Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is the process of extracting bioenergy from biomass and capturing and storing the carbon, thereby removing it from the atmosphere. The carbon in the biomass comes from the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) which is extracted from the atmosphere by the biomass when it grows. Energy is extracted in useful forms (electricity, heat, biofuels, etc.) as the biomass is utilized through combustion, fermentation, pyrolysis or other conversion methods. Some of the carbon in the biomass is converted to CO2 or biochar which can then be stored by geologic sequestration or land application, respectively, enabling carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and making BECCS a negative emissions technology (NET).

The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), suggests a potential range of negative emissions from BECCS of 0 to 22 gigatonnes per year. As of 2019, five facilities around the world were actively using BECCS technologies and were capturing approximately 1.5 million tonnes per year of CO2. Wide deployment of BECCS is constrained by cost and availability of biomass.

Negative emission

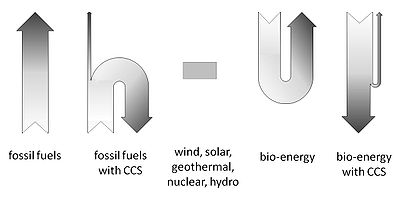

The main appeal of BECCS is in its ability to result in negative emissions of CO2. The capture of carbon dioxide from bioenergy sources effectively removes CO2 from the atmosphere.

Bioenergy is derived from biomass which is a renewable energy source and serves as a carbon sink during its growth. During industrial processes, the biomass combusted or processed re-releases the CO2 into the atmosphere. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology serves to intercept the release of CO2 into the atmosphere and redirect it into geological storage locations or concrete. The process thus results in a net zero emission of CO2, though this may be positively or negatively altered depending on the carbon emissions associated with biomass growth, transport and processing, see below under environmental considerations. CO2 with a biomass origin is not only released from biomass fuelled power plants, but also during the production of pulp used to make paper and in the production of biofuels such as biogas and bioethanol. The BECCS technology can also be employed on industrial processes such as these and making cement.

BECCS technologies trap carbon dioxide in geologic formations in a semi-permanent way, whereas a tree stores its carbon only during its lifetime. The IPCC special report on CCS technology projected that more than 99% of carbon dioxide stored through geologic sequestration is likely to stay in place for more than 1000 years. While other types of carbon sinks such as the ocean, trees and soil may involve the risk of adverse feedback loops at increased temperatures, BECCS technology is likely to provide a better permanence by storing CO2 in geological formations.

Industrial processes have released too much CO2 to be absorbed by conventional sinks such as trees and soil to reach low emission targets. In addition to the presently accumulated emissions, there will be significant additional emissions during this century, even in the most ambitious low-emission scenarios. BECCS has therefore been suggested as a technology to reverse the emission trend and create a global system of net negative emissions. This implies that the emissions would not only be zero, but negative, so that not only the emissions, but the absolute amount of CO2 in the atmosphere would be reduced.

Application

| Source | CO2 Source | Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol production | Fermentation of biomass such as sugarcane, wheat or corn releases CO2 as a by-product | Industry |

| Pulp and paper mills

Cement production |

|

Industry |

| Biogas production | In the biogas upgrading process, CO2 is separated from the methane to produce a higher quality gas | Industry |

| Electrical power plants | Combustion of biomass or biofuel in steam or gas powered generators releases CO2 as a by-product | Energy |

| Heat power plants | Combustion of biofuel for heat generation releases CO2 as a by-product. Usually used for district heating | Energy |

Cost

The IPCC states that estimations for BECCS cost range from $60-$250 per ton of CO2.

Research by Rau et al. (2018) estimates that electrogeochemical methods of combining saline water electrolysis with mineral weathering powered by non-fossil fuel-derived electricity could, on average, increase both energy generation and CO2 removal by more than 50 times relative to BECCS, at equivalent or even lower cost, but further research is needed to develop such methods.

Technology

The main technology for CO2 capture from biotic sources generally employs the same technology as carbon dioxide capture from conventional fossil fuel sources. Broadly, three different types of technologies exist: post-combustion, pre-combustion, and oxy-fuel combustion.

