| 1929 Arab riots in Palestine | |

|---|---|

| Part of the intercommunal violence in Mandatory Palestine | |

During the 1929 Palestine riots, Jewish families at Jaffa Gate fleeing from the Old City of Jerusalem | |

| Location | British Mandate of Palestine (Safed, Hebron, Jerusalem, Jaffa) |

| Date | 23–29 August 1929 |

| Deaths | 133 Jews 116 Arabs |

| Injured | 339 Jews 232+ Arabs |

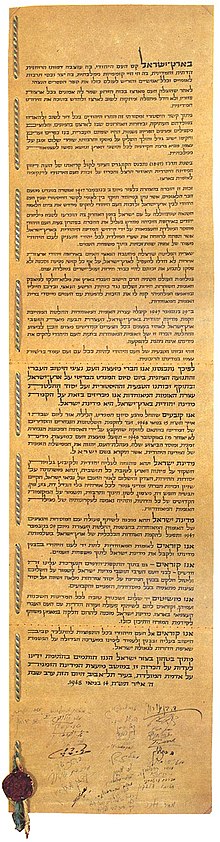

The 1929 Palestine riots, Buraq Uprising (Arabic: ثورة البراق, Thawrat al-Burāq) or the Events of 1929 (Hebrew: מאורעות תרפ"ט, Meora'ot Tarpat, lit. Events of 5689 Anno Mundi), was a series of demonstrations and riots in late August 1929 in which a longstanding dispute between Muslims and Jews over access to the Western Wall in Jerusalem escalated into violence.

The riots took the form, for the most part, of attacks by Arabs on Jews accompanied by destruction of Jewish property. During the week of riots, from 23 to 29 August, 133 Jews were killed by Arabs, and 339 Jews were injured, most of whom were unarmed. There were 116 Arabs killed and at least 232 wounded, mostly by the Mandate police suppressing the riots. Around 20 Arabs were killed by Jewish attackers and indiscriminate British gunfire. After the riots, 174 Arabs and 109 Jews were charged with murder or attempted murder; around 40% of Arabs and 3% of Jews were subsequently convicted. During the riots, 17 Jewish communities were evacuated.

The British-appointed Shaw Commission found that the fundamental cause of the violence, "without which in our opinion disturbances either would not have occurred or would have been little more than a local riot, is the Arab feeling of animosity and hostility towards the Jews consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future", as well as Arab fears of Jewish immigrants "not only as a menace to their livelihood but as a possible overlord of the future". With respect to the triggering of the riots, the Commission found that the incident that "contributed most to the outbreak was the Jewish demonstration at the Wailing Wall on 15 August 1929".

Avraham Sela described the riots as "unprecedented in the history of the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine, in duration, geographical scope and direct damage to life and property".

Background

Religious significance

The Western Wall is one of the holiest of Jewish sites, as it is a remnant of the ancient Second Temple compound destroyed in 70 CE. The Jews, through the practice of centuries, had established a right of access to the Western Wall for the purposes of their devotions. As part of the Temple Mount the Western Wall was under the control of the Muslim religious trust, the Waqf. Muslims consider the wall to be part of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in Islam, and according to Islamic tradition the place where Muhammad tied his steed, Buraq, before his night journey to heaven. There had been a few serious incidents resulting from these differences.

1925 ruling

As a result of an incident that occurred in September 1925, a ruling was made which forbade the Jews to bring seats and benches to the Wall even though these were intended for worshippers who were aged and infirm. The Muslims linked any adaptions to the site with "the Zionist project" and feared that they would be the first step in turning the site into a synagogue and taking it over.

Several months earlier Zionist leader Menachem Ussishkin gave a speech demanding "a Jewish state without compromises and without concessions, from Dan to Be'er Sheva, from the great sea to the desert, including Transjordan." He concluded, "Let us swear that the Jewish people will not rest and will not remain silent until its national home is built on our Mt Moriah," a reference to the Temple Mount.

