Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included involuntary servitude, penal servitude, and imprisonment with hard labour. The term may refer to several related scenarios: labour as a form of punishment, the prison system used as a means to secure labour, and labour as providing occupation for convicts. These scenarios can be applied to those imprisoned for political, religious, war, or other reasons as well as to criminal convicts.

Large-scale implementations of penal labour include labour camps, prison farms, penal colonies, penal military units, penal transportation, or aboard prison ships.

Punitive versus productive labour

Punitive labour, also known as convict labour, prison labour, or hard labour, is a form of forced labour used in both the past and the present as an additional form of punishment beyond imprisonment alone. Punitive labour encompasses two types: productive labour, such as industrial work; and intrinsically pointless tasks used as primitive occupational therapy, punishment, or physical torment.

Sometimes authorities turn prison labour into an industry, as on a prison farm or in a prison workshop. In such cases, the pursuit of income from their productive labour may even overtake the preoccupation with punishment or reeducation as such of the prisoners, who are then at risk of being exploited as slave-like cheap labour (profit may be minor after expenses, e.g. on security). This is sometimes not the case, and the income goes to defray the costs of the prison.

Victorian inmates commonly worked the treadmill. In some cases, it was productive labour to grind grain (an example of using convict labour to meet costs); in others, it served no purpose. Similar punishments included turning the crank machine or carrying cannonballs. Semi-punitive labour also included oakum-picking: teasing apart old tarry rope to make caulking material for sailing vessels.

British Empire

Imprisonment with hard labour was first introduced into English law with the Criminal Law Act 1776 (16 Geo. 3. c. 43), also known as the "Hulks Act", which authorised prisoners being put to work on improving the navigation of the River Thames in lieu of transportation to the North American colonies, which had become impossible due to the American War of Independence.

The Penal Servitude Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict. c. 99) substituted penal servitude for transportation to a distant British colony, except in cases where a person could be sentenced to transportation for life or for a term not less than fourteen years. Section 2 of the Penal Servitude Act 1857 (20 & 21 Vict. c. 3) abolished the sentence of transportation in all cases and provided that in all cases a person who would otherwise have been liable to transportation would be liable to penal servitude instead. Section 1 of the Penal Servitude Act 1891 makes provision for enactments which authorise a sentence of penal servitude but do not specify a maximum duration. It must now be read subject to section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1948.

Sentences of penal servitude were served in convict prisons and were controlled by the Home Office and the Prison Commissioners. After sentencing, convicts would be classified according to the seriousness of the offence of which they were convicted and their criminal record. First time offenders would be classified in the Star class; persons not suitable for the Star class, but without serious convictions would be classified in the intermediate class. Habitual offenders would be classified in the Recidivist class. Care was taken to ensure that convicts in one class did not mix with convicts in another.

Penal servitude included hard labour as a standard feature. Although it was prescribed for severe crimes (e.g. rape, attempted murder, wounding with intent, by the Offences against the Person Act 1861) it was also widely applied in cases of minor crime, such as petty theft and vagrancy, as well as victimless behaviour deemed harmful to the fabric of society. Notable recipients of hard labour under British law include the prolific writer Oscar Wilde (after his conviction for gross indecency), imprisoned in Reading Gaol.

Labour was sometimes useful. In Inveraray Jail from 1839 prisoners worked up to ten hours a day. Most male prisoners made herring nets or picked oakum (Inveraray was a busy herring port); those with skills were often employed where their skills could be used, such as shoemaking, tailoring or joinery. Female prisoners picked oakum, knitted stockings or sewed.

Forms of labour for punishment included the treadmill, shot drill, and the crank machine.

Treadmills for punishment were used for decades in British prisons beginning in 1818; they often took the form of large paddle wheels some 20 feet in diameter with 24 steps around a six-foot cylinder. Prisoners had to work six or more hours a day, climbing the equivalent of 5,000 to 14,000 vertical feet. While the purpose was mainly punitive, the mills could have been used to grind grain, pump water, or operate a ventilation system.

Shot drill involved stooping without bending the knees, lifting a heavy cannonball slowly to chest height, taking three steps to the right, replacing it on the ground, stepping back three paces, and repeating, moving cannonballs from one pile to another.

The crank machine was a device which turned a crank by hand which in turn forced four large cups or ladles through sand inside a drum, doing nothing useful. Male prisoners had to turn the handle 6,000–14,400 times over the period of six hours a day (1.5–3.6 seconds per turn), as registered on a dial. The warder could make the task harder by tightening an adjusting screw.