Oxy-combustion

Oxy‐fuel combustion has been a common process in the glass, cement and steel industries. It is also a promising technological approach for CCS. In oxy‐fuel combustion, the main difference from conventional air firing is that the fuel is burned in a mixture of O2 and recycled flue gas. The O2 is produced by an air separation unit (ASU), which removes the atmospheric N2 from the oxidizer stream. By removing the N2 upstream of the process, a flue gas with a high concentration of CO2 and water vapor is produced, which eliminates the need for a post‐combustion capture plant. The water vapor can be removed by condensation, leaving a product stream of relatively high‐purity CO2 which, after subsequent purification and dehydration, can be pumped to a geological storage site.

Key challenges of BECCS implementation using oxy-combustion are associated with the combustion process. For the high volatile content biomass, the mill temperature has to be kept at a low temperature to reduce the risk of fire and explosion. In addition, the flame temperature is lower. Therefore, the concentration of oxygen needs to be increased up to 27-30%.

Pre-combustion

"Pre-combustion carbon capture" describes processes that capture CO2 before generating energy. This is often accomplished in five operating stages: oxygen generation, syngas generation, CO2 separation, CO2 compression, and power generation. The fuel first goes through a gasification process by reacting with oxygen to form a stream of CO and H2, which is syngas. The products will then go through a water-gas shift reactor to form CO2 and H2. The CO2 that is produced will then be captured, and the H2, which is a clean source, will be used for combustion to generate energy. The process of gasification combined with syngas production is called Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC). An Air Separation Unit (ASU) can serve as the oxygen source, but some research has found that with the same flue gas, oxygen gasification is only slightly better than air gasification. Both have a thermal efficiency of roughly 70% using coal as the fuel source. Thus, the use of an ASU is not really necessary in pre-combustion.

Biomass is considered "sulfur-free" as a fuel for the pre-combustion capture. However, there are other trace elements in biomass combustion such as K and Na that could accumulate in the system and finally cause the degradation of the mechanical parts. Thus, further developments of the separation techniques for those trace elements are needed. And also, after the gasification process, CO2 takes up to 13% - 15.3% by mass in the syngas stream for biomass sources, while it is only 1.7% - 4.4% for coal. This limit the conversion of CO to CO2 in the water gas shift, and the production rate for H2 will decrease accordingly. However, the thermal efficiency of the pre-combustion capture using biomass resembles that of coal which is around 62% - 100%. Some research found that using a dry system instead of a biomass/water slurry fuel feed was more thermally efficient and practical for biomass.

Post-combustion

In addition to pre-combustion and oxy-fuel combustion technologies, post-combustion is a promising technology which can be used to extract CO2 emission from biomass fuel resources. During the process, CO2 is separated from the other gases in the flue gas stream after the biomass fuel is burnt and undergo separation process. Because it has the ability to be retrofitted to some existing power plants such as steam boilers or other newly built power stations, post-combustion technology is considered as a better option than pre-combustion technology. According to the fact sheets U.S. CONSUMPTION OF BIO-ENERGY WITH CARBON CAPTURE AND STORAGE released in March 2018, the efficiency of post-combustion technology is expected to be 95% while pre-combustion and oxy-combustion capture CO2 at an efficient rate of 85% and 87.5% respectively.

Development for current post-combustion technologies has not been entirely done due to several problems. One of the major concerns using this technology to capture carbon dioxide is the parasitic energy consumption. If the capacity of the unit is designed to be small, the heat loss to the surrounding is great enough to cause too many negative consequences. Another challenge of post-combustion carbon capture is how to deal with the mixture's components in the flue gases from initial biomass materials after combustion. The mixture consists of a high amount of alkali metals, halogens, acidic elements, and transition metals which might have negative impacts on the efficiency of the process. Thus, the choice of specific solvents and how to manage the solvent process should be carefully designed and operated.

Biomass feedstocks

Biomass sources used in BECCS include agricultural residues & waste, forestry residue & waste, industrial & municipal wastes, and energy crops specifically grown for use as fuel. Current BECCS projects capture CO2 from ethanol bio-refinery plants and municipal solid waste (MSW) recycling center.

A variety of challenges must be faced to ensure that biomass-based carbon capture is feasible and carbon neutral. Biomass stocks require availability of water and fertilizer inputs, which themselves exist at a nexus of environmental challenges in terms of resource disruption, conflict, and fertilizer runoff. A second major challenge is logistical: bulky biomass products require transportation to geographical features that enable sequestration.