1928 incident

In September 1928, Jews praying at the Wall on Yom Kippur placed chairs and a mechitza that looked like a simple room divider of cloth covering a few wooden frames to separate the men and women. Jerusalem's British commissioner Edward Keith-Roach, while visiting a Muslim religious court building overlooking the prayer area, mentioned to a constable that he had never seen it at the wall before, although the constable had seen it earlier that day and had not given it any attention. The sheikhs hosting the commissioner immediately protested the screen on the grounds that it violated the Ottoman status quo forbidding Jews from bringing physical structures, even temporary furniture, into the area due to Muslim fears of Zionist expropriation of the site. The sheikhs disclaimed responsibility for what could happen if the screen was not taken down, and Keith-Roach told the Ashkenazic beadle to remove the screen because of the Arabs' demands. The beadle requested that the screen remained standing until the end of the prayer service, to which Keith-Roach agreed. While the commissioner was visiting a synagogue, Attorney General Norman Bentwich had his request to keep the screen until after the fast rejected by the commissioner, who ordered the constable to ensure that it was removed by morning. The constable feared that the screen meant trouble, and had the commissioner's order signed and officially stamped, speaking again with the beadle that evening. When the screen remained in the morning, the constable sent ten armed policemen to remove it. The policemen charged the small group near the screen and were urged by nearby Arab residents to attack the assembled Jews. Jewish worshipers who had gathered began to attack the policemen. The screen was eventually destroyed by the policemen. The constable had infuriated his superiors due to his use of excessive force without good judgement, but the British government later issued a statement defending his actions.

Rabbi Aaron Menachem Mendel Guterman (1860-1934), the third rebbe of the Radzymin Hasidic dynasty, while visiting Jerusalem from Poland, is described as being the person responsible for erecting the canvas screen that became the center of the 1928 incident. Although Guterman used his own funds to erect the screen, the lack of any prior consultation with the British and Arab authorities resulted in their anger over the event.

Although screens had been set up temporarily at the site before, and other prohibitions were ignored or relaxed at times, the violent confrontation over the latest screen would engender further violence. The internal politics of both sides were also willing to adopt extreme positions and make use of religious symbols to stir up popular support.

Subsequent events

Zionist literature published throughout the world used the imagery of a domed structure on the Temple Mount to symbolize their national aspirations. A Zionist flag was depicted atop of a building very reminiscent of the Dome of the Rock in one publication, which was later picked up and redistributed by Arab propagandists.

Haj Amin al Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem distributed leaflets to Arabs in Palestine and throughout the Arab world which claimed that the Jews were planning to take over the al-Aqsa Mosque. The leaflet stated that the Government was "responsible for any consequences of any measures which the Moslems may adopt for the purpose of defending the holy Burak themselves in the event of the failure of the Government...to prevent any such intrusion on the part of the Jews." A memorandum issued by the Moslem Supreme Council stated, "Having realized by bitter experience the unlimited greedy aspirations of the Jews in this respect, Moslems believe that the Jews' aim is to take possession of the Mosque of Al-Aqsa gradually on the pretence that it is the Temple," and it advised the Jews "to stop this hostile propaganda which will naturally engender a parallel action in the whole Moslem world, the responsibility for which will rest with the Jews."

The Shaw Commission stated that some sections of the Arabic Press had reproduced documents concerning the Wailing Wall which "were of a character likely to excite any susceptible readers." In addition, it stated that "there appeared in the Arabic Press a number of articles, which, had they been published in England or in other western countries, would unquestionably have been regarded as provocative." One consequence was that Jewish worshippers frequently were subjected to beatings and stoning.

In October 1928, the Grand Mufti organised new construction next to and above the Wall. Mules were driven through the praying area often dropping excrement, and waste water was thrown on Jews. A muezzin was appointed to perform the Islamic call to prayer directly next to the Wall, creating noise exactly when the Jews were conducting their prayers. The Jews protested at these provocations and tensions increased.

Zionists began making demands for control over the wall; some went as far as to call openly for the rebuilding of the Temple, increasing Muslim fears over Zionist intentions. Ben-Gurion said the wall should be "redeemed," predicting it could be achieved in as little as "another half a year." During the spring of 1929 the Revisionist newspaper edited by right-wing leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky, ran a long campaign claiming Jewish rights over the wall and its pavement, going as far as calling for "insubordination and violence," and pleading that Jews not stop protesting and demonstrating until the Wall is "restored to us."

On 6 August the British police force in Palestine established a police post beside the wall. On 14 August the Haganah and Brit Trumpeldor held a meeting in Tel Aviv attended by 6,000 people objecting to 1928 Commission's conclusion that the Wall was Muslim property.