The British penal colonies in Australia between 1788 and 1868 provide a major historical example of convict labour, as described above: during that period, Australia received thousands of transported convict labourers, many of whom had received harsh sentences for minor misdemeanours in Britain or Ireland.

As late as 1885, 75% of all prison inmates were involved in some sort of productive endeavour, mostly in private contract and leasing systems. By 1935, the portion of prisoners working had fallen to 44%, and almost 90% of those worked in state-run programmes rather than for private contractors.

England and Wales

Penal servitude was abolished for England and Wales by section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1948. Every enactment conferring power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be construed as conferring power to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of that Act.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 1(2) of that Act.

Northern Ireland

Penal servitude was abolished for Northern Ireland by section 1(1) of the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1953. Every enactment which operated to empower a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case now operates so as to empower that court to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of that Act.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 1(2) of that Act.

Scotland

Penal servitude was abolished in Scotland by section 16(1) of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1949 on 12 June 1950, and imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 16(2) of the act.

Every enactment conferring power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be construed as conferring power to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before 12 June 1950. But this does not empower any court, other than the High Court, to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term exceeding three years.

See section 221 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1975 and section 307(4) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995

China

In pre-Maoist China, a system of labour camps for political prisoners operated by the Kuomintang forces of Chiang Kai-shek existed during the Chinese Civil War from 1938 to 1949. Young activists and students accused of supporting Mao Zedong and his communists were arrested and re-educated in the spirit of anti-communism at the Northwestern Youth Labor Camp.

After the communists took power in 1949 and established the Communist China, laojiao (Re-education through labour) and laogai (Reform through labour) was (and still is in some cases) used as a way to punish political prisoners. They were intended not only for criminals, but also for those deemed to be counter-revolutionary (political and/or religious prisoners). According to an Al Jazeera special report on slavery, China has the largest penal labour system in the world today. Often these prisoners are used to produce products for export to the West. Xinjiang internment camps represent a major source of penal labour in China according to controversial expert, Adrien Zenz. Since 2002, some prisoners have been eligible to receive payment for their labour.

France

Prison inmates can work either for the prison (directly, by performing tasks linked to prison operation, or for the Régie Industrielle des Établissements Pénitentiaires, which produces and sells merchandise) or for a private company, in the framework of a prison/company agreement for leasing inmate labour. Work ceased being compulsory for sentenced inmates in France in 1987. From the French Revolution of 1789, the prison system has been governed by a new penal code. Some prisons became quasi-factories, in the nineteenth century, many discussions focused on the issue of competition between free labour and prison labour. Prison work was temporarily prohibited during the French Revolution of 1848. Prison labour then specialised in the production of goods sold to government departments (and directly to prisons, for example guards' uniforms), or in small low-skilled manual labour (mainly subcontracting to small local industries).

Forced labour was widely used in the African colonies. One of the most emblematic projects, the construction of the Congo-Ocean railway (140 km or 87 miles) cost the lives of 17,000 indigenous workers in 1929. In Cameroon, the 6,000 workers on the Douala-Yaoundé railway line had a mortality rate of 61.7% according to a report by the authorities. Forced labour was officially abolished in the colonies in 1946 under pressure from the Rassemblement démocratique africain and the French Communist Party. In fact, it lasted well into the 1950s.

India

Only convicts sentenced to "rigorous imprisonment" have to undertake work during their prison term. A 2011 Hindustan Times article reported that 99% of convicts that receive such sentences rarely undertake work because most prisons in India do not have sufficient demand for prison labour. In the Indian Penal Code prior to 1949, Many sections prescribed penal servitude for life as a viable punishment. This was removed by Act No. XVII of 1949, Simply known as the Criminal Law (Removal of Racial Discriminations) Act, 1949

Ireland

Penal servitude was abolished in Ireland by section 11(1) of the Criminal Law Act, 1997.

Every enactment conferring a power on a court to pass a sentence of penal servitude in any case must be treated as an enactment empowering that court to pass a sentence of imprisonment for a term not exceeding the maximum term of penal servitude for which a sentence could have been passed in that case immediately before the commencement of the Criminal Law Act 1997.

In the case of any enactment in force on 5 August 1891 (the date on which section 1 of the Penal Servitude Act 1891 came into force) whereby a court had, immediately before the commencement of the Criminal Law Act 1997, power to pass a sentence of penal servitude, the maximum term of imprisonment may not exceed five years or any greater term authorised by the enactment.

