A self-replicating machine is a type of autonomous robot that is capable of reproducing itself autonomously using raw materials found in the environment, thus exhibiting self-replication in a way analogous to that found in nature. The concept of self-replicating machines has been advanced and examined by Homer Jacobson, Edward F. Moore, Freeman Dyson, John von Neumann, Konrad Zuse and in more recent times by K. Eric Drexler in his book on nanotechnology, Engines of Creation (coining the term clanking replicator for such machines) and by Robert Freitas and Ralph Merkle in their review Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines which provided the first comprehensive analysis of the entire replicator design space. The future development of such technology is an integral part of several plans involving the mining of moons and asteroid belts for ore and other materials, the creation of lunar factories, and even the construction of solar power satellites in space. The von Neumann probe is one theoretical example of such a machine. Von Neumann also worked on what he called the universal constructor, a self-replicating machine that would be able to evolve and which he formalized in a cellular automata environment. Notably, Von Neumann's Self-Reproducing Automata scheme posited that open-ended evolution requires inherited information to be copied and passed to offspring separately from the self-replicating machine, an insight that preceded the discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule by Watson and Crick and how it is separately translated and replicated in the cell.

A self-replicating machine is an artificial self-replicating system that relies on conventional large-scale technology and automation. The concept, first proposed by Von Neumann no later than the 1940s, has attracted a range of different approaches involving various types of technology. Certain idiosyncratic terms are occasionally found in the literature. For example, the term clanking replicator was once used by Drexler to distinguish macroscale replicating systems from the microscopic nanorobots or "assemblers" that nanotechnology may make possible, but the term is informal and is rarely used by others in popular or technical discussions. Replicators have also been called "von Neumann machines" after John von Neumann, who first rigorously studied the idea. However, the term "von Neumann machine" is less specific and also refers to a completely unrelated computer architecture that von Neumann proposed and so its use is discouraged where accuracy is important. Von Neumann used the term universal constructor to describe such self-replicating machines.

Historians of machine tools, even before the numerical control era, sometimes figuratively said that machine tools were a unique class of machines because they have the ability to "reproduce themselves" by copying all of their parts. Implicit in these discussions is that a human would direct the cutting processes (later planning and programming the machines), and would then assemble the parts. The same is true for RepRaps, which are another class of machines sometimes mentioned in reference to such non-autonomous "self-replication". In contrast, machines that are truly autonomously self-replicating (like biological machines) are the main subject discussed here.

History

The general concept of artificial machines capable of producing copies of themselves dates back at least several hundred years. An early reference is an anecdote regarding the philosopher René Descartes, who suggested to Queen Christina of Sweden that the human body could be regarded as a machine; she responded by pointing to a clock and ordering "see to it that it reproduces offspring." Several other variations on this anecdotal response also exist. Samuel Butler proposed in his 1872 novel Erewhon that machines were already capable of reproducing themselves but it was man who made them do so, and added that "machines which reproduce machinery do not reproduce machines after their own kind". In George Eliot's 1879 book Impressions of Theophrastus Such, a series of essays that she wrote in the character of a fictional scholar named Theophrastus, the essay "Shadows of the Coming Race" speculated about self-replicating machines, with Theophrastus asking "how do I know that they may not be ultimately made to carry, or may not in themselves evolve, conditions of self-supply, self-repair, and reproduction".

In 1802 William Paley formulated the first known teleological argument depicting machines producing other machines, suggesting that the question of who originally made a watch was rendered moot if it were demonstrated that the watch was able to manufacture a copy of itself. Scientific study of self-reproducing machines was anticipated by John Bernal as early as 1929 and by mathematicians such as Stephen Kleene who began developing recursion theory in the 1930s. Much of this latter work was motivated by interest in information processing and algorithms rather than physical implementation of such a system, however. In the course of the 1950s, suggestions of several increasingly simple mechanical systems capable of self-reproduction were made — notably by Lionel Penrose.

