An electoral system or voting system is a set of rules that determine how elections and referendums are conducted and how their results are determined. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, non-profit organisations and informal organisations. These rules govern all aspects of the voting process: when elections occur, who is allowed to vote, who can stand as a candidate, how ballots are marked and cast, how the ballots are counted, how votes translate into the election outcome, limits on campaign spending, and other factors that can affect the result. Political electoral systems are defined by constitutions and electoral laws, are typically conducted by election commissions, and can use multiple types of elections for different offices.

Some electoral systems elect a single winner to a unique position, such as prime minister, president or governor, while others elect multiple winners, such as members of parliament or boards of directors. When electing a legislature, areas may be divided into constituencies with one or more representatives or the electorate may elect representatives as a single unit. Voters may vote directly for an individual candidate or for a list of candidates put forward by a political party or alliance. There are many variations in electoral systems, the most common being Party-list proportional representation, first-past-the-post voting, plurality block voting, the two-round (runoff) system and ranked voting (STV or Instant-runoff voting). Mixed systems and some other electoral systems attempt to combine the benefits of non-proportional and proportional systems.

The study of formally defined electoral methods is called social choice theory or voting theory, and this study can take place within the field of political science, economics, or mathematics, and specifically within the subfields of game theory and mechanism design. Impossibility proofs such as Arrow's impossibility theorem demonstrate that when voters have three or more alternatives, no preferential voting system can guarantee the race between two candidates remains unaffected when an irrelevant candidate participates or drops out of the election.

Types of electoral systems

Plurality systems

Plurality voting is a system in which the candidate(s) with the highest number of votes wins, with no requirement to get a majority of votes. In cases where there is a single position to be filled, it is known as first-past-the-post; this is the second most common electoral system for national legislatures, with 58 countries using it for this purpose, the vast majority of which are current or former British or American colonies or territories. It is also the second most common system used for presidential elections, being used in 19 countries.

In cases where there are multiple positions to be filled, most commonly in cases of multi-member constituencies, there are several types of plurality electoral systems. Under block voting (also known as multiple non-transferable vote or plurality-at-large), voters have as many votes as there are seats and can vote for any candidate, regardless of party, a system used in eight countries. In limited voting voters are given fewer votes than there are seats to be filled. Gibraltar is the only territory where this system is in use). Under single non-transferable vote (SNTV) voters can vote for only one candidate, with the candidates receiving the most votes declared the winners; this system is used in Kuwait, the Pitcairn Islands and Vanuatu. In party block voting, voters can only vote for the list of candidates of a single party, with the party receiving the most votes winning all seats. This is used in five countries as part of mixed systems.

The Borda Count is a ranked voting system intended to elect broadly acceptable options or candidates, rather than those preferred by a majority. Under the Borda Count, lower rakings are given lower weighting. This system is used to elect the ethnic minority representatives seats in the Slovenian parliament. The Dowdall system, a multi-member constituency variation on the Borda count, is used in Nauru for parliamentary elections and sees voters rank the candidates. First preference votes are counted as whole numbers; the second preference votes divided by two, third preferences by three; this continues to the lowest possible ranking. The totals for each candidate determines the winners.

Majority systems

Majority voting is a system in which candidates must receive a majority of votes to be elected, either in a runoff election or final round of voting (although in some cases only a plurality is required in the last round of voting if no candidate can achieve a majority). There are two main forms of majoritarian systems, one conducted in a single round of voting using ranked voting and the other using multiple elections, to successively narrow the field of candidates. Both are primarily used for single-member constituencies.

Majoritarian voting can be achieved in a single election using instant-runoff voting (IRV), whereby voters rank candidates in order of preference; this system is used for parliamentary elections in Australia and Papua New Guinea. If no candidate receives a majority of the vote in the first round, the second preferences of the lowest-ranked candidate are then added to the totals. This is repeated until a candidate achieves over 50% of the number of valid votes. If not all voters use all their preference votes, then the count may continue until two candidates remain, at which point the winner is the one with the most votes. A modified form of IRV is the contingent vote where voters do not rank all candidates, but have a limited number of preference votes. If no candidate has a majority in the first round, all candidates are excluded except the top two, with the highest remaining preference votes from the votes for the excluded candidates then added to the totals to determine the winner. This system is used in Sri Lankan presidential elections, with voters allowed to give three preferences.

