Set theory is a branch of mathematical logic that studies sets,

which informally are collections of objects. Although any type of

object can be collected into a set, set theory is applied most often to

objects that are relevant to mathematics. The language of set theory can

be used to define nearly all mathematical objects.

The modern study of set theory was initiated by Georg Cantor and Richard Dedekind in the 1870s. After the discovery of paradoxes in naive set theory, such as Russell's paradox, numerous axiom systems were proposed in the early twentieth century, of which the Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms, with or without the axiom of choice, are the best-known.

Set theory is commonly employed as a foundational system for mathematics, particularly in the form of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice. Beyond its foundational role, set theory is a branch of mathematics

in its own right, with an active research community. Contemporary

research into set theory includes a diverse collection of topics,

ranging from the structure of the real number line to the study of the consistency of large cardinals.

History

Mathematical topics typically emerge and evolve through interactions

among many researchers. Set theory, however, was founded by a single

paper in 1874 by Georg Cantor: "On a Property of the Collection of All Real Algebraic Numbers".

Since the 5th century BC, beginning with Greek mathematician Zeno of Elea in the West and early Indian mathematicians in the East, mathematicians had struggled with the concept of infinity. Especially notable is the work of Bernard Bolzano in the first half of the 19th century. Modern understanding of infinity began in 1870–1874 and was motivated by Cantor's work in real analysis. An 1872 meeting between Cantor and Richard Dedekind influenced Cantor's thinking and culminated in Cantor's 1874 paper.

Cantor's work initially polarized the mathematicians of his day. While Karl Weierstrass and Dedekind supported Cantor, Leopold Kronecker, now seen as a founder of mathematical constructivism, did not. Cantorian set theory eventually became widespread, due to the utility of Cantorian concepts, such as one-to-one correspondence among sets, his proof that there are more real numbers than integers, and the "infinity of infinities" ("Cantor's paradise") resulting from the power set operation. This utility of set theory led to the article "Mengenlehre" contributed in 1898 by Arthur Schoenflies to Klein's encyclopedia.

The next wave of excitement in set theory came around 1900, when

it was discovered that some interpretations of Cantorian set theory gave

rise to several contradictions, called antinomies or paradoxes. Bertrand Russell and Ernst Zermelo independently found the simplest and best known paradox, now called Russell's paradox:

consider "the set of all sets that are not members of themselves",

which leads to a contradiction since it must be a member of itself and

not a member of itself. In 1899 Cantor had himself posed the question

"What is the cardinal number

of the set of all sets?", and obtained a related paradox. Russell used

his paradox as a theme in his 1903 review of continental mathematics in

his The Principles of Mathematics.

In 1906 English readers gained the book Theory of Sets of Points by husband and wife William Henry Young and Grace Chisholm Young, published by Cambridge University Press.

The momentum of set theory was such that debate on the paradoxes did not lead to its abandonment. The work of Zermelo in 1908 and the work of Abraham Fraenkel and Thoralf Skolem in 1922 resulted in the set of axioms ZFC, which became the most commonly used set of axioms for set theory. The work of analysts such as Henri Lebesgue

demonstrated the great mathematical utility of set theory, which has

since become woven into the fabric of modern mathematics. Set theory is

commonly used as a foundational system, although in some areas—such as

algebraic geometry and algebraic topology—category theory is thought to be a preferred foundation.

Basic concepts and notation

Set theory begins with a fundamental binary relation between an object o and a set A. If o is a member (or element) of A, the notation o ∈ A

is used. A set is described by listing elements separated by commas, or

by a characterizing property of its elements, within braces { }. Since

sets are objects, the membership relation can relate sets as well.

A derived binary relation between two sets is the subset relation, also called set inclusion. If all the members of set A are also members of set B, then A is a subset of B, denoted A ⊆ B. For example, {1, 2} is a subset of {1, 2, 3} , and so is {2} but {1, 4}

is not. As insinuated from this definition, a set is a subset of

itself. For cases where this possibility is unsuitable or would make

sense to be rejected, the term proper subset is defined. A is called a proper subset of B if and only if A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B. Also 1, 2, and 3 are members (elements) of the set {1, 2, 3} but are not subsets of it; and in turn, the subsets, such as {1}, are not members of the set {1, 2, 3}.

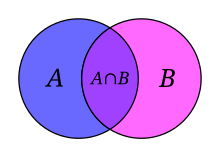

Just as arithmetic features binary operations on numbers, set theory features binary operations on sets. The:

- Union of the sets A and B, denoted A ∪ B, is the set of all objects that are a member of A, or B, or both. The union of {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} is the set {1, 2, 3, 4} .

- Intersection of the sets A and B, denoted A ∩ B, is the set of all objects that are members of both A and B. The intersection of {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} is the set {2, 3} .