March to the Western Wall and counter demonstrations, 14–15 August

Joseph Klausner who formed the Pro–Wailing Wall Committee helped organize several demonstrations, beginning on 14 August 1929 when 6,000 youths marched around the wall of the old city of Jerusalem.

On Thursday, 15 August, during the Jewish fast of Tisha B'Av, several hundred members of Klausner's right-wing group – described by Professor Michael J. Cohen as "brawny youths with staves" – marched to the Western Wall shouting "the Wall is ours," raised the Jewish national flag, sang Hatikvah (the Jewish anthem). The group included members of Vladimir Jabotinsky's Revisionist Zionism movement Betar youth organization, under the leadership of Jeremiah Halpern. Rumors circulated among the Arabs that the procession had attacked local residents and cursed the name of Muhammad. The Shaw report later concluded that the crowd was peaceful and allegations that the crowd were armed with iron bars were not correct, but that there may have been threatening cries made by some "undesirable elements" in the Jewish procession. Leaders of the Palestine Zionist Executive were reportedly alarmed by the activities of the Revisionists as well as "embarrassed" and fearful of an "accident" and had notified the authorities of the march in advance, who provided a heavy police escort in a bid to prevent any incidents.

On Friday, 16 August after a sermon, a demonstration organized by the Supreme Muslim Council marched to the Wall. The Acting High Commissioner summoned Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini and informed him that he had never heard of such a demonstration being held at the Wailing Wall, and that it would be a terrible shock to the Jews who regarded the Wall as a place of special sanctity to them. At the Wall, the crowd burnt prayer books, liturgical fixtures and notes of supplication left in the Wall's cracks, and the beadle was injured. The demonstrations spread to the Jewish commercial area of town.

Inflammatory articles calculated to incite disorder started to appear in the Arab media and one flyer, signed by "the Committee of the Holy Warriors in Palestine" stated that the Jews had violated the honor of Islam, and declared: "Hearts are in tumult because of these barbaric deeds, and the people began to break out in shouts of 'war, Jihad ... rebellion.' ... O Arab nation, the eyes of your brothers in Palestine are upon you ... and they awaken your religious feelings and national zealotry to rise up against the enemy who violated the honor of Islam and raped the women and murdered widows and babies."

On the same afternoon, the Jewish newspaper Doar HaYom – of which Jabotinsky was the editor – published an inflammatory leaflet describing the Muslim march, based partially on statements by Wolfgang von Weisl, which "in material particulars was incorrect" according to the Shaw report. On 18 August, Haaretz criticised Doar HaYom in an article entitled "He who Sows the Wind shall Reap the Whirlwind": "The poison of propaganda was dripping from its columns daily until it poisoned the atmosphere and brought about the Thursday demonstration....and this served as a pretext to the wild demonstration of the Arabs."

Escalation, 16–22 August

The next day an incident which "in its origin was of a personal nature" was sparked when a 17-year-old Sephardic Jew named Abraham Mizrachi was fatally stabbed by an Arab at the Maccabi grounds near Mea Shearim and the Bukharim quarter, on the outskirts of the village lands of Lifta, following a quarrel which began when he and his friends tried to retrieve their lost football from an Arab girl after it had rolled into an Arab-owned tomato field. A Jewish crowd attacked and severely wounded the policeman who arrived to arrest the Arab responsible, and then attacked and burned neighbouring Arab tents and shacks erected by Lifta residents and wounded their occupants; the wounded included an Arab youth named 'Ali 'Abdallah Hasan who was chosen at random to be stabbed in retaliation.

Mizrachi died on 20 August and his funeral became the occasion for a serious anti-Arab demonstration. It was suppressed by the same force that had been employed in the initial incident. A late-night meeting initiated the following day by the Jewish leadership, at which acting high commissioner Harry Luke, Jamal al-Husayni, and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi were present, failed to produce a call for an end to the violence.

Over the following four days period, the Jerusalem police reported 12 separate attacks by Jews on Arabs and seven attacks by Arabs on Jews.

On 21 August, the Palestine Zionist Executive telegrammed the Zionist Organization describing the general excitement and the Arab fear of the Jews:

"Population again very excited and false alarms caused local panics in various quarters but no further incidents course of day. Arabs also excited and afraid Jews. Desirable insist with home Government need of serious measures assuring public security. We are issuing appeal to public keep calm, refrain from demonstrations, and observe discipline, but feel embarrassed by militant attitude. Doar Hayom and also part of youth influenced by Revisionist agitation. Can you speak to Revisionist leaders?"