The other main form of majoritarian system is the two-round system, which is the most common system used for presidential elections around the world, being used in 88 countries. It is also used in 20 countries for electing the legislature. If no candidate achieves a majority of votes in the first round of voting, a second round is held to determine the winner. In most cases the second round is limited to the top two candidates from the first round, although in some elections more than two candidates may choose to contest the second round; in these cases the second round is decided by plurality voting. Some countries use a modified form of the two-round system, such as Ecuador where a candidate in the presidential election is declared the winner if they receive 40% of the vote and are 10% ahead of their nearest rival, or Argentina (45% plus 10% ahead), where the system is known as ballotage.

An exhaustive ballot is not limited to two rounds, but sees the last-placed candidate eliminated in each round of voting. Due to the potentially large number of rounds, this system is not used in any major popular elections, but is used to elect the Speakers of parliament in several countries and members of the Swiss Federal Council. In some formats there may be multiple rounds held without any candidates being eliminated until a candidate achieves a majority, a system used in the United States Electoral College.

Proportional systems

Proportional representation is the most widely used electoral system for national legislatures, with the parliaments of over eighty countries elected by various forms of the system.

Party-list proportional representation is the single most common electoral system and is used by 80 countries, and involves voters voting for a list of candidates proposed by a party. In closed list systems voters do not have any influence over the candidates put forward by the party, but in open list systems voters are able to both vote for the party list and influence the order in which candidates will be assigned seats. In some countries, notably Israel and the Netherlands, elections are carried out using 'pure' proportional representation, with the votes tallied on a national level before assigning seats to parties. However, in most cases several multi-member constituencies are used rather than a single nationwide constituency, giving an element of geographical representation; but this can result in the distribution of seats not reflecting the national vote totals. As a result, some countries have leveling seats to award to parties whose seat totals are lower than their proportion of the national vote.

In addition to the electoral threshold (the minimum percentage of the vote that a party must obtain to win seats), there are several different ways to allocate seats in proportional systems. There are two main types of systems: highest average and largest remainder. Highest average systems involve dividing the votes received by each party by a series of divisors, producing figures that determine seat allocation; for example the D'Hondt method (of which there are variants including Hagenbach-Bischoff) and the Webster/Sainte-Laguë method. Under largest remainder systems, parties' vote shares are divided by the quota (obtained by dividing the total number of votes by the number of seats available). This usually leaves some seats unallocated, which are awarded to parties based on the largest fractions of seats that they have remaining. Examples of largest remainder systems include the Hare quota, Droop quota, the Imperiali quota and the Hagenbach-Bischoff quota.

Single transferable vote (STV) is another form of proportional representation; in STV, voters rank candidates in a multi-member constituency rather than voting for a party list; it is used in Malta and the Republic of Ireland. To be elected, candidates must pass a quota (the Droop quota being the most common). Candidates that pass the quota are elected. If necessary to fill seats, votes are reallocated from the least successful candidates, as well as surplus votes from successful candidates, until all seats are filled by candidates who have passed the quota or until there are only as many remaining candidates as the number of remaining seats.

Mixed systems

Non-compensatory

Compensatory

In several countries, mixed systems are used to elect the legislature. These include parallel voting (also known as mixed-member majoritarian) and mixed-member proportional representation.

In non-compensatory, parallel voting systems, which are used in 20 countries, members of a legislature are elected by two different methods; part of the membership is elected by a plurality or majority vote in single-member constituencies and the other part by proportional representation. The results of the constituency vote have no effect on the outcome of the proportional vote.

In compensatory mixed-member systems the results of the proportional vote are adjusted to balance the seats won in the constituency vote. The mixed-member proportional systems, in use in eight countries, provide enough compensatory seats to ensure that parties have a number of seats approximately proportional to their vote share.

