From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Starting

from a young age, people can make moral decisions about what is right

and wrong. Moral reasoning, however, is a part of morality that occurs

both within and between individuals. Prominent contributors to this theory include Lawrence Kohlberg and Elliot Turiel.

The term is sometimes used in a different sense: reasoning under

conditions of uncertainty, such as those commonly obtained in a court of law. It is this sense that gave rise to the phrase, "To a moral certainty;" however, this idea is now seldom used outside of charges to juries.

Moral reasoning is an important and often daily process that

people use when trying to do the right thing. For instance, every day

people are faced with the dilemma of whether to lie in a given situation

or not. People make this decision by reasoning the morality of their

potential actions, and through weighing their actions against potential

consequences.

A moral choice can be a personal, economic, or ethical one; as described by some ethical code, or regulated by ethical relationships

with others. This branch of psychology is concerned with how these

issues are perceived by ordinary people, and so is the foundation of

descriptive ethics. There are many different forms of moral reasoning

which often are dictated by culture. Cultural differences in the

high-levels of cognitive function associated with moral reasoning can be

observed through the association of brain networks from various

cultures and their moral decision making. These cultural differences

demonstrate the neural basis that cultural influences can have on an

individual's moral reasoning and decision making.

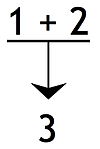

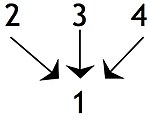

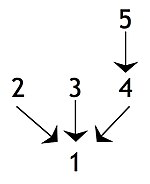

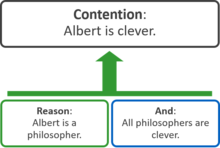

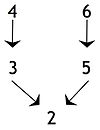

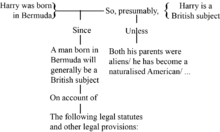

Distinctions between theories of moral reasoning can be accounted for by evaluating inferences (which tend to be either deductive or inductive) based on a given set of premises.

Deductive inference reaches a conclusion that is true based on whether a

given set of premises preceding the conclusion are also true, whereas,

inductive inference goes beyond information given in a set of premises

to base the conclusion on provoked reflection.

In philosophy

Philosopher David Hume claims that morality is based more on perceptions than on logical reasoning.

This means that people's morality is based more on their emotions and

feelings than on a logical analysis of any given situation. Hume regards

morals as linked to passion, love, happiness, and other emotions and

therefore not based on reason. Jonathan Haidt agrees, arguing in his social intuitionist model that reasoning concerning a moral situation or idea follows an initial intuition.

Haidt's fundamental stance on moral reasoning is that "moral intuitions

(including moral emotions) come first and directly cause moral

judgments"; he characterizes moral intuition as "the sudden appearance

in consciousness of a moral judgment, including an affective valence

(good-bad, like-dislike), without any conscious awareness of having gone

through steps of searching, weighing evidence, or inferring a

conclusion".

Immanuel Kant

had a radically different view of morality. In his view, there are

universal laws of morality that one should never break regardless of

emotions.

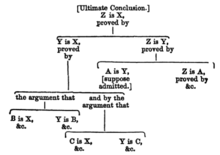

He proposes a four-step system to determine whether or not a given

action was moral based on logic and reason. The first step of this

method involves formulating "a maxim capturing your reason for an

action". In the second step, one "frame[s] it as a universal principle for all rational agents". The third step is assessing "whether a world based on this universal principle is conceivable". If it is, then the fourth step is asking oneself "whether [one] would will the maxim to be a principle in this world".

In essence, an action is moral if the maxim by which it is justified is

one which could be universalized. For instance, when deciding whether

or not to lie to someone for one's own advantage, one is meant to

imagine what the world would be like if everyone always lied, and

successfully so. In such a world, there would be no purpose in lying,

for everybody would expect deceit, rendering the universal maxim of

lying whenever it is to your advantage absurd. Thus, Kant argues that

one should not lie under any circumstance. Another example would be if

trying to decide whether suicide is moral or immoral; imagine if

everyone committed suicide. Since mass international suicide would not

be a good thing, the act of suicide is immoral. Kant's moral framework,

however, operates under the overarching maxim that you should treat each

person as an end in themselves, not as a means to an end. This

overarching maxim must be considered when applying the four

aforementioned steps.

