In economics, competition is a scenario where different economic firms are in contention to obtain goods that are limited by varying the elements of the marketing mix: price, product, promotion and place. In classical economic thought, competition causes commercial firms to develop new products, services and technologies, which would give consumers greater selection and better products. The greater the selection of a good is in the market, the lower prices for the products typically are, compared to what the price would be if there was no competition (monopoly) or little competition (oligopoly).

The level of competition that exists within the market is dependent on a variety of factors both on the firm/ seller side; the number of firms, barriers to entry, information, and availability/ accessibility of resources. The number of buyers within the market also factors into competition with each buyer having a willingness to pay, influencing overall demand for the product in the market.

Competitiveness pertains to the ability and performance of a firm, sub-sector or country to sell and supply goods and services in a given market, in relation to the ability and performance of other firms, sub-sectors or countries in the same market. It involves one company trying to figure out how to take away market share from another company. Competitiveness is derived from the Latin word "competere", which refers to the rivalry that is found between entities in markets and industries. It is used extensively in management discourse concerning national and international economic performance comparisons.

The extent of the competition present within a particular market can be measured by; the number of rivals, their similarity of size, and in particular the smaller the share of industry output possessed by the largest firm, the more vigorous competition is likely to be.

History of economic thought on competition

Early economic research focused on the difference between price and non-price based competition, while modern economic theory has focused on the many-seller limit of general equilibrium.

According to 19th century economist Antoine Augustin Cournot, the definition of competition is the situation in which price does not vary with quantity, or in which the demand curve facing the firm is horizontal.

Firm competition

Empirical observation confirms that resources (capital, labor, technology) and talent tend to concentrate geographically (Easterly and Levine 2002). This result reflects the fact that firms are embedded in inter-firm relationships with networks of suppliers, buyers and even competitors that help them to gain competitive advantages in the sale of its products and services. While arms-length market relationships do provide these benefits, at times there are externalities that arise from linkages among firms in a geographic area or in a specific industry (textiles, leather goods, silicon chips) that cannot be captured or fostered by markets alone. The process of "clusterization", the creation of "value chains", or "industrial districts" are models that highlight the advantages of networks.

Within capitalist economic systems, the drive of enterprises is to maintain and improve their own competitiveness, this practically pertains to business sectors.

Perfect vs imperfect competition

Perfect competition

Neoclassical economic theory places importance in a theoretical market state, in which the firms and market are considered to be in perfect competition. Perfect competition is said to exist when all criteria are met, which is rarely (if ever) observed in the real world. These criteria include; all firms contribute insignificantly to the market, all firms sell an identical product, all firms are price takers, market share has no influence on price, both buyers and sellers have complete or "perfect" information, resources are perfectly mobile and firms can enter or exit the market without cost. Under idealized perfect competition, there are many buyers and sellers within the market and prices reflect the overall supply and demand. Another key feature of a perfectly competitive market is the variation in products being sold by firms. The firms within a perfectly competitive market are small, with no larger firms controlling a significant proportion of market share. These firms sell almost identical products with minimal differences or in-cases perfect substitutes to another firm's product.

The idea of perfectly competitive markets draws in other neoclassical theories of the buyer and seller. The buyer in a perfectly competitive market have identical tastes and preferences with respect to desired product features and characteristics (homogeneous within industries) and also have perfect information on the goods such as price, quality and production. In this type of market, buyers are utility maximizers, in which they are purchasing a product that maximizes their own individual utility that they measure through their preferences. The firm, on the other hand, is aiming to maximize profits acting under the assumption of the criteria for perfect competition.

The firm in a perfectly competitive market will operate in two economic time horizons; the short-run and long-run. In the short-run the firm adjusts its quantity produced according to prices and costs. While in the long run the firm is adjusting its methods of production to ensure they produce at a level where marginal cost equals marginal revenue. In a perfectly competitive market, firms/producers earn zero economic profit in the long run. This is proved by Cournot's system.

