bank as the "lender of last resort" was established. It was also increasingly understood that interest rates had an effect on the entire economy, in no small part because of appreciation for the marginal revolution in economics, which demonstrated that people would change their decisions based on changes in their opportunity costs.

The establishment of national banks by industrializing nations was associated then with the desire to maintain the currency's relationship to the gold standard, and to trade in a narrow currency band with other gold-backed currencies. To accomplish this end, central banks as part of the gold standard began setting the interest rates that they charged both their own borrowers and other banks which required money for liquidity. The maintenance of a gold standard required almost monthly adjustments of interest rates.

The gold standard is a system by which the price of the national currency is fixed vis-a-vis the value of gold, and is kept constant by the government's promise to buy or sell gold at a fixed price in terms of the base currency. The gold standard might be regarded as a special case of "fixed exchange rate" policy, or as a special type of commodity price level targeting. However, the policies required to maintain the gold standard might be harmful to employment and general economic activity and probably exacerbated the Great Depression in the 1930s in many countries, leading eventually to the demise of the gold standards and efforts to create a more adequate monetary framework internationally after World War II. Nowadays the gold standard is no longer used by any country.

Fixed exchange rates prevailing

In 1944, the Bretton Woods system was established, which created the International Monetary Fund and introduced a fixed exchange rate system linking the currencies of most industrialized nations to the US dollar, which as the only currency in the system would be directly convertible to gold. During the following decades the system secured stable exchange rates internationally, but the system broke down during the 1970s when the dollar increasingly came to be viewed as overvalued. In 1971, the dollar's convertibility into gold was suspended. Attempts to revive the fixed exchange rates failed, and by 1973 the major currencies began to float against each other. In Europe, various attempts were made to establish a regional fixed exchange rate system via the European Monetary System, leading eventually to the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union and the introduction of the currency euro.

Money supply targets

Monetarist economists long contended that the money-supply growth could affect the macroeconomy. These included Milton Friedman who early in his career advocated that government budget deficits during recessions be financed in equal amount by money creation to help to stimulate aggregate demand for production. Later he advocated simply increasing the monetary supply at a low, constant rate, as the best way of maintaining low inflation and stable production growth. During the 1970s inflation rose in many countries caused by the 1970s energy crisis, and several central banks turned to a money supply target in an attempt to reduce inflation. However, when U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker tried this policy, starting in October 1979, it was found to be impractical, because of the unstable relationship between monetary aggregates and other macroeconomic variables, and similar results prevailed in other countries. Even Milton Friedman later acknowledged that direct money supplying was less successful than he had hoped.

Inflation targeting

In 1990, New Zealand as the first country ever adopted an official inflation target as the basis of its monetary policy. The idea is that the central bank tries to adjust interest rates in order to steer the country's inflation rate towards the official target instead of following indirect objectives like exchange rate stability or money supply growth, the purpose of which is normally also ultimately to obtain low and stable inflation. The strategy was generally considered to work well, and central banks in most developed countries have over the years adapted a similar strategy.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 sparked controversy over the use and flexibility of the inflation targeting employed. Many economists argued that the actual inflation targets decided upon were set too low by many monetary regimes. During the crisis, many inflation-anchoring countries reached the lower bound of zero rates, resulting in inflation rates decreasing to almost zero or even deflation.

As of 2023, the central banks of all G7 member countries can be said to follow an inflation target, including the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve, who have adopted the main elements of inflation targeting without officially calling themselves inflation targeters. In emerging countries fixed exchange rate regimes are still the most common monetary policy.

-

The Bank of Finland, in Helsinki, established in 1812.

-

The headquarters of the Bank for International Settlements, in Basel (Switzerland).

-

The Reserve Bank of India (established in 1935) Headquarters in Mumbai.

-

The Central Bank of Brazil (established in 1964) in Brasília.

-

The Bank of Spain (established in 1782) in Madrid.