Reasoning based on analogy

is one form of moral reasoning. When using this form of moral reasoning

the morality of one situation can be applied to another based on

whether this situation is relevantly similar: similar enough that the same moral reasoning applies. A similar type of reasoning is used in common law when arguing based upon legal precedent.

In consequentialism (often distinguished from deontology)

actions are based as right on wrong based upon the consequences of

action as opposed to a property intrinsic to the action itself.

In developmental psychology

Moral

reasoning first attracted a broad attention from developmental

psychologists in the mid-to-late 20th century. Their main theorization

involved elucidating the stages of development of moral reasoning

capacity.

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget

developed two phases of moral development, one common among children

and the other common among adults. The first is known as the

Heteronomous Phase.

This phase, more common among children, is characterized by the idea

that rules come from authority figures in one's life such as parents,

teachers, and God. It also involves the idea that rules are permanent no matter what.

Thirdly, this phase of moral development includes the belief that

"naughty" behavior must always be punished and that the punishment will

be proportional.

The second phase in Piaget's theory of moral development is

referred to as the Autonomous Phase. This phase is more common after

one has matured and is no longer a child. In this phase people begin to

view the intentions behind actions as more important than their

consequences.

For instance, if a person who is driving swerves in order to not hit a

dog and then knocks over a road sign, adults are likely to be less angry

at the person than if he or she had done it on purpose just for fun.

Even though the outcome is the same, people are more forgiving because

of the good intention of saving the dog. This phase also includes the

idea that people have different morals and that morality is not

necessarily universal. People in the Autonomous Phase also believe rules may be broken under certain circumstances. For instance, Rosa Parks

broke the law by refusing to give up her seat on a bus, which was

against the law but something many people consider moral nonetheless. In

this phase people also stop believing in the idea of immanent justice.

Lawrence Kohlberg

Inspired by Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg made significant contributions to the field of moral reasoning by creating a theory of moral development.

His theory is a "widely accepted theory that provides the basis for

empirical evidence on the influence of human decision making on ethical

behavior."

In Lawrence Kohlberg's view, moral development consists of the growth

of less egocentric and more impartial modes of reasoning on more

complicated matters. He believed that the objective of moral education

is the reinforcement of children to grow from one stage to an upper

stage. Dilemma was a critical tool that he emphasized that children

should be presented with; yet also, the knowledge for children to

cooperate.

According to his theory, people pass through three main stages of moral

development as they grow from early childhood to adulthood. These are

pre-conventional morality, conventional morality, and post-conventional

morality. Each of these is subdivided into two levels.

The first stage in the pre-conventional level is obedience and

punishment. In this stage people, usually young children, avoid certain

behaviors only because of the fear of punishment, not because they see

them as wrong.

The second stage in the pre-conventional level is called individualism

and exchange: in this stage people make moral decisions based on what

best serves their needs.

The third stage is part of the conventional morality level and is

called interpersonal relationships. In this stage one tries to conform

to what is considered moral by the society that they live in, attempting

to be seen by peers as a good person.

The fourth stage is also in the conventional morality level and is

called maintaining social order. This stage focuses on a view of

society as a whole and following the laws and rules of that society.

The fifth stage is a part of the post-conventional level and is

called social contract and individual rights. In this stage people begin

to consider differing ideas about morality in other people and feel

that rules and laws should be agreed on by the members of a society.

The sixth and final stage of moral development, the second in the

post-conventional level, is called universal principles. At this stage

people begin to develop their ideas of universal moral principles and

will consider them the right thing to do regardless of what the laws of a

society are.

James Rest

In

1983, James Rest developed the four component Model of Morality, which

addresses the ways that moral motivation and behavior occurs.