Von Neumann's kinematic model

A detailed conceptual proposal for a self-replicating machine was first put forward by mathematician John von Neumann in lectures delivered in 1948 and 1949, when he proposed a kinematic model of self-reproducing automata as a thought experiment. Von Neumann's concept of a physical self-replicating machine was dealt with only abstractly, with the hypothetical machine using a "sea" or stockroom of spare parts as its source of raw materials. The machine had a program stored on a memory tape that directed it to retrieve parts from this "sea" using a manipulator, assemble them into a duplicate of itself, and then copy the contents of its memory tape into the empty duplicate's. The machine was envisioned as consisting of as few as eight different types of components; four logic elements that send and receive stimuli and four mechanical elements used to provide a structural skeleton and mobility. While qualitatively sound, von Neumann was evidently dissatisfied with this model of a self-replicating machine due to the difficulty of analyzing it with mathematical rigor. He went on to instead develop an even more abstract model self-replicator based on cellular automata. His original kinematic concept remained obscure until it was popularized in a 1955 issue of Scientific American.

Von Neumann's goal for his self-reproducing automata theory, as specified in his lectures at the University of Illinois in 1949, was to design a machine whose complexity could grow automatically akin to biological organisms under natural selection. He asked what is the threshold of complexity that must be crossed for machines to be able to evolve. His answer was to design an abstract machine which, when run, would replicate itself. Notably, his design implies that open-ended evolution requires inherited information to be copied and passed to offspring separately from the self-replicating machine, an insight that preceded the discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule by Watson and Crick and how it is separately translated and replicated in the cell.

Moore's artificial living plants

In 1956 mathematician Edward F. Moore proposed the first known suggestion for a practical real-world self-replicating machine, also published in Scientific American. Moore's "artificial living plants" were proposed as machines able to use air, water and soil as sources of raw materials and to draw its energy from sunlight via a solar battery or a steam engine. He chose the seashore as an initial habitat for such machines, giving them easy access to the chemicals in seawater, and suggested that later generations of the machine could be designed to float freely on the ocean's surface as self-replicating factory barges or to be placed in barren desert terrain that was otherwise useless for industrial purposes. The self-replicators would be "harvested" for their component parts, to be used by humanity in other non-replicating machines.

Dyson's replicating systems

The next major development of the concept of self-replicating machines was a series of thought experiments proposed by physicist Freeman Dyson in his 1970 Vanuxem Lecture. He proposed three large-scale applications of machine replicators. First was to send a self-replicating system to Saturn's moon Enceladus, which in addition to producing copies of itself would also be programmed to manufacture and launch solar sail-propelled cargo spacecraft. These spacecraft would carry blocks of Enceladean ice to Mars, where they would be used to terraform the planet. His second proposal was a solar-powered factory system designed for a terrestrial desert environment, and his third was an "industrial development kit" based on this replicator that could be sold to developing countries to provide them with as much industrial capacity as desired. When Dyson revised and reprinted his lecture in 1979 he added proposals for a modified version of Moore's seagoing artificial living plants that was designed to distill and store fresh water for human use and the "Astrochicken."

Advanced Automation for Space Missions

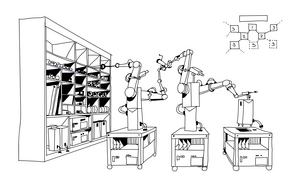

In 1980, inspired by a 1979 "New Directions Workshop" held at Wood's Hole, NASA conducted a joint summer study with ASEE entitled Advanced Automation for Space Missions to produce a detailed proposal for self-replicating factories to develop lunar resources without requiring additional launches or human workers on-site. The study was conducted at Santa Clara University and ran from June 23 to August 29, with the final report published in 1982. The proposed system would have been capable of exponentially increasing productive capacity and the design could be modified to build self-replicating probes to explore the galaxy.

The reference design included small computer-controlled electric carts running on rails inside the factory, mobile "paving machines" that used large parabolic mirrors to focus sunlight on lunar regolith to melt and sinter it into a hard surface suitable for building on, and robotic front-end loaders for strip mining. Raw lunar regolith would be refined by a variety of techniques, primarily hydrofluoric acid leaching. Large transports with a variety of manipulator arms and tools were proposed as the constructors that would put together new factories from parts and assemblies produced by its parent.

