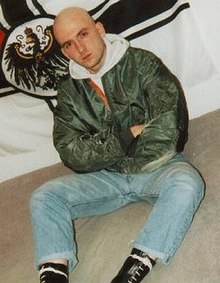

A skinhead or skin is a member of a subculture that originated among working-class youths in London, England, in the 1960s. It soon spread to other parts of the United Kingdom, with a second working-class skinhead movement emerging worldwide in the late 1970s. Motivated by social alienation and working-class solidarity, skinheads are defined by their close-cropped or shaven heads and working-class clothing such as Dr. Martens and steel toe work boots, braces, high rise and varying length straight-leg jeans, and button-down collar shirts, usually slim fitting in check or plain. The movement reached a peak at the end of the 1960s, experienced a revival in the 1980s, and, since then, has endured in multiple contexts worldwide.

The rise to prominence of skinheads came in two waves, with the first wave taking place in the late 1960s in the UK. The first skinheads were working class youths motivated by an expression of alternative values and working class pride, rejecting both the austerity and conservatism of the 1950s-early 1960s and the more middle class or bourgeois hippie movement and peace and love ethos of the mid to late 1960s. Skinheads were instead drawn towards more working class outsider subcultures, incorporating elements of early working class mod fashion and Jamaican music and fashion, especially from Jamaican rude boys. In the earlier stages of the movement, a considerable overlap existed between early skinhead subculture, mod subculture, and the rude boy subculture found among Jamaican British and Jamaican immigrant youth, as these three groups interacted and fraternized with each other within the same working class and poor neighbourhoods in Britain. As skinheads adopted elements of mod subculture and Jamaican British and Jamaican immigrant rude boy subculture, both first and second generation skins were influenced by the rhythms of Jamaican music genres such as ska, rocksteady, and reggae, as well as sometimes African-American soul and rhythm and blues.

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw a revival or second wave of the skinhead subculture, with increasing interaction between its adherents and the emerging punk movement. Oi!, a working class offshoot of punk rock, soon became a vital component of skinhead culture, while the Jamaican genres beloved by first generation skinheads were filtered through punk and new wave in a style known as 2 Tone. Within these new musical movements, the skinhead subculture diversified, and contemporary skinhead fashions ranged from the original clean-cut 1960s mod- and rude boy-influenced styles to less-strict punk-influenced styles.

During the early 1980s, political affiliations grew in significance and split the subculture, demarcating the far-right and far-left strands, although many skins described themselves as apolitical. In Great Britain, the skinhead subculture became associated in the public eye with membership of groups such as the far-right National Front and British Movement. By the 1990s, neo-Nazi skinhead movements existed across all of Europe and North America, but were counterbalanced by the presence of groups such as Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice which sprung up in response. To this day, the skinhead subculture reflects a broad spectrum of political beliefs, even as many continue to embrace it as a largely apolitical working class movement.

History

Origins and first wave

In the late 1950s the post-war economic boom led to an increase in disposable income among many young people. Some of those youths spent that income on new fashions; they wore ripped clothes and would use pieces of material to patch them up as popularised by American soul groups, British R&B bands, certain film actors, and Carnaby Street clothing merchants. These youths became known as mods, a youth subculture noted for its consumerism and devotion to fashion, music, and scooters.

Working class mods chose practical clothing styles that suited their lifestyle and employment circumstances: work boots or army boots, straight-leg jeans or Sta-Prest trousers, button-down shirts and braces. When possible, these working class mods spent their money on suits and other sharp outfits to wear at dancehalls, where they enjoyed soul, ska, and rocksteady music.

Around 1966, a schism developed between the peacock mods (also known as smooth mods), who were less violent and always wore the latest expensive clothes, and the hard mods (also known as gang mods, lemonheads or peanuts), who were identified by their shorter hair and more working class image. Hard mods became commonly known as skinheads by about 1968. Their short hair may have come about for practical reasons, since long hair could be a liability in industrial jobs and streetfights. Skinheads may also have cut their hair short in defiance of the more middle class hippie culture.

In addition to retaining many mod influences, early skinheads were very interested in Jamaican rude boy styles and culture, especially the music: ska, rocksteady, and early reggae (before the tempo slowed down and lyrics became focused on topics like black nationalism and the Rastafari movement).

Skinhead culture became so popular by 1969 that even the rock band Slade temporarily adopted the look as a marketing strategy. The subculture gained wider notice because of a series of violent and sexually explicit novels by Richard Allen, notably Skinhead and Skinhead Escapes. Due to largescale British migration to Perth, Western Australia, many British youths in that city joined skinhead/sharpies gangs in the late 1960s and developed their own Australian style.