Monetary policy instruments

The instruments available to central banks for conducting monetary policy vary from country to country, depending on the country's stage of development, institutional structure and political system. The main monetary policy instruments available to central banks are interest rate policy, i.e. setting (administered) interest rates directly, open market operations, forward guidance and other communication activities, bank reserve requirements, and re-lending and re-discount (including using the term repurchase market. While capital adequacy is important, it is defined and regulated by the Bank for International Settlements, and central banks in practice generally do not apply stricter rules.

Expansionary policy occurs when a monetary authority uses its instruments to stimulate the economy. An expansionary policy decreases short-term interest rates, affecting broader financial conditions to encourage spending on goods and services, in turn leading to increased employment. By affecting the exchange rate, it may also stimulate net export. Contractionary policy works in the opposite direction: Increasing interest rates will depress borrowing and spending by consumers and businesses, dampening inflationary pressure in the economy together with employment.

Key interest rates

For most central banks in advanced economies, their main monetary policy instrument is a short-term interest rate. For monetary policy frameworks operating under an exchange rate anchor, adjusting interest rates are, together with direct intervention in the foreign exchange market (i.e. open market operations), important tools to maintain the desired exchange rate. For central banks targeting inflation directly, adjusting interest rates are crucial for the monetary transmission mechanism which ultimately affects inflation. Changes in the central banks' policy rates normally affect the interest rates that banks and other lenders charge on loans to firms and households, which will in turn impact private investment and consumption. Interest rate changes also affect asset prices like stock prices and house prices, which again influence households' consumption decisions through a wealth effect. Additionally, international interest rate differentials affect exchange rates and consequently US exports and imports. Consumption, investment and net exports are all important components of aggegate demand. Stimulating or suppressing the overall demand for goods and services in the economy will tend to increase respectively diminish inflation.

The concrete implementation mechanism used to adjust short-term interest rates differs from central bank to central bank. The "policy rate" itself, i.e. the main interest rate which the central bank uses to communicate its policy, may be either an administered rate (i.e. set directly by the central bank) or a market interest rate which the central bank influences only indirectly. By setting administered rates that commercial banks and possibly other financial institutions will receive for their deposits in the central bank, respectively pay for loans from the central bank, the central monetary authority can create a band (or "corridor") within which market interbank short-term interest rates will typically move. Depending on the specific details, the resulting specific market interest rate may either be created by open market operations by the central bank (a so-called "corridor system") or in practice equal the administered rate (a "floor system", practised by the Federal Reserve among others).

As an example of how this functions, the Bank of Canada sets a target overnight rate, and a band of plus or minus 0.25%. Qualified banks borrow from each other within this band, but never above or below, because the central bank will always lend to them at the top of the band, and take deposits at the bottom of the band; in principle, the capacity to borrow and lend at the extremes of the band are unlimited.

The target rates are generally short-term rates. The actual rate that borrowers and lenders receive on the market will depend on (perceived) credit risk, maturity and other factors. For example, a central bank might set a target rate for overnight lending of 4.5%, but rates for (equivalent risk) five-year bonds might be 5%, 4.75%, or, in cases of inverted yield curves, even below the short-term rate.

Many central banks have one primary "headline" rate that is quoted as the "central bank rate". In practice, they will have other tools and rates that are used, but only one that is rigorously targeted and enforced. A typical central bank consequently has several interest rates or monetary policy tools it can use to influence markets.

- Marginal lending rate – a fixed rate for institutions to borrow money from the central bank. (In the USA this is called the discount rate).

- Main refinancing rate – the publicly visible interest rate the central bank announces. It is also known as minimum bid rate and serves as a bidding floor for refinancing loans. (In the USA this is called the federal funds rate).

- Deposit rate, generally consisting of interest on reserves – the rates parties receive for deposits at the central bank.