- Set difference of U and A, denoted U \ A, is the set of all members of U that are not members of A. The set difference {1, 2, 3} \ {2, 3, 4} is {1} , while, conversely, the set difference {2, 3, 4} \ {1, 2, 3} is {4} . When A is a subset of U, the set difference U \ A is also called the complement of A in U. In this case, if the choice of U is clear from the context, the notation Ac is sometimes used instead of U \ A, particularly if U is a universal set as in the study of Venn diagrams.

- Symmetric difference of sets A and B, denoted A △ B or A ⊖ B, is the set of all objects that are a member of exactly one of A and B (elements which are in one of the sets, but not in both). For instance, for the sets {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} , the symmetric difference set is {1, 4} . It is the set difference of the union and the intersection, (A ∪ B) \ (A ∩ B) or (A \ B) ∪ (B \ A).

- Cartesian product of A and B, denoted A × B, is the set whose members are all possible ordered pairs (a, b) where a is a member of A and b is a member of B. The cartesian product of {1, 2} and {red, white} is {(1, red), (1, white), (2, red), (2, white)}.

- Power set of a set A is the set whose members are all of the possible subsets of A. For example, the power set of {1, 2} is { {}, {1}, {2}, {1, 2} } .

Some basic sets of central importance are the empty set (the unique set containing no elements; occasionally called the null set though this name is ambiguous), the set of natural numbers, and the set of real numbers.

Some ontology

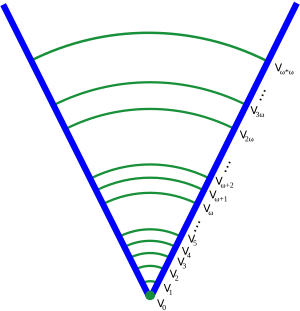

An initial segment of the von Neumann hierarchy.

A set is pure if all of its members are sets, all members of its members are sets, and so on. For example, the set {{}} containing only the empty set is a nonempty pure set. In modern set theory, it is common to restrict attention to the von Neumann universe

of pure sets, and many systems of axiomatic set theory are designed to

axiomatize the pure sets only. There are many technical advantages to

this restriction, and little generality is lost, because essentially all

mathematical concepts can be modeled by pure sets. Sets in the von

Neumann universe are organized into a cumulative hierarchy, based on how deeply their members, members of members, etc. are nested. Each set in this hierarchy is assigned (by transfinite recursion) an ordinal number , known as its rank. The rank of a pure set is defined to be the least upper bound of all successors of ranks of members of . For example, the empty set is assigned rank 0, while the set {{}} containing only the empty set is assigned rank 1. For each ordinal , the set is defined to consist of all pure sets with rank less than . The entire von Neumann universe is denoted .

Axiomatic set theory

Elementary set theory can be studied informally and intuitively, and so can be taught in primary schools using Venn diagrams.

The intuitive approach tacitly assumes that a set may be formed from

the class of all objects satisfying any particular defining condition.

This assumption gives rise to paradoxes, the simplest and best known of

which are Russell's paradox and the Burali-Forti paradox. Axiomatic set theory was originally devised to rid set theory of such paradoxes.

The most widely studied systems of axiomatic set theory imply that all sets form a cumulative hierarchy. Such systems come in two flavors, those whose ontology consists of:

- Sets alone. This includes the most common axiomatic set theory, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the Axiom of Choice (ZFC). Fragments of ZFC include:

- Zermelo set theory, which replaces the axiom schema of replacement with that of separation;

- General set theory, a small fragment of Zermelo set theory sufficient for the Peano axioms and finite sets;

- Kripke–Platek set theory, which omits the axioms of infinity, powerset, and choice, and weakens the axiom schemata of separation and replacement.

- Sets and proper classes. These include Von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel set theory, which has the same strength as ZFC for theorems about sets alone, and Morse–Kelley set theory and Tarski–Grothendieck set theory, both of which are stronger than ZFC.

The above systems can be modified to allow urelements, objects that can be members of sets but that are not themselves sets and do not have any members.

The New Foundations systems of NFU (allowing urelements) and NF

(lacking them) are not based on a cumulative hierarchy. NF and NFU

include a "set of everything, " relative to which every set has a

complement. In these systems urelements matter, because NF, but not NFU,

produces sets for which the axiom of choice does not hold.

Systems of constructive set theory, such as CST, CZF, and IZF, embed their set axioms in intuitionistic instead of classical logic. Yet other systems accept classical logic but feature a nonstandard membership relation. These include rough set theory and fuzzy set theory, in which the value of an atomic formula embodying the membership relation is not simply True or False. The Boolean-valued models of ZFC are a related subject.

Applications

Many

mathematical concepts can be defined precisely using only set theoretic

concepts. For example, mathematical structures as diverse as graphs, manifolds, rings, and vector spaces can all be defined as sets satisfying various (axiomatic) properties. Equivalence and order relations are ubiquitous in mathematics, and the theory of mathematical relations can be described in set theory.

