A hierarchy (from Greek: ἱεραρχία, hierarkhia, 'rule of a high priest', from hierarkhes, 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important concept in a wide variety of fields, such as architecture, philosophy, design, mathematics, computer science, organizational theory, systems theory, systematic biology, and the social sciences (especially political philosophy).

A hierarchy can link entities either directly or indirectly, and either vertically or diagonally. The only direct links in a hierarchy, insofar as they are hierarchical, are to one's immediate superior or to one of one's subordinates, although a system that is largely hierarchical can also incorporate alternative hierarchies. Hierarchical links can extend "vertically" upwards or downwards via multiple links in the same direction, following a path. All parts of the hierarchy that are not linked vertically to one another nevertheless can be "horizontally" linked through a path by traveling up the hierarchy to find a common direct or indirect superior, and then down again. This is akin to two co-workers or colleagues; each reports to a common superior, but they have the same relative amount of authority. Organizational forms exist that are both alternative and complementary to hierarchy. Heterarchy is one such form.

Nomenclature

Hierarchies have their own special vocabulary. These terms are easiest to understand when a hierarchy is diagrammed (see below).

In an organizational context, the following terms are often used related to hierarchies:

- Object: one entity (e.g., a person, department or concept or element of arrangement or member of a set)

- System: the entire set of objects that are being arranged hierarchically (e.g., an administration)

- Dimension: another word for "system" from on-line analytical processing (e.g. cubes)

- Member: an (element or object) at any (level or rank) in a (class-system, taxonomy or dimension)

- Terms about Positioning

- Rank: the relative value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level etc. of an object

- Level or Tier: a set of objects with the same rank OR importance

- Ordering: the arrangement of the (ranks or levels)

- Hierarchy: the arrangement of a particular set of members into (ranks or levels). Multiple hierarchies are possible per (dimension taxonomy or Classification-system), in which selected levels of the dimension are omitted to flatten the structure

- Terms about Placement

- Hierarch, the apex of the hierarchy, consisting of one single orphan (object or member) in the top level of a dimension. The root of an inverted-tree structure

- Member, a (member or node) in any level of a hierarchy in a dimension to which (superior and subordinate) members are attached

- Orphan, a member in any level of a dimension without a parent member. Often the apex of a disconnected branch. Orphans can be grafted back into the hierarchy by creating a relationship (interaction) with a parent in the immediately superior level

- Leaf, a member in any level of a dimension without subordinates in the hierarchy

- Neighbour: a member adjacent to another member in the same (level or rank). Always a peer.

- Superior: a higher level or an object ranked at a higher level (A parent or an ancestor)

- Subordinate: a lower level or an object ranked at a lower level (A child or a descendant)

- Collection: all of the objects at one level (i.e. Peers)

- Peer: an object with the same rank (and therefore at the same level)

- Interaction: the relationship between an object and its direct superior or subordinate (i.e. a superior/inferior pair)

- a direct interaction occurs when one object is on a level exactly one higher or one lower than the other (i.e., on a tree, the two objects have a line between them)

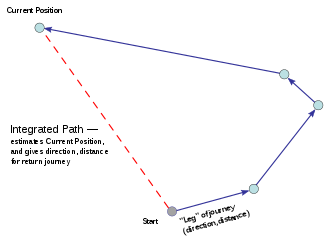

- Distance: the minimum number of connections between two objects, i.e., one less than the number of objects that need to be "crossed" to trace a path from one object to another

- Span: a qualitative description of the width of a level when diagrammed, i.e., the number of subordinates an object has

- Terms about Nature

- Attribute: a heritable characteristic of (members and their subordinates) in a level (e.g. hair-colour)

- Attribute-value: the specific value of a heritable characteristic (e.g. Auburn)

In a mathematical context (in graph theory), the general terminology used is different.

Most hierarchies use a more specific vocabulary pertaining to their subject, but the idea behind them is the same. For example, with data structures, objects are known as nodes, superiors are called parents and subordinates are called children. In a business setting, a superior is a supervisor/boss and a peer is a colleague.

Degree of branching

Degree of branching refers to the number of direct subordinates or children an object has (in graph theory, equivalent to the number of other vertices connected to via outgoing arcs, in a directed graph) a node has. Hierarchies can be categorized based on the "maximum degree", the highest degree present in the system as a whole. Categorization in this way yields two broad classes: linear and branching.

In a linear hierarchy, the maximum degree is 1. In other words, all of the objects can be visualized in a line-up, and each object (excluding the top and bottom ones) has exactly one direct subordinate and one direct superior. Note that this is referring to the objects and not the levels; every hierarchy has this property with respect to levels, but normally each level can have an infinite number of objects. An example of a linear hierarchy is the hierarchy of life.