By the early 1970s, the skinhead subculture started to fade from popular culture, and some of the original skins dropped into new categories, such as the suedeheads (defined by the ability to manipulate one's hair with a comb), smoothies (often with shoulder-length hairstyles), and bootboys (with mod-length hair; associated with gangs and football hooliganism). Some fashion trends returned to the mod roots, with brogues, loafers, suits, and the slacks-and-sweater look making a comeback.

Second wave

In the late 1970s, the skinhead subculture was revived to a notable extent after the introduction of punk rock. Most of these revivalist skinheads reacted to the commercialism of punk by adopting a look that was in line with the original 1969 skinhead style. This revival included Gary Hodges and Hoxton Tom McCourt (both later of the band the 4-Skins) and Suggs, later of the band Madness. Around this time, some skinheads became affiliated with far right groups such as the National Front and the British Movement. From 1979 onwards, punk-influenced skinheads with shorter hair, higher boots and less emphasis on traditional styles grew in numbers and grabbed media attention, mostly due to football hooliganism. There still remained, however, skinheads who preferred the original mod-inspired styles.

Eventually different interpretations of the skinhead subculture expanded beyond Britain and continental Europe. In the United States, certain segments of the hardcore punk scene embraced skinhead styles and developed their own version of the subculture.

Bill Osgerby has argued that skinhead culture more broadly grows strength from specific economic circumstances. In a BBC interview, he remarked "In the late 70s and early 80s, working class culture was disintegrating through unemployment and inner city decay and there was an attempt to recapture a sense of working class solidarity and identity in the face of a tide of social change."

Germany

By the 1980s street fights regularly broke out in West Germany between skinheads and members of the anti-fascist, and left wing youth movements. German neo-nazis, led among others by Michael Kühnen, sought to expand their ranks with new young members from the burgeoning skinhead scene. On the other side of the Berlin Wall, in East Germany, the skinhead youth movement had developed two different styles: one was more focused on rebellious youth fashion styles while the other camp often dressed in regular clothes and focused more heavily on political activity. These groups were infiltrated by agents of the Stasi and did not last long in East Germany. After a group of skinheads attacked a punk concert at Zion's Church (East Berlin) in 1987, many skinhead leaders fled to West Germany to avoid arrest.

Style

Hair

Most first wave skinheads used a No. 2 or No. 3 grade clip guard cut (short, but not bald). From the late 1970s, male skinheads typically shaved their heads with a No. 2 grade clip or shorter. During that period, side partings were sometimes shaved into the hair. Since the 1980s, some skinheads have clipped their hair with no guard, or even shaved it with a razor. Some skinheads sport sideburns of various styles, usually neatly trimmed.

By the 1970s, most female skins had mod-style haircuts. During the 1980s skinhead revival, many female skinheads had feathercuts (The Chelsea, a fringed bob from the front yet from the back it is an undercut). A feathercut is short on the crown, with fringes at the front, back and sides.

Clothing

Skinheads wore long-sleeve or short-sleeve button-down shirts or polo shirts by brands such as Ben Sherman, Fred Perry, Brutus, Warrior or Jaytex; Lonsdale or Everlast shirts or sweatshirts; Grandfather shirts; V-neck sweaters; sleeveless sweaters (known in the UK as a tank top); cardigan sweaters or T-shirts (plain or with text or designs related to the skinhead subculture). They might wear fitted blazers, Harrington jackets, bomber jackets, denim jackets (usually blue, sometimes splattered with bleach), donkey jackets, Crombie-style overcoats, sheepskin ¾-length coats, short macs, monkey jackets or parkas. Traditional ("hard mod") skinheads sometimes wore suits, often of two-tone ‘Tonik’ fabric (shiny mohair-like material that changes colour in different light and angles), or in a Prince of Wales or houndstooth check pattern.

Many skinheads wore Sta-Prest flat-fronted slacks or other dress trousers; jeans (normally Levi's, Lee or Wrangler); or combat trousers (plain or camouflage). Jeans and slacks were worn deliberately short (either hemmed, rolled or tucked) to show off boots, or to show off bright coloured socks when wearing loafers or brogues. Jeans were often blue, with a parallel leg design, hemmed or with clean and thin rolled cuffs (turn-ups), and were sometimes splattered with bleach to resemble camouflage trousers (a style popular among Oi! skinheads).