Open market operations

Through open market operations, a central bank may influence the level of interest rates, the exchange rate and/or the money supply in an economy. Open market operations can influence interest rates by expanding or contracting the monetary base, which consists of currency in circulation and banks' reserves on deposit at the central bank. Each time a central bank buys securities (such as a government bond or treasury bill), it in effect creates money. The central bank exchanges money for the security, increasing the monetary base while lowering the supply of the specific security. Conversely, selling of securities by the central bank reduces the monetary base.

Open market operations usually take the form of:

- Buying or selling securities ("direct operations").

- Temporary lending of money for collateral securities ("Reverse Operations" or "repurchase operations", otherwise known as the "repo" market). These operations are carried out on a regular basis, where fixed maturity loans (of one week and one month for the ECB) are auctioned off.

- Foreign exchange operations such as foreign exchange swaps.

Forward guidance

Forward guidance is a communication practice whereby the central bank announces its forecasts and future intentions to influence market expectations of future levels of interest rates. As expectations formation are an important ingredient in actual inflation changes, credible communication is important for modern central banks.

Reserve requirements

Historically, bank reserves have formed only a small fraction of deposits, a system called fractional-reserve banking. Banks would hold only a small percentage of their assets in the form of cash reserves as insurance against bank runs. Over time this process has been regulated and insured by central banks. Such legal reserve requirements were introduced in the 19th century as an attempt to reduce the risk of banks overextending themselves and suffering from bank runs, as this could lead to knock-on effects on other overextended banks.

A number of central banks have since abolished their reserve requirements over the last few decades, beginning with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1985 and continuing with the Federal Reserve in 2020. For the respective banking systems, bank capital requirements provide a check on the growth of the money supply.

The People's Bank of China retains (and uses) more powers over reserves because the yuan that it manages is a non-convertible currency.

Loan activity by banks plays a fundamental role in determining the money supply. The central-bank money after aggregate settlement – "final money" – can take only one of two forms:

- physical cash, which is rarely used in wholesale financial markets,

- central-bank money which is rarely used by the people

The currency component of the money supply is far smaller than the deposit component. Currency, bank reserves and institutional loan agreements together make up the monetary base, called M1, M2 and M3. The Federal Reserve Bank stopped publishing M3 and counting it as part of the money supply in 2006.

Credit guidance

Central banks can directly or indirectly influence the allocation of bank lending in certain sectors of the economy by applying quotas, limits or differentiated interest rates. This allows the central bank to control both the quantity of lending and its allocation towards certain strategic sectors of the economy, for example to support the national industrial policy, or to environmental investment such as housing renovation.

The Bank of Japan used to apply such policy ("window guidance") between 1962 and 1991. The Banque de France also widely used credit guidance during the post-war period of 1948 until 1973 .

The European Central Bank's ongoing TLTROs operations can also be described as form of credit guidance insofar as the level of interest rate ultimately paid by banks is differentiated according to the volume of lending made by commercial banks at the end of the maintenance period. If commercial banks achieve a certain lending performance threshold, they get a discount interest rate, that is lower than the standard key interest rate. For this reason, some economists have described the TLTROs as a "dual interest rates" policy.

China is also applying a form of dual rate policy.

Exchange requirements

To influence the money supply, some central banks may require that some or all foreign exchange receipts (generally from exports) be exchanged for the local currency. The rate that is used to purchase local currency may be market-based or arbitrarily set by the bank. This tool is generally used in countries with non-convertible currencies or partially convertible currencies. The recipient of the local currency may be allowed to freely dispose of the funds, required to hold the funds with the central bank for some period of time, or allowed to use the funds subject to certain restrictions. In other cases, the ability to hold or use the foreign exchange may be otherwise limited.

In this method, money supply is increased by the central bank when it purchases the foreign currency by issuing (selling) the local currency. The central bank may subsequently reduce the money supply by various means, including selling bonds or foreign exchange interventions.