Current projects

To date, there have been 23 BECCS projects around the world, with the majority in North America and Europe. Today, there are only 6 projects in operation, capturing CO2 from ethanol bio-refinery plants and MSW recycling centers.

At ethanol plants

Illinois Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage (IL-CCS) is one of the milestones, being the first industrial-scaled BECCS project, in the early 21st century. Located in Decatur, Illinois, USA, IL-CCS captures CO2 from Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) ethanol plant. The captured CO2 is then injected under the deep saline formation at Mount Simon Sandstone. IL-CCS consists of 2 phases. The first being a pilot project which was implemented from 11/2011 to 11/2014. Phase 1 has a capital cost of around 84 million US dollars. Over the 3-year period, the technology successfully captured and sequestered 1million tonne of CO2 from the ADM plant to the aquifer. No leaking of CO2 from the injection zone was found during this period. The project is still being monitored for future reference. The success of phase 1 motivated the deployment of phase 2, bringing IL-CCS (and BECCS) to industrial scale. Phase 2 has been in operation since 11/2017 and also use the same injection zone at Mount Simon Sandstone as phase 1. The capital cost for second phase is about 208 million US dollars including 141 million US dollar fund from the Department of Energy. Phase 2 has capturing capacity about 3 time larger than the pilot project (phase 1). Annually, IL-CCS can capture more than 1 million tonne of CO2. With the largest of capturing capacity, IL-CCS is currently the largest BECCS project in the world.

In addition to the IL-CCS project, there are about three more projects that capture CO2 from the ethanol plant at smaller scales. For example, Arkalon in Kansas, USA can capture 0.18-0.29 MtCO2/yr, OCAP in the Netherlands can capture about 0.1-0.3 MtCO2/yr, and Husky Energy in Canada can capture 0.09-0.1 MtCO2/yr.

At MSW recycling centers

Beside capturing CO2 from the ethanol plants, currently, there are 2 models in Europe are designed to capture CO2 from the processing of Municipal Solid Waste. The Klemetsrud Plant at Oslo, Norway use biogenic municipal solid waste to generate 175 GWh and capture 315 Ktonne of CO2 each year. It uses absorption technology with Aker Solution Advanced Amine solvent as a CO2 capture unit. Similarly, the ARV Duiven in the Netherlands uses the same technology, but it captures less CO2 than the previous model. ARV Duiven generates around 126 GWh and only capture 50 Ktonne of CO2 each year.

Techno-economics of BECCS and the TESBiC Project

The largest and most detailed techno-economic assessment of BECCS was carried out by cmcl innovations and the TESBiC group (Techno-Economic Study of Biomass to CCS) in 2012. This project recommended the most promising set of biomass fueled power generation technologies coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS). The project outcomes lead to a detailed “biomass CCS roadmap” for the U.K..

Challenges

Environmental considerations

Some of the environmental considerations and other concerns about the widespread implementation of BECCS are similar to those of CCS. However, much of the critique towards CCS is that it may strengthen the dependency on depletable fossil fuels and environmentally invasive coal mining. This is not the case with BECCS, as it relies on renewable biomass. There are however other considerations which involve BECCS and these concerns are related to the possible increased use of biofuels. Biomass production is subject to a range of sustainability constraints, such as: scarcity of arable land and fresh water, loss of biodiversity, competition with food production, deforestation and scarcity of phosphorus. It is important to make sure that biomass is used in a way that maximizes both energy and climate benefits. There has been criticism to some suggested BECCS deployment scenarios, where there would be a very heavy reliance on increased biomass input.

Large areas of land would be required to operate BECCS on an industrial scale. To remove 10 billion tonnes of CO2, upwards of 300 million hectares of land area (larger than India) would be required. As a result, BECCS risks using land that could be better suited to agriculture and food production, especially in developing countries.

These systems may have other negative side effects. There is however presently no need to expand the use of biofuels in energy or industry applications to allow for BECCS deployment. There is already today considerable emissions from point sources of biomass derived CO2, which could be utilized for BECCS. Though, in possible future bioenergy system upscaling scenarios, this may be an important consideration.

Upscaling BECCS would require a sustainable supply of biomass - one that does not challenge our land, water, and food security. Using bioenergy crops as feedstock will not only cause sustainability concerns but also require the use of more fertilizer leading to soil contamination and water pollution.[citation needed] Moreover, crop yield is generally subjected to climate condition, i.e. the supply of this bio-feedstock can be hard to control. Bioenergy sector must also expand to meet the supply level of biomass. Expanding bioenergy would require technical and economic development accordingly.