Riots

Jerusalem riots, 23 August

The next Friday, 23 August, thousands of Arab villagers streamed into Jerusalem from the surrounding countryside to pray at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, many armed with sticks and knives. The gathering was prompted by rumors that the Zionists were going to march to the Temple Mount and claim ownership, as they had belligerently marched on the Western Wall demanding Jewish ownership 9 days earlier. Harry Luke requested reinforcements from Amman. Towards 09:30 Jewish storekeepers began closing shop and at 11:00, 20–30 gunshots were heard on the Temple Mount, apparently to work up the crowd. Luke telephoned the Mufti to come and calm a mob that had gathered under his window near the Damascus Gate, but the commissioner's impression was that the religious leader's presence was having the opposite effect. By midday friction had spread to the Jewish neighborhood of Mea She'arim where two or three Arabs were killed. The American consulate documented the event in detail, reported that the killings had taken place between 12:00 and 12:30. The Shaw report described the excited Arab crowds and that it was clear beyond all doubt that at 12:50 large sections of these crowds were bent on mischief if not on murder. At 13:15, the Arabs began a massacre of the Jews.

Reacting to rumors that two Arabs had been murdered by Jews, Arabs started an attack on Jews in Jerusalem's Old City. The violence quickly spread to other parts of Palestine. The British authorities had fewer than a hundred soldiers, six armoured cars, and five or six aircraft in country; Palestine Police had 1,500 men, but the majority were Arab, with a small number of Jews and 175 British officers. While awaiting reinforcements, many untrained administration officials were required to attach themselves to the police, though the Jews among them were sent back to their offices. Several English theology students visiting from the University of Oxford were deputized. While a number of Jews were being killed at the Jaffa Gate, British policemen did not open fire. They reasoned that if they had shot into the Arab crowd, the mob would have turned their anger on the police.

Yemin Moshe was one of the few Jewish neighbourhoods to return fire, but most of Jerusalem's Jews did not defend themselves. At the outbreak of the violence and again in the following days, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi demanded that weapons be handed to the Jews, but was both times refused. By 24 August, 17 Jews were killed in the Jerusalem area. The worst killings occurred in Hebron and Safed while others were killed in Motza, Kfar Uria, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. There were many isolated attacks on Jewish villages, and in six cases, villages were entirely destroyed, accompanied by looting and burning. In Haifa and Jaffa, the situation deteriorated and a police officer succeeded in warding off an attack on the quarter between Jaffa and Tel Aviv by firing on an Arab crowd.

The administrative director of Haddasah hospital in Jerusalem sent a cable to New York describing the casualties and that Arabs were attacking several Jewish hospitals.

According to the Shaw Report, the disturbances were not premeditated and did not occur simultaneously but spread from Jerusalem through a period of days to most outlying centres of population. The Shaw report found that the "outbreak in Jerusalem on 23 August was from the beginning an attack by Arabs on Jews for which no excuse in the form of earlier murders by Jews has been established."

Later on 23 August, the British authorities armed 41 Jewish special constables, 18 Jewish ex-soldiers and a further 60 Jews civilians were issued with staves to assist in the defense of Jewish quarters in Jerusalem. The following day, Arab notables issued a statement that "many rumours and reports of various kinds have spread to the effect that Government had enlisted and armed certain Jews, that they had enrolled Jewish ex-soldiers who had served in the Great War; and the Government forces were firing at Arabs exclusively." The Mufti of Jerusalem stated that there was a large crowd of excited Arabs in the Haram area who were also demanding arms, and that the excited crowd in the Haram area took the view that the retention of Jews as special constables carrying arms was a breach of faith by the Government. The Government initially denied the rumours, but by 27 August they were forced to disband and disarm the special constables.

Motza murders, 24 August

The Jewish village of Motza, west of Jerusalem, had good relationships with the Arab community. The Haganah had offered to provide protection for the Jewish families in the town, but many such as the Makleff family rejected the offer as they did not believe the Arabs would harm them.

In the afternoon of 24 August, Arabs from neighbouring Qalunya entered Motza and invaded the house of the Maklef family. Mr. Makleff was murdered along with his son and two rabbis (including the Gargždai-born Shlomo Zalman Shach who had been invited to the household as guests. Mr. Maklef's wife, Chaya, was tortured by the Arabs who hanged her on a fence. The two daughters of the family were raped and murdered. Several houses including the Maklef's were set on fire.