Many traditionalist skinheads wore braces (suspenders), in various colours, usually no more than 1" in width, clipped to the trouser waistband. In some areas, braces much wider than that may identify a skinhead as either unfashionable or as a white power skinhead. Traditionally, braces were worn up in an X shape at the back, but some Oi!-oriented skinheads wore their braces hanging down. Patterned braces – often black and white check, or vertical stripes – were sometimes worn by traditional skinheads. In a few cases, the colour of braces or flight jackets were used to signify affiliations. The particular colours chosen have varied regionally, and had totally different meanings in different areas and time periods. Only skinheads from the same area and time period are likely to interpret the colour significations accurately. The practice of using the colour clothing items to indicate affiliations became less common, particularly among traditionalist skinheads, who were more likely to choose their colours simply for fashion.

Hats common among skinheads include: Trilby hats; pork pie hats; flat caps (Scally caps or driver caps), winter woollen hats (without a bobble). Less common have been bowler hats (mostly among suedeheads and those influenced by the film A Clockwork Orange).

Traditionalist skinheads sometimes wore a silk handkerchief in the breast pocket of a Crombie-style overcoat or tonic suit jacket, in some cases fastened with an ornate stud. Some wore pocket flashes instead. These are pieces of silk in contrasting colours, mounted on a piece of cardboard and designed to look like an elaborately folded handkerchief. It was common to choose the colours based on one's favourite football club. Some skinheads wore button badges or sewn-on fabric patches with designs related to affiliations, interests or beliefs. Also popular were woollen or printed rayon scarves in football club colours, worn knotted at the neck, wrist, or hanging from a belt loop at the waist. Silk or faux-silk scarves (especially Tootal brand) with paisley patterns were also sometimes worn. Some suedeheads carried closed umbrellas with sharpened tips, or a handle with a pull-out blade. This led to the nickname brollie boys.

Female skinheads generally wore the same clothing items as men, with addition of skirts, stockings, or dress suits composed of a three-quarter-length jacket and matching short skirt. Some skingirls wore fishnet stockings and mini-skirts, a style introduced during the punk-influenced skinhead revival.

Footwear

Most skinheads wear boots; in the 1960s army surplus or generic workboots, later Dr. Martens boots and shoes. In 1960s Britain, steel-toe boots worn by skinheads and hooligans were called bovver boots; whence skinheads have themselves sometimes been called bovver boys. Skinheads have also been known to wear brogues, loafers or Dr. Martens (or similarly styled) low shoes.

In recent years, other brands of boots, such as Solovair, Tredair Grinders, and gripfast have become popular among skinheads, partly because most Dr. Martens are no longer made in England. Football-style athletic shoes, by brands such as Adidas or Gola, have become popular with many skinheads. Female or child skinheads generally wear the same footwear as men, with the addition of monkey boots. The traditional brand for monkey boots was Grafters, but nowadays they are also made by Dr. Martens and Solovair.

In the early days of the skinhead subculture, some skinheads chose boot lace colours based on the football team they supported. Later, some skinheads (particularly highly political ones) began to use lace colour to indicate beliefs or affiliations. The particular colours chosen have varied regionally, and have had totally different meanings in different areas and time periods. Only skinheads from the same area and time period are likely to interpret the colour significations accurately. This practice has become less common, particularly among traditionalist skinheads, who are more likely to choose their colours simply for fashion purposes.

Suedeheads sometimes wore coloured socks (for example, red or blue rather than black or white).

Music

The skinhead subculture was originally associated with black music genres such as soul, ska, R&B, rocksteady, and early reggae. The link between skinheads and Jamaican music led to the UK popularity of groups such as Desmond Dekker, Derrick Morgan, Laurel Aitken, Symarip and The Pioneers. In the early 1970s, some reggae songs began to feature themes of black nationalism, which many white skinheads could not relate to. This shift in reggae's lyrical themes created some tension between black and white skinheads, who otherwise got along fairly well. Around this time, some suedeheads (an offshoot of the skinhead subculture) started listening to British glam rock bands such as Sweet, Slade and Mott the Hoople.

The most popular music style for late-1970s skinheads was 2 Tone, a fusion of ska, rocksteady, reggae, pop and punk rock. The 2 Tone genre was named after 2 Tone Records, a Coventry record label that featured bands such as The Specials, Madness and The Selecter. Some late-1970s skinheads also liked certain punk rock bands, such as Sham 69 and Menace.

