The

theoretical scenario of the clathrate gun hypothesis. Arctic methane

emissions lead to warming and in turn to more dissociation.

The clathrate gun hypothesis or Methane time bomb

(now effectively disproved) is the name given to the idea that as sea

temperatures rise in the Arctic, this can trigger a strong positive feedback effect on climate. The hypothesis was that this warming would cause a sudden release of methane from methane clathrate compounds buried in seabeds and seabed permafrost, and then, because methane itself is a powerful greenhouse gas,

temperatures rise further, and the cycle repeats. The original idea was

that this runaway process, once started, could be as irreversible as

the firing of a gun. It originates from a paper by Kennett et al

published in 2003, which proposed that the "clathrate gun" could cause abrupt runaway warming on a time scale less than a human lifetime.

"Gun" suggests an exothermic reaction like an explosion. The

clathrate decomposition is endothermic - if some of the clathrates are

released they cool down the rest of the deposits. This means that the

only way it can happen explosively is by a feedback with Earth's climate

rapidly warming up the oceans.

The clathrates are not only kept stable by the low temperatures at

the sea bed. They are also kept stable by pressure of the depth of sea

above the deposits. The clathrates can slowly decompose as the result of

lowering sea levels during ice ages, or by the sea floor rising along

continental shelves when the ice resting on the land melts. This needs

to be distinguished from clathrate dissociation due to a warming sea,

which is needed for the clathrate gun hypothesis.

In December 2016, a major literature review by the 2107 USGS Hydrates

project concluded that evidence is lacking for the original hypothesis. In 2017, the Royal Society

review came to a similar conclusion that there is a relatively limited

role for climate feedback from dissociation of the methane clathrates.

The 2018 Annual Review of Environment and Resources on Methane and Global Environmental Change concluded that "Nevertheless,

it seems unlikely that catastrophic, widespread dissociation of marine

clathrates will be triggered by continued climate warming at

contemporary rates (0.2◦C per decade) during the twenty-first century".

In 2018, the CAGE research group (Centre for

Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate) came to a much stronger

conclusion when they published evidence that the methane clathrates

formed over 6 million years ago and have been slowly releasing methane

for 2 million years independent of warm or cold climate, rather than

releasing methane only recently as had previously been thought

.

At one time this hypothesis was thought to be responsible for warming events in and at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum around 26,500 years ago, but this is now also thought to be unlikely.

At one point it was thought that a much slower runaway methane

clathrate breakdown might have acted over longer timescales of tens of

thousands of years during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum 56 million years ago, and the Permian–Triassic extinction event, 252 million years ago. However, this is now thought unlikely.

To hear what an expert says about the topic, see #Video interview with Carolyn Ruppel (USGS Gas Hydrates Project) below.

Methane clathrates

Tetrakaidecahedral

Methane clathrate hydrate I, methane molecule consisting of one carbon

atom attached to four hydrogen atoms shown in the center surrounded by a

cage formed of water molecules

Methane clathrate, also known commonly as methane hydrate,

is a form of water ice that contains a large amount of methane within

its crystal structure, which is stable under pressure, and remains

stable under higher temperatures than ice, up to a few degrees above

0 °C depending on the pressure. .

The methane forms a structure I hydrate, trapped in dodecahedral

cages made up of water molecules which are kept stable by a methane

molecule inside each one. These are then each surrounded by tetrahedra

to form part of a larger lattice with tetrakeidecahedral cavities which also contain methane molecules. Potentially large deposits of methane clathrate have been found under sediments on the ocean floors of the Earth.

Methane is much more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon

dioxide, although it has a short atmospheric lifetime of around 12

years. Shindell et al(2009) calculated that it has a global warming potential, the ratio of its warming potential to that of CO2. of between 79 and 105 over 20 years, and between 25 and 40 over 100 years, after accounting for aerosol interactions.