The first of these is moral sensitivity, which is "the ability to see

an ethical dilemma, including how our actions will affect others". The second is moral judgment, which is "the ability to reason correctly about what 'ought' to be done in a specific situation". The third is moral motivation, which is "a personal commitment to moral action, accepting responsibility for the outcome". The fourth and final component of moral behavior is moral character, which is a "courageous persistence in spite of fatigue or temptations to take the easy way out".

In social cognition

Based

on empirical results from behavioral and neuroscientific studies,

social and cognitive psychologists attempted to develop a more accurate descriptive (rather than normative) theory of moral reasoning.

That is, the emphasis of research was on how real-world individuals

made moral judgments, inferences, decisions, and actions, rather than

what should be considered as moral.

Dual-process theory and social intuitionism

Developmental theories of moral reasoning were critiqued as

prioritizing on the maturation of cognitive aspect of moral reasoning.

From Kohlberg's perspective, one is considered as more advanced in

moral reasoning as she is more efficient in using deductive reasoning

and abstract moral principles to make moral judgments about particular

instances. For instance, an advanced reasoner may reason syllogistically with the Kantian principle

of 'treat individuals as ends and never merely as means' and a

situation where kidnappers are demanding a ransom for a hostage, to

conclude that the kidnappers have violated a moral principle and should

be condemned. In this process, reasoners are assumed to be rational and

have conscious control over how they arrive at judgments and decisions.

In contrast with such view, however, Joshua Greene

and colleagues argued that laypeople's moral judgments are

significantly influenced, if not shaped, by intuition and emotion as

opposed to rational application of rules. In their fMRI studies in the

early 2000s,

participants were shown three types of decision scenarios: one type

included moral dilemmas that elicited emotional reaction (moral-personal

condition), the second type included moral dilemmas that did not elicit

emotional reaction (moral-impersonal condition), and the third type had

no moral content (non-moral condition). Brain regions such as posterior

cingulate gyrus and angular gyrus, whose activation is known to

correlate with experience of emotion, showed activations in

moral-personal condition but not in moral-impersonal condition.

Meanwhile, regions known to correlate with working memory, including

right middle frontal gyrus and bilateral parietal lobe, were less active

in moral-personal condition than in moral-impersonal condition.

Moreover, participants' neural activity in response to moral-impersonal

scenarios was similar to their activity in response to non-moral

decision scenarios.

Another study used variants of trolley problem

that differed in the 'personal/impersonal' dimension and surveyed

people's permissibility judgment (Scenarios 1 and 2). Across scenarios,

participants were presented with the option of sacrificing a person to

save five people. However, depending on the scenario, the sacrifice

involved pushing a person off a footbridge to block the trolley

(footbridge dilemma condition; personal) or simply throwing a switch to

redirect the trolley (trolley dilemma condition; impersonal). The

proportions of participants who judged the sacrifice as permissible

differed drastically: 11% (footbridge dilemma) vs. 89% (trolley

dilemma). This difference was attributed to the emotional reaction

evoked from having to apply personal force on the victim, rather than

simply throwing a switch without physical contact with the victim.

Focusing on participants who judged the sacrifice in trolley dilemma as

permissible but the sacrifice in footbridge dilemma as impermissible,

the majority of them failed to provide a plausible justification for

their differing judgments. Several philosophers have written critical responses on this matter to Joshua Greene and colleagues.

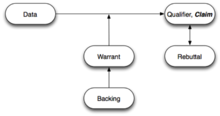

Based on these results, social psychologists proposed the dual process theory of morality.

They suggested that our emotional intuition and deliberate reasoning

are not only qualitatively distinctive, but they also compete in making

moral judgments and decisions. When making an emotionally-salient moral

judgment, automatic, unconscious, and immediate response is produced by

our intuition first. More careful, deliberate, and formal reasoning then

follows to produce a response that is either consistent or inconsistent

with the earlier response produced by intuition, in parallel with more general form of dual process theory of thinking.

