A hotel describing a customer's opt-out of having sheets and towels washed as "joining the effort to save the environment"

Greenwashing (a compound word modelled on "whitewash"), also called "green sheen", is a form of spin in which green PR or green marketing is deceptively used to promote the perception that an organization's products, aims or policies are environmentally friendly.

Evidence that an organization is greenwashing often comes from pointing

out the spending differences: when significantly more money or time has

been spent advertising being "green" (that is, operating with consideration for the environment), than is actually spent on environmentally sound practices. Greenwashing efforts can range from changing the name or label of a product to evoke the natural environment

on a product that contains harmful chemicals to multimillion-dollar

advertising campaigns portraying highly polluting energy companies as

eco-friendly.

Publicized accusations of greenwashing have contributed to the term's increasing use.

While greenwashing is not new, its use has increased over recent years to meet consumer demand for environmentally friendly goods and services. The problem is compounded by lax enforcement by regulatory agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission in the United States, the Competition Bureau in Canada, and the Committee of Advertising Practice and the Broadcast Committee of Advertising Practice

in the United Kingdom. Critics of the practice suggest that the rise of

greenwashing, paired with ineffective regulation, contributes to

consumer skepticism of all green claims, and diminishes the power of the

consumer in driving companies toward greener solutions for

manufacturing processes and business operations.

Many corporate structures use greenwashing as a way to repair public

perception of their brand. The structuring of corporate disclosure is

often set up so as to maximize perceptions of legitimacy. However, a

growing body of social and environmental accounting research finds that,

in the absence of external monitoring a verification, greenwashing

strategies amount to corporate posturing and deception.

Usage

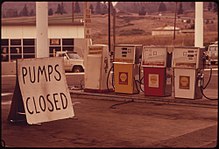

The term greenwashing was coined by New York environmentalist Jay Westervelt in a 1986 essay regarding the hotel industry's

practice of placing placards in each room promoting reuse of towels

ostensibly to "save the environment." Westervelt noted that, in most

cases, little or no effort toward reducing energy waste was being made

by these institutions—as evidenced by the lack of cost reduction this

practice effected. Westervelt opined that the actual objective of this

"green campaign" on the part of many hoteliers was, in fact, increased

profit. Westervelt thus labeled this and other outwardly environmentally

conscientious acts with a greater, underlying purpose of profit

increase as greenwashing.

In addition, the political term "linguistic detoxification" describes when, through legislation or other government action, the definitions of toxicity

for certain substances are changed, or the name of the substance is

changed, so that fewer things fall under a particular classification as

toxic. The origin of this phrase has been attributed to environmental

activist and author Barry Commoner.

Similarly, introduction of a Carbon Emission Trading Scheme

may feel good, but may be counterproductive if the cost of carbon is

priced too low, or if large emitters are given "free credits." For

example, Bank of America subsidiary MBNA offers an Eco-Logique MasterCard for Canadian consumers that rewards customers with carbon offsets as they continue using the card. Customers may feel that they are nullifying their carbon footprint

by purchasing polluting goods with the card. However, only 0.5 percent

of purchase price goes into purchasing carbon offsets, while the rest of

the interchange fee still goes to the bank.

Such campaigns and marketing communications,

designed to publicize and highlight organizational CSR policies to

various stakeholders, affect corporate reputation and brand image, but

the proliferation of unsubstantiated ethical claims and greenwashing by

some companies has resulted in increasing consumer cynicism and

mistrust.

History

In the

mid 1960s, the environmental movement gained momentum. This popularity

prompted many companies to create a new green image through advertising.

Jerry Mander, a former Madison Avenue advertising executive, called this new form of advertising "ecopornography."

The first Earth Day

was held on April 22, 1970. This encouraged many industries to

advertise themselves as being friendly to the environment. Public

utilities spent 300 million dollars advertising themselves as clean

green companies. This was eight times more than the money they spent on

pollution reduction research.

In 1985, the Chevron Corporation

launched one of the most famous greenwashing ad campaigns in history.

Chevron's "People Do" advertisements were aimed at a "hostile audience"

of "societally conscious" people. Two years after the launch of the

campaign, surveys found people in California trusted Chevron more than

other oil companies to protect the environment. In the late 1980s The American Chemistry Council started a program called Responsible Care,

which shone light on the environmental performances and precautions of

the group's members. The loose guidelines of responsible care caused

industries to adopt self-regulation over government regulation.