When the British police and Haganah respondents arrived to the town they brought Chaya to the hospital but she died of her injuries. The survivors were three children who managed to jump out the balcony and hide in the Jewish Broza family's house. In later years one of these children, Mordechai Maklef, would become the Israel Defense Forces' third chief of staff.

Hebron massacre, 24 August

On 20 August, Haganah leaders proposed to provide defence for 600 Jews of the Old Yishuv in Hebron, or to help them evacuate. However, the leaders of the Hebron community declined these offers, insisting that they trusted the A'yan (Arab notables) to protect them.

On 24 August 1929 in Hebron, Arab mobs attacked the Jewish quarter killing and raping men, women and children and looting Jewish property. They killed between 65 and 68 Jews and wounded 58, with some of the victims being tortured, or mutilated. Sir John Chancellor, the British High Commissioner visited Hebron and later wrote to his son, "The horror of it is beyond words. In one house I visited not less than twenty-five Jews men and women were murdered in cold blood." Sir Walter Shaw concluded in The Palestine Disturbances report that "unspeakable atrocities have occurred in Hebron.

The Shaw report described the attack, "Arabs in Hebron made a most ferocious attack on the Jewish ghetto and on isolated Jewish houses lying outside the crowded quarters of the town. More than 60 Jews – including many women and children – were murdered and more than 50 were wounded. This savage attack, of which no condemnation could be too severe, was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. Jewish synagogues were desecrated, a Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked, and only the exceptional personal courage displayed by Mr. Cafferata – the one British Police Officer in the town – prevented the outbreak from developing into a general massacre of the Jews in Hebron."

The lone British policeman in the town, Raymond Cafferata, who, "killed as many of the murderers as he could, taking to his fists even," was overwhelmed, and the reinforcements he called for did not arrive for 5 hours–leading to severe recriminations. Hundreds of Jews were saved by Arab neighbours who offered them sanctuary from the mob by hiding them in their own houses while others survived by taking refuge in the British police station at Beit Romano on the outskirts of the city. When the massacre ended, the surviving Jews were evacuated by the British.

Hebron yeshiva massacre

The Hebron Yeshiva, a branch of the famed Slobodka yeshiva, was also attacked during the riots. On Friday, 23 August, an Arab crowd gathered outside it and threw stones through the windows. Only two people were inside, a student and the sexton. The student was grabbed by the Arab crowd, who stabbed him to death; the sexton survived by hiding in a well. The next day, a crowd armed with staves and axes attacked and killed two Jewish boys, one stoned to death and the other stabbed. More than 70 Jews, including the Yeshiva students, sought refuge in the house of Eliezer Dan Slonim, the son of the Rabbi of Hebron, but were massacred by an Arab mob. Survivors and reporters recounted the carnage that occurred at the Slonim residence. Moses Harbater, an 18-year-old was stabbed and two of his fingers were severed. He described at a later trial of some Arab rioters how a fellow student had been mutilated and killed. Forty-two teachers and students were murdered at the yeshiva.

Hadassah hospital attack

The Hadassah Medical Organization operated an infirmary in Hebron. The Beit Hadassah clinic had three floors with the infirmary, the pharmacy and the synagogue on the top floor. Arab rioters destroyed the pharmacy and torched the synagogue and destroyed the Torah scrolls inside.

Jaffa massacre of ‘Awn family

Cases of Jews attacking Arabs and destroying their property were also noted by the Shaw Commission. On the 25 August, reports stated that a group of Jews accompanied by a Jewish policeman, later asserted to be Simha Hinkis on the government payroll, attacked the home of Sheikh ‘Abd al-Chani ‘Awn (50), the imam of the neighbourhood mosque. On breaking in, according to the Arab account, they disemboweled him and killed six members of his family. His wife, nephew, and 3 year old son were also mutilated by having their heads smashed in. A subsequent investigation stated 5 adults had been killed, but no children died: a five year old child had been shot, and a two-month old baby had been struck on the ear, temple and cheek with a blunt instrument. Both survived. A third child, the Sheikh's 9 year old son, survived untouched beneath his mother's body. The husband of one of the women shot, present at the time, in hiding, later testified in court the killer had been a Jewish policeman, as did the material evidence. Hinkis was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging, a sentence later commuted on appeal, after the prosecutor was reportedly bribed, to 15 years on the grounds prior intent had not be established. Hinkis was released from prison under an amnesty in 1935, and died in 1988.