Set theory is also a promising foundational system for much of mathematics. Since the publication of the first volume of Principia Mathematica,

it has been claimed that most or even all mathematical theorems can be

derived using an aptly designed set of axioms for set theory, augmented

with many definitions, using first or second-order logic. For example, properties of the natural and real numbers can be derived within set theory, as each number system can be identified with a set of equivalence classes under a suitable equivalence relation whose field is some infinite set.

Set theory as a foundation for mathematical analysis, topology, abstract algebra, and discrete mathematics

is likewise uncontroversial; mathematicians accept that (in principle)

theorems in these areas can be derived from the relevant definitions and

the axioms of set theory. Few full derivations of complex mathematical

theorems from set theory have been formally verified, however, because

such formal derivations are often much longer than the natural language

proofs mathematicians commonly present. One verification project, Metamath, includes human-written, computer-verified derivations of more than 12,000 theorems starting from ZFC set theory, first-order logic and propositional logic.

Areas of study

Set theory is a major area of research in mathematics, with many interrelated subfields.

Combinatorial set theory

Combinatorial set theory concerns extensions of finite combinatorics to infinite sets. This includes the study of cardinal arithmetic and the study of extensions of Ramsey's theorem such as the Erdős–Rado theorem.

Descriptive set theory

Descriptive set theory is the study of subsets of the real line and, more generally, subsets of Polish spaces. It begins with the study of pointclasses in the Borel hierarchy and extends to the study of more complex hierarchies such as the projective hierarchy and the Wadge hierarchy. Many properties of Borel sets

can be established in ZFC, but proving these properties hold for more

complicated sets requires additional axioms related to determinacy and

large cardinals.

The field of effective descriptive set theory is between set theory and recursion theory. It includes the study of lightface pointclasses, and is closely related to hyperarithmetical theory.

In many cases, results of classical descriptive set theory have

effective versions; in some cases, new results are obtained by proving

the effective version first and then extending ("relativizing") it to

make it more broadly applicable.

A recent area of research concerns Borel equivalence relations and more complicated definable equivalence relations. This has important applications to the study of invariants in many fields of mathematics.

Fuzzy set theory

In set theory as Cantor defined and Zermelo and Fraenkel axiomatized, an object is either a member of a set or not. In fuzzy set theory this condition was relaxed by Lotfi A. Zadeh so an object has a degree of membership

in a set, a number between 0 and 1. For example, the degree of

membership of a person in the set of "tall people" is more flexible than

a simple yes or no answer and can be a real number such as 0.75.

Inner model theory

An inner model of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZF) is a transitive class that includes all the ordinals and satisfies all the axioms of ZF. The canonical example is the constructible universe L

developed by Gödel.

One reason that the study of inner models is of interest is that it can

be used to prove consistency results. For example, it can be shown that

regardless of whether a model V of ZF satisfies the continuum hypothesis or the axiom of choice, the inner model L

constructed inside the original model will satisfy both the generalized

continuum hypothesis and the axiom of choice. Thus the assumption that

ZF is consistent (has at least one model) implies that ZF together with

these two principles is consistent.

The study of inner models is common in the study of determinacy and large cardinals,

especially when considering axioms such as the axiom of determinacy

that contradict the axiom of choice. Even if a fixed model of set theory

satisfies the axiom of choice, it is possible for an inner model to

fail to satisfy the axiom of choice. For example, the existence of

sufficiently large cardinals implies that there is an inner model

satisfying the axiom of determinacy (and thus not satisfying the axiom

of choice).

Large cardinals

A large cardinal is a cardinal number with an extra property. Many such properties are studied, including inaccessible cardinals, measurable cardinals,

and many more. These properties typically imply the cardinal number

must be very large, with the existence of a cardinal with the specified

property unprovable in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory.

Determinacy

Determinacy refers to the fact that, under appropriate

assumptions, certain two-player games of perfect information are

determined from the start in the sense that one player must have a

winning strategy. The existence of these strategies has important

consequences in descriptive set theory, as the assumption that a broader

class of games is determined often implies that a broader class of sets

will have a topological property. The axiom of determinacy

(AD) is an important object of study; although incompatible with the

axiom of choice, AD implies that all subsets of the real line are well

behaved (in particular, measurable and with the perfect set property).

AD can be used to prove that the Wadge degrees have an elegant structure.

Forcing

Paul Cohen invented the method of forcing while searching for a model of ZFC in which the continuum hypothesis fails, or a model of ZF in which the axiom of choice

fails. Forcing adjoins to some given model of set theory additional

sets in order to create a larger model with properties determined (i.e.

"forced") by the construction and the original model. For example,

Cohen's construction adjoins additional subsets of the natural numbers without changing any of the cardinal numbers of the original model. Forcing is also one of two methods for proving relative consistency by finitistic methods, the other method being Boolean-valued models.