In 1991, a study published in the Journal of Public Policy and Marketing (American Marketing Association)

found that 58% of environmental ads had at least one deceptive claim.

Another study found that 77% of people said the environmental reputation

of company affected whether they would buy their products. One fourth

of all household products marketed around Earth Day advertised

themselves as being green and environmentally friendly. In 1998 the Federal Trade Commission

created the "Green Guidelines," which defined terms used in

environmental marketing. The following year the FTC found that the

Nuclear Energy Institute claims of being environmentally clean were not

true. The FTC did nothing about the ads because they were out of their

jurisdiction. This caused the FTC to realize they needed new clear

enforceable standards. In 1999, according to environmental activist

organizations, the word "greenwashing" was added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

In 2002, during the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, the Greenwashing Academy hosted the Greenwash Academy Awards. The ceremony awarded companies like BP, ExxonMobil, and even the US Government for their elaborate greenwashing ads and support for greenwashing.

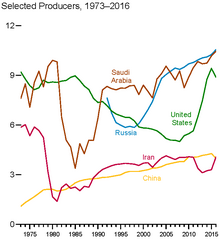

More recently, social scientists have been investigating claims

of and the impact of greenwashing. In 2005, Ramus and Monteil conducted

secondary data analysis of two databases to uncover corporate commitment

to implementation of environmental policies as opposed to greenwashing.

They found while companies in the oil and gas are more likely to implement environmental policies than service industry companies, they are less likely to commit to fossil fuel reduction.

In 2010 a study was done showing that 4.5% of products tested

were found to be truly green as opposed to 2% in 2009. In 2009 2,739

products claimed to be green while in 2010 the number rose to 4,744. The

same study in 2010 found that 95% percent of the consumer products

claiming to be green were not green at all.

Regulation

Australia

The Australian Trade Practices Act

has been modified to include punishment of companies that provide

misleading environmental claims. Any organization found guilty of such

could face up $6 million

in fines. In addition, the guilty party must pay for all expenses

incurred while setting the record straight about their product or

company's actual environmental impact.

Canada

Canada's Competition Bureau along with the Canadian Standards Association

are discouraging companies from making "vague claims" towards their

products' environmental impact. Any claims must be backed up by "readily

available data."

Norway

Norway's consumer ombudsman

has targeted automakers who claim that their cars are "green," "clean"

or "environmentally friendly" with some of the world's strictest

advertising guidelines. Consumer Ombudsman official Bente Øverli said:

"Cars cannot do anything good for the environment except less damage

than others." Manufacturers risk fines if they fail to drop the words.

Øverli said she did not know of other countries going so far in cracking

down on cars and the environment.

U.S.

The Federal Trade Commission

(FTC) provides voluntary guidelines for environmental marketing claims.

These guidelines give the FTC the right to prosecute false and

misleading advertisement claims. The green guidelines were not created

to be used as an enforceable guideline but instead were intended to be

followed voluntarily. Listed below are the green guidelines set by the

FTC.

- Qualifications and disclosures: The Commission traditionally has held that in order to be effective, any qualifications or disclosures such as those described in these guides should be sufficiently clear, prominent and understandable to prevent deception. Clarity of language, relative type size and proximity to the claim being qualified, and an absence of contrary claims that could undercut effectiveness, will maximize the likelihood that the qualifications and disclosures are appropriately clear and prominent.

- Distinction between benefits of product, package and service: An environmental marketing claim should be presented in a way that makes clear whether the environmental attribute or benefit being asserted refers to the product, the product's packaging, a service or to a portion or component of the product, package or service. In general, if the environmental attribute or benefit applies to all but minor, incidental components of a product or package, the claim need not be qualified to identify that fact. There may be exceptions to this general principle. For example, if an unqualified "recyclable" claim is made and the presence of the incidental component significantly limits the ability to recycle the product, then the claim would be deceptive.

- Overstatement of environmental attribute: An environmental marketing claim should not be presented in a manner that overstates the environmental attribute or benefit, expressly or by implication. Marketers should avoid implications of significant environmental benefits if the benefit is in fact negligible.

- Comparative claims: Environmental marketing claims that include a comparative statement should be presented in a manner that makes the basis for the comparison sufficiently clear to avoid consumer deception. In addition, the advertiser should be able to substantiate the comparison.