Imprisonment with hard labour was abolished by section 11(3) of that Act.

Japan

Most Japanese prisoners are required to engage in prison labour, often in manufacturing parts which are then sold cheaply to private Japanese companies. This practice has raised charges of unfair competition since the prisoners' wages are far below market rate.

During the early Meiji era, in Hokkaido many prisoners were forced to engage in road construction (Shūjin dōro (囚人道路)), mining, and railroad construction, which were severe. It was thought to be a form of unfree labour. It was replaced by indentured servitude (Takobeya-rōdō (タコ部屋労働)).

Netherlands

(Hard) penal labour does not exist in the Netherlands, but a light variant consisting of community service (Dutch: taakstraf) is one of the primary punishments which can be imposed on a convicted offender. The maximum punishment is 240 hours, according to article 22c, part 2 of Wetboek van Strafrecht. The labour must be done in their free time. Reclassering Nederland keeps track of those who were sentenced to community services.

New Zealand

The Criminal Justice Act 1954 abolished the distinction between imprisonment with and without hard labour and replaced 'reformative detention' with 'corrective training', which was later abolished on 30 June 2002.

North Korea

North Korean prison camps can be differentiated into internment camps for political prisoners (Kwan-li-so in Korean) and reeducation camps (Kyo-hwa-so in Korean). According to human rights organisations, the prisoners face forced hard labour in all North Korean prison camps. The conditions are harsh and life-threatening and prisoners are subject to torture and inhumane treatment.

Soviet Union

Another historically significant example of forced labour was that of political prisoners and other persecuted people in labour camps, especially in totalitarian regimes since the 20th century where millions of convicts were exploited and often killed by hard labour and bad living conditions. For much of the history of the Soviet Union and other Communist states, political opponents of these governments were often sentenced to forced labour camps. These forced labour camps are called Gulags, an acronym for the government organization that was in charge of them. The Soviet Gulag camps were a continuation of the punitive labour system of Imperial Russia known as katorga, but on a larger scale. The kulaks were some of the first victims of the Soviet Union's forced labour system. Starting in 1930, nearly two million kulaks were taken to camps in unpopulated regions of the Soviet Union and forced to work in very harsh conditions. Most inmates in the Gulag were ordinary criminals: between 1934 and 1953 there were only two years, 1946 and 1947, when the number of counter-revolutionary prisoners exceeded that of ordinary criminals, partly because the Soviet state had amnestied 1 million ordinary criminals as part of the victory celebrations in 1945. At the height of the purges in the 1930s political prisoners made up 12% of the camp population; at the time of Joseph Stalin's death just over one-quarter. In the 1930s, many ordinary criminals were guilty of crimes that would have been punished with a fine or community service in the 1920s. They were victims of harsher laws from the early 1930s, driven, in part, by the need for more prison camp labour

The Gulags constituted a large portion of the Soviet Union's overall economy. Over half of the tin produced in the Soviet Union was produced by the Gulags. In 1951, the Gulags extracted over four times as much gold as the rest of the economy. Gulag camps also produced all of the diamonds and platinum in the Soviet Union, and forced labourers in the Gulags constituted approximately one fifth of all construction labourers in the Soviet Union.

Between 1930 and 1960, the Soviet regime created many labour camps in Siberia and Central Asia. There were at least 476 separate camp complexes, each one comprising hundreds, even thousands of individual camps. It is estimated that there may have been 5–7 million people in these camps at any one time. In later years the camps also held victims of Joseph Stalin's purges as well as World War II prisoners. It is possible that approximately 10% of prisoners died each year. Out of the 91,000 German soldiers captured after the Battle of Stalingrad, only 6,000 survived the Gulag and returned home. Many of these prisoners, however, had died of illness contracted during the siege of Stalingrad and in the forced march into captivity. More than half of all deaths occurred in 1941–1944, mostly as a result of the deteriorating food and medicine supplies caused by wartime shortages.

Probably the worst of the camp complexes were the three built north of the Arctic Circle at Kolyma, Norilsk and Vorkuta. Prisoners in Soviet labour camps were sometimes worked to death with a mix of extreme production quotas, brutality, hunger and the harsh elements. In all, more than 18 million people passed through the Gulag, with further millions being deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union. The fatality rate was as high as 80% during the first months in many camps. Immediately after the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II, the NKVD massacred about 100,000 prisoners who awaited deportation either to NKVD prisons in Moscow or to the Gulag.

Taiwan

Inmates in Taiwan are required to work during their stay in prison but receive a wage for their labour.