Other systems may be insufficiently compensatory, and this may result in overhang seats, where parties win more seats in the constituency system than they would be entitled to based on their vote share. Variations of this include the Additional Member System, and Alternative Vote Plus, in which voters cast votes for both single-member constituencies and multi-member constituencies; the allocation of seats in the multi-member constituencies is adjusted to achieve an overall seat allocation proportional to parties' vote share by taking into account the number of seats won by parties in the single-member constituencies.

Mixed single vote systems are also compensatory, however they usually use a vote transfer mechanism unlike the seat linkage (top-up) method of MMP and may or may not be able to achieve proportional representation. An unusual form of mixed-member compensatory representation using negative vote transfer, Scorporo, was used in Italy from 1993 until 2006.

Some electoral systems feature a majority bonus system to either ensure one party or coalition gains a majority in the legislature, or to give the party receiving the most votes a clear advantage in terms of the number of seats. San Marino has a modified two-round system, which sees a second round of voting featuring the top two parties or coalitions if there is no majority in the first round. The winner of the second round is guaranteed 35 seats in the 60-seat Grand and General Council. In Greece the party receiving the most votes was given an additional 50 seats, a system which was abolished following the 2019 elections.

In Uruguay, the President and members of the General Assembly are elected by on a single ballot, known as the double simultaneous vote. Voters cast a single vote, voting for the presidential, Senatorial and Chamber of Deputies candidates of that party. This system was also previously used in Bolivia and the Dominican Republic.

Primary elections

Primary elections are a feature of some electoral systems, either as a formal part of the electoral system or informally by choice of individual political parties as a method of selecting candidates, as is the case in Italy. Primary elections limit the risk of vote splitting by ensuring a single party candidate. In Argentina they are a formal part of the electoral system and take place two months before the main elections; any party receiving less than 1.5% of the vote is not permitted to contest the main elections. In the United States, there are both partisan and non-partisan primary elections.

Indirect elections

Some elections feature an indirect electoral system, whereby there is either no popular vote, or the popular vote is only one stage of the election; in these systems the final vote is usually taken by an electoral college. In several countries, such as Mauritius or Trinidad and Tobago, the post of President is elected by the legislature. In others like India, the vote is taken by an electoral college consisting of the national legislature and state legislatures. In the United States, the president is indirectly elected using a two-stage process; a popular vote in each state elects members to the electoral college that in turn elects the President. This can result in a situation where a candidate who receives the most votes nationwide does not win the electoral college vote, as most recently happened in 2000 and 2016.

Systems used outside politics

In addition to the various electoral systems in use in the political sphere, there are numerous others, some of which are proposals and some of which have been adopted for usage in business (such as electing corporate board members) or for organisations but not for public elections.

Ranked systems include Bucklin voting, the various Condorcet methods (Copeland's, Dodgson's, Kemeny-Young, Maximal lotteries, Minimax, Nanson's, Ranked pairs, Schulze), the Coombs' method and positional voting. There are also several variants of single transferable vote, including CPO-STV, Schulze STV and the Wright system. Dual-member proportional representation is a proposed system with two candidates elected in each constituency, one with the most votes and one to ensure proportionality of the combined results. Biproportional apportionment is a system whereby the total number of votes is used to calculate the number of seats each party is due, followed by a calculation of the constituencies in which the seats should be awarded in order to achieve the total due to them.

Cardinal electoral systems allow voters to evaluate candidates independently. The complexity ranges from approval voting where voters simply state whether they approve of a candidate or not to range voting, where a candidate is scored from a set range of numbers. Other cardinal systems include proportional approval voting, sequential proportional approval voting, satisfaction approval voting, highest median rules (including the majority judgment), and the D21 – Janeček method where voters can cast positive and negative votes.

Historically, weighted voting systems were used in some countries. These allocated a greater weight to the votes of some voters than others, either indirectly by allocating more seats to certain groups (such as the Prussian three-class franchise), or by weighting the results of the vote. The latter system was used in colonial Rhodesia for the 1962 and 1965 elections. The elections featured two voter rolls (the 'A' roll being largely European and the 'B' roll largely African); the seats of the House Assembly were divided into 50 constituency seats and 15 district seats. Although all voters could vote for both types of seats, 'A' roll votes were given greater weight for the constituency seats and 'B' roll votes greater weight for the district seats. Weighted systems are still used in corporate elections, with votes weighted to reflect stock ownership.