The FTC has said in 2010 that it will update its guidelines for

environmental marketing claims in an attempt to reduce greenwashing.

The revision to the FTC's Green Guides covers a wide range of public

input, including hundreds of consumer and industry comments on

previously proposed revisions. The updates and revision to the existing

Guides include a new section of carbon offsets, "green" certifications

and seals renewable energy and renewable materials claims. According to

FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz,

"The introduction of environmentally friendly products into the

marketplace is a win for consumers who want to purchase greener products

and producers who wants to sell them." Leibowitz also says the win-win

can only claim if marketers' claims are straightforward and proven.

In 2013, the FTC began enforcing the revisions put forth in the

Green Guides. The FTC cracked down on six different companies, in which

five of the cases were concerned with the false or misleading

advertising surrounding the biodegradability of plastics. The FTC

charged ECM Biofilms, American Plastic Manufacturing, CHAMP, Clear

Choice Housewares, and Carnie Cap, for misrepresenting the

biodegradability of their plastics treated with additives.

The FTC charged a sixth company, AJM Packaging Corporation, for

violating a commission consent order put in place that prohibits

companies from using advertising claims based on the product or

packaging being "degradable, biodegradable, or photodegradable" without

reliable scientific information.

The FTC now requires companies to disclose and provide the information

that qualifies their environmental claims to ensure transparency.

Examples

The Airbus A380 described as "A better environment inside and out."

- "Clean Burning Natural Gas" - When compared to the dirtiest fossil fuel coal, natural gas is only 50% as dirty. Fracking issues exist when producing the gas, and if as little as 3 percent of the gas produced escapes, effects upon the climate are close to equivalent as when burning coal. Despite this, it is often presented as a 'cleaner' fossil fuel in environmental discourse and is often used to balance the intermittent nature of solar and wind energy.

- Environmentalists have argued that the Bush Administration's Clear Skies Initiative actually weakens air pollution laws.

- Many food products have packaging that evokes an environmentally friendly imagery even though there has been no attempt made at lowering the environmental impact of its production.

- In 2009, European McDonald's changed the color of their logos from yellow and red to yellow and green; a spokesman for the company explained that the change was "to clarify [their] responsibility for the preservation of natural resources."

- Existing published consumption figures tend to underestimate the consumption seen in practice by 20 to 30%. The reason is partly that the official fuel consumption tests are not sufficiently representative of real world usage. Auto makers optimise their fuel consumption strategies in order to reduce the apparent cost of ownership of the cars, and to improve their green image.

- Some environmental conservation groups have criticized the Annenberg Foundation for their attempt to construct domestic pet adoption and care facilities in the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve by repackaging them as part of an "urban ecology center" - a name chosen because it "accommodated the animal adoption process" according to a former spokesperson for the Foundation. The Los Angeles Times called the proposed domestic pet adoption facilities a "bad fit" for the ecological reserve.

- An article in Wired magazine alleges that slogans are used to suggest environmentally benign business activity: the Comcast Ecobill has the slogan "PaperLESSisMORE", but Comcast uses large amounts of paper for direct marketing. The Poland Spring ecoshape bottle is touted as "A little natural does a lot of good," although 80% of beverage containers go to landfills. The Airbus A380 airliner is described as "A better environment inside and out" even though air travel has a high negative environment cost.

- The Advertising Standards Authority in the UK upheld several complaints against major car manufacturers including Suzuki, SEAT, Toyota and Lexus who made erroneous claims about their vehicles.

- Kimberly Clark's claim of "Pure and Natural" diapers in green packaging. The product uses organic cotton on the outside but keeps the same petrochemical gel on the inside. Pampers also claims that "Dry Max" diapers reduce landfill waste by reducing the amount of paper fluff in the diaper, which really is a way for Pampers to save money.

- A 2010 advertising campaign by Chevron was described by the Rainforest Action Network, Amazon Watch and The Yes Men as greenwash. A spoof campaign was launched to pre-empt Chevron's greenwashing.

- "Clean Coal," an initiative adopted by several platforms for the 2008 U.S presidential elections is an example of political greenwashing. The policy cited carbon capture as a means of reducing carbon emissions by capturing and injecting carbon dioxide produced by coal power plants into layers of porous rock below the ground. According to Fred Pearce's Greenwash column in The Guardian, "clean coal" is the "ultimate climate change oxymoron"—"pure and utter greenwash" he says.