How the clathrates dissociate

Gas-hydrate deposits by sector. Only those in sector 2 are likely to release methane that reaches the atmosphere

As the oceans warm then methane can be released as the methane

dissociates. The deposits extend to a depth of many meters and how much

of an effect this is depends on how far down into the deposits the

dissociation proceeds. The reaction absorbs heat rather than generating

it, so as the reaction proceeds it cools surrounding sediments rather

than warming them.

The 2017 and 2018 studies

have suggested only the topmost layers would be affected, while the

original hypothesis was based on the supposition that deep layers would

dissociate. The amount of the effect also depends on what happens to the

methane as it rises in the water column above it after it is released

from the clathrates. If the deposit is more than a hundred meters below

the surface then most of the methane in the bubbles dissolves into the

sea before it reaches the surface, since the sea is undersaturated in

methane.

At a density of around 0.9 g/cm3, methane hydrate will

float to the surface of the sea or of a lake unless it is bound in place

by being formed in or anchored to sediment. So the clathrate deposits

all consist of clathrates firmly bound within the ocean sediments.

USGS and Royal Society metastudies (2016 and 2017)

A USGS metastudy first published December 2016 by the USGS Gas Hydrates Project concluded:

"“Our review is the culmination of nearly a decade of original research by the USGS, my coauthor Professor John Kessler at the University of Rochester, and many other groups in the community,” said USGS geophysicist Carolyn Ruppel, who is the paper’s lead author and oversees the USGS Gas Hydrates Project. “After so many years spent determining where gas hydrates are breaking down and measuring methane flux at the sea-air interface, we suggest that conclusive evidence for release of hydrate-related methane to the atmosphere is lacking.”

From the Royal Society report:

"Clathrates: Some economic assessments continue to emphasize the potential damage from very strong and rapid methane hydrate release, although AR5 did not consider this likely. Recent measurements of methane fluxes from the Siberian Shelf Seas are much lower than those inferred previously. A range of other studies have suggested a much smaller influence of clathrate release on the Arctic atmosphere than had been suggested.

…. A recent modeling study joined earlier papers in assigning a relatively limited role to dissociation of methane hydrates as a climate feedback. Methane concentrations are rising globally, raising interesting questions (see section on methane) about what the cause is, finally new measurements of the 14C content of methane across the warming out of the last glacial period show that the release of old carbon reservoirs (including methane hydrates) played only a small role in the methane concentration increase that occurred then."

Timeline with original hypothesis, and later developments

This is a timeline of clathrates research with some of the milestones.

2007 - Most deposits are too deep, focus is on shallow deposits

Gas hydrate breakdown due to warming from ocean water

Most deposits of methane clathrate are in sediments too deep to respond rapidly, and modeling by Archer (2007) suggests the methane forcing should remain a minor component of the overall greenhouse effect. Clathrate deposits destabilize from the deepest part of their stability zone,

which is typically hundreds of meters below the seabed. A sustained

increase in sea temperature will warm its way through the sediment

eventually, and cause the shallowest, most marginal clathrate to start

to break down; but it will typically take on the order of a thousand

years or more for the temperature signal to get through.

Subsea permafrost occurs beneath the seabed and exists in the continental shelves of the polar regions. This source of methane is different from methane clathrates, but contributes to the overall outcome and feedbacks.

From sonar measurements in recent years researchers quantified the

density of bubbles emanating from subsea permafrost into the ocean (a

process called ebullition), and found that 100–630 mg methane per square

meter is emitted daily along the East Siberian Shelf, into the water

column. They also found that during storms, when wind accelerates

air-sea gas exchange, methane levels in the water column drop

dramatically. Observations suggest that methane release from seabed

permafrost will progress slowly, rather than abruptly. However, Arctic

cyclones, fueled by global warming,

and further accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere could

contribute to more rapid methane release from this source.