Collateral policy

In some countries, central banks may have other tools that work indirectly to limit lending practices and otherwise restrict or regulate capital markets. For example, a central bank may regulate margin lending, whereby individuals or companies may borrow against pledged securities. The margin requirement establishes a minimum ratio of the value of the securities to the amount borrowed.

Central banks often have requirements for the quality of assets that may be held by financial institutions; these requirements may act as a limit on the amount of risk and leverage created by the financial system. These requirements may be direct, such as requiring certain assets to bear certain minimum credit ratings, or indirect, by the central bank lending to counter-parties only when security of a certain quality is pledged as collateral.

Unconventional monetary policy at the zero bound

Other forms of monetary policy, particularly used when interest rates are at or near 0% and there are concerns about deflation or deflation is occurring, are referred to as unconventional monetary policy. These include credit easing, quantitative easing, forward guidance, and signalling. In credit easing, a central bank purchases private sector assets to improve liquidity and improve access to credit. Signaling can be used to lower market expectations for lower interest rates in the future. For example, during the credit crisis of 2008, the US Federal Reserve indicated rates would be low for an "extended period", and the Bank of Canada made a "conditional commitment" to keep rates at the lower bound of 25 basis points (0.25%) until the end of the second quarter of 2010.

Helicopter money

Further similar monetary policy proposals include the idea of helicopter money whereby central banks would create money without assets as counterpart in their balance sheet. The money created could be distributed directly to the population as a citizen's dividend. Virtues of such money shocks include the decrease of household risk aversion and the increase in demand, boosting both inflation and the output gap. This option has been increasingly discussed since March 2016 after the ECB's president Mario Draghi said he found the concept "very interesting". The idea was also promoted by prominent former central bankers Stanley Fischer and Philipp Hildebrand in a paper published by BlackRock, and in France by economists Philippe Martin and Xavier Ragot from the French Council for Economic Analysis, a think tank attached to the Prime minister's office.

Some have envisaged the use of what Milton Friedman once called "helicopter money" whereby the central bank would make direct transfers to citizens in order to lift inflation up to the central bank's intended target. Such policy option could be particularly effective at the zero lower bound.

Nominal anchors

Central banks typically use a nominal anchor to pin down expectations of private agents about the nominal price level or its path or about what the central bank might do with respect to achieving that path. A nominal anchor is a variable that is thought to bear a stable relationship to the price level or the rate of inflation over some period of time. The adoption of a nominal anchor is intended to stabilize inflation expectations, which may, in turn, help stabilize actual inflation. Nominal variables historically used as anchors include the gold standard, exchange rate targets, money supply targets, and since the 1990s direct official inflation targets. In addition, economic researchers have proposed variants or alternatives like price level targeting (some times described as an inflation target with a memory) or nominal income targeting.

| Monetary Policy | Target Market Variable | Long Term Objective | Popularity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation Targeting | Interest rate on overnight debt | Low and stable inflation | Usual regime in developed countries today |

| Fixed Exchange Rate | The spot price of the currency | Usually low and stable inflation | Abandoned in most developed economies, common in emerging economies |

| Money supply targeting | The growth in money supply | Low and stable inflation | Influential in the 1980s, today official regime in some developing countries |

| Gold Standard | The spot price of gold | Low inflation as measured by the gold price | Used historically, but completely abandoned today |

| Price Level Targeting | Interest rate on overnight debt | Low and stable inflation | A hypothetical regime, recommended by some academic economists |

| Nominal income target | Nominal GDP | Stable nominal GDP growth | A hypothetical regime, recommended by some academic economists |

| Mixed Policy | Usually interest rates | Various | A prominent example is the US |

Empirically, some researchers suggest that central banks' policies can be described by a simple method called the Taylor rule, according to which central banks adjust their policy interest rate in response to changes in the inflation rate and the output gap. The rule was proposed by John B. Taylor of Stanford University.