Rules and regulations

In addition to the specific method of electing candidates, electoral systems are also characterised by their wider rules and regulations, which are usually set out in a country's constitution or electoral law. Participatory rules determine candidate nomination and voter registration, in addition to the location of polling places and the availability of online voting, postal voting, and absentee voting. Other regulations include the selection of voting devices such as paper ballots, machine voting or open ballot systems, and consequently the type of vote counting systems, verification and auditing used.

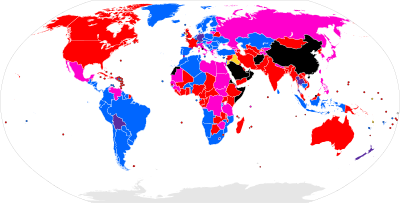

Compulsory voting, not enforced.

Compulsory voting, enforced (only men).

Compulsory voting, not enforced (only men).

Historical: the country had compulsory voting in the past.

Electoral rules place limits on suffrage and candidacy. Most countries's electorates are characterised by universal suffrage, but there are differences on the age at which people are allowed to vote, with the youngest being 16 and the oldest 21. People may be disenfranchised for a range of reasons, such as being a serving prisoner, being declared bankrupt, having committed certain crimes or being a serving member of the armed forces. Similar limits are placed on candidacy (also known as passive suffrage), and in many cases the age limit for candidates is higher than the voting age. A total of 21 countries have compulsory voting, although in some there is an upper age limit on enforcement of the law. Many countries also have the none of the above option on their ballot papers.

In systems that use constituencies, apportionment or districting defines the area covered by each constituency. Where constituency boundaries are drawn has a strong influence on the likely outcome of elections in the constituency due to the geographic distribution of voters. Political parties may seek to gain an advantage during redistricting by ensuring their voter base has a majority in as many constituencies as possible, a process known as gerrymandering. Historically rotten and pocket boroughs, constituencies with unusually small populations, were used by wealthy families to gain parliamentary representation.

Some countries have minimum turnout requirements for elections to be valid. In Serbia this rule caused multiple re-runs of presidential elections, with the 1997 election re-run once and the 2002 elections re-run three times due insufficient turnout in the first, second and third attempts to run the election. The turnout requirement was scrapped prior to the fourth vote in 2004. Similar problems in Belarus led to the 1995 parliamentary elections going to a fourth round of voting before enough parliamentarians were elected to make a quorum.

Reserved seats are used in many countries to ensure representation for ethnic minorities, women, young people or the disabled. These seats are separate from general seats, and may be elected separately (such as in Morocco where a separate ballot is used to elect the 60 seats reserved for women and 30 seats reserved for young people in the House of Representatives), or be allocated to parties based on the results of the election; in Jordan the reserved seats for women are given to the female candidates who failed to win constituency seats but with the highest number of votes, whilst in Kenya the Senate seats reserved for women, young people and the disabled are allocated to parties based on how many seats they won in the general vote. Some countries achieve minority representation by other means, including requirements for a certain proportion of candidates to be women, or by exempting minority parties from the electoral threshold, as is done in Poland, Romania and Serbia.

History

Pre-democratic

In ancient Greece and Italy, the institution of suffrage already existed in a rudimentary form at the outset of the historical period. In the early monarchies it was customary for the king to invite pronouncements of his people on matters in which it was prudent to secure its assent beforehand. In these assemblies the people recorded their opinion by clamouring (a method which survived in Sparta as late as the 4th century BCE), or by the clashing of spears on shields.

Early democracy

Voting has been used as a feature of democracy since the 6th century BCE, when democracy was introduced by the Athenian democracy. However, in Athenian democracy, voting was seen as the least democratic among methods used for selecting public officials, and was little used, because elections were believed to inherently favor the wealthy and well-known over average citizens. Viewed as more democratic were assemblies open to all citizens, and selection by lot, as well as rotation of office.