- The conversion of the term "Tar Sands" to "Oil Sands," (Alberta, Canada) in corporate and political language reflects an ongoing debate between the project's adherents and opponents. This semantic shift can be seen as a case of greenwashing in an attempt at countering growing public concern as to the environmental and health impacts of the industry. While advocates claim that the shift is scientifically derived to better reflect the usage of the sands as a precursor to oil, environmental groups are claiming that this is simply a means of cloaking the issue behind friendlier terminology.

- Over the past years Walmart has proclaimed to "go green" with a sustainability campaign. However, according to the Institute For Local Reliance (ILRS), “Walmart’s sustainability campaign has done more to improve the company’s image than the environment.” Walmart still only generates 2 percent of U.S. electricity from wind and solar resources. According to the ILRS, Walmart routinely donates money to political candidates who vote against the environment. The retail giant responded to these accusations by stating "that it is serious about its commitment to reduce 20 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions by 2015".

- Environmental accounting can easily be used to pretend that environmental impacts of a company are reduced while actual impacts increase. This has been shown, for example, in a case of corporate carbon accounting: the company celebrated reduced relative emissions while absolute emissions increased. The same company achieved reducing current emissions by "correcting" past emissions as higher (effecting a calculation that presents current emissions as relatively lower).

- In 2018, in response to increased calls for banning plastic straws, Starbucks introduced a new straw-less lid that actually contained more plastic by weight than the old straw and lid combination.

Opposition

Organizations and individuals are making attempts to reduce the impact of greenwashing by exposing it to the public. The Greenwashing Index, created by the University of Oregon in partnership with EnviroMedia Social Marketing, allows examples of greenwashing to be uploaded and rated by the public.

The British Code of Advertising, Sales Promotion and Direct Marketing

has a specific section (section 49) targeting environmental claims.

According to some organizations opposing greenwashing, there has

been a significant increase in its use by companies over the last decade.

TerraChoice Environmental Marketing, an advertising consultancy

company, issued a report denoting a 79% increase in the usage of

corporate greenwashing between 2007 and 2009. Additionally, it has begun

to manifest itself in new varied ways. Within the non-residential

building products market in the United States, some companies are

beginning to claim that their environmentally minded policy changes will

allow them to earn points through the U.S. Green Building Council's

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design rating program. This point

system has been held up as an example of the "gateway effect" that the

drive to market products as environmentally friendly is having on

company policies. Some have claimed that the greenwashing trend may be

enough to eventually effect a genuine reduction in environmentally

damaging practices.

According to the Home and Family Edition, 95% consumer products

claiming to be green were discovered to commit at least one of the "Sins

of Greenwashing". The Seven Sins of Greenwashing are as follows:

- Sin of the Hidden Trade-off, committed by suggesting a product is "green" based on an unreasonably narrow set of attributes without attention to other important environmental issues.

- Sin of No Proof, committed by an environmental claim that cannot be substantiated by easily accessible supporting information or by a reliable third-party certification.

- Sin of Vagueness, committed by every claim that is so poorly defined or broad that its real meaning is likely to be misunderstood by the consumer.

- Sin of Worshiping False Labels is committed when a claim, communicated either through words or images, gives the impression of a third-party endorsement where no such endorsement exists.

- Sin of Irrelevance, committed by making an environmental claim that may be truthful but which is unimportant or unhelpful for consumers seeking environmentally preferable products.

- Sin of Lesser of Two Evils, committed by claims that may be true within the product category, but that risk distracting consumers from the greater environmental impact of the category as a whole.

- Sin of Fibbing, the least frequent Sin, is committed by making environmental claims that are simply false.

In 2008, Ed Gillespie identified "ten signs of greenwashing", which are similar to the Seven Sins listed above, but with three additional indicators.

- Suggestive pictures - Images that imply a baseless green impact, such as flowers issuing from the exhaust pipe of a vehicle.

- Just not credible - A claim that touts the environmentally friendly attributes of a dangerous product, such as cigarettes.

- Gobbledygook - The use of jargon or information that the average person can not readily understand or be able to verify.

Companies may pursue environmental certification to avoid greenwashing through independent verification of their green claims. For example, the Carbon Trust

Standard launched in 2007 with the stated aim "to end 'greenwash' and

highlight firms that are genuine about their commitment to the

environment".