Inflation targeting

Under this policy approach, the official target is to keep inflation, under a particular definition such as the Consumer Price Index, within a desired range. Thus, while other monetary regimes usually also have as their ultimate goal to control inflation, they go about it in an indirect way, whereas the inflation targeting employs a more direct approach.

The inflation target is achieved through periodic adjustments to the central bank interest rate target. In addition, clear communication to the public about the central bank's actions and future expectations are an essential part of the strategy, in itself influencing inflation expectations which are considered crucial for actual inflation developments.

Typically the duration that the interest rate target is kept constant will vary between months and years. This interest rate target is usually reviewed on a monthly or quarterly basis by a policy committee. Changes to the interest rate target are made in response to various market indicators in an attempt to forecast economic trends and in so doing keep the market on track towards achieving the defined inflation target.

The inflation targeting approach to monetary policy approach was pioneered in New Zealand. Since 1990, an increasing number of countries have switched to inflation targeting as its monetary policy framework. It is used in, among other countries, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Iceland, India, Philippines, Poland, Sweden, South Africa, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. In 2022, the International Monetary Fund registered that 45 economies used inflation targeting as their monetary policy framework. In addition, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank are generally considered to follow a strategy very close to inflation targeting, even though they do not officially label themselves as inflation targeters. Inflation targeting thus has become the world’s dominant monetary policy framework. However, critics contend that there are unintended consequences to this approach such as fueling the increase in housing prices and contributing to wealth inequalities by supporting higher equity values.

Fixed exchange rate targeting

This policy is based on maintaining a fixed exchange rate with a foreign currency. There are varying degrees of fixed exchange rates, which can be ranked in relation to how rigid the fixed exchange rate is with the anchor nation.

Under a system of fiat fixed rates, the local government or monetary authority declares a fixed exchange rate but does not actively buy or sell currency to maintain the rate. Instead, the rate is enforced by non-convertibility measures (e.g. capital controls, import/export licenses, etc.). In this case there is a black market exchange rate where the currency trades at its market/unofficial rate.

Under a system of fixed-convertibility, currency is bought and sold by the central bank or monetary authority on a daily basis to achieve the target exchange rate. This target rate may be a fixed level or a fixed band within which the exchange rate may fluctuate until the monetary authority intervenes to buy or sell as necessary to maintain the exchange rate within the band. (In this case, the fixed exchange rate with a fixed level can be seen as a special case of the fixed exchange rate with bands where the bands are set to zero.)

Under a system of fixed exchange rates maintained by a currency board every unit of local currency must be backed by a unit of foreign currency (correcting for the exchange rate). This ensures that the local monetary base does not inflate without being backed by hard currency and eliminates any worries about a run on the local currency by those wishing to convert the local currency to the hard (anchor) currency.

Under dollarization, foreign currency (usually the US dollar, hence the term "dollarization") is used freely as the medium of exchange either exclusively or in parallel with local currency. This outcome can come about because the local population has lost all faith in the local currency, or it may also be a policy of the government (usually to rein in inflation and import credible monetary policy).

Theoretically, using relative purchasing power parity (PPP), the rate of depreciation of the home country's currency must equal the inflation differential:

- rate of depreciation = home inflation rate – foreign inflation rate,

which implies that

- home inflation rate = foreign inflation rate + rate of depreciation.

The anchor variable is the rate of depreciation. Therefore, the rate of inflation at home must equal the rate of inflation in the foreign country plus the rate of depreciation of the exchange rate of the home country currency, relative to the other.

With a strict fixed exchange rate or a peg, the rate of depreciation of the exchange rate is set equal to zero. In the case of a crawling peg, the rate of depreciation is set equal to a constant. With a limited flexible band, the rate of depreciation is allowed to fluctuate within a given range.

By fixing the rate of depreciation, PPP theory concludes that the home country's inflation rate must depend on the foreign country's.