Imperfect competition

Imperfectly competitive markets are the realistic markets that exist in the economy. Imperfect competition exist when; buyers might not have the complete information on the products sold, companies sell different products and services, set their own individual prices, fight for market share and are often protected by barriers to entry and exit, making it harder for new firms to challenge them. An important differentiation from perfect competition is, in markets with imperfect competition, individual buyers and sellers have the ability to influence prices and production. Under these circumstances, markets move away from the theory of a perfectly competitive market, as real market often do not meet the assumptions of the theory and this inevitably leads to opportunities to generate more profit, unlike in a perfect competition environment, where firms earn zero economic profit in the long run. These markets are also defined by the presence of monopolies, oligopolies and externalities within the market.

The measure of competition in accordance to the theory of perfect competition can be measured by either; the extent of influence of the firm's output on price (the elasticity of demand), or the relative excess of price over marginal cost.

Types of imperfect competition

Monopoly

Monopoly is the opposite to perfect competition. Where perfect competition is defined by many small firms competition for market share in the economy, Monopolies are where one firm holds the entire market share. Instead of industry or market defining the firms, monopolies are the single firm that defines and dictates the entire market. Monopolies exist where one of more of the criteria fail and make it difficult for new firms to enter the market with minimal costs. Monopoly companies use high barriers to entry to prevent and discourage other firms from entering the market to ensure they continue to be the single supplier within the market. A natural monopoly is a type of monopoly that exists due to the high start-up costs or powerful economies of scale of conducting a business in a specific industry. These types of monopolies arise in industries that require unique raw materials, technology, or similar factors to operate. Monopolies can form through both fair and unfair business tactics. These tactics include; collusion, mergers, acquisitions, and hostile takeovers. Collusion might involve two rival competitors conspiring together to gain an unfair market advantage through coordinated price fixing or increases. Natural monopolies are formed through fair business practices where a firm takes advantage of an industry's high barriers. The high barriers to entry are often due to the significant amount of capital or cash needed to purchase fixed assets, which are physical assets a company needs to operate. Natural monopolies are able to continue to operate as they typically can as they produce and sell at a lower cost to consumers than if there was competition in the market. Monopolies in this case use the resources efficiently in order to provide the product at a lower price. Similar to competitive firms, monopolists produces a quantity at that marginal revenue equals marginal cost. The difference here is that in a monopoly, marginal revenue does not equal to price because as a sole supplier in the market, monopolists have the freedom to set the price at which the buyers are willing to pay for to achieve profit-maximizing quantity.

Oligopoly

Oligopolies are another form of imperfect competition market structures. An oligopoly is when a small number of firms collude, either explicitly or tacitly, to restrict output and/or fix prices, in order to achieve above normal market returns. Oligopolies can be made up of two or more firms. Oligopoly is a market structure that is highly concentrated. Competition is well defined through the Cournot's model because, when there are infinite many firms in the market, the excess of price over marginal cost will approach to zero. A duopoly is a special form of oligopoly where the market is made up of only two firms. Only a few firms dominate, for example, major airline companies like Delta and American Airlines operate with a few close competitors, but there are other smaller airlines that are competing in this industry as well. Similar factors that allow monopolies to exist also facilitate the formation of oligopolies. These include; high barriers to entry, legal privilege; government outsourcing to a few companies to build public infrastructure (e.g. railroads) and access to limited resources, primarily seen with natural resources within a nation. Companies in an oligopoly benefit from price-fixing, setting prices collectively, or under the direction of one firm in the bunch, rather than relying on free-market forces to do so. Oligopolies can form cartels in order to restrict entry of new firms into the market and ensure they hold market share. Governments usually heavily regulate markets that are susceptible to oligopolies to ensure that consumers are not being over charged and competition remains fair within that particular market.

Monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition characterizes an industry in which many firms offer products or services that are similar, but not perfect substitutes. Barriers to entry and exit in a monopolistic competitive industry are low, and the decisions of any one firm do not directly affect those of its competitors. Monopolistic competition exists in-between monopoly and perfect competition, as it combines elements of both market structures. Within monopolistic competition market structures all firms have the same, relatively low degree of market power; they are all price makers, rather than price takers. In the long run, demand is highly elastic, meaning that it is sensitive to price changes. In order to raise their prices, firms must be able to differentiate their products from their competitors in terms of quality, whether real or perceived. In the short run, economic profit is positive, but it approaches zero in the long run. Firms in monopolistic competition tend to advertise heavily because different firms need to distinguish similar products than others. Examples of monopolistic competition include; restaurants, hair salons, clothing, and electronics.

The monopolistic competition market has a relatively large degree of competition and a small degree of monopoly, which is closer to perfect competition, and is much more realistic. It is common in retail, handicraft, and printing industries in big cities. Generally speaking, this market has the following characteristics.

1. There are many manufacturers in the market, and each manufacturer must accept the market price to a certain extent, but each manufacturer can exert a certain degree of influence on the market and not fully accept the market price. In addition, manufacturers cannot collude with each other to control the market. For consumers, the situation is similar. The economic man in such a monopolistic competitive market is the influencer of the market price.

2. Independence Every economic person in the market thinks that they can act independently of each other, independent of each other. A person's decision has little impact on others and is not easy to detect, so it is not necessary to consider other people's confrontational actions.

3. Product differences The products of different manufacturers in the same industry are different from each other, either because of quality difference, or function difference, or insubstantial difference (such as difference in impression caused by packaging, trademark, advertising, etc.), or difference in sales conditions (such as geographical location, Differences in service attitudes and methods cause consumers to be willing to buy products from one company, but not from another). Product differences are the root cause of manufacturers' monopoly, but because the differences between products in the same industry are not so large that products cannot be replaced at all, and a certain degree of mutual substitutability allows manufacturers to compete with each other, so mutual substitution is the source of manufacturer competition. . If you want to accurately state the meaning of product differences, you can say this: at the same price, if a buyer shows a special preference for a certain manufacturer's products, it can be said that the manufacturer's products are different from other manufacturers in the same industry. Products are different.

4. Easy in and out It is easier for manufacturers to enter and exit an industry. This is similar to perfect competition. The scale of the manufacturer is not very large, the capital required is not too much, and the barriers to entering and exiting an industry are relatively easy.

5. Can form product groups Multiple product groups can be formed within the industry, that is, manufacturers producing similar commodities in the industry can form groups. The products of these groups are more different, and the products within the group are less different.

Dominant firms

In several highly concentrated industries, a dominant firm serves a majority of the market. Dominant firms have a market share of 50% to over 90%, with no close rival. Similar to a monopoly market, it uses high entry barrier to prevent other firms from entering the market and competing with them. They have the ability to control pricing, to set systematic discriminatory prices, to influence innovation, and (usually) to earn rates of return well above the competitive rate of return. This is similar to a monopoly, however there are other smaller firms present within the market that make up competition and restrict the ability of the dominant firm to control the entire market and choose their own prices. As there are other smaller firms present in the market, dominant firms must be careful not to raise prices too high as it will induce customers to begin to buy from firms in the fringe of small competitors.

Effective competition

Effective competition is said to exist when there are four firms with market share below 40% and flexible pricing. Low entry barriers, little collusion, and low profit rates. The main goal of effective competition is to give competing firms the incentive to discover more efficient forms of production and to find out what consumers want so they are able to have specific areas to focus on.

Competitive equilibrium

Competitive equilibrium is a concept in which profit-maximizing producers and utility-maximizing consumers in competitive markets with freely determined prices arrive at an equilibrium price. At this equilibrium price, the quantity supplied is equal to the quantity demanded. This implies that a fair deal has been reached between supplier and buyer, in-which all suppliers have been matched with a buyer that is willing to purchase the exact quantity the supplier is looking to sell and therefore, the market is in equilibrium.

The competitive equilibrium has many applications for predicting both the price and total quality in a particular market. It can also be used to estimate the quantity consumed from each individual and the total output of each firm within a market. Furthermore, through the idea of a competitive equilibrium, particular government policies or events can be evaluated and decide whether they move the market towards or away from the competitive equilibrium.