In the late 1970s, after the first wave of punk rock, many skinheads embraced Oi!, a working class punk subgenre. Musically, Oi! combines standard punk with elements of football chants, pub rock and British glam rock. The Oi! scene was partly a response to a sense that many participants in the early punk scene were, in the words of The Business guitarist Steve Kent, "trendy university people using long words, trying to be artistic ... and losing touch". The term Oi! as a musical genre is said to come from the band Cockney Rejects and journalist Garry Bushell, who championed the genre in Sounds magazine. Not exclusively a skinhead genre, many Oi! bands included skins, punks and people who fit into neither category. Notable Oi! bands of the late 1970s and early 1980s include Angelic Upstarts, Blitz, the Business, Last Resort, The Burial, Combat 84 and the 4-Skins.

American Oi! began in the 1980s, with bands such as U.S. Chaos, The Press, Iron Cross, The Bruisers and Anti-Heros. American skinheads created a link between their subculture and hardcore punk music, with bands such as Warzone, Agnostic Front, and Cro-Mags. The Oi! style has also spread to other parts of the world, and remains popular with many skinheads. Many later Oi! bands have combined influences from early American hardcore and 1970s British streetpunk.

Among some skinheads, heavy metal is popular. Bands such as the Canadian act Blasphemy, whose guitarist is black, has been known to popularise and merchandise the phrase "black metal skinheads". As the group's vocalist recounts, "a lot of black metal skinheads from the other side of Canada" would join in on the British Columbian black metal underground. "I remember one guy... who had 'Black Metal Skins' tattooed on his forehead. We didn't hang out with white power skinheads, but there were some Oi skinheads who wanted to hang out with us." National Socialist black metal has an audience among white power skinheads. There was a record label called "Satanic Skinhead Propaganda" that was known to specialize in neo-Nazi black metal and death metal bands. Black metal pioneer and right-wing extremist Varg Vikernes was known to adopt a skinhead look and wear a belt with the SS insignia while serving time in prison for the arson of several stave churches and the murder of Øystein Aarseth.

Although many white power skinheads listened to Oi! music, they developed a separate genre more in line with their politics: Rock Against Communism (RAC). The most notable RAC band was Skrewdriver, which started out as a non-political punk band but evolved into a neo-Nazi band after the first lineup broke up and a new lineup was formed. RAC started out musically similar to Oi! and punk, but has since adopted elements from other genres. White power music that draws inspiration from hardcore punk is sometimes called hatecore.

Racism, anti-racism, and politics

The early skinheads were not necessarily part of any political movement, but as the 1970s progressed, many skinheads became more politically active and acts of racially-motivated skinhead violence began to occur in the United Kingdom. As a result of this change within the skinheads, far right groups such as the National Front and the British Movement saw a rise in the number of white power skinheads among their ranks. By the late 1970s, the mass media, and subsequently the general public, had largely come to view the skinhead subculture as one that promotes racism and neo-Nazism. The white power and neo-Nazi skinhead subculture eventually spread to North America, Europe and other areas of the world. The mainstream media started using the term skinhead in reports of racist violence (regardless of whether the perpetrator was actually a skinhead); this has played a large role in skewing public perceptions about the subculture. Three notable groups that formed in the 1980s and which later became associated with white power skinheads are White Aryan Resistance, Blood and Honour and Hammerskins.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, many skinheads and suedeheads in the United Kingdom rejected both the far left and the far right. This attitude was musically typified by Oi! bands such as Cockney Rejects, The 4-Skins, Toy Dolls, and The Business. Two notable groups of skinheads that spoke out against neo-Nazism and political extremism—and instead spoke out in support of traditional skinhead culture—were the Glasgow Spy Kids in Scotland (who coined the phrase Spirit of '69), and the publishers of the Hard As Nails zine in England.

In the late 1960s, some skinheads in the United Kingdom (including black skinheads) engaged in violence against South Asian immigrants (an act known as Paki bashing in common slang). There had, however, also been anti-racist skinheads since the beginning of the subculture, especially in Scotland and Northern England.

On the far left of the skinhead subculture, redskins and anarchist skinheads take a militant anti-fascist and pro-working class stance. The phrase "all cops are bastards" was popularized among some skinheads by The 4-Skins's 1982 song "A.C.A.B." In the United Kingdom, two groups with significant numbers of leftist skinhead members were Red Action, which started in 1981, and Anti-Fascist Action, which started in 1985. Internationally, the most notable skinhead organization is Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, which formed in the New York City area in 1987 and then spread to other countries.