Desecration of the Nebi Akasha Mosque, 26 August

On 26 August, the Nebi Akasha Mosque in Jerusalem was attacked by a group of Jews. According to the Shaw Report, the mosque was a "sacred shrine of great antiquity held in much veneration by the Moslems." The mosque was badly damaged and the tombs of the prophets which it contained were desecrated.

Attack on Mishmar HaEmek

The kibbutz of Mishmar HaEmek was attacked on 26 August by an Arab mob, which was dispersed by the locals and British police. On the following day the British authorities ordered the kibbutz members to evacuate. On 28 August an Arab mob attacked the empty kibbutz again, burning its barn, uprooting trees and vandalizing its cemetery. The members of the Kibbutz returned on 7 September.

Safed massacre, 29 August

In Safed on 29 August, 18 Jews were killed (some sources say 20) and 80 wounded. The attackers looted and set fire to houses and killed Jewish inhabitants. The main Jewish street was looted and burned.

The members of the Commission of Inquiry visited the town on 1 November 1929. The Shaw report stated:

"At about 5:15 pm, on the 29th of August, Arab mobs attacked the Jewish ghetto in Safed...in the course of which some 45 Jews were killed or wounded, several Jewish houses and shops were set on fire, and there was a repetition of the wanton destruction which had been so prominent a feature of the attack at Hebron."

An eyewitness describing the pogrom that took place in Safed, perpetrated by Arabs from Safed and local villages, armed with weapons and kerosene tins. He observed mutilated and burned bodies of victims and the burnt body of a woman tied to a window. Several people were brutally killed. A schoolteacher, wife, and mother and a lawyer, were cut to pieces with knives and the attackers entered an orphanage and smashed children's heads and cut off their hands. Another victim was stabbed repeatedly and trampled to death.

David Hacohen, a resident of Safed, described the carnage in his diary:

"We set out on Saturday morning. … I could not believe my eyes. … I met some of the town's Jewish elders, who fell on my neck weeping bitterly. We went down alleys and steps to the old town. Inside the houses I saw the mutilated and burned bodies of the victims of the massacre, and the burned body of a woman tied to the grille of a window. Going from house to house, I counted ten bodies that had not yet been collected. I saw the destruction and the signs of fire. Even in my grimmest thoughts I had not imagined that this was how I would find Safed where "calm prevailed."

The local Jews gave me a detailed description of how the tragedy had started. The pogrom began on the afternoon of Thursday, August 29, and was carried out by Arabs from Safed and from the nearby villages, armed with weapons and tins of kerosene. Advancing on the street of the Sefardi Jews from Kfar Meron and Ein Zeitim, they looted and set fire to houses, urging each other on to continue with the killing. They slaughtered the schoolteacher, Aphriat, together with his wife and mother, and cut the lawyer, Toledano, to pieces with their knives. Bursting into the orphanages, they smashed the children's heads and cut off their hands. I myself saw the victims. Yitshak Mammon, a native of Safed who lived with an Arab family, was murdered with indescribable brutality: he was stabbed again and again, until his body became a bloody sieve, and then he was trampled to death. Throughout the whole pogrom the police did not fire a single shot."

A Scottish missionary working in Safed at the time stated:

"On Saturday August 24, there was a demonstration of Moslems along the road past the mission property. They came beating drums and breaking the windows of Jewish houses en route...On the afternoon of Thursday the 29th... one of our church members came running to tell us that 'all the Jews were being killed.' A few minutes later we heard women shrieking their 'jubilant refrain' from the Moslem quarter and saw men running with axes and bludgeons in their hands, urged on by women...we heard rifle and machine gun fire all around us...Wild Arabs had come up from the valley unexpectedly into the Jewish quarter and began at once a systematic slaughter of the Jews. Some escaped with injury only but 22 were killed outright in the town...The inhumanity of the attack was beyond conception. Women were gashed in the chest, babies were cut on the hands and feet, old people were killed and plundered."

The Safed massacre marked the end of the disturbances.