2008 - Original hypothesis, idea of a fast release of 50 gigatons of methane

Research

carried out in 2008 in the Siberian Arctic showed millions of tons of

methane being released, apparently through perforations in the seabed

permafrost, with concentrations in some regions reaching up to 100 times normal levels. The excess methane has been detected in localized hotspots in the outfall of the Lena River and the border between the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea.

At the time, some of the melting was thought to be the result of

geological heating, but more thawing was believed to be due to the

greatly increased volumes of meltwater being discharged from the

Siberian rivers flowing north. The current methane release had previously been estimated at 0.5 megatonnes per year.

Shakhova et al. (2008) estimate that not less than 1,400 gigatons of

carbon is presently locked up as methane and methane hydrates under the

Arctic submarine permafrost, and 5–10% of that area is subject to

puncturing by open taliks.

They conclude that "release of up to 50 gigatonnes of predicted amount

of hydrate storage [is] highly possible for abrupt release at any time".

That would increase the methane content of the planet's atmosphere by a

factor of twelve, equivalent in greenhouse effect to a doubling in the current level of CO2.

This is what lead to the original Clathrate gun hypothesis, and in

2008 the United States Department of Energy National Laboratory system

and the United States Geological Survey's Climate Change Science

Program both identified potential clathrate destabilization in the

Arctic as one of four most serious scenarios for abrupt climate change,

which have been singled out for priority research. The USCCSP released a

report in late December 2008 estimating the gravity of this risk.

2010 - Taliks or pongos could lead to gas migration pathways

There

is a possibility for the formation of gas migration pathways within

fault zones in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, through the process of talik formation, or pingo-like features.

2012 - Possible abrupt release of clathrates stabilized by low temperatures or after landslips

A 2012 assessment of the literature identifies methane hydrates on the Shelf of East Arctic Seas as a potential trigger.

The Arctic ocean

clathrates can exist in shallower water than elsewhere, stabilized by

lower temperatures rather than higher pressures; these may potentially

be marginally stable much closer to the surface of the sea-bed,

stabilized by a frozen 'lid' of permafrost preventing methane escape.

The so-called self-preservation phenomenon has been studied by Russian geologists starting in the late 1980s. This metastable clathrate state can be a basis for release events of methane excursions, such as during the interval of the Last Glacial Maximum. A study from 2010 concluded with the possibility for a trigger of abrupt climate warming based on metastable methane clathrates in the East Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS) region.

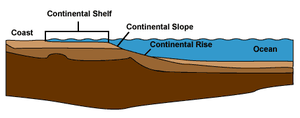

Profile illustrating the continental shelf, slope and rise

A trapped gas deposit on the continental slope off Canada in the Beaufort Sea,

located in an area of small conical hills on the ocean floor is just

290 meters below sea level and considered the shallowest known deposit

of methane hydrate.

Seismic

observation (in 2012) of destabilizing methane hydrate along the

continental slope of the eastern United States, following the intrusion

of warmer ocean currents, suggests that underwater landslides could

release methane. The estimated amount of methane hydrate in this slope

is 2.5 gigatonnes (about 0.2% of the amount required to cause the PETM),

and it is unclear if the methane could reach the atmosphere. However,

the authors of the study caution: "It is unlikely that the western North

Atlantic margin is the only area experiencing changing ocean currents;

our estimate of 2.5 gigatonnes of destabilizing methane hydrate may

therefore represent only a fraction of the methane hydrate currently

destabilizing globally."