But in contrast with the previous rational view on moral reasoning, the

dominance of the emotional process over the rational process was

proposed.

Haidt highlighted the aspect of morality not directly accessible by our

conscious search in memory, weighing of evidence, or inference. He

describes moral judgment as akin to aesthetic judgment, where an instant

approval or disapproval of an event or object is produced upon

perception.

Hence, once produced, the immediate intuitive response toward a

situation or person cannot easily be overridden by the rational

consideration that follows. The theory explained that in many cases,

people resolve inconsistency between the intuitive and rational

processes by using the latter for post-hoc justification of the former.

Haidt, using the metaphor "the emotional dog and its rational tail", applied such nature of our reasoning to the contexts ranging from person perception to politics.

A notable illustration of the influence of intuition involved feeling of disgust. According to Haidt's moral foundations theory,

political liberals rely on two dimensions (harm/care and

fairness/reciprocity) of evaluation to make moral judgments, but

conservatives utilize three additional dimensions (ingroup/loyalty,

authority/respect, and purity/sanctity).

Among these, studies have revealed the link between moral evaluations

based on purity/sanctity dimension and reasoner's experience of disgust.

That is, people with higher sensitivity to disgust were more likely to

be conservative toward political issues such as gay marriage and

abortion.

Moreover, when the researchers reminded participants of keeping the lab

clean and washing their hands with antiseptics (thereby priming the

purity/sanctity dimension), participants' attitudes were more

conservative than in the control condition. In turn, Helzer and Pizarro's findings have been rebutted by two failed attempts of replications.

Other studies raised criticism toward Haidt's interpretation of his data.

Augusto Blasi also rebuts the theories of Jonathan Haidt on moral

intuition and reasoning. He agrees with Haidt that moral intuition plays

a significant role in the way humans operate. However, Blasi suggests

that people use moral reasoning more than Haidt and other cognitive

scientists claim. Blasi advocates moral reasoning and reflection as the

foundation of moral functioning. Reasoning and reflection play a key

role in the growth of an individual and the progress of societies.

Alternatives to these dual-process/intuitionist models have been

proposed, with several theorists proposing that moral judgment and moral

reasoning involves domain general cognitive processes, e.g., mental

models, social learning or categorization processes.

Motivated reasoning

A theorization of moral reasoning similar to dual-process theory was

put forward with emphasis on our motivations to arrive at certain

conclusions. Ditto and colleagues

likened moral reasoners in everyday situations to lay attorneys than

lay judges; people do not reason in the direction from assessment of

individual evidence to moral conclusion (bottom-up), but from a

preferred moral conclusion to assessment of evidence (top-down). The

former resembles the thought process of a judge who is motivated to be

accurate, unbiased, and impartial in her decisions; the latter resembles

that of an attorney whose goal is to win a dispute using partial and

selective arguments.

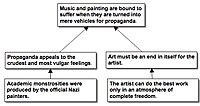

Kunda proposed motivated reasoning as a general framework for understanding human reasoning.

She emphasized the broad influence of physiological arousal, affect,

and preference (which constitute the essence of motivation and cherished

beliefs) on our general cognitive processes including memory search and

belief construction. Importantly, biases in memory search, hypothesis

formation and evaluation result in confirmation bias,

making it difficult for reasoners to critically assess their beliefs

and conclusions. It is reasonable to state that individuals and groups

will manipulate and confuse reasoning for belief depending on the lack

of self control to allow for their confirmation bias to be the driving

force of their reasoning. This tactic is used by media, government,

extremist groups, cults, etc. Those with a hold on information may dull

out certain variables that propagate their agenda and then leave out

specific context to push an opinion into the form of something

reasonable to control individual, groups, and entire populations. This

allows the use of alternative specific context with fringe content to

further veer from any form of dependability in their reasoning. Leaving a

fictional narrative in the place of real evidence for a logical outlook

to form a proper, honest, and logical assessment.