In a branching hierarchy, one or more objects has a degree of 2 or more (and therefore the minimum degree is 2 or higher). For many people, the word "hierarchy" automatically evokes an image of a branching hierarchy. Branching hierarchies are present within numerous systems, including organizations and classification schemes. The broad category of branching hierarchies can be further subdivided based on the degree.

A flat hierarchy (also known for companies as flat organization) is a branching hierarchy in which the maximum degree approaches infinity, i.e., that has a wide span. Most often, systems intuitively regarded as hierarchical have at most a moderate span. Therefore, a flat hierarchy is often not viewed as a hierarchy at all. For example, diamonds and graphite are flat hierarchies of numerous carbon atoms that can be further decomposed into subatomic particles.

An overlapping hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which at least one object has two parent objects. For example, a graduate student can have two co-supervisors to whom the student reports directly and equally, and who have the same level of authority within the university hierarchy (i.e., they have the same position or tenure status).

Etymology

Possibly the first use of the English word hierarchy cited by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1881, when it was used in reference to the three orders of three angels as depicted by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th–6th centuries). Pseudo-Dionysius used the related Greek word (ἱεραρχία, hierarchia) both in reference to the celestial hierarchy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The Greek term hierarchia means 'rule of a high priest', from hierarches (ἱεράρχης, 'president of sacred rites, high-priest') and that from hiereus (ἱερεύς, 'priest') and arche (ἀρχή, 'first place or power, rule'). Dionysius is credited with first use of it as an abstract noun.

Since hierarchical churches, such as the Roman Catholic (see Catholic Church hierarchy) and Eastern Orthodox churches, had tables of organization that were "hierarchical" in the modern sense of the word (traditionally with God as the pinnacle or head of the hierarchy), the term came to refer to similar organizational methods in secular settings.

Representing hierarchies

A hierarchy is typically depicted as a pyramid, where the height of a level represents that level's status and width of a level represents the quantity of items at that level relative to the whole. For example, the few Directors of a company could be at the apex, and the base could be thousands of people who have no subordinates.

These pyramids are often diagrammed with a triangle diagram which serves to emphasize the size differences between the levels (but note that not all triangle/pyramid diagrams are hierarchical; for example, the 1992 USDA food guide pyramid). An example of a triangle diagram appears to the right.

Another common representation of a hierarchical scheme is as a tree diagram. Phylogenetic trees, charts showing the structure of § organizations, and playoff brackets in sports are often illustrated this way.

More recently, as computers have allowed the storage and navigation of ever larger data sets, various methods have been developed to represent hierarchies in a manner that makes more efficient use of the available space on a computer's screen. Examples include fractal maps, TreeMaps and Radial Trees.

Visual hierarchy

In the design field, mainly graphic design, successful layouts and formatting of the content on documents are heavily dependent on the rules of visual hierarchy. Visual hierarchy is also important for proper organization of files on computers.

An example of visually representing hierarchy is through nested clusters. Nested clusters represent hierarchical relationships using layers of information. The child element is within the parent element, such as in a Venn diagram. This structure is most effective in representing simple hierarchical relationships. For example, when directing someone to open a file on a computer desktop, one may first direct them towards the main folder, then the subfolders within the main folder. They will keep opening files within the folders until the designated file is located.

For more complicated hierarchies, the stair structure represents hierarchical relationships through the use of visual stacking. Visually imagine the top of a downward staircase beginning at the left and descending on the right. Child elements are towards the bottom of the stairs and parent elements are at the top. This structure represents hierarchical relationships through the use of visual stacking.

Informal representation

In plain English, a hierarchy can be thought of as a set in which:

- No element is superior to itself, and

- One element, the hierarch, is superior to all of the other elements in the set.

The first requirement is also interpreted to mean that a hierarchy can have no circular relationships; the association between two objects is always transitive. The second requirement asserts that a hierarchy must have a leader or root that is common to all of the objects.

Mathematical representation

Mathematically, in its most general form, a hierarchy is a partially ordered set or poset. The system in this case is the entire poset, which is constituted of elements. Within this system, each element shares a particular unambiguous property. Objects with the same property value are grouped together, and each of those resulting levels is referred to as a class.

"Hierarchy" is particularly used to refer to a poset in which the classes are organized in terms of increasing complexity. Operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are often performed in a certain sequence or order. Usually, addition and subtraction are performed after multiplication and division has already been applied to a problem. The use of parentheses is also a representation of hierarchy, for they show which operation is to be done prior to the following ones. For example: (2 + 5) × (7 - 4). In this problem, typically one would multiply 5 by 7 first, based on the rules of mathematical hierarchy. But when the parentheses are placed, one will know to do the operations within the parentheses first before continuing on with the problem. These rules are largely dominant in algebraic problems, ones that include several steps to solve. The use of hierarchy in mathematics is beneficial to quickly and efficiently solve a problem without having to go through the process of slowly dissecting the problem. Most of these rules are now known as the proper way into solving certain equations.