2015 - Model based on the hypothesis suggests an extra 6 °C rise within 80 years

A study of the effects for the original hypothesis, based on a coupled climate–carbon cycle model (GCM)

assessed a 1000-fold (from <1 1000="" 25="" 6="" 80="" a="" amount="" and="" atmospheric="" based="" biosphere="" by="" carbon="" concluded="" critical="" decrease="" ecosystems="" especially="" estimates="" farming="" for="" from="" further="" gtc="" hydrates="" in="" increase="" it="" land="" less="" methane="" more="" nbsp="" on="" p="" petm="" ppmv="" pulse="" single="" situation="" stored="" suggesting="" temperatures="" than="" the="" to="" tropics.="" with="" within="" would="" years.="">

2016 Methane in upper continental slope clathrates doesn't get to surface

Some

of the shallow methane clathrates are indeed decomposing and there are

higher concentrations of methane near the sea floor that do indeed come

from the clathates. But it is taken up by the sea water and from the

measurements made by many scientists, almost none reaches the surface of

the sea. Methane in the upper layers of the sea do not come from the

sea floor and there aren't any significant atmospheric additions.

This is also the date of publication of the USGS metastudy

2017 - Fertilizing effect of methane at continental margins may lead to net CO2 sink

One paper published in 2017 found from measurements on the Svalbard margin that CO2

sequestration due to the fertilizing effect of the methane on surface

microbes lead to a net negative effect on radiative forcing, 231 times

greater than the effect of the methane emissions:

Continuous sea−air gas flux data collected over a shallow ebullitive methane seep field on the Svalbard margin reveal atmospheric CO2 uptake rates (−33,300±7,900 μmol m−2·d−1) twice that ofsurrounding waters and ∼1,900 times greater than the diffusive sea−air methane efflux (17.3±4.8μmol m−2·d−1). The negative radiative forcing expected from this CO2 uptake is up to 231 times greater than the positive radiative forcing from the methane emissions

2017 - Methane clathrates only decompose to a depth of 1.6 meters

However, later research cast doubt on this picture. Hong et al (2017)

studied the seepage from large mounds of hydrates in the shallow arctic

seas at Storfjordrenna, in the Barents Sea close to Svalbard. They

showed that though the temperature of the sea bed has fluctuated

seasonally over the last century, between 1.8 and 4.8 °C, it has only

affected release of methane to a depth of about 1.6 meters. The areas

that do destabilize do so only very slowly (centuries) because they are

only warmed sufficiently for less than half the year, from April to

August - and this doesn’t seem to be enough for fast destabilizing.

Hydrates can be stable through the top 60 meters of the sediments and

the current rapid releases came from deeper below the sea floor. They

concluded that the increase in flux started hundreds to thousands of

years ago well before the onset of warming that others speculated as its

cause, and that these seepages are not increasing due to momentary

warming. Summarizing his research, Hong stated:

"The results of our study indicate that the immense seeping found in this area is a result of natural state of the system. Understanding how methane interacts with other important geological, chemical and biological processes in the Earth system is essential and should be the emphasis of our scientific community,"

Further research by Klaus Wallmann et al (2018) found that the

hydrate release is due to the rebound of the sea bed after the ice

melted. The methane dissociation began around 8,000 years ago when the

land began to rise faster than the sea level, and the water as a result

started to get shallower with less hydrostatic pressure. This

dissociation therefore was a result of the uplift of the sea bed rather

than anthropogenic warming. The amount of methane released by the

hydrate dissociation was small. They found that the methane seeps

originate not from the hydrates but from deep geological gas reservoirs

(seepage from these formed the hydrates originally). They concluded that

the hydrates acted as a dynamic seal regulating the methane emissions

from the deep geological gas reservoirs and when they were dissociated

8,000 years ago, weakening the seal, this led to the higher methane

release still observed today.

This is also the date of publication of the Royal Society metastudy

2018 - CAGE group findings, the methane has been escaping at the same rate for millions of years

Research by the CAGE group in 2018 showed that the methane there has been escaping at the same rate for millions of years:

Recent observations of extensive methane release from the seafloor into the ocean and atmosphere cause concern as to whether increasing air temperatures across the Arctic are causing rapid melting of natural methane hydrates. Other studies, however, indicate that methane flares released in the Arctic today were created by processes that began way back in time – during the last Ice Age.