Role in market success

Competition is generally accepted as an essential component of markets, and results from scarcity—there is never enough to satisfy all conceivable human wants—and occurs "when people strive to meet the criteria that are being used to determine who gets what." In offering goods for exchange, buyers competitively bid to purchase specific quantities of specific goods which are available, or might be available if sellers were to choose to offer such goods. Similarly, sellers bid against other sellers in offering goods on the market, competing for the attention and exchange resources of buyers.

The competitive process in a market economy exerts a sort of pressure that tends to move resources to where they are most needed, and to where they can be used most efficiently for the economy as a whole. For the competitive process to work however, it is "important that prices accurately signal costs and benefits." Where externalities occur, or monopolistic or oligopolistic conditions persist, or for the provision of certain goods such as public goods, the pressure of the competitive process is reduced.

In any given market, the power structure will either be in favor of sellers or in favor of buyers. The former case is known as a seller's market; the latter is known as a buyer's market or consumer sovereignty. In either case, the disadvantaged group is known as price-takers and the advantaged group known as price-setters. Price takers must accept the prevailing price and sell their goods at the market price whereas price setters are able to influence market price and enjoy pricing power.

Competition has been shown to be a significant predictor of productivity growth within nation states. Competition bolsters product differentiation as businesses try to innovate and entice consumers to gain a higher market share and increase profit. It helps in improving the processes and productivity as businesses strive to perform better than competitors with limited resources. The Australian economy thrives on competition as it keeps the prices in check.

Historical views

In his 1776 The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith described it as the exercise of allocating productive resources to their most highly valued uses and encouraging efficiency, an explanation that quickly found support among liberal economists opposing the monopolistic practices of mercantilism, the dominant economic philosophy of the time. Smith and other classical economists before Cournot were referring to price and non-price rivalry among producers to sell their goods on best terms by bidding of buyers, not necessarily to a large number of sellers nor to a market in final equilibrium.

Later microeconomic theory distinguished between perfect competition and imperfect competition, concluding that perfect competition is Pareto efficient while imperfect competition is not. Conversely, by Edgeworth's limit theorem, the addition of more firms to an imperfect market will cause the market to tend towards Pareto efficiency. Pareto efficiency, named after the Italian economist and political scientist Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), is an economic state where resources cannot be reallocated to make one individual better off without making at least one individual worse off. It implies that resources are allocated in the most economically efficient manner, however, it does not imply equality or fairness.

Appearance in real markets

Real markets are never perfect. Economists who believe that perfect competition is a useful approximation to real markets classify markets as ranging from close-to-perfect to very imperfect. Examples of close-to-perfect markets typically include share and foreign exchange markets while the real estate market is typically an example of a very imperfect market. In such markets, the theory of the second best proves that, even if one optimality condition in an economic model cannot be satisfied, the next-best solution can be achieved by changing other variables away from otherwise-optimal values.

Time variation

Within competitive markets, markets are often defined by their sub-sectors, such as the "short term" / "long term", "seasonal" / "summer", or "broad" / "remainder" market. For example, in otherwise competitive market economies, a large majority of the commercial exchanges may be competitively determined by long-term contracts and therefore long-term clearing prices. In such a scenario, a "remainder market" is one where prices are determined by the small part of the market that deals with the availability of goods not cleared via long term transactions. For example, in the sugar industry, about 94-95% of the market clearing price is determined by long-term supply and purchase contracts. The balance of the market (and world sugar prices) are determined by the ad hoc demand for the remainder; quoted prices in the "remainder market" can be significantly higher or lower than the long-term market clearing price. Similarly, in the US real estate housing market, appraisal prices can be determined by both short-term or long-term characteristics, depending on short-term supply and demand factors. This can result in large price variations for a property at one location.

Anti-competitive pressures and practices

Competition requires the existing of multiple firms, so it duplicates fixed costs. In a small number of goods and services, the resulting cost structure means that producing enough firms to effect competition may itself be inefficient. These situations are known as natural monopolies and are usually publicly provided or tightly regulated.