Generally, the taking of votes was effected in the form of a poll. The practice of the Athenians, which is shown by inscriptions to have been widely followed in the other states of Greece, was to hold a show of hands, except on questions affecting the status of individuals: these latter, which included all lawsuits and proposals of ostracism, in which voters chose the citizen they most wanted to exile for ten years, were determined by secret ballot (one of the earliest recorded elections in Athens was a plurality vote that it was undesirable to win, namely an ostracism vote). At Rome the method which prevailed up to the 2nd century BCE was that of division (discessio). But the system became subject to intimidation and corruption. Hence a series of laws enacted between 139 and 107 BCE prescribed the use of the ballot (tabella), a slip of wood coated with wax, for all business done in the assemblies of the people. For the purpose of carrying resolutions a simple majority of votes was deemed sufficient. As a general rule equal value was made to attach to each vote; but in the popular assemblies at Rome a system of voting by groups was in force until the middle of the 3rd century BCE by which the richer classes secured a decisive preponderance.

Most elections in the early history of democracy were held using plurality voting or some variant, but as an exception, the state of Venice in the 13th century adopted approval voting to elect their Great Council.

The Venetians' method for electing the Doge was a particularly convoluted process, consisting of five rounds of drawing lots (sortition) and five rounds of approval voting. By drawing lots, a body of 30 electors was chosen, which was further reduced to nine electors by drawing lots again. An electoral college of nine members elected 40 people by approval voting; those 40 were reduced to form a second electoral college of 12 members by drawing lots again. The second electoral college elected 25 people by approval voting, which were reduced to form a third electoral college of nine members by drawing lots. The third electoral college elected 45 people, which were reduced to form a fourth electoral college of 11 by drawing lots. They in turn elected a final electoral body of 41 members, who ultimately elected the Doge. Despite its complexity, the method had certain desirable properties such as being hard to game and ensuring that the winner reflected the opinions of both majority and minority factions. This process, with slight modifications, was central to the politics of the Republic of Venice throughout its remarkable lifespan of over 500 years, from 1268 to 1797.

Development of new systems

Jean-Charles de Borda proposed the Borda count in 1770 as a method for electing members to the French Academy of Sciences. His method was opposed by the Marquis de Condorcet, who proposed instead the method of pairwise comparison that he had devised. Implementations of this method are known as Condorcet methods. He also wrote about the Condorcet paradox, which he called the intransitivity of majority preferences. However, recent research has shown that the philosopher Ramon Llull devised both the Borda count and a pairwise method that satisfied the Condorcet criterion in the 13th century. The manuscripts in which he described these methods had been lost to history until they were rediscovered in 2001.

Later in the 18th century, apportionment methods came to prominence due to the United States Constitution, which mandated that seats in the United States House of Representatives had to be allocated among the states proportionally to their population, but did not specify how to do so. A variety of methods were proposed by statesmen such as Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Daniel Webster. Some of the apportionment methods devised in the United States were in a sense rediscovered in Europe in the 19th century, as seat allocation methods for the newly proposed method of party-list proportional representation. The result is that many apportionment methods have two names; Jefferson's method is equivalent to the D'Hondt method, as is Webster's method to the Sainte-Laguë method, while Hamilton's method is identical to the Hare largest remainder method.

The single transferable vote (STV) method was devised by Carl Andræ in Denmark in 1855 and in the United Kingdom by Thomas Hare in 1857. STV elections were first held in Denmark in 1856, and in Tasmania in 1896 after its use was promoted by Andrew Inglis Clark. Party-list proportional representation began to be used to elect European legislatures in the early 20th century, with Belgium the first to implement it for its 1900 general elections. Since then, proportional and semi-proportional methods have come to be used in almost all democratic countries, with most exceptions being former British and French colonies.

Single-winner revival

Perhaps influenced by the rapid development of multiple-winner electoral systems, theorists began to publish new findings about single-winner methods in the late 19th century. This began around 1870, when William Robert Ware proposed applying STV to single-winner elections, yielding instant-runoff voting (IRV). Soon, mathematicians began to revisit Condorcet's ideas and invent new methods for Condorcet completion; Edward J. Nanson combined the newly described instant runoff voting with the Borda count to yield a new Condorcet method called Nanson's method. Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, proposed the straightforward Condorcet method known as Dodgson's method. He also proposed a proportional representation system based on multi-member districts, quotas as minimum requirements to take seats, and votes transferable by candidates through proxy voting.