Countries may decide to use a fixed exchange rate monetary regime in order to take advantage of price stability and control inflation. In practice, more than half of nations’ monetary regimes use fixed exchange rate anchoring. The great majority of these are emerging economies, Denmark being the only OECD member in 2022 maintaining an exchange rate anchor according to the IMF.

These policies often abdicate monetary policy to the foreign monetary authority or government as monetary policy in the pegging nation must align with monetary policy in the anchor nation to maintain the exchange rate. The degree to which local monetary policy becomes dependent on the anchor nation depends on factors such as capital mobility, openness, credit channels and other economic factors.

Money supply targeting

In the 1980s, several countries used an approach based on a constant growth in the money supply. This approach was refined to include different classes of money and credit (M0, M1 etc.) The approach was influenced by the theoretical school of thought called monetarism. In the US this approach to monetary policy was discontinued with the selection of Alan Greenspan as Fed Chairman.

Central banks might choose to set a money supply growth target as a nominal anchor to keep prices stable in the long term. The quantity theory is a long run model, which links price levels to money supply and demand. Using this equation, we can rearrange to see the following:

- π = μ − g,

where π is the inflation rate, μ is the money supply growth rate and g is the real output growth rate. This equation suggests that controlling the money supply's growth rate can ultimately lead to price stability in the long run. To use this nominal anchor, a central bank would need to set μ equal to a constant and commit to maintaining this target. While monetary policy typically focuses on a price signal of one form or another, this approach is focused on monetary quantities.

However, targeting the money supply growth rate was not a success in practice because the relationship between inflation, economic activity, and measures of money growth turned out to be unstable. Consequently, the importance of the money supply as a guide for the conduct of monetary policy has diminished over time, and after the 1980s central banks have shifted away from policies that focus on money supply targeting. Today, it is widely considered a weak policy, because it is not stably related to the growth of real output. As a result, a higher output growth rate will result in a too low level of inflation. A low output growth rate will result in inflation that would be higher than the desired level.

In 2022, the International Monetary Fund registered that 25 economies, all of them emerging economies, used some monetary aggregate target as their monetary policy framework.

Nominal income/NGDP targeting

Related to money targeting, nominal income targeting (also called Nominal GDP or NGDP targeting), originally proposed by James Meade (1978) and James Tobin (1980), was advocated by Scott Sumner and reinforced by the market monetarist school of thought.

So far, no central banks have implemented this monetary policy. However, various academic studies indicate that such a monetary policy targeting would better match central bank losses and welfare optimizing monetary policy compared to more standard monetary policy targeting.

Price level targeting

Price level targeting is a monetary policy that is similar to inflation targeting except that CPI growth in one year over or under the long term price level target is offset in subsequent years such that a targeted price-level trend is reached over time, e.g. five years, giving more certainty about future price increases to consumers. Under inflation targeting what happened in the immediate past years is not taken into account or adjusted for in the current and future years.

Nominal anchors and exchange rate regimes

The different types of policy are also called monetary regimes, in parallel to exchange-rate regimes. A fixed exchange rate is also an exchange-rate regime. The gold standard results in a relatively fixed regime towards the currency of other countries following a gold standard and a floating regime towards those that are not. Targeting inflation, the price level or other monetary aggregates implies floating the exchange rate.

| Type of Nominal Anchor | Compatible Exchange Rate Regimes |

|---|---|

| Exchange Rate Target | Currency Union/Countries without own currency, Pegs/Bands/Crawls, Managed Floating |

| Money Supply Target | Managed Floating, Freely Floating |

| Inflation Target (+ Interest Rate Policy) | Managed Floating, Freely Floating |

Credibility

The short-term effects of monetary policy can be influenced by the degree to which announcements of new policy are deemed credible. In particular, when an anti-inflation policy is announced by a central bank, in the absence of credibility in the eyes of the public inflationary expectations will not drop, and the short-run effect of the announcement and a subsequent sustained anti-inflation policy is likely to be a combination of somewhat lower inflation and higher unemployment (see Phillips curve § NAIRU and rational expectations). But if the policy announcement is deemed credible, inflationary expectations will drop commensurately with the announced policy intent, and inflation is likely to come down more quickly and without so much of a cost in terms of unemployment.