International competition also differentially affects sectors of national economies. In order to protect political supporters, governments may introduce protectionist measures such as tariffs to reduce competition.

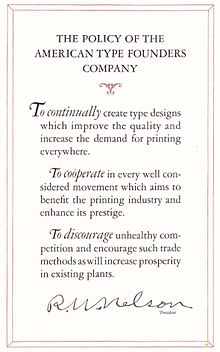

Anti-competitive practices

A practice is anti-competitive if it unfairly distorts free and effective competition in the marketplace. Examples include cartelization and evergreening.

National competition

Economic competition between countries (nations, states) as a political-economic concept emerged in trade and policy discussions in the last decades of the 20th century. Competition theory posits that while protectionist measures may provide short-term remedies to economic problems caused by imports, firms and nations must adapt their production processes in the long term to produce the best products at the lowest price. In this way, even without protectionism, their manufactured goods are able to compete successfully against foreign products both in domestic markets and in foreign markets. Competition emphasizes the use of comparative advantage to decrease trade deficits by exporting larger quantities of goods that a particular nation excels at producing, while simultaneously importing minimal amounts of goods that are relatively difficult or expensive to manufacture. Commercial policy can be used to establish unilaterally and multilaterally negotiated rule of law agreements protecting fair and open global markets. While commercial policy is important to the economic success of nations, competitiveness embodies the need to address all aspects affecting the production of goods that will be successful in the global market, including but not limited to managerial decision making, labor, capital, and transportation costs, reinvestment decisions, the acquisition and availability of human capital, export promotion and financing, and increasing labor productivity.

Competition results from a comprehensive policy that both maintains a favorable global trading environment for producers and domestically encourages firms to work for lower production costs while increasing the quality of output so that they are able to capitalize on favorable trading environments. These incentives include export promotion efforts and export financing—including financing programs that allow small and medium-sized companies to finance the capital costs of exporting goods. In addition, trading on the global scale increases the robustness of American industry by preparing firms to deal with unexpected changes in the domestic and global economic environments, as well as changes within the industry caused by accelerated technological advancements According to economist Michael Porter, "A nation's competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade."

History of competition

Advocates for policies that focus on increasing competition argue that enacting only protectionist measures can cause atrophy of domestic industry by insulating them from global forces. They further argue that protectionism is often a temporary fix to larger, underlying problems: the declining efficiency and quality of domestic manufacturing. American competition advocacy began to gain significant traction in Washington policy debates in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of increasing pressure on the United States Congress to introduce and pass legislation increasing tariffs and quotas in several large import-sensitive industries. High level trade officials, including commissioners at the U.S. International Trade Commission, pointed out the gaps in legislative and legal mechanisms in place to resolve issues of import competition and relief. They advocated policies for the adjustment of American industries and workers impacted by globalization and not simple reliance on protection.

1980s

As global trade expanded after the early 1980s recession, some American industries, such as the steel and automobile sectors, which had long thrived in a large domestic market, were increasingly exposed to foreign competition. Specialization, lower wages, and lower energy costs allowed developing nations entering the global market to export high quantities of low cost goods to the United States. Simultaneously, domestic anti-inflationary measures (e.g. higher interest rates set by the Federal Reserve) led to a 65% increase in the exchange value of the US dollar in the early 1980s. The stronger dollar acted in effect as an equal percent tax on American exports and equal percent subsidy on foreign imports. American producers, particularly manufacturers, struggled to compete both overseas and in the US marketplace, prompting calls for new legislation to protect domestic industries. In addition, the recession of 1979-82 did not exhibit the traits of a typical recessionary cycle of imports, where imports temporarily decline during a downturn and return to normal during recovery. Due to the high dollar exchange rate, importers still found a favorable market in the United States despite the recession. As a result, imports continued to increase in the recessionary period and further increased in the recovery period, leading to an all-time high trade deficit and import penetration rate. The high dollar exchange rate in combination with high interest rates also created an influx of foreign capital flows to the United States and decreased investment opportunities for American businesses and individuals.

