|

Flag

| |

| |

| Headquarters | Vienna, Austria |

|---|---|

| Official language | English |

| Type | International cartel |

| Membership | |

| Leaders | |

| Mohammed Barkindo | |

| Establishment | Baghdad, Iraq |

• Statute

| September 1960 |

• In effect

| January 1961 |

| Currency | Indexed as USD per barrel (US$/bbl) |

Website

OPEC.org | |

The Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, /ˈoʊpɛk/ OH-pek) is an intergovernmental organisation of 15 nations, founded in 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), and headquartered since 1965 in Vienna, Austria. As of September 2018, the 15 countries accounted for an estimated 44 percent of global oil production and 81.5 percent of the world's "proven" oil reserves, giving OPEC a major influence on global oil prices that were previously determined by the so called "Seven Sisters” grouping of multinational oil companies.

The stated mission of the organization is to "coordinate and unify the petroleum policies of its member countries and ensure the stabilization of oil markets, in order to secure an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry." The organization is also a significant provider of information about the international oil market. The current OPEC members are the following: Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, the Republic of the Congo, Saudi Arabia (the de facto leader), United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela. Indonesia is a former member, and Qatar will no longer be a member of OPEC from 1 January 2019.. By continent, two are South American, seven African, and six are Asian (Middle East). Two-thirds of OPEC's oil production and reserves are in its six Middle-Eastern countries that surround the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

The formation of OPEC marked a turning point toward national sovereignty over natural resources, and OPEC decisions have come to play a prominent role in the global oil market and international relations. The effect can be particularly strong when wars or civil disorders lead to extended interruptions in supply. In the 1970s, restrictions in oil production led to a dramatic rise in oil prices and in the revenue and wealth of OPEC, with long-lasting and far-reaching consequences for the global economy. In the 1980s, OPEC began setting production targets for its member nations; generally, when the targets are reduced, oil prices increase. This has occurred most recently from the organization's 2008 and 2016 decisions to trim oversupply.

Economists often cite OPEC as a textbook example of a cartel that cooperates to reduce market competition, but one whose consultations are protected by the doctrine of state immunity under international law. In December 2014, "OPEC and the oil men" ranked as #3 on Lloyd's list of "the top 100 most influential people in the shipping industry". However, the influence of OPEC on international trade is periodically challenged by the expansion of non-OPEC energy sources, and by the recurring temptation for individual OPEC countries to exceed production targets and pursue conflicting self-interests.

Membership

Current member countries

As of June 2018, OPEC has 15 member countries: six in the Middle East (Western Asia), seven in Africa, and two in South America. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), OPEC's combined rate of oil production (including gas condensate) represented 44 percent of the world's total in 2016,

and OPEC accounted for 81.5 percent of the world's "proven" oil

reserves, including 48 percent from just the six Middle Eastern members.

.

Approval of a new member country requires agreement by

three-quarters of OPEC's existing members, including all five of the

founders. In October 2015, Sudan formally submitted an application to join, but it is not yet a member.

Qatar intends to leave OPEC on 1 January 2019.

| Country | Region | Membership Years | Population (2016 est.) |

Area (km2) |

Oil Production (bbl/day, 2016) |

Proven Reserves (bbl, 2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Africa | 1969– | 40,606,052 | 2,381,740 | 1,348,361 | 12,200,000,000 | |

| Southern Africa | 2007– | 28,813,463 | 1,246,700 | 1,769,615 | 8,423,000,000 | |

| South America | 1973–1992, 2007– | 16,385,068 | 283,560 | 548,421 | 8,273,000,000 | |

| Central Africa | 2017– | 1,221,490 | 28,051 | 227,000 | 1,100,000,000 | |

| Central Africa | 1975–1995, 2016– | 1,979,786 | 267,667 | 210,820 | 2,000,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1960– | 80,277,428 | 1,648,000 | 3,990,956 | 157,530,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1960– | 37,202,572 | 437,072 | 4,451,516 | 143,069,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1960– | 4,052,584 | 17,820 | 2,923,825 | 101,500,000,000 | |

| North Africa | 1962– | 6,293,253 | 1,759,540 | 384,686 | 48,363,000,000 | |

| West Africa | 1971– | 185,989,640 | 923,768 | 1,999,885 | 37,070,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1961–2019 | 2,569,804 | 11,437 | 1,522,902 | 25,244,000,000 | |

| Central Africa | 2018– | 5,125,821 | 342,000 | 260,000 | 1,600,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1960– | 32,275,687 | 2,149,690 | 10,460,710 | 266,578,000,000 | |