Newest research from the Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Climate and Environment (CAGE) shows that methane has been leaking in the Arctic for millions of years, independent of warm or cold climate. Methane has been forming in organic carbon rich sediments below the leakage spots off the coast of western Svalbard for a period of about 6 million years (since the late Miocene). According to our models, methane flares occurred at the seafloor for the first time at around 2 million years ago; at the exact time when ice sheets started to expand in the Arctic.

The acceleration of leakage occurred when the ice sheets were big enough to erode and deliver huge amounts of sediments towards the continental slope. Methane leakage was promoted due to formation of natural gas in organic-rich sediments under heavy loads of glacial sediments. Faults and fractures opened within the Earth’s crust as a consequence of growth and decay of the massive ice masses. This brought up the gases from deeper sediments higher up towards the seafloor. These gases then fueled the gas hydrate system off the Svalbard coast for the past 2 million years. It is, to this day, controlling the leakage of methane from the seabed.

So, the methane deposits formed in the late Miocene starting 6

million years ago, and the methane leaks have been going on for two

million years through multiple ice ages.

Also published in 2018, the Review of Environment and Resources on Methane and Global Environmental Change concluded that

"Although the clathrate gun hypothesis remains controversial (21), a good understanding of how environmental change affects natural CH4 sources is vital in terms of robustly projecting future fluxes under a changing climate."

Then later:

"Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that catastrophic, widespread dissociation of marine clathrates will be triggered by continued climate warming at contemporary rates (0.2◦C per decade) during the twenty-first century"

They did however urge caution about extraction of methane clathrates as a fuel, as this could lead to leaks of methane.

As discussed previously(Section 4.1), the stability of CH4 clathrate deposits may already be at risk from climate change.Accidental or deliberate disturbance, due to fossil fuel extraction, has the potential for extremelyhigh fugitive CH4 losses to the atmosphere

Past mass extinction events

At

one point it was thought that runaway methane clathrate breakdown might

also have acted over longer timescales of tens of thousands of years

during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum 56 million years ago, and most notably the Permian–Triassic extinction event,

when up to 96% of all marine species became extinct, 252 million years

ago. It was thought to have caused drastic alteration of the ocean

environment (such as ocean acidification and ocean stratification) and of the atmosphere.

However, the pattern of isotope shifts expected to result from a

massive release of methane does not match the patterns seen there.

First, the isotope shift is too large for this hypothesis, as it would

require five times as much methane as is postulated for the PETM, and then, it would have to be reburied at an unrealistically high rate to account for the rapid increases in the 13C/12C ratio throughout the early Triassic before it was released again several times.

One of the hypotheses being considered in its place is that the

temperature increase of the PETM was due to the roasting of carbonate

sediments such as coal beds by volcanism. Potentially this may have

released more than 3 trillion tons of carbon.

Effects thousands of years into our future

Although

significant effects are effectively ruled out at present, the oceans

would continue to warm by several degrees under the "Business as usual"

scenario. This would lead to the clathrates warming and eventually

dissociating, and some of this could contribute to the long tail of CO2,

helping to keep CO2 levels in the atmosphere higher for longer, as it

gradually is removed from the atmosphere by natural processes. David

Archer, author of many papers on gas hydrates, put it like this:

On the other hand, the deep ocean could ultimately (after a thousand years or so) warm up by several degrees in a business-as-usual scenario, which would make it warmer than it has been in millions of years. Since it takes millions of years to grow the hydrates, they have had time to grow in response to Earth’s relative cold of the past 10 million years or so. Also, the climate forcing from CO2 release is stronger now than it was millions of years ago when CO2 levels were higher, because of the band saturation effect of CO2 as a greenhouse gas. In short, if there was ever a good time to provoke a hydrate meltdown it would be now. But “now” in a geological sense, over thousands of years in the future, not really “now” in a human sense. The methane hydrates in the ocean, in cahoots with permafrost peats (which never get enough respect), could be a significant multiplier of the long tail of the CO2, but will probably not be a huge player in climate change in the coming century.