The manufacturing sector was most heavily impacted by the high dollar value. In 1984, the manufacturing sector faced import penetration rates of 25%. The "super dollar" resulted in unusually high imports of manufactured goods at suppressed prices. The U.S. steel industry faced a combination of challenges from increasing technology, a sudden collapse of markets due to high interest rates, the displacement of large integrated producers, increasingly uncompetitive cost structure due to increasing wages and reliance on expensive raw materials, and increasing government regulations around environmental costs and taxes. Added to these pressures was the import injury inflicted by low cost, sometimes more efficient foreign producers, whose prices were further suppressed in the American market by the high dollar.

The Trade and Tariff Act of 1984 developed new provisions for adjustment assistance, or assistance for industries that are damaged by a combination of imports and a changing industry environment. It maintained that as a requirement for receiving relief, the steel industry would be required to implement measures to overcome other factors and adjust to a changing market. The act built on the provisions of the Trade Act of 1974 and worked to expand, rather than limit, world trade as a means to improve the American economy. Not only did this act give the President greater authority in giving protections to the steel industry, it also granted the President the authority to liberalize trade with developing economies through Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) while extending the Generalized System of Preferences. The Act also made significant updates to the remedies and processes for settling domestic trade disputes.

The injury caused by imports strengthened by the high dollar value resulted in job loss in the manufacturing sector, lower living standards, which put pressure on Congress and the Reagan Administration to implement protectionist measures. At the same time, these conditions catalyzed a broader debate around the measures necessary to develop domestic resources and to advance US competition. These measures include increasing investment in innovative technology, development of human capital through worker education and training, and reducing costs of energy and other production inputs. Competitiveness is an effort to examine all the forces needed to build up the strength of a nation's industries to compete with imports.

In 1988, the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act was passed. The Act's underlying goal was to bolster America's ability to compete in the world marketplace. It incorporated language on the need to address sources of American competition and to add new provisions for imposing import protection. The Act took into account U.S. import and export policy and proposed to provide industries more effective import relief and new tools to pry open foreign markets for American business. Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 had provided for investigations into industries that had been substantially damaged by imports. These investigations, conducted by the USITC, resulted in a series of recommendations to the President to implement protection for each industry. Protection was only offered to industries where it was found that imports were the most important cause of injury over other sources of injury.

Section 301 of the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 contained provisions for the United States to ensure fair trade by responding to violations of trade agreements and unreasonable or unjustifiable trade-hindering activities by foreign governments. A sub-provision of Section 301 focused on ensuring intellectual property rights by identifying countries that deny protection and enforcement of these rights, and subjecting them to investigations under the broader Section 301 provisions. Expanding U.S. access to foreign markets and shielding domestic markets reflected an increased interest in the broader concept of competition for American producers. The Omnibus amendment, originally introduced by Rep. Dick Gephardt, was signed into effect by President Reagan in 1988 and renewed by President Bill Clinton in 1994 and 1999.990s

While competition policy began to gain traction in the 1980s, in the 1990s it became a concrete consideration in policy making, culminating in President Clinton's economic and trade agendas. The Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Policy expired in 1991; Clinton renewed it in 1994, representing a renewal of focus on a competitiveness-based trade policy.

According to the Competitiveness Policy Council Sub-council on Trade Policy, published in 1993, the main recommendation for the incoming Clinton Administration was to make all aspects of competition a national priority. This recommendation involved many objectives, including using trade policy to create open and fair global markets for US exporters through free trade agreements and macroeconomic policy coordination, creating and executing a comprehensive domestic growth strategy between government agencies, promoting an "export mentality", removing export disincentives, and undertaking export financing and promotion efforts.

The Trade Sub-council also made recommendations to incorporate competition policy into trade policy for maximum effectiveness, stating "trade policy alone cannot ensure US competitiveness". Rather, the sub-council asserted trade policy must be part of an overall strategy demonstrating a commitment at all policy levels to guarantee our future economic prosperity. The Sub-council argued that even if there were open markets and domestic incentives to export, US producers would still not succeed if their goods could not compete against foreign products both globally and domestically.