| Middle East | 1967– | 9,269,612 | 83,600 | 3,106,077 | 97,800,000,000 | |

| South America | 1960– | 31,568,179 | 912,050 | 2,276,967 | 299,953,000,000 | |

| OPEC Total | 483,630,000 | 12,492,695 | 35,481,740 | 1,210,703,000,000 | ||

| World Total | 7,673,493,000 | 510,072,000 | 80,622,287 | 1,650,585,000,000 | ||

| OPEC Percent | 6.3% | 2.4% | 44% | 73% | ||

One petroleum barrel (bbl) is approximately 42 U.S. gallons, or 159 liters, or 0.159 m3, varying slightly with temperature. To put the production numbers in context, a supertanker typically holds 2,000,000 barrels (320,000 m3), and the world's current production rate would take approximately 56 years to exhaust the world's current proven reserves.

The five founding members attended the first OPEC conference in September 1960.

The five founding members attended the first OPEC conference in September 1960.

The UAE was founded in December 1971. Its OPEC membership originated with the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.

Lapsed members

| Country | Region | Membership Years | Population (2016 est.) |

Area (km2) |

Oil Production (bbl/day, 2016) |

Proven Reserves (bbl, 2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast Asia | 1962–2008, Jan-Nov 2016 |

261,115,456 | 1,904,569 | 833,667 | 3,692,500,000 |

For countries that export petroleum at relatively low volume, their

limited negotiating power as OPEC members would not necessarily justify

the burdens imposed by OPEC production quotas and membership costs. Ecuador

withdrew from OPEC in December 1992, because it was unwilling to pay

the annual US$2 million membership fee and felt that it needed to

produce more oil than it was allowed under its OPEC quota at the time, although it rejoined in October 2007. Similar concerns prompted Gabon to suspend membership in January 1995; it rejoined in July 2016. In May 2008, Indonesia

announced that it would leave OPEC when its membership expired at the

end of that year, having become a net importer of oil and being unable

to meet its production quota. It rejoined the organization in January 2016, but announced another "temporary suspension" of its membership at year-end when OPEC requested a 5 percent production cut.

Some commentators consider that the United States was a de facto member of OPEC during its formal occupation of Iraq, due to its leadership of the Coalition Provisional Authority in 2003–2004. But this is not borne out by the minutes of OPEC meetings, as no US representative attended in an official capacity.

Observers

Since the 1980s, representatives from Egypt, Mexico, Norway, Oman, Russia,

and other oil-exporting nations have attended many OPEC meetings as

observers. This arrangement serves as an informal mechanism for

coordinating policies.

Leadership and decision-making

The OPEC Conference is the supreme authority of the organization, and

consists of delegations normally headed by the oil ministers of member

countries. The chief executive of the organization is the OPEC Secretary General.

The Conference ordinarily meets at the Vienna headquarters, at least

twice a year and in additional extraordinary sessions when necessary. It

generally operates on the principles of unanimity and "one member, one

vote", with each country paying an equal membership fee into the annual

budget.

However, since Saudi Arabia is by far the largest and most-profitable

oil exporter in the world, with enough capacity to function as the

traditional swing producer to balance the global market, it serves as "OPEC's de facto leader".

International cartel

At various times, OPEC members have displayed apparent anti-competitive cartel behavior through the organization's agreements about oil production and price levels.

In fact, economists often cite OPEC as a textbook example of a cartel

that cooperates to reduce market competition, as in this definition from

OECD's Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law:

International commodity agreements covering products such as coffee, sugar, tin and more recently oil (OPEC: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) are examples of international cartels which have publicly entailed agreements between different national governments.

OPEC members strongly prefer to describe their organization as a

modest force for market stabilization, rather than a powerful

anti-competitive cartel. In its defense, the organization was founded as

a counterweight against the previous "Seven Sisters"

cartel of multinational oil companies, and non-OPEC energy suppliers

have maintained enough market share for a substantial degree of

worldwide competition. Moreover, because of an economic "prisoner's dilemma" that encourages each member nation individually to discount its price and exceed its production quota, widespread cheating within OPEC often erodes its ability to influence global oil prices through collective action.

OPEC has not been involved in any disputes related to the competition rules of the World Trade Organization, even though the objectives, actions, and principles of the two organizations diverge considerably. A key US District Court decision held that OPEC consultations are protected as "governmental" acts of state by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, and are therefore beyond the legal reach of US competition law governing "commercial" acts. Despite popular sentiment against OPEC, legislative proposals to limit the organization's sovereign immunity, such as the NOPEC Act, have so far been unsuccessful.

Conflicts

OPEC

often has difficulty agreeing on policy decisions because its member

countries differ widely in their oil export capacities, production

costs, reserves, geological features, population, economic development,

budgetary situations, and political circumstances.