Ranked voting electoral systems eventually gathered enough support to be adopted for use in government elections. In Australia, IRV was first adopted in 1893 and STV in 1896 (Tasmania). IRV continues to be used along with STV today.

In the United States in the early-20th-century progressive era, some municipalities began to use ranked voting and Bucklin voting, although Bucklin is no longer used in any government elections, and has even been declared unconstitutional in Minnesota. Since the turn away from Bucklin, STV was adopted by more than 20 cities in the U.S. and many cities elsewhere, and by Ireland and Malta for their national elections.

Recent developments

The use of game theory to analyze electoral systems led to discoveries about the effects of certain methods. Earlier developments such as Arrow's impossibility theorem had already shown the issues with Ranked voting systems. Research led Steven Brams and Peter Fishburn to formally define and promote the use of approval voting in 1977. Political scientists of the 20th century published many studies on the effects that the electoral systems have on voters' choices and political parties, and on political stability. A few scholars also studied which effects caused a nation to switch to a particular electoral system.

The study of electoral systems influenced a new push for electoral reform beginning around the 1990s, when proposals were made to replace plurality voting in governmental elections with other methods. New Zealand adopted mixed-member proportional representation for the 1996 general elections, having been approved in a 1993 referendum. After plurality voting was a key factor in the contested results of the 2000 presidential elections in the United States, various municipalities in the United States began to adopt instant-runoff voting, although some of them subsequently returned to their prior method. However, attempts at introducing more proportional systems were not always successful; in Canada there were two referendums in British Columbia in 2005 and 2009 on adopting an STV method, both of which failed. In the United Kingdom, a 2011 referendum on adopting IRV saw the proposal rejected.

In other countries there were calls for the restoration of plurality or majoritarian systems or their establishment where they have never been used; a referendum was held in Ecuador in 1994 on the adoption the two round system, but the idea was rejected. In Romania a proposal to switch to a two-round system for parliamentary elections failed only because voter turnout in the referendum was too low. Attempts to reintroduce single-member constituencies in Poland (2015) and two-round system in Bulgaria (2016) via referendums both also failed due to low turnout.

Comparison of electoral systems

Electoral systems can be compared by different means. Attitudes towards systems are highly influenced by the systems' impact on groups that one supports or opposes, which can make the objective comparison of voting systems difficult. There are several ways to address this problem:

One approach is to define criteria mathematically, such that any electoral system either passes or fails. This gives perfectly objective results, but their practical relevance is still arguable.

Another approach is to define ideal criteria that no electoral system passes perfectly, and then see how often or how close to passing various methods are over a large sample of simulated elections. This gives results which are practically relevant, but the method of generating the sample of simulated elections can still be arguably biased.

A final approach is to consider practical criteria, and then assign a neutral body to evaluate each method according to these criteria or evaluate the performance of countries with these electoral systems. The practical criteria include political fragmentation, voter turnout, wasted votes, complexity of vote counting, and barriers to entry for new political movements. The quality of electoral systems can be measured on outcomes, such as voter turnout, and reduced political apathy. This approach can look at aspects of electoral systems, which the other two approaches miss, but both the definitions of these criteria and the evaluations of the methods are still inevitably subjective.

Arrow's theorem and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem prove that no single-winner system using ranked voting can meet all such criteria simultaneously, while Gibbard's theorem proves the same for all single-winner deterministic voting methods. Instead of debating the importance of different criteria, another method is to simulate many elections with different electoral systems, and estimate the typical overall happiness of the population with the results, their vulnerability to strategic voting, their likelihood of electing the candidate closest to the average voter, etc.

According to a 2006 survey of electoral system experts, their preferred electoral systems were in order of preference:

- Mixed member proportional

- Single transferable vote

- Open list proportional

- Alternative vote

- Closed list proportional

- Single member plurality

- Runoffs

- Mixed member majoritarian

- Single non-transferable vote