In 1994, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) became the World Trade Organization (WTO), formally creating a platform to settle unfair trade practice disputes and a global judiciary system to address violations and enforce trade agreements. Creation of the WTO strengthened the international dispute settlement system that had operated in the preceding multilateral GATT mechanism. That year, 1994, also saw the installment of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which opened markets across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

In recent years, the concept of competition has emerged as a new paradigm in economic development. Competition captures the awareness of both the limitations and challenges posed by global competition, at a time when effective government action is constrained by budgetary constraints and the private sector faces significant barriers to competing in domestic and international markets. The Global Competitiveness Report of the World Economic Forum defines competitiveness as "the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country".

The term is also used to refer in a broader sense to the economic competition of countries, regions or cities. Recently, countries are increasingly looking at their competition on global markets. Ireland (1997), Saudi Arabia (2000), Greece (2003), Croatia (2004), Bahrain (2005), the Philippines (2006), Guyana, the Dominican Republic and Spain (2011) are just some examples of countries that have advisory bodies or special government agencies that tackle competition issues. Even regions or cities, such as Dubai or the Basque Country(Spain), are considering the establishment of such a body.

The institutional model applied in the case of National Competitiveness Programs (NCP) varies from country to country, however, there are some common features. The leadership structure of NCPs relies on strong support from the highest level of political authority. High-level support provides credibility with the appropriate actors in the private sector. Usually, the council or governing body will have a designated public sector leader (president, vice-president or minister) and a co-president drawn from the private sector. Notwithstanding the public sector's role in strategy formulation, oversight, and implementation, national competition programs should have strong, dynamic leadership from the private sector at all levels – national, local and firm. From the outset, the program must provide a clear diagnostic of the problems facing the economy and a compelling vision that appeals to a broad set of actors who are willing to seek change and implement an outward-oriented growth strategy. Finally, most programs share a common view on the importance of networks of firms or "clusters" as an organizing principal for collective action. Based on a bottom-up approach, programs that support the association among private business leadership, civil society organizations, public institutions and political leadership can better identify barriers to competition develop joint-decisions on strategic policies and investments; and yield better results in implementation.

National competition is said to be particularly important for small open economies, which rely on trade, and typically foreign direct investment, to provide the scale necessary for productivity increases to drive increases in living standards. The Irish National Competitiveness Council uses a Competitiveness Pyramid structure to simplify the factors that affect national competition. It distinguishes in particular between policy inputs in relation to the business environment, the physical infrastructure and the knowledge infrastructure and the essential conditions of competitiveness that good policy inputs create, including business performance metrics, productivity, labour supply and prices/costs for business.

Competition is important for any economy that must rely on international trade to balance import of energy and raw materials. The European Union (EU) has enshrined industrial research and technological development (R&D) in her Treaty in order to become more competitive. In 2009, €12 billion of the EU budget (totalling €133.8 billion) will go on projects to boost Europe's competition. The way for the EU to face competition is to invest in education, research, innovation and technological infrastructures.

The International Economic Development Council (IEDC) in Washington, D.C. published the "Innovation Agenda: A Policy Statement on American Competitiveness". This paper summarizes the ideas expressed at the 2007 IEDC Federal Forum and provides policy recommendations for both economic developers and federal policy makers that aim to ensure America remains globally competitive in light of current domestic and international challenges.

International comparisons of national competition are conducted by the World Economic Forum, in its Global Competitiveness Report, and the Institute for Management Development, in its World Competitiveness Yearbook.

Scholarly analyses of national competition have largely been qualitatively descriptive. Systematic efforts by academics to define meaningfully and to quantitatively analyze national competitiveness have been made, with the determinants of national competitiveness econometrically modeled.

A US government sponsored program under the Reagan administration called Project Socrates, was initiated to, 1) determine why US competition was declining, 2) create a solution to restore US competition. The Socrates Team headed by Michael Sekora, a physicist, built an all-source intelligence system to research all competition of mankind from the beginning of time. The research resulted in ten findings which served as the framework for the "Socrates Competitive Strategy System". Among the ten finding on competition was that 'the source of all competitive advantage is the ability to access and utilize technology to satisfy one or more customer needs better than competitors, where technology is defined as any use of science to achieve a function".