Other areas

The British police had to open fire to prevent attacks in Nablus and Jaffa, and a lone police officer succeeded in warding off an attack on the quarter between Jaffa and Tel Aviv by firing on an Arab crowd.

Casualties

Deaths and injuries

According to the Shaw Report, during the week of riots from 23 to 29 August 116 Arabs and 133 Jews were killed and 232 Arabs and 198 Jews were injured and treated in hospital.

|

|

Deaths | Injuries |

|---|---|---|

| Jews | 133 | 198–241 or 339 |

| Arabs | 116+ (possibly higher) | 232+ (possibly higher) |

The Jewish casualty figures were provided by the Jewish authorities. The Arab casualty figures represented only those actually admitted to hospital and did not include "a considerable number of unrecorded casualties from rifle fire that occurred amongst Arabs."

Many of the 116 reported Arab deaths were as a result of police and military activities, although around 20 of the Arabs killed were not involved in attacks on Jews and were killed as a result of lynchings and revenge attacks by Jews or by indiscriminate gunfire by the British police. Prominent Arab figures in Palestine accused the Palestine police of exclusively firing at Arab rioters and not Jewish ones.

Most Jewish casualties resulted from Arab attacks, although the British authorities noted in the Shaw report that "possibly some of the Jewish casualties were caused by rifle fire by the police or military forces."

Trials and convictions

The riots produced a large number of trials. According to the Attorney-General of Palestine, Norman Bentwich, the following numbers of persons were charged, with the numbers convicted in parentheses.

|

|

Murder | Attempted murder | Looting/arson | Lesser offences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabs | 124 (55) | 50 (17) | 250 (150) | 294 (219) |

| Jews | 70 (2) | 39 (1) | 31 (7) | 21 (9) |

Of those convicted of murder, 26 Arabs and 2 Jews were sentenced to death. The Arabs included 14 convicted for the massacre in Safed and 11 for the massacre in Hebron. The Jewish policeman Hinkis convicted for the murder of five and wounding of two, was sentenced to death but on appeal this was commuted to 15 years imprisonment. Joseph Urphali was convicted by two separate trials, and lost his appeal twice, for the shooting of two Arabs from the roof of his Jaffa house, killing also an Arab who ran to succor the first man he shot.

Some of the Arab convictions were overturned on appeal and all the remaining death sentences were commuted to terms of imprisonment by the High Commissioner except in the case of three Arabs. Atta Ahmed el Zeer, Mohammad Khaleel Jamjoum and Fuad Hassab el Hejazi were hanged on 17 June 1930.

Collective fines were imposed on the Arabs of Hebron, Safed, and some villages. The fine on Hebron was 14,000 pounds. The fines collected, and an additional one hundred thousand pounds, were distributed to the victims, 90 percent of them Jews.

Jewish communities attacked

These Jewish communities were attacked during the riots:

| Name of locality | Date of attack | Date of evacuation | Further details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yesud HaMa'ala | 1 September | 1 September |

|

| Ein Zeitim | 29 August | 29 August | Three residents were killed and the remainder left. |

| Safed | 29 August | 29 August | Massacre of the Jewish population of the city, 18 Jews killed |

| Kfar Hittim | 2 September | N/A | Attack repelled |

| Acre | 29 August | N/A | Attack on Jews in a factory repelled by British police |

| Haifa | 24–26 August | N/A |

|

| Mishmar HaEmek | 26, 28 August | 27 August |

|

| Heftziba | 26 August | N/A | Attack repelled |

| Beit Alfa | 26 August | N/A | Attack repelled |

| Beit She'an | 24 August | 24 August | Jews of the town evacuated, major damage to Jewish property made |

| Jenin | N/A | 29 August | Jews of Jenin evacuated on behalf of the British police |

| Tulkarem | N/A | 29 August | Jews of Tulkarem evacuated on behalf of the British police |

| Nablus | 29 August | 29 August | Jews of Nablus attacked by Arabs and evacuated on behalf of the British police |

| Tel Aviv | 25 August | N/A |

|

| Mazkeret Batya | 27 August | 27 August | Jews of Mazkeret Batya evacuated on behalf of the British police |

| Hulda | 26 August | 27 August |

|

| Kfar Uria | 24 August | 24 August |

|

| Hartuv | 25 August | 25 August | town completely destroyed and abandoned |

| Motza | 24 August | 24 August | Moshav was evacuated after being attacked by residents of Qalunya |