Cardinal invariants

A cardinal invariant is a property of the real line measured

by a cardinal number. For example, a well-studied invariant is the

smallest cardinality of a collection of meagre sets

of reals whose union is the entire real line. These are invariants in

the sense that any two isomorphic models of set theory must give the

same cardinal for each invariant. Many cardinal invariants have been

studied, and the relationships between them are often complex and

related to axioms of set theory.

Set-theoretic topology

Set-theoretic topology studies questions of general topology

that are set-theoretic in nature or that require advanced methods of

set theory for their solution. Many of these theorems are independent of

ZFC, requiring stronger axioms for their proof. A famous problem is the

normal Moore space question,

a question in general topology that was the subject of intense

research. The answer to the normal Moore space question was eventually

proved to be independent of ZFC.

Objections to set theory as a foundation for mathematics

From set theory's inception, some mathematicians have objected to it as a foundation for mathematics. The most common objection to set theory, one Kronecker voiced in set theory's earliest years, starts from the constructivist view that mathematics is loosely related to computation. If this view is granted, then the treatment of infinite sets, both in naive

and in axiomatic set theory, introduces into mathematics methods and

objects that are not computable even in principle. The feasibility of

constructivism as a substitute foundation for mathematics was greatly

increased by Errett Bishop's influential book Foundations of Constructive Analysis.

A different objection put forth by Henri Poincaré is that defining sets using the axiom schemas of specification and replacement, as well as the axiom of power set, introduces impredicativity, a type of circularity,

into the definitions of mathematical objects. The scope of

predicatively founded mathematics, while less than that of the commonly

accepted Zermelo-Fraenkel theory, is much greater than that of

constructive mathematics, to the point that Solomon Feferman has said that "all of scientifically applicable analysis can be developed [using predicative methods]".

Ludwig Wittgenstein condemned set theory philosophically for its connotations of Mathematical platonism.

He wrote that "set theory is wrong", since it builds on the "nonsense"

of fictitious symbolism, has "pernicious idioms", and that it is

nonsensical to talk about "all numbers". Wittgenstein identified mathematics with algorithmic human deduction; the need for a secure foundation for mathematics seemed, to him, nonsensical. Moreover, since human effort is necessarily finite, Wittgenstein's philosophy required an ontological commitment to radical constructivism and finitism.

Meta-mathematical statements — which, for Wittgenstein, included any

statement quantifying over infinite domains, and thus almost all modern

set theory — are not mathematics. Few modern philosophers have adopted Wittgenstein's views after a spectacular blunder in Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics: Wittgenstein attempted to refute Gödel's incompleteness theorems after having only read the abstract. As reviewers Kreisel, Bernays, Dummett, and Goodstein all pointed out, many of his critiques did not apply to the paper in full. Only recently have philosophers such as Crispin Wright begun to rehabilitate Wittgenstein's arguments.

Category theorists have proposed topos theory as an alternative to traditional axiomatic set theory. Topos theory can interpret various alternatives to that theory, such as constructivism, finite set theory, and computable set theory.

Topoi also give a natural setting for forcing and discussions of the

independence of choice from ZF, as well as providing the framework for pointless topology and Stone spaces.

An active area of research is the univalent foundations and related to it homotopy type theory. Within homotopy type theory, a set may be regarded as a homotopy 0-type, with universal properties of sets arising from the inductive and recursive properties of higher inductive types. Principles such as the axiom of choice and the law of the excluded middle

can be formulated in a manner corresponding to the classical

formulation in set theory or perhaps in a spectrum of distinct ways

unique to type theory. Some of these principles may be proven to be a

consequence of other principles. The variety of formulations of these

axiomatic principles allows for a detailed analysis of the formulations

required in order to derive various mathematical results.

Set theory in mathematical education

As

set theory gained popularity as a foundation for modern mathematics,

there has been support for the idea of introducing basic theory, or naive set theory, early in mathematics education.

In the US in the 1960s, the New Math

experiment aimed to teach basic set theory, among other abstract

concepts, to primary grade students, but was met with much criticism.

The math syllabus in European schools followed this trend, and currently

includes the subject at different levels in all grades.

Set theory is used to introduce students to logical operators (NOT, AND, OR) and semantic or rule description (technically intensional definition) of sets, (e.g. "months starting with the letter A"). This may be useful when learning computer programming, as sets and boolean logic are basic building blocks of many programming languages.

Sets are commonly referred to when teaching about different types of numbers (N, Z, R, ...) and when defining mathematical functions as a relationship between two sets.

![\exists A^{n+1}\forall x^{n}[x^{n}\in A^{n+1}\leftrightarrow \phi (x^{n})]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a595a956deeeede9e5fa14afd1d826adf574bdbe)