Power would be provided by a "canopy" of solar cells supported on pillars. The other machinery would be placed under the canopy.

A "casting robot" would use sculpting tools and templates to make plaster molds. Plaster was selected because the molds are easy to make, can make precise parts with good surface finishes, and the plaster can be easily recycled afterward using an oven to bake the water back out. The robot would then cast most of the parts either from nonconductive molten rock (basalt) or purified metals. A carbon dioxide laser cutting and welding system was also included.

A more speculative, more complex microchip fabricator was specified to produce the computer and electronic systems, but the designers also said that it might prove practical to ship the chips from Earth as if they were "vitamins."

A 2004 study supported by NASA's Institute for Advanced Concepts took this idea further. Some experts are beginning to consider self-replicating machines for asteroid mining.

Much of the design study was concerned with a simple, flexible chemical system for processing the ores, and the differences between the ratio of elements needed by the replicator, and the ratios available in lunar regolith. The element that most limited the growth rate was chlorine, needed to process regolith for aluminium. Chlorine is very rare in lunar regolith.

Lackner-Wendt Auxon replicators

In 1995, inspired by Dyson's 1970 suggestion of seeding uninhabited deserts on Earth with self-replicating machines for industrial development, Klaus Lackner and Christopher Wendt developed a more detailed outline for such a system. They proposed a colony of cooperating mobile robots 10–30 cm in size running on a grid of electrified ceramic tracks around stationary manufacturing equipment and fields of solar cells. Their proposal didn't include a complete analysis of the system's material requirements, but described a novel method for extracting the ten most common chemical elements found in raw desert topsoil (Na, Fe, Mg, Si, Ca, Ti, Al, C, O2 and H2) using a high-temperature carbothermic process. This proposal was popularized in Discover magazine, featuring solar-powered desalination equipment used to irrigate the desert in which the system was based. They named their machines "Auxons", from the Greek word auxein which means "to grow".

Recent work

NIAC studies on self-replicating systems

In the spirit of the 1980 "Advanced Automation for Space Missions" study, the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts began several studies of self-replicating system design in 2002 and 2003. Four phase I grants were awarded:

- Hod Lipson (Cornell University), "Autonomous Self-Extending Machines for Accelerating Space Exploration"

- Gregory Chirikjian (Johns Hopkins University), "Architecture for Unmanned Self-Replicating Lunar Factories"

- Paul Todd (Space Hardware Optimization Technology Inc.), "Robotic Lunar Ecopoiesis"

- Tihamer Toth-Fejel (General Dynamics), "Modeling Kinematic Cellular Automata: An Approach to Self-Replication" The study concluded that complexity of the development was equal to that of a Pentium 4, and promoted a design based on cellular automata.

Bootstrapping self-replicating factories in space

In 2012, NASA researchers Metzger, Muscatello, Mueller, and Mantovani argued for a so-called "bootstrapping approach" to start self-replicating factories in space. They developed this concept on the basis of In Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) technologies that NASA has been developing to "live off the land" on the Moon or Mars. Their modeling showed that in just 20 to 40 years this industry could become self-sufficient then grow to large size, enabling greater exploration in space as well as providing benefits back to Earth. In 2014, Thomas Kalil of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy published on the White House blog an interview with Metzger on bootstrapping solar system civilization through self-replicating space industry. Kalil requested the public submit ideas for how "the Administration, the private sector, philanthropists, the research community, and storytellers can further these goals." Kalil connected this concept to what former NASA Chief technologist Mason Peck has dubbed "Massless Exploration", the ability to make everything in space so that you do not need to launch it from Earth. Peck has said, "...all the mass we need to explore the solar system is already in space. It's just in the wrong shape." In 2016, Metzger argued that fully self-replicating industry can be started over several decades by astronauts at a lunar outpost for a total cost (outpost plus starting the industry) of about a third of the space budgets of the International Space Station partner nations, and that this industry would solve Earth's energy and environmental problems in addition to providing massless exploration.

New York University artificial DNA tile motifs

In 2011, a team of scientists at New York University created a structure called 'BTX' (bent triple helix) based around three double helix molecules, each made from a short strand of DNA. Treating each group of three double-helices as a code letter, they can (in principle) build up self-replicating structures that encode large quantities of information.

Self-replication of magnetic polymers

In 2001, Jarle Breivik at University of Oslo created a system of magnetic building blocks, which in response to temperature fluctuations, spontaneously form self-replicating polymers.

Self-replication of neural circuits

In 1968, Zellig Harris wrote that "the metalanguage is in the language," suggesting that self-replication is part of language. In 1977 Niklaus Wirth formalized this proposition by publishing a self-replicating deterministic context-free grammar. Adding to it probabilities, Bertrand du Castel published in 2015 a self-replicating stochastic grammar and presented a mapping of that grammar to neural networks, thereby presenting a model for a self-replicating neural circuit.

Harvard Wyss Institute

November 29, 2021 a team at Harvard Wyss Institute built the first living robots that can reproduce.

Self-replicating spacecraft

The idea of an automated spacecraft capable of constructing copies of itself was first proposed in scientific literature in 1974 by Michael A. Arbib, but the concept had appeared earlier in science fiction such as the 1967 novel Berserker by Fred Saberhagen or the 1950 novellette trilogy The Voyage of the Space Beagle by A. E. van Vogt. The first quantitative engineering analysis of a self-replicating spacecraft was published in 1980 by Robert Freitas, in which the non-replicating Project Daedalus design was modified to include all subsystems necessary for self-replication. The design's strategy was to use the probe to deliver a "seed" factory with a mass of about 443 tons to a distant site, have the seed factory replicate many copies of itself there to increase its total manufacturing capacity, and then use the resulting automated industrial complex to construct more probes with a single seed factory on board each.

Prospects for implementation

As the use of industrial automation has expanded over time, some factories have begun to approach a semblance of self-sufficiency that is suggestive of self-replicating machines. However, such factories are unlikely to achieve "full closure" until the cost and flexibility of automated machinery comes close to that of human labour and the manufacture of spare parts and other components locally becomes more economical than transporting them from elsewhere. As Samuel Butler has pointed out in Erewhon, replication of partially closed universal machine tool factories is already possible. Since safety is a primary goal of all legislative consideration of regulation of such development, future development efforts may be limited to systems which lack either control, matter, or energy closure. Fully capable machine replicators are most useful for developing resources in dangerous environments which are not easily reached by existing transportation systems (such as outer space).

An artificial replicator can be considered to be a form of artificial life. Depending on its design, it might be subject to evolution over an extended period of time. However, with robust error correction, and the possibility of external intervention, the common science fiction scenario of robotic life run amok will remain extremely unlikely for the foreseeable future.

Other sources

- A number of patents have been granted for self-replicating machine concepts. U.S. patent 5,659,477 "Self reproducing fundamental fabricating machines (F-Units)" Inventor: Collins; Charles M. (Burke, Va.) (August 1997), U.S. patent 5,764,518 " Self reproducing fundamental fabricating machine system" Inventor: Collins; Charles M. (Burke, Va.)(June 1998); and Collins' PCT patent WO 96/20453: "Method and system for self-replicating manufacturing stations" Inventors: Merkle; Ralph C. (Sunnyvale, Calif.), Parker; Eric G. (Wylie, Tex.), Skidmore; George D. (Plano, Tex.) (January 2003).

- Macroscopic replicators are mentioned briefly in the fourth chapter of K. Eric Drexler's 1986 book Engines of Creation.

- In 1995, Nick Szabo proposed a challenge to build a macroscale replicator from Lego robot kits and similar basic parts. Szabo wrote that this approach was easier than previous proposals for macroscale replicators, but successfully predicted that even this method would not lead to a macroscale replicator within ten years.

- In 2004, Robert Freitas and Ralph Merkle published the first comprehensive review of the field of self-replication (from which much of the material in this article is derived, with permission of the authors), in their book Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines, which includes 3000+ literature references. This book included a new molecular assembler design, a primer on the mathematics of replication, and the first comprehensive analysis of the entire replicator design space.