| Ramat Rachel | 23 August | 23 August | Kibbutz destroyed after being attacked by residents of Sur Baher |

| Jerusalem | 23 August | N/A |

|

| Atarot | 26 August | N/A |

|

| Neve Yaakov | 26 August | N/A |

|

| Beer Tuvia | 26 August | 26 August |

|

| Migdal Eder | ? | 24 August | The residents found shelter in Beit Umar but Migdal Eder was completely destroyed, and the residents could not return. |

| Hebron | 24 August | 24 August | Massacre of the Jews of the city, 67 Jews killed. |

| Gaza | N/A | 25 August | Jews of Gaza evacuated by train to Tel Aviv on behalf of the British police |

| Kfar Malal | ? | ? | Several attacks repelled by the residents |

Aftermath

A few dozen Jewish families returned to Hebron in 1931 to reestablish the community, but all but one of them were evacuated from Hebron at the outset of the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine. The last family left in 1947.

The Arabs in the region, led by the Palestine Arab Congress, imposed a boycott on Jewish-owned businesses after the riots.

Historiography

Shaw Commission of Enquiry

A commission of enquiry, led by Sir Walter Shaw, took public evidence for several weeks. The main conclusions of the commission were as follows. [Material not in brackets is verbatim.]

- The fundamental cause, without which in our opinion disturbances either would not occurred or would have been little more than a local riot, is the Arab feeling of animosity and hostility towards the Jews consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future. ... The feeling as it exists today is based on the twofold fear of the Arabs that by Jewish immigration and land purchases they may be deprived of their livelihood and in time pass under the political domination of the Jews.

- In our opinion the immediate causes of the outbreak were:-

- The long series of incidents connected with the Wailing Wall... These must be regarded as a whole, but the incident among them which in our view contributed most to the outbreak was the Jewish demonstration at the Wailing Wall on the 15th of August, 1929. Next in importance we put the activities of the Society for the Protection of the Moslem Holy Places and, in a lesser degree, of the Pro-Wailing Wall Committee.

- Excited and intemperate articles which appeared in some Arabic papers, in one Hebrew daily paper and in a Jewish weekly paper...

- Propaganda among the less-educated Arab people of a character calculated to incite them.

- The enlargement of the Jewish Agency.

- The inadequacy of the military forces and of the reliable police available.

- The belief...that the decisions of the Palestine Government could be influenced by political considerations.

- The outbreak in Jerusalem on the 23rd of August was from the beginning an attack by Arabs on Jews for which no excuse in the form of earlier murders by Jews has been established.

- The outbreak was not premeditated.

- [The disturbances] took the form, in the most part, of a vicious attack by Arabs on Jews accompanied by wanton destruction of Jewish property. A general massacre of the Jewish community at Hebron was narrowly averted. In a few instances, Jews attacked Arabs and destroyed Arab property. These attacks, though inexcusable, were in most cases in retaliation for wrongs already committed by Arabs in the neighbourhood in which the Jewish attacks occurred.

- [In his activities connected to the dispute over the Holy Places] the Mufti was influenced by the twofold desire to confront the Jews and to mobilize Moslem opinion on the issue of the Wailing Wall. He had no intention of utilizing this religious campaign as the means of inciting to disorder.

- ...in the matter of innovations of practice [at the Wailing Wall] little blame can be attached to the Mufti in which some Jewish religious authorities also would not have to share. ...no connection has been established between the Mufti and the work of those who either are known or are thought to have engaged in agitation or incitement. ... After the disturbances had broken out the Mufti co-operated with the Government in their efforts both to restore peace and to prevent the extension of disorder.

- [No blame can be properly attached to the British government for failing to provide armed reinforcements, withholding of fire, and similar charges.]

The Commission recommended the government to reconsider its policies as to Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews, which led directly to the Hope Simpson Royal Commission in 1930.

The Commission member Henry Snell signed the report but added a Note of Reservation. Although he was satisfied that the Mufti was not directly responsible for the violence or had connived at it, he believed the Mufti was aware of the nature of the anti-Zionist campaign and the danger of disturbances. He therefore attributed to the Mufti a greater share of the blame than the official report had. Snell also disagreed with the commission on matters of Jewish immigration and did not support restrictions on Jewish land purchases. Regarding the immediate causes of the outbreak, Snell agreed with the Commission's main findings.