Role of infrastructure investments

Some development economists believe that a sizable part of Western Europe has now fallen behind the most dynamic amongst Asia's emerging nations, notably because the latter adopted policies more propitious to long-term investments: "Successful countries such as Singapore, Indonesia and South Korea still remember the harsh adjustment mechanisms imposed abruptly upon them by the IMF and World Bank during the 1997–1998 'Asian Crisis' […] What they have achieved in the past 10 years is all the more remarkable: they have quietly abandoned the "Washington consensus" [the dominant Neoclassical perspective] by investing massively in infrastructure projects […] this pragmatic approach proved to be very successful."

The relative advancement of a nation's transportation infrastructure can be measured using indices such as the (Modified) Rail Transportation Infrastructure Index (M-RTI or simply 'RTI') combining cost-efficiency and average speed metrics

Trade competition

While competition is understood at a macro-scale, as a measure of a country's advantage or disadvantage in selling its products in international markets. Trade competition can be defined as the ability of a firm, industry, city, state or country, to export more in value added terms than it imports.

Using a simple concept to measure heights that firms can climb may help improve execution of strategies. International competition can be measured on several criteria but few are as flexible and versatile to be applied across levels as Trade Competitiveness Index (TCI).

Trade Competitiveness Index (TCI)

TCI can be formulated as ratio of forex (FX) balance to total forex as given in equation below. It can be used as a proxy to determine health of foreign trade, The ratio goes from −1 to +1; higher ratio being indicative of higher international trade competitiveness.

In order to identify exceptional firms, trends in TCI can be assessed longitudinally for each company and country. The simple concept of trade competitiveness index (TCI) can be a powerful tool for setting targets, detecting patterns and can also help with diagnosing causes across levels. Used judiciously in conjunction with the volume of exports, TCI can give quick views of trends, benchmarks and potential. Though there is found to be a positive correlation between the profits and forex earnings, we cannot blindly conclude the increase in the profits is due to the increase in the forex earnings. The TCI is an effective criteria, but need to be complemented with other criteria to have better inferences.

Excessive competition

Excessive competition is a competition that supply is excessive to demand chronically, and it harm the producer on the interest. Excessive competition is also caused when supply of goods or services which should be sold immediately is greater than demand. So on labor market, the labor will be left always into the excessive competition.

Criticism

Critiques of perfect competition

Economists do not all agree to the practicability of perfect competition. There is debate surrounding how relevant it is to real world markets and whether it should be a market structure that should be used as a benchmark.

Neoclassical economists believe that perfect competition creates a perfect market structure, with the best possible economic outcomes for both consumers and society. In general, they do not claim that this model is representative of the real world. Neoclassical economists argue that perfect competition can be useful, and most of their analysis stems from its principles.

Economists that are critical of the neoclassical reliance on perfect competition in their economic analysis believe that the assumptions built into the model are so unrealistic that the model cannot produce any meaningful insights. The second line of critic to perfect competition is the argument that it is not even a desirable theoretical outcome. These economists believe that the criteria and outcomes of perfect competition do not achieve an efficient equilibrium in the market and other market structures are better used as a benchmark within the economy.

Critique about national competition

Krugman (1994) points to the ways in which calls for greater national competition frequently mask intellectual confusion arguing that, in the context of countries, productivity is what matters and "the world's leading nations are not, to any important degree, in economic competition with each other." Krugman warns that thinking in terms of competition could lead to wasteful spending, protectionism, trade wars, and bad policy. As Krugman puts it in his crisp, aggressive style "So if you hear someone say something along the lines of 'America needs higher productivity so that it can compete in today's global economy', never mind who he is, or how plausible he sounds. He might as well be wearing a flashing neon sign that reads: 'I don't know what I'm talking about'."

If the concept of national competition has any substantive meaning it must reside in the factors about a nation that facilitates productivity and alongside criticism of nebulous and erroneous conceptions of national competition systematic and rigorous attempts like Thompson's need to be elaborated.