Thus there can be an advantage to having the central bank be independent of the political authority, to shield it from the prospect of political pressure to reverse the direction of the policy. But even with a seemingly independent central bank, a central bank whose hands are not tied to the anti-inflation policy might be deemed as not fully credible; in this case there is an advantage to be had by the central bank being in some way bound to follow through on its policy pronouncements, lending it credibility.

There is very strong consensus among economists that an independent central bank can run a more credible monetary policy, making market expectations more responsive to signals from the central bank.

Contexts

In international economics

Optimal monetary policy in international economics is concerned with the question of how monetary policy should be conducted in interdependent open economies. The classical view holds that international macroeconomic interdependence is only relevant if it affects domestic output gaps and inflation, and monetary policy prescriptions can abstract from openness without harm. This view rests on two implicit assumptions: a high responsiveness of import prices to the exchange rate, i.e. producer currency pricing (PCP), and frictionless international financial markets supporting the efficiency of flexible price allocation. The violation or distortion of these assumptions found in empirical research is the subject of a substantial part of the international optimal monetary policy literature. The policy trade-offs specific to this international perspective are threefold:

First, research suggests only a weak reflection of exchange rate movements in import prices, lending credibility to the opposed theory of local currency pricing (LCP). The consequence is a departure from the classical view in the form of a trade-off between output gaps and misalignments in international relative prices, shifting monetary policy to CPI inflation control and real exchange rate stabilization.

Second, another specificity of international optimal monetary policy is the issue of strategic interactions and competitive devaluations, which is due to cross-border spillovers in quantities and prices. Therein, the national authorities of different countries face incentives to manipulate the terms of trade to increase national welfare in the absence of international policy coordination. Even though the gains of international policy coordination might be small, such gains may become very relevant if balanced against incentives for international noncooperation.

Third, open economies face policy trade-offs if asset market distortions prevent global efficient allocation. Even though the real exchange rate absorbs shocks in current and expected fundamentals, its adjustment does not necessarily result in a desirable allocation and may even exacerbate the misallocation of consumption and employment at both the domestic and global level. This is because, relative to the case of complete markets, both the Phillips curve and the loss function include a welfare-relevant measure of cross-country imbalances. Consequently, this results in domestic goals, e.g. output gaps or inflation, being traded-off against the stabilization of external variables such as the terms of trade or the demand gap. Hence, the optimal monetary policy in this case consists of redressing demand imbalances and/or correcting international relative prices at the cost of some inflation.

Corsetti, Dedola and Leduc (2011) summarize the status quo of research on international monetary policy prescriptions: "Optimal monetary policy thus should target a combination of inward-looking variables such as output gap and inflation, with currency misalignment and cross-country demand misallocation, by leaning against the wind of misaligned exchange rates and international imbalances." This is main factor in country money status.

In developing countries

Developing countries may have problems establishing an effective operating monetary policy. The primary difficulty is that few developing countries have deep markets in government debt. The matter is further complicated by the difficulties in forecasting money demand and fiscal pressure to levy the inflation tax by expanding the base rapidly. In general, the central banks in many developing countries have poor records in managing monetary policy. This is often because the monetary authorities in developing countries are mostly not independent of the government, so good monetary policy takes a backseat to the political desires of the government or is used to pursue other non-monetary goals. For this and other reasons, developing countries that want to establish credible monetary policy may institute a currency board or adopt dollarization. This can avoid interference from the government and may lead to the adoption of monetary policy as carried out in the anchor nation. Recent attempts at liberalizing and reform of financial markets (particularly the recapitalization of banks and other financial institutions in Nigeria and elsewhere) are gradually providing the latitude required to implement monetary policy frameworks by the relevant central banks.