Indeed, over the course of market cycles, oil reserves can themselves

become a source of serious conflict, instability and imbalances, in what

economists call the "natural resource curse". A further complication is that religion-linked conflicts in the Middle East are recurring features of the geopolitical landscape for this oil-rich region. Internationally important conflicts in OPEC's history have included the Six-Day War (1967), Yom Kippur War (1973), a hostage siege directed by Palestinian militants (1975), the Iranian Revolution (1979), Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), Iraqi occupation of Kuwait (1990–1991), September 11 attacks by mostly Saudi hijackers (2001), American occupation of Iraq (2003–2011), Conflict in the Niger Delta (2004–present), Arab Spring (2010–2012), Libyan Crisis (2011–present), and international Embargo against Iran

(2012–2016). Although events such as these can temporarily disrupt oil

supplies and elevate prices, the frequent disputes and instabilities

tend to limit OPEC's long-term cohesion and effectiveness.

Market information

As

one area in which OPEC members have been able to cooperate productively

over the decades, the organization has significantly improved the

quality and quantity of information available about the international

oil market. This is especially helpful for a natural-resource industry

whose smooth functioning requires months and years of careful planning.

Publications and research

Logo for JODI, in which OPEC is a founding member

In April 2001, OPEC collaborated with five other international organizations (APEC, Eurostat, IEA, OLADE, UNSD)

to improve the availability and reliability of oil data. They launched

the Joint Oil Data Exercise, which in 2005 was joined by IEF and renamed the Joint Organisations Data Initiative (JODI), covering more than 90 percent of the global oil market. GECF joined as an eighth partner in 2014, enabling JODI also to cover nearly 90 percent of the global market for natural gas.

Since 2007, OPEC has published the "World Oil Outlook" (WOO)

annually, in which it presents a comprehensive analysis of the global

oil industry including medium- and long-term projections for supply and

demand. OPEC also produces an "Annual Statistical Bulletin" (ASB), and publishes more-frequent updates in its "Monthly Oil Market Report" (MOMR) and "OPEC Bulletin".

Crude oil benchmarks

Sulfur content and API gravity of different types of crude oil

A "crude oil benchmark" is a standardized petroleum

product that serves as a convenient reference price for buyers and

sellers of crude oil, including standardized contracts in major futures markets

since 1983. Benchmarks are used because oil prices differ (usually by a

few dollars per barrel) based on variety, grade, delivery date and

location, and other legal requirements.

The OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes has been an important benchmark for oil prices since 2000. It is calculated as a weighted average

of prices for petroleum blends from the OPEC member countries: Saharan

Blend (Algeria), Girassol (Angola), Oriente (Ecuador), Rabi Light

(Gabon), Iran Heavy (Islamic Republic of Iran), Basra Light (Iraq),

Kuwait Export (Kuwait), Es Sider (Libya), Bonny Light (Nigeria), Qatar

Marine (Qatar), Arab Light (Saudi Arabia), Murban (UAE), and Merey

(Venezuela).

North Sea Brent Crude Oil

is the leading benchmark for Atlantic basin crude oils, and is used to

price approximately two-thirds of the world's traded crude oil. Other

well-known benchmarks are West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Dubai Crude, Oman Crude, and Urals oil.

Spare capacity

The

US Energy Information Administration, the statistical arm of the US

Department of Energy, defines spare capacity for crude oil market

management "as the volume of production that can be brought on within 30

days and sustained for at least 90 days... OPEC spare capacity provides

an indicator of the world oil market's ability to respond to potential

crises that reduce oil supplies."

In November 2014, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated

that OPEC's "effective" spare capacity, adjusted for ongoing

disruptions in countries like Libya and Nigeria, was 3.5 million barrels

per day (560,000 m3/d) and that this number would increase to a peak in 2017 of 4.6 million barrels per day (730,000 m3/d).

By November 2015, the IEA changed its assessment "with OPEC's spare

production buffer stretched thin, as Saudi Arabia – which holds the

lion's share of excess capacity – and its [Persian] Gulf neighbours pump

at near-record rates."

History and impact

Post-WWII situation

In 1949, Venezuela and Iran took the earliest steps in the direction of OPEC, by inviting Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to improve communication among petroleum-exporting nations as the world recovered from World War II. At the time, some of the world's largest oil fields were just entering production in the Middle East. The United States had established the Interstate Oil Compact Commission to join the Texas Railroad Commission

in limiting overproduction. The US was simultaneously the world's

largest producer and consumer of oil; and the world market was dominated

by a group of multinational companies known as the "Seven Sisters", five of which were headquartered in the US following the breakup of John D. Rockefeller's original Standard Oil

monopoly. Oil-exporting countries were eventually motivated to form

OPEC as a counterweight to this concentration of political and economic

power.