Technical challenges

A challenge for applying BECCS technology, as with other carbon capture and storage technologies, is to find suitable geographic locations to build combustion plant and to sequester captured CO2. If biomass sources are not close by the combustion unit, transporting biomass emits CO2 offsetting the amount of CO2 captured by BECCS. BECCS also face technical concerns about efficiency of burning biomass. While each type of biomass has a different heating value, biomass in general is a low-quality fuel. Thermal conversion of biomass typically has an efficiency of 20-27%. For comparison, coal-fired plants have an efficiency of about 37%.

BECCS also faces a question whether the process is actually energy positive. Low energy conversion efficiency, energy-intensive biomass supply, combined with the energy required to power the CO2 capture and storage unit impose energy penalty on the system. This might lead to a low power generation efficiency.

Potential solutions

Alternative biomass sources

Agricultural and forestry residues

Globally, 14 Gt of forestry residue and 4.4 Gt residues from crop production (mainly barley, wheat, corn, sugarcane and rice) are generated every year. This is a significant amount of biomass which can be combusted to generate 26 EJ/year and achieve a 2.8 Gt of negative CO2 emission through BECCS. Utilizing residues for carbon capture will provide social and economic benefits to rural communities. Using waste from crops and forestry is a way to avoid the ecological and social challenges of BECCS.

Municipal solid waste

Municipal solid waste (MSW) is one of the newly developed sources of biomass.Overview waste to energy techniques with CSS Two current BECCS plants are using MSW as feedstocks. Waste collected from daily life is recycled via incineration waste treatment process. Waste goes through high temperature thermal treatment and the heat generated from combusting organic part of waste is used to generate electricity. CO2emitted from this process is captured through absorption using MEA. For every 1 kg of waste combusted, 0.7 kg of negative CO2emission is achieved. Utilizing solid waste also have other environmental benefits.

Co-firing coal with biomass

As of 2017 there were roughly 250 cofiring plants in the world, including 40 in the US. Biomass cofiring with coal has efficiency near those of coal combustion. Instead of co-firing, full conversion from coal to biomass of one or more generating units in a plant may be preferred.

Policy

Based on the Kyoto Protocol agreement, carbon capture and storage projects were not applicable as an emission reduction tool to be used for the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or for Joint Implementation (JI) projects. Recognising CCS technologies as an emission reduction tool is vital for the implementation of such plants as there is no other financial motivation for the implementation of such systems. There has been growing support to have fossil CCS and BECCS included in the protocol as well as the current Paris Agreement. Accounting studies on how this can be implemented, including BECCS, have also been done.

European Union

There are some future policies that give incentives to use bioenergy such as Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and Fuel Quality Directive (FQD), which require 20% of total energy consumption to be based on biomass, bioliquids and biogas by 2020.

Sweden

The Swedish Energy Agency has been commissioned by the Swedish government to design a Swedish support system for BECCS to be implemented by 2022.

United Kingdom

In 2018 the Committee on Climate Change recommended that aviation biofuels should provide up to 10% of total aviation fuel demand by 2050, and that all aviation biofuels should be produced with CCS as soon as the technology is available.

United States

In 2018 the US congress significantly increased and extended the section 45Q tax credit for sequestration of carbon oxides. This has been a top priority of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) supporters for several years. It increased $25.70 to $50 tax credit per tonnes of CO2 for secure geological storage and $15.30 to $35 tax credit per tonne of CO2 used in enhanced oil recovery.

Public perception

Limited studies have investigated public perceptions of BECCS. Of those studies, most originate from developed countries in the northern hemisphere and therefore may not represent a worldwide view.

In a 2018 study involving online panel respondents from the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, and New Zealand, respondents showed little prior awareness of BECCS technologies. Measures of respondents perceptions suggest that the public associate BECCS with a balance of both positive and negative attributes. Across the four countries, 45% of the respondents indicated they would support small scale trials of BECCS, whereas only 21% were opposed. BECCS was moderately preferred among other methods of Carbon dioxide removal like Direct air capture or Enhanced weathering, and greatly preferred over methods of Solar radiation management.