United States

Federal Prison Industries (FPI; doing business as UNICOR since 1977) is a wholly owned United States government corporation created in 1934 that uses penal labour from the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to produce goods and services. FPI is restricted to selling its products and services, which include clothing, furniture, electrical components and vehicle parts, to federal government agencies and has no access to the commercial market. State prison systems also use penal labour and have their own penal labour divisions.

The 13th Amendment of the US Constitution, enacted in 1865, explicitly allows penal labour as it states that "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction". Unconvicted detainees awaiting trial cannot be forced to participate in forced rehabilitative labour programs in prison as it violates the Thirteenth Amendment.

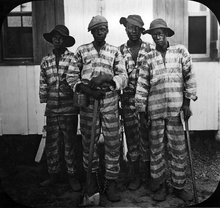

The "convict lease" system became popular throughout the South following the American Civil War and into the 20th century. Since the impoverished state governments could not afford penitentiaries, they leased out prisoners to work at private firms. Reformers abolished convict leasing in the 20th-century Progressive Era. At the same time, labour has been required at many prisons.

In 1934, federal prison officials concerned about growing unrest in prisons lobbied to create a work program. Private companies got involved again in 1979, when Congress passed a law establishing the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program which allows employment opportunities for prisoners in some circumstances.

Penal labour is sometimes used as a punishment in the US military.

Over the years, the courts have held that inmates may be required to work and are not protected by the constitutional prohibition against involuntary servitude. Correctional standards promulgated by the American Correctional Association provide that sentenced inmates, who are generally housed in maximum, medium, or minimum security prisons, be required to work and be paid for that work. Some states require, as with Arizona, all able-bodied inmates to work.

From 2010 to 2015 and again in 2016 and 2018, some prisoners in the US refused to work, protesting for better pay, better conditions and for the end of forced labour. Strike leaders have been punished with indefinite solitary confinement. Forced prison labour occurs in both public and private prisons. The prison labour industry makes over $1 billion per year selling products that inmates make, while inmates are paid very little or nothing in return. In California, 2,500 incarcerated workers fight wildfires for $1 an hour through the CDCR's Conservation Camp Program, saving the state as much as $100 million a year.

The prison strikes of 2018, sponsored by Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, are considered the largest in the country's history. In particular, inmates objected to being excluded from the 13th Amendment which forces them to work for pennies a day, a condition they assert is tantamount to "modern-day slavery".

Prison industries today are often operating at a loss. Some reformers want to remove legal restrictions and change federal employment laws so that workers could be hired on a negotiated laissez-faire basis to work for wages set by the market and the voluntary choices of prisoners to work and employers to pay wages.

Non-punitive prison labour

In a number of penal systems, inmates have the possibility of getting jobs. This may serve several purposes. One goal is to give an inmate a meaningful way to occupy their prison time and a possibility of earning some money. It may also play an important role in resocialisation as inmates may acquire skills that would help them to find a job after release. It may also have an important penological function: reducing the monotony of prison life for the inmate, keeping inmates busy on productive activities, rather than, for example, potentially violent or antisocial activities, and helping to increase inmate fitness, and thus decrease health problems, rather than letting inmates succumb to a sedentary lifestyle.

The classic occupation in 20th-century British prisons was sewing mailbags. This has diversified into areas such as engineering, furniture making, desktop publishing, repairing wheelchairs and producing traffic signs, but such opportunities are not widely available, and many prisoners who work perform routine prison maintenance tasks (such as in the prison kitchen) or obsolete unskilled assembly work (such as in the prison laundry) that is argued to be no preparation for work after release. Classic 20th-century American prisoner work involved making license plates; the task is still being performed by inmates in certain areas.

Many businesses, large and small, already make use of prison workshops to produce high quality goods and services and do so profitably. They are not only investing in prisons but in the future of their companies and the country as a whole. I urge others to follow their lead and seize the opportunity that working prisons offer.

—David Cameron, UK Prime Minister

A significant amount of controversy has arisen with regard to the use of prison labour if the prison in question is privatised. Many of these privatised prisons exist in the Southern United States, where roughly 7% of the prison population are within privately owned institutions. Goods produced through this penal labour are regulated through the Ashurst-Sumners Act which criminalises the interstate transport of such goods.

The advent of automated production in the 20th and 21st century has reduced the availability of unskilled physical work for inmates.

ONE3ONE Solutions, formerly the Prison Industries Unit in Britain, has proposed the development of in-house prison call centers.