Applied to moral domain, our strong motivation to favor people we

like leads us to recollect beliefs and interpret facts in ways that

favor them. In Alicke (1992, Study 1),

participants made responsibility judgments about an agent who drove

over the speed limit and caused an accident. When the motive for

speeding was described as moral (to hide a gift for his parents'

anniversary), participants assigned less responsibility to the agent

than when the motive was immoral (to hide a vial of cocaine). Even

though the causal attribution of the accident may technically fall under

the domain of objective, factual understanding of the event, it was

nevertheless significantly affected by the perceived intention of the

agent (which was presumed to have determined the participants'

motivation to praise or blame him).

Another paper by Simon, Stenstrom, and Read (2015, Studies 3 and 4)

used a more comprehensive paradigm that measures various aspects of

participants' interpretation of a moral event, including factual

inferences, emotional attitude toward agents, and motivations toward the

outcome of decision. Participants read about a case involving a

purported academic misconduct and were asked to role-play as a judicial

officer who must provide a verdict. A student named Debbie had been

accused of cheating in an exam, but the overall situation of the

incident was kept ambiguous to allow participants to reason in a desired

direction. Then, the researchers attempted to manipulate participants'

motivation to support either the university (conclude that she cheated)

or Debbie (she did not cheat) in the case. In one condition, the

scenario stressed that through previous incidents of cheating, the

efforts of honest students have not been honored and the reputation of

the university suffered (Study 4, Pro-University condition); in another

condition, the scenario stated that Debbie's brother died from a tragic

accident a few months ago, eliciting participants' motivation to support

and sympathize with Debbie (Study 3, Pro-Debbie condition). Behavioral

and computer simulation results showed an overall shift in

reasoning--factual inference, emotional attitude, and moral

decision--depending on the manipulated motivation. That is, when the

motivation to favor the university/Debbie was elicited, participants'

holistic understanding and interpretation of the incident shifted in the

way that favored the university/Debbie. In these reasoning processes,

situational ambiguity was shown to be critical for reasoners to arrive

at their preferred conclusion.

From a broader perspective, Holyoak

and Powell interpreted motivated reasoning in the moral domain as a

special pattern of reasoning predicted by coherence-based reasoning

framework. This general framework of cognition, initially theorized by the philosopher Paul Thagard,

argues that many complex, higher-order cognitive functions are made

possible by computing the coherence (or satisfying the constraints)

between psychological representations such as concepts, beliefs, and

emotions.

Coherence-based reasoning framework draws symmetrical links between

consistent (things that co-occur) and inconsistent (things that do not

co-occur) psychological representations and use them as constraints,

thereby providing a natural way to represent conflicts between

irreconcilable motivations, observations, behaviors, beliefs, and

attitudes, as well as moral obligations.

Importantly, Thagard's framework was highly comprehensive in that it

provided a computational basis for modeling reasoning processes using

moral and non-moral facts and beliefs as well as variables related to

both 'hot' and 'cold' cognitions.

Causality and intentionality

Classical theories of social perception had been offered by psychologists including Fritz Heider (model of intentional action) and Harold Kelley (attribution theory).

These theories highlighted how laypeople understand another person's

action based on their causal knowledge of internal (intention and

ability of actor) and external (environment) factors surrounding that

action. That is, people assume a causal relationship between an actor's

disposition or mental states (personality, intention, desire, belief,

ability; internal cause), environment (external cause), and the

resulting action (effect). In later studies, psychologists discovered

that moral judgment toward an action or actor is critically linked with

these causal understanding and knowledge about the mental state of the

actor.

Bertram Malle and Joshua Knobe

conducted survey studies to investigate laypeople's understanding and

use (the folk concept) of the word 'intentionality' and its relation to

action.