Trends

Transparency

Beginning with New Zealand in 1990, central banks began adopting formal, public inflation targets with the goal of making the outcomes, if not the process, of monetary policy more transparent. In other words, a central bank may have an inflation target of 2% for a given year, and if inflation turns out to be 5%, then the central bank will typically have to submit an explanation. The Bank of England exemplifies both these trends. It became independent of government through the Bank of England Act 1998 and adopted an inflation target of 2.5% RPI, revised to 2% of CPI in 2003. The success of inflation targeting in the United Kingdom has been attributed to the Bank of England's focus on transparency. The Bank of England has been a leader in producing innovative ways of communicating information to the public, especially through its Inflation Report, which have been emulated by many other central banks.

The European Central Bank adopted, in 1998, a definition of price stability within the Eurozone as inflation of under 2% HICP. In 2003, this was revised to inflation below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. Since then, the target of 2% has become common for other major central banks, including the Federal Reserve (since January 2012) and Bank of Japan (since January 2013).

Effect on business cycles

There continues to be some debate about whether monetary policy can (or should) smooth business cycles. A central conjecture of Keynesian economics is that the central bank can stimulate aggregate demand in the short run, because a significant number of prices in the economy are fixed in the short run and firms will produce as many goods and services as are demanded (in the long run, however, money is neutral, as in the neoclassical model). However, some economists from the new classical school contend that central banks cannot affect business cycles.

Behavioral monetary policy

Conventional macroeconomic models assume that all agents in an economy are fully rational. A rational agent has clear preferences, models uncertainty via expected values of variables or functions of variables, and always chooses to perform the action with the optimal expected outcome for itself among all feasible actions – they maximize their utility. Monetary policy analysis and decisions hence traditionally rely on this New Classical approach.

However, as studied by the field of behavioral economics that takes into account the concept of bounded rationality, people often deviate from the way that these neoclassical theories assume. Humans are generally not able to react in a completely rational manner to the world around them – they do not make decisions in the rational way commonly envisioned in standard macroeconomic models. People have time limitations, cognitive biases, care about issues like fairness and equity and follow rules of thumb (heuristics).

This has implications for the conduct of monetary policy. Monetary policy is the final outcome of a complex interaction between monetary institutions, central banker preferences and policy rules, and hence human decision-making plays an important role.[76] It is more and more recognized that the standard rational approach does not provide an optimal foundation for monetary policy actions. These models fail to address important human anomalies and behavioral drivers that explain monetary policy decisions.

An example of a behavioral bias that characterizes the behavior of central bankers is loss aversion: for every monetary policy choice, losses loom larger than gains, and both are evaluated with respect to the status quo. One result of loss aversion is that when gains and losses are symmetric or nearly so, risk aversion may set in. Loss aversion can be found in multiple contexts in monetary policy. The "hard fought" battle against the Great Inflation, for instance, might cause a bias against policies that risk greater inflation. Another common finding in behavioral studies is that individuals regularly offer estimates of their own ability, competence, or judgments that far exceed an objective assessment: they are overconfident. Central bank policymakers may fall victim to overconfidence in managing the macroeconomy in terms of timing, magnitude, and even the qualitative impact of interventions. Overconfidence can result in actions of the central bank that are either "too little" or "too much". When policymakers believe their actions will have larger effects than objective analysis would indicate, this results in too little intervention. Overconfidence can, for instance, cause problems when relying on interest rates to gauge the stance of monetary policy: low rates might mean that policy is easy, but they could also signal a weak economy.

These are examples of how behavioral phenomena may have a substantial influence on monetary policy. Monetary policy analyses should thus account for the fact that policymakers (or central bankers) are individuals and prone to biases and temptations that can sensibly influence their ultimate choices in the setting of macroeconomic and/or interest rate targets.