Subtypes

Nested hierarchy

A nested hierarchy or inclusion hierarchy is a hierarchical ordering of nested sets. The concept of nesting is exemplified in Russian matryoshka dolls. Each doll is encompassed by another doll, all the way to the outer doll. The outer doll holds all of the inner dolls, the next outer doll holds all the remaining inner dolls, and so on. Matryoshkas represent a nested hierarchy where each level contains only one object, i.e., there is only one of each size of doll; a generalized nested hierarchy allows for multiple objects within levels but with each object having only one parent at each level. The general concept is both demonstrated and mathematically formulated in the following example:

A square can always also be referred to as a quadrilateral, polygon or shape. In this way, it is a hierarchy. However, consider the set of polygons using this classification. A square can only be a quadrilateral; it can never be a triangle, hexagon, etc.

Nested hierarchies are the organizational schemes behind taxonomies and systematic classifications. For example, using the original Linnaean taxonomy (the version he laid out in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae), a human can be formulated as:

Taxonomies may change frequently (as seen in biological taxonomy), but the underlying concept of nested hierarchies is always the same.

In many programming taxonomies and syntax models (as well as fractals in mathematics), nested hierarchies, including Russian dolls, are also used to illustrate the properties of self-similarity and recursion. Recursion itself is included as a subset of hierarchical programming, and recursive thinking can be synonymous with a form of hierarchical thinking and logic.

Containment hierarchy

A containment hierarchy is a direct extrapolation of the nested hierarchy concept. All of the ordered sets are still nested, but every set must be "strict"—no two sets can be identical. The shapes example above can be modified to demonstrate this:

The notation means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

A general example of a containment hierarchy is demonstrated in class inheritance in object-oriented programming.

Two types of containment hierarchies are the subsumptive containment hierarchy and the compositional containment hierarchy. A subsumptive hierarchy "subsumes" its children, and a compositional hierarchy is "composed" of its children. A hierarchy can also be both subsumptive and compositional.

Subsumptive containment hierarchy

A subsumptive containment hierarchy is a classification of object classes from the general to the specific. Other names for this type of hierarchy are "taxonomic hierarchy" and "IS-A hierarchy". The last term describes the relationship between each level—a lower-level object "is a" member of the higher class. The taxonomical structure outlined above is a subsumptive containment hierarchy. Using again the example of Linnaean taxonomy, it can be seen that an object that is part of the level Mammalia "is a" member of the level Animalia; more specifically, a human "is a" primate, a primate "is a" mammal, and so on. A subsumptive hierarchy can also be defined abstractly as a hierarchy of "concepts". For example, with the Linnaean hierarchy outlined above, an entity name like Animalia is a way to group all the species that fit the conceptualization of an animal.

Compositional containment hierarchy

A compositional containment hierarchy is an ordering of the parts that make up a system—the system is "composed" of these parts. Most engineered structures, whether natural or artificial, can be broken down in this manner.

The compositional hierarchy that every person encounters at every moment is the hierarchy of life. Every person can be reduced to organ systems, which are composed of organs, which are composed of tissues, which are composed of cells, which are composed of molecules, which are composed of atoms. In fact, the last two levels apply to all matter, at least at the macroscopic scale. Moreover, each of these levels inherit all the properties of their children.

In this particular example, there are also emergent properties—functions that are not seen at the lower level (e.g., cognition is not a property of neurons but is of the brain)—and a scalar quality (molecules are bigger than atoms, cells are bigger than molecules, etc.). Both of these concepts commonly exist in compositional hierarchies, but they are not a required general property. These level hierarchies are characterized by bi-directional causation. Upward causation involves lower-level entities causing some property of a higher level entity; children entities may interact to yield parent entities, and parents are composed at least partly by their children. Downward causation refers to the effect that the incorporation of entity x into a higher-level entity can have on x's properties and interactions. Furthermore, the entities found at each level are autonomous.