His data suggested that people think of intentionality of an action in

terms of several psychological constituents: desire for outcome, belief

about the expected outcome, intention to act (combination of desire and

belief), skill to bring about the outcome, and awareness of action while

performing that action. Consistent with this view as well as with our

moral intuitions, studies found significant effects of the agent's

intention, desire, and beliefs on various types of moral judgments,

Using factorial designs to manipulate the content in the scenarios,

Cushman showed that the agent's belief and desire regarding a harmful

action significantly influenced judgments of wrongness, permissibility,

punishment, and blame. However, whether the action actually brought

about negative consequence or not only affected blame and punishment

judgments, but not wrongness and permissibility judgments. Another study also provided neuroscientific evidence for the interplay between theory of mind and moral judgment.

Through another set of studies, Knobe showed a significant effect

in the opposite direction: Intentionality judgments are significantly

affected by the reasoner's moral evaluation of the actor and action.

In one of his scenarios, a CEO of a corporation hears about a new

programme designed to increase profit. However, the program is also

expected to benefit or harm the environment as a side effect, to which

he responds by saying 'I don't care'. The side effect was judged as

intentional by the majority of participants in the harm condition, but

the response pattern was reversed in the benefit condition.

Many studies on moral reasoning have used fictitious scenarios involving anonymous strangers (e.g., trolley problem)

so that external factors irrelevant to researcher's hypothesis can be

ruled out. However, criticisms have been raised about the external

validity of the experiments in which the reasoners (participants) and

the agent (target of judgment) are not associated in any way.

As opposed to the previous emphasis on evaluation of acts, Pizarro and

Tannenbaum stressed our inherent motivation to evaluate the moral

characters of agents (e.g., whether an actor is good or bad), citing the

Aristotelian virtue ethics.

According to their view, learning the moral character of agents around

us must have been a primary concern for primates and humans beginning

from their early stages of evolution, because the ability to decide whom

to cooperate with in a group was crucial to survival.

Furthermore, observed acts are no longer interpreted separately from

the context, as reasoners are now viewed as simultaneously engaging in

two tasks: evaluation (inference) of moral character of agent and

evaluation of her moral act. The person-centered approach to moral

judgment seems to be consistent with results from some of the previous

studies that involved implicit character judgment. For instance, in

Alicke's (1992)

study, participants may have immediately judged the moral character of

the driver who sped home to hide cocaine as negative, and such inference

led the participants to assess the causality surrounding the incident

in a nuanced way (e.g., a person as immoral as him could have been

speeding as well).

In order to account for laypeople's understanding and use of

causal relations between psychological variables, Sloman, Fernbach, and

Ewing proposed a causal model of intentionality judgment based on Bayesian network.

Their model formally postulates that character of agent is a cause for

the agent's desire for outcome and belief that action will result in

consequence, desire and belief are causes for intention toward action,

and the agent's action is caused by both that intention and the skill

to produce consequence. Combining computational modeling with the ideas

from theory of mind

research, this model can provide predictions for inferences in

bottom-up direction (from action to intentionality, desire, and

character) as well as in top-down direction (from character, desire, and

intentionality to action).

Gender difference

At

one time psychologists believed that men and women have different moral

values and reasoning. This was based on the idea that men and women

often think differently and would react to moral dilemmas in different

ways. Some researchers hypothesized that women would favor care

reasoning, meaning that they would consider issues of need and

sacrifice, while men would be more inclined to favor fairness and

rights, which is known as justice reasoning.

However, some also knew that men and women simply face different moral

dilemmas on a day-to-day basis and that might be the reason for the

perceived difference in their moral reasoning.

With these two ideas in mind, researchers decided to do their

experiments based on moral dilemmas that both men and women face

regularly. To reduce situational differences and discern how both

genders use reason in their moral judgments, they therefore ran the

tests on parenting situations, since both genders can be involved in

child rearing.

The research showed that women and men use the same form of moral

reasoning as one another and the only difference is the moral dilemmas

they find themselves in on a day-to-day basis.

When it came to moral decisions both men and women would be faced

with, they often chose the same solution as being the moral choice. At

least this research shows that a division in terms of morality does not

actually exist, and that reasoning between genders is the same in moral

decisions.