1959–1960 anger from exporting countries

In

February 1959, as new supplies were becoming available, the

multinational oil companies (MOCs) unilaterally reduced their posted

prices for Venezuelan and Middle Eastern crude oil by 10 percent. Weeks

later, the Arab League's first Arab Petroleum Congress convened in Cairo, Egypt, where the influential journalist Wanda Jablonski introduced Saudi Arabia's Abdullah Tariki to Venezuela's observer Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo,

representing the two then-largest oil-producing nations outside the

United States and the Soviet Union. Both oil ministers were angered by

the price cuts, and the two led their fellow delegates to establish the

Maadi Pact or Gentlemen's Agreement, calling for an "Oil Consultation

Commission" of exporting countries, to which MOCs should present

price-change plans. Jablonski reported a marked hostility toward the

West and a growing outcry against "absentee landlordism"

of the MOCs, which at the time controlled all oil operations within the

exporting countries and wielded enormous political influence. In August

1960, ignoring the warnings, and with the US favoring Canadian and

Mexican oil for strategic reasons, the MOCs again unilaterally announced

significant cuts in their posted prices for Middle Eastern crude oil.

1960–1975 founding and expansion

OPEC headquarters in Vienna

(2009 building)

(2009 building)

The following month, during 10–14 September 1960, the Baghdad

Conference was held at the initiative of Tariki, Pérez Alfonzo, and

Iraqi prime minister Abd al-Karim Qasim, whose country had skipped the 1959 congress. Government representatives from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela met in Baghdad

to discuss ways to increase the price of crude oil produced by their

countries, and ways to respond to unilateral actions by the MOCs.

Despite strong US opposition: "Together with Arab and non-Arab

producers, Saudi Arabia formed the Organization of Petroleum Export

Countries (OPEC) to secure the best price available from the major oil

corporations."

The Middle Eastern members originally called for OPEC headquarters to

be in Baghdad or Beirut, but Venezuela argued for a neutral location,

and so the organization chose Geneva, Switzerland. On 1 September 1965, OPEC moved to Vienna, Austria, after Switzerland declined to extend diplomatic privileges.

During 1961–1975, the five founding nations were joined by Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962–2008, rejoined 2014-2016), Libya (1962), United Arab Emirates (originally just the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, 1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973–1992, rejoined 2007), and Gabon (1975–1994, rejoined 2016). By the early 1970s, OPEC's membership accounted for more than half of worldwide oil production. Indicating that OPEC is not averse to further expansion, Mohammed Barkindo, OPEC's Acting Secretary General in 2006, urged his African neighbors Angola and Sudan to join, and Angola did in 2007, followed by Equatorial Guinea in 2017.

Since the 1980s, representatives from Egypt, Mexico, Norway, Oman,

Russia, and other oil-exporting nations have attended many OPEC meetings

as observers, as an informal mechanism for coordinating policies.

1973–1974 oil embargo

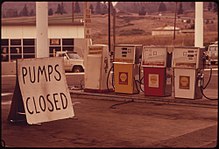

An undersupplied US gasoline station, closed during the oil embargo in 1973

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC, consisting of the Arab majority of OPEC plus Egypt and Syria) declared significant production cuts and an oil embargo against the United States and other industrialized nations that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. A previous embargo attempt was largely ineffective in response to the Six-Day War in 1967.

However, in 1973, the result was a sharp rise in oil prices and OPEC

revenues, from US$3/bbl to US$12/bbl, and an emergency period of energy rationing, intensified by panic reactions, a declining trend in US oil production, currency devaluations, and a lengthy UK coal-miners dispute. For a time, the UK imposed an emergency three-day workweek. Seven European nations banned non-essential Sunday driving.

US gas stations limited the amount of gasoline that could be dispensed,

closed on Sundays, and restricted the days when gasoline could be

purchased, based on license plate numbers.

Even after the embargo ended in March 1974 following intense diplomatic

activity, prices continued to rise. The world experienced a global economic recession, with unemployment and inflation surging simultaneously, steep declines in stock and bond prices, major shifts in trade balances and petrodollar flows, and a dramatic end to the post-WWII economic boom.

The 1973–1974 oil embargo had lasting effects on the United States and other industrialized nations, which established the International Energy Agency in response, as well as national emergency stockpiles designed to withstand months of future supply disruptions. Oil conservation efforts included lower speed limits on highways, smaller and more energy-efficient cars and appliances, year-round daylight saving time, reduced usage of heating and air-conditioning, better insulation, increased support of mass transit, and greater emphasis on coal, natural gas, ethanol, nuclear and other alