Ego death is a "complete loss of subjective self-identity".[1] The term is used in various intertwined contexts, with related meanings. In Jungian psychology, the synonymous term psychic death is used, which refers to a fundamental transformation of the psyche.[2] In death and rebirth mythology, ego death is a phase of self-surrender and transition,[3][4][5][6] as described by Joseph Campbell in his research on the mythology of the Hero's Journey.[3] It is a recurrent theme in world mythology and is also used as a metaphor in some strands of contemporary western thinking.[6]

In descriptions of psychedelic experiences, the term is used synonymously with ego-loss[7][8][1][9] to refer to (temporary) loss of one's sense of self due to the use of psychedelics.[10][11][1] The term was used as such by Timothy Leary et al.[1] to describe the death of the ego[12] in the first phase of an LSD trip, in which a "complete transcendence" of the self[note 1] and the "game"[note 2] occurs.[13] The concept is also used in contemporary spirituality and in the modern understanding of eastern religions to describe a permanent loss of "attachment to a separate sense of self"[web 1] and self-centeredness.[14] This conception is an influential part of Jiddu Krishnamurti and Eckhart Tolle's teachings, where Ego is presented as an accumulation of thoughts and emotions, continuously identified with, which creates the idea and feeling of being a separate entity, and only by disidentifying one’s consciousness from it can one truly be free from suffering (in the Buddhist meaning).[15]

Definitions

Ego death and the related term "ego loss" have been defined in the context of mysticism by the religious studies scholar Daniel Mekur as "an imageless experience in which there is no sense of personal identity. It is the experience that remains possible in a state of extremely deep trance when the ego-functions of reality-testing, sense-perception, memory, reason, fantasy and self-representation are repressed [...] Muslim Sufis call it fana (annihilation),[note 3] and medieval Jewish kabbalists termed it "the kiss of death".[16]Carter Phipps equates Enlightenment and ego death, which he defines as "the renunciation, rejection and, ultimately, the death of the need to hold on to a separate, self-centered existence.[17][note 4]

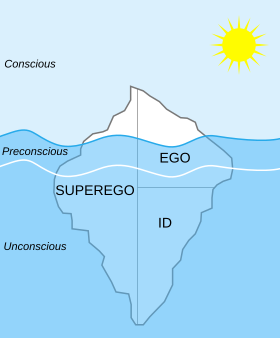

In Jungian psychology, Ventegodt and Merrick define ego death as "a fundamental transformation of the psyche. Such a shift in personality has been labeled an "ego death" in Buddhism or a psychic death by Jung.[19]

In comparative mythology, Ego death is the second phase of Joseph Campbell's description of The Hero's Journey, which includes a phase of separation, transition, and incorporation.[6] The second phase is a phase of self-surrender and ego-death, where-after the hero returns to enrich the world with his discoveries.[4][5][6][3]

In psychedelic culture, Leary, Metzer & Alpert (1964) define ego death, or ego loss as they call it, as part of the (symbolic) experience of death in which the old ego must die before one can be spiritually reborn.[13] They define Ego loss as "... complete transcendence − beyond words, beyond space−time, beyond self. There are no visions, no sense of self, no thoughts. There are only pure awareness and ecstatic freedom". [13] [20]

Several psychologists working on pschedelics have defined ego-death. Alnaes (1964) defines ego-death as "[L]oss of ego-feeling."[10]}}. Stanislav Grof (1988) defines it as "a sense of total annihilation [...] This experience of ego death seems to entail an instant merciless destruction of all previous reference points in the life of the individual [...] [E]go death means an irreversible end to one's philosophical identification with what Alan Watts called skin-encapsulated ego.[21] The psychologist John Harrison (2010) defines "[T]emporary ego death [as the] loss of the separate self[,] or, in the affirmative, [...] a deep and profound merging with the transcendent other.[11] Johnson, Richards & Griffiths (2008), paraphrasing Leary et al. and Grof: define ego death as "temporarily experienc[ing] a complete loss of subjective self-identity.[1]

Conceptual development

The concept of "ego death" developed along a number of intertwined strands of thought, especially romantic movements[22] and subcultures,[23] Theosophy,[24] anthropological research on rites de passage[25] and shamanism[23] Joseph Campbell's comparative mythology,[4][5][6][3] Jungian psychology,[26][3] the psychedelic scene of the 1960s,[27] and transpersonal psychology.[28]Western mysticism

According to Merkur,The conceptualisation of mystical union as the soul's death, and its replacement by God's consciousness, has been a standard Roman Catholic trope since St. Teresa of Ávila; the motif traces back through Marguerite Porete, in the 13th century, to the fana,[note 3] "annihilation", of the Islamic Sufis.[29]

Jungian psychology

According to Ventegodt and Merrick, the Jungian term "psychic death" is a synonym for "ego death":In order to radically improve global quality of life, it seems necessary to have a fundamental transformation of the psyche. Such a shift in personality has been labeled an "ego death" in Buddhism or a psychic death by Jung, because it implies a shift back to the existential position of the natural self, i.e., living the true purpose of life. The problem of healing and improving the global quality of life seems strongly connected to the unpleasantness of the ego-death experience.[19]Ventegodt and Merrick refer to Jung's publications The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, first published 1933, and Psychology and Alchemy, first published in 1944.[19][note 5]

In Jungian psychology, a unification of archetypal opposites has to be reached, during a process of conscious suffering, in which consciousness "dies" and resurrects. Jung called this process "the transcendent function",[note 6] which leads to a "more inclusive and synthetic consciousness".[30]

Jung used analogies with alchemy to describe the individuation process, and the transference-processes which occur during therapy.[31]

According to Leeming et al., from a religious point of view psychic death is related to St. John of the Cross' Ascent of Mt. Carmel and Dark Night of the Soul.[32]

Mythology – The Hero with a Thousand Faces

The Hero's Journey

In 1949, Joseph Campbell published The Hero with a Thousand Faces, a study on the archetype of the Hero's Journey.[3] It describes a common theme found in many cultures worldwide,[3] and is also described in many contemporary theories on personal transformation.[6] In traditional cultures it describes the "wilderness passage",[3] the transition from adolescence into adulthood.[25] It typically includes a phase of separation, transition, and incorporation.[6] The second phase is a phase of self-surrender and ego-death, whereafter the hero returns to enrich the world with their discoveries. Campbell describes the basic theme as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.[33]This journey is based on the archetype of death and rebirth,[5] in which the "false self" is surrendered and the "true self" emerges.[5] A well known example is Dante's Divina Comedia, in which the hero descends into the underworld.[5]

Psychedelics

Concepts and ideas from mysticism and bohemianism were inherited by the Beat Generation.[22] When Aldous Huxley helped popularize the use of psychedelics, starting with The Doors of Perception, published in 1954, [34] Huxley also promoted a set of analogies with eastern religions, as described in The Perennial Philosophy. This book helped inspire the 1960s belief in a revolution in western consciousness [34] and included the Tibetan Book of the Dead was one of the sources.[34] Similarly, Alan Watts, in his opening statement on mystical experiences in This Is It, draws parallels with Richard Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness, describing the "central core" of the experience as... the conviction, or insight, that the immediate now, whatever its nature, is the goal and fulfillment of all living.[35]This interest in mysticism helped shape the emerging research and popular conversation around psychedelics in the 1960s.[36] In 1964 William S. Burroughs drew a distinction between "sedative" and "conscious-expanding" drugs.[37] In the 1940s and 1950s the use of LSD was restricted to military and psychiatric researchers. One of those researchers was Timothy Leary, a clinical psychologist who first encountered psychedelic drugs while on vacation in 1960,[38] and started to research the effects of psilocybin in 1961.[34] He sought advice from Aldous Huxley, who advised him to propagate psychedelic drugs among society's elites, including artists and intellectuals.[38] On insistence of Allen Ginsberg, Leary, together with his younger colleague Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) also made LSD available to students.[38] In 1962 Leary was fired, and Harvard's psychedelic research program was shut down.[38] In 1962 Leary founded the Castalia Foundation,[38] and in 1963 he and his colleagues founded the journal The Psychedelic Review.[39]

Following Huxley's advice, Leary wrote a manual for LSD-usage.[39] The Psychedelic Experience, published in 1964, is a guide for LSD-trips, written by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert, loosely based on Yvan-Wentz's translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead.[39][34] Aldous Huxley introduced the Tibetan Book of the Dead to Timothy Leary.[34] According to Leary, Metzer and Alpert, the Tibetan Book of the Dead is

... a key to the innermost recesses of the human mind, and a guide for initiates, and for those who are seeking the spiritual path of liberation.[40]They construed the effect of LSD as a "stripping away" of ego-defenses, finding parallels between the stages of death and rebirth in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and the stages of psychological "death" and "rebirth" which Leary had identified during his research.[41] According to Leary, Metzer and Alpert it is....

... one of the oldest and most universal practices for the initiate to go through the experience of death before he can be spiritually reborn. Symbolically he must die to his past, and to his old ego, before he can take his place in the new spiritual life into which he has been initiated.[12]Also in 1964 Randolf Alnaes published "Therapeutic applications of the change in consciousness produced by psycholytica (LSD, Psilocybin, etc.)."[42][10] Alnaes notes that patients may become involved in existential problems as a consequence of the LSD experience. Psycholytic drugs may facilitate insight. With a short psychological treatment, patients may benefit from changes brought about by the effects of the experience.[42]

One of the LSD-experiences may be the death crisis. Alnaes discernes three stages in this kind of experience:[10]

- Psychosomatic symptoms lead up to the "loss of ego feeling (ego death)";[10]

- A sense of separation of the observing subject from the body. The body is beheld to undergo death or an associated event;

- "Rebirth", the return to normal, conscious mentation, "characteristically involving a tremendous sense of relief, which is cathartic in nature and may lead to insight".[10]

Leary's description of "Ego-death"

In The Psychedelic Experience, three stages are discerned:- Chikhai Bardo: ego loss, a "complete transcendence" of the self[note 1] and game;[13][note 2]

- Chonyid Bardo: The Period of Hallucinations;[43]

- Sidpa Bardo: the return to routine game reality and the self.[13]

O (name of voyager)

The time has come for you to seek new levels of reality.

Your ego and the (name) game are about to cease.

You are about to be set face to face with the Clear Light

You are about to experience it in its reality.

In the ego−free state, wherein all things are like the void and cloudless sky,

And the naked spotless intellect is like a transparent vacuum;

At this moment, know yourself and abide in that state.

O (name of voyager),

That which is called ego−death is coming to you.

Remember:

This is now the hour of death and rebirth;

Take advantage of this temporary death to obtain the perfect state −

Enlightenment.

. . .[44]

Scientific Research

Stanislav Grof

Stanislav Grof has researched the effects of psychedelic substances,[45] which can also be induced by nonpharmacological means.[46] Grof has developed a "cartography of the psyche" based on his clinical work with psychedelics,[47] which describe the "basic types of experience that become available to an average person" when using psychedelics or "various powerful non-pharmacological experiential techniques".[48]According to Grof, traditional psychiatry, psychology and psychotherapy use a model of the human personality that is limited to biography and the individual consciousness, as described by Freud.[49] This model is inadequate to describe the experiences which result from the use of psychedelics and the use of "powerful techniques", which activate and mobilize "deep unconscious and superconscious levels of the human psyche".[49] These levels include:[28]

- The Sensory Barrier and the Recollective-Biographical Barrier

- The Perinatal Matrices:

- BPM I: The Amniotic Universe. Maternal womb; symbiotic unity of the fetus with the maternal organism; lack of boundaries and obstructions;

- BPM II: Cosmic Engulfment and No Exit. Onset of labor; alteration of blissful connection with the mother and its pristine universe;

- BPM III: The Death-Rebirth Struggle. Movement through the birth channel and struggle for survival;

- BPM IV: The Death-Rebirth Experience. Birth and release.

- The Transpersonal Dimensions of the Psyche

This experience of ego death seems to entail an instant merciless destruction of all previous reference points in the life of the individual.[21]According to Grof what dies in this process is "a basically paranoid attitude toward the world which reflects the negative experience of the subject during childbirth and later".[21] When experienced in its final and most complete form,

...ego death means an irreversible end to one's philosophical identification with what Alan Watts called skin-encapsulated ego."[21]

Recent research

Recent research also mentions that ego loss is sometimes experienced by those under the influence of psychedelic drugs.[51]The Ego-Dissolution Inventory is a validated self-report questionnaire that allows for the measurement of transient ego-dissolution experiences occasioned by psychedelic drugs. [52]

View of Spiritual Traditions

Following the interest in psychedelics and spirituality, the term "ego death" has been used to describe the eastern notion of "enlightenment" (bodhi) or moksha.Buddhism

Zen practice is said to lead to ego-death.[53] Ego-death is also called "great death", in contrast to the physical "small death".[54] According to Jin Y. Park, the ego death that Buddhism encourages makes an end to the "usually-unconsciousness-and-automated quest" to understand the sense-of-self as a thing, instead of as a process.[55] According to Park, meditation is learning how to die by learning to "forget" the sense of self:[55]Enlightenment occurs when the usually automatized reflexivity of consciousness ceases, which is experienced as a letting-go and falling into the void and being wiped out of existence [...] [W]hen consciousness stops trying to catch its own tail, I become nothing, and discover that I am everything.[56]According to Welwood, "egolessness" is a common experience. Egolessness appears "in the gaps and spaces between thoughts, which usually go unnoticed".[57] Existential anxiety arises when one realizes that the feeling of "I" is nothing more than a perception. According to Welwood, only egoless awareness allows us to face and accept death in all forms.[57]

David Loy also mentions the fear of death,[58] and the need to undergo ego-death to realize our true nature.[59][60] According to Loy, our fear of egolessness may even be stronger than our fear of death.[58]

"Egolessness" is not the same as anatta, non-self. Anatta means not to take the constituents of the person as a permanent entity:

the Buddha, almost ad nauseam, spoke against wrong identification with the Five Aggregates, or the same, wrong identification with the psychophysical believing it is our self. These aggregates of form, feeling, thought, inclination, and sensory consciousness, he went on to say, were illusory; they belonged to Mara the Evil One; they were impermanent and painful. And for these reasons, the aggregates cannot be our self. [web 2]

Bernadette Roberts

Bernadette Roberts makes a distinction between "no ego" and "no self".[61][62] According to Roberts, the falling away of the ego is not the same as the falling away of the self.[63] "No ego" comes prior to the unitive state; with the falling away of the unitive state comes "no self".[64] "Ego" is defined by Roberts as... the immature self or consciousness prior to the falling away of its self-center and the revelation of a divine center.[65]Roberts defines "self" as

... the totality of consciousness, the entire human dimension of knowing, feeling and experiencing from the consciousness and unconsciousness to the unitive, transcendental or God-consciousness.[65]Ultimately, all experiences on which these definitions are based are wiped out or dissolved.[65] Jeff Shore further explains that "no self" means "the permanent ceasing, the falling away once and for all, of the entire mechanism of reflective self-consciousness".[66]

According to Roberts, both the Buddha and Christ embody the falling away of self, and the state of "no self". The falling away is represented by the Buddha prior to his enlightenment, starving himself by ascetic practices, and by the dying Jesus on the cross; the state of "no self" is represented by the enlightened Buddha with his serenity, and by the resurrected Christ.[65]

Integration after Ego-death experiences

Psychedelics

According to Nick Bromell, ego death is a tempering though frightening experience, which may lead to a reconciliation with the insight that there is no real self.[67]According to Grof, death crises may occur over a series of psychedelic sessions until they cease to lead to panic. A conscious effort not to panic may lead to a "pseudohallucinatory sense of transcending physical death".[10] According to Merkur,

Repeated experience of the death crisis and its confrontation with the idea of physical death leads finally to an acceptance of personal mortality, without further illusions. The death crisis is then greeted with equanimity.[10]

Vedanta and Zen

Both the Vedanta and the Zen-Buddhist tradition warn that insight into the emptiness of the self, or so-called "enlightenment experiences", are not sufficient; further practice is necessary.Jacobs warns that Advaita Vedanta practice takes years of committed practice to sever the "occlusion"[68] of the so-called "vasanas, samskaras, bodily sheaths and vrittis", and the "granthi[note 7] or knot forming identification between Self and mind".[69]

Zen Buddhist training does not end with kenshō, or insight into one's true nature. Practice is to be continued to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life.[70][71][72][73] According to Hakuin, the main aim of "post-satori practice"[74][75] (gogo no shugyo[76] or kojo, "going beyond"[77]) is to cultivate the "Mind of Enlightenment".[78] According to Yamada Koun, "if you cannot weep with a person who is crying, there is no kensho".[79]

Dark Night and depersonalisation

Shinzen Young, an American Buddhist teacher, has pointed at the difficulty integrating the experience of no self. He calls this "the Dark Night", or... "falling into the Pit of the Void." It entails an authentic and irreversible insight into Emptiness and No Self. What makes it problematic is that the person interprets it as a bad trip. Instead of being empowering and fulfilling, the way Buddhist literature claims it will be, it turns into the opposite. In a sense, it's Enlightenment's Evil Twin.[web 3]Willoughby Britton is conducting research on such phenomena which may occur during meditation, in a research program called "The Dark Night of the Soul".[web 4] She has searched texts from various traditions to find descriptions of difficult periods on the spiritual path,[web 5] and conducted interviews to find out more on the difficult sides of meditation.[web 4][note 8]

Influence

The propagation of LSD-induced "mystical experiences", and the concept of ego death, had some influence in the 1960s, but Leary's brand of LSD-spirituality never "quite caught on".[80]Reports of psychedelic experiences

Leary's terminology influenced the understanding and description of the effects of psychedelics. Various reports by hippies of their psychedelic experiences describe states of diminished consciousness which were labelled as "ego death", but do not match Leary's descriptions.[81] Panic attacks were occasionally also labeled as "ego death".[82]The Beatles

John Lennon read The Psychedelic Experience, and was strongly affected by it.[83] He wrote "Tomorrow Never Knows" after reading the book, as a guide for his LSD-trips.[83] Lennon took about a thousand acid-trips, but it only exacerbated his personal difficulties.[84] He eventually stopped using the drug. George Harrison and Paul McCartney also concluded that LSD use didn't result in any worthwhile changes.[85]Radical pluralism

According to Bromell, the experience of ego death confirms a radical pluralism that most people experience in their youth, but prefer to flee from, instead believing in a stable self and a fixed reality.[86] He further states this also led to a different attitude among youngsters in the 1960s, rejecting the lifestyle of their parents as being deceitful and false.[86]Criticisms of ego death

The relationship between ego death and LSD has been disputed. Hunter S. Thompson, who tried LSD,[87] saw a self-centered base in Leary's work, noting that Leary placed himself at the centre of his texts, using his persona as "an exemplary ego, not a dissolved one". [87] Dan Merkur notes that the use of LSD in combination with Leary's manual often did not lead to ego-death, but to horrifying bad trips.[88]The relationship between LSD use and enlightenment has also been criticized. Sōtō-Zen teacher Brad Warner has repeatedly criticized the idea that psychedelic experiences lead to "enlightenment experiences".[note 9] In response to The Psychedelic Experience he wrote:

While I was at Starwood, I was getting mightily annoyed by all the people out there who were deluding themselves and others into believing that a cheap dose of acid, 'shrooms, peyote, "molly" or whatever was going to get them to a higher spiritual plane [...] While I was at that campsite I sat and read most of the book The Psychedelic Experience by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (aka Baba Ram Dass, later of Be Here Now fame). It's a book about the authors' deeply mistaken reading of the Tibetan Book of the Dead as a guide for the drug taking experience [...] It was one thing to believe in 1964 that a brave new tripped out age was about to dawn. It's quite another to still believe that now, having seen what the last 47 years have shown us about where that path leads. If you want some examples, how about Jimi Hendrix, Sid Vicious, Syd Barrett, John Entwistle, Kurt Cobain... Do I really need to get so cliched with this? Come on now.[web 6]The concept that ego-death or a similar experience might be considered a common basis for religion has been disputed by scholars in religious studies [89] but "has lost none of its popularity".[90] Scholars have also criticized Leary and Albert's attempt to tie ego-death and psychedelics with Tibetan Buddhism. John Myrdhin Reynolds, has disputed Leary and Jung's use of the Evans-Wentz's translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, arguing that it introduces a number of misunderstandings about Dzogchen.[91] Reynolds argues that Evans-Wentz's was not familiar with Tibetan Buddhism,[91] and that his view of Tibetan Buddhism was "fundamentally neither Tibetan nor Buddhist, but Theosophical and Vedantist".[92] Nonetheless, Reynolds confirms that the nonsubstantiality of the ego is the ultimate goal of the Hinayana system .[93]