Contexts and applications

Kulish (2002) suggests that almost every system of organization which humans apply to the world is arranged hierarchically. Some conventional definitions of the terms "nation" and "government" suggest that every nation has a government and that every government is hierarchical. Sociologists can analyse socioeconomic systems in terms of stratification into a social hierarchy (the social stratification of societies), and all systematic classification schemes (taxonomies) are hierarchical. Most organized religions, regardless of their internal governance structures, operate as a hierarchy under deities and priesthoods. Many Christian denominations have an autocephalous ecclesiastical hierarchy of leadership. Families can be viewed as hierarchical structures in terms of cousinship (e.g., first cousin once removed, second cousin, etc.), ancestry (as depicted in a family tree) and inheritance (succession and heirship). All the requisites of a well-rounded life and lifestyle can be organized using Maslow's hierarchy of human needs - according to Maslow's hierarchy of human needs. Learning steps often follow a hierarchical scheme—to master differential equations one must first learn calculus; to learn calculus one must first learn elementary algebra; and so on. Nature offers hierarchical structures, as numerous schemes such as Linnaean taxonomy, the organization of life, and biomass pyramids attempt to document. Hierarchies are so infused into daily life that they are viewed as trivial.

While the above examples are often clearly depicted in a hierarchical form and are classic examples, hierarchies exist in numerous systems where this branching structure is not immediately apparent. For example, most postal-code systems are hierarchical. Using the Canadian postal code system as an example, the top level's binding concept, the "postal district", consists of 18 objects (letters). The next level down is the "zone", where the objects are the digits 0–9. This is an example of an overlapping hierarchy, because each of these 10 objects has 18 parents. The hierarchy continues downward to generate, in theory, 7,200,000 unique codes of the format A0A 0A0 (the second and third letter positions allow 20 objects each). Most library classification systems are also hierarchical. The Dewey Decimal System is infinitely hierarchical because there is no finite bound on the number of digits can be used after the decimal point.

Organizations

Organizations can be structured as a dominance hierarchy. In an organizational hierarchy, there is a single person or group with the most power or authority, and each subsequent level represents a lesser authority. Most organizations are structured in this manner, including governments, companies, armed forces, militia and organized religions. The units or persons within an organization may be depicted hierarchically in an organizational chart.

In a reverse hierarchy, the conceptual pyramid of authority is turned upside-down, so that the apex is at the bottom and the base is at the top. This mode represents the idea that members of the higher rankings are responsible for the members of the lower rankings.

Biology

Empirically, when we observe in nature a large proportion of the (complex) biological systems, they exhibit hierarchic structure. On theoretical grounds we could expect complex systems to be hierarchies in a world in which complexity had to evolve from simplicity. System hierarchies analysis performed in the 1950s, laid the empirical foundations for a field that would become, from the 1980s, hierarchical ecology.

The theoretical foundations are summarized by thermodynamics. When biological systems are modeled as physical systems, in the most general abstraction, they are thermodynamic open systems that exhibit self-organised behavior, and the set/subset relations between dissipative structures can be characterized in a hierarchy.

Other hierarchical representations related to biology include ecological pyramids which illustrate energy flow or trophic levels in ecosystems, and taxonomic hierarchies, including the Linnean classification scheme and phylogenetic trees that reflect inferred patterns of evolutionary relationship among living and extinct species.

Computer-graphic imaging

CGI and computer-animation programs mostly use hierarchies for models. On a 3D model of a human for example, the chest is a parent of the upper left arm, which is a parent of the lower left arm, which is a parent of the hand. This pattern is used in modeling and animation for almost everything built as a 3D digital model.

Linguistics

Many grammatical theories, such as phrase-structure grammar, involve hierarchy.

Direct–inverse languages such as Cree and Mapudungun distinguish subject and object on verbs not by different subject and object markers, but via a hierarchy of persons.

In this system, the three (or four with Algonquian languages) persons occur in a hierarchy of salience. To distinguish which is subject and which object, inverse markers are used if the object outranks the subject.

On the other hand, languages include a variety of phenomena that are not hierarchical. For example, the relationship between a pronoun and a prior noun-phrase to which it refers commonly crosses grammatical boundaries in non-hierarchical ways.

Music

The structure of a musical composition is often understood hierarchically (for example by Heinrich Schenker (1768–1835, see Schenkerian analysis), and in the (1985) Generative Theory of Tonal Music, by composer Fred Lerdahl and linguist Ray Jackendoff). The sum of all notes in a piece is understood to be an all-inclusive surface, which can be reduced to successively more sparse and more fundamental types of motion. The levels of structure that operate in Schenker's theory are the foreground, which is seen in all the details of the musical score; the middle ground, which is roughly a summary of an essential contrapuntal progression and voice-leading; and the background or Ursatz, which is one of only a few basic "long-range counterpoint" structures that are shared in the gamut of tonal music literature.

The pitches and form of tonal music are organized hierarchically, all pitches deriving their importance from their relationship to a tonic key, and secondary themes in other keys are brought back to the tonic in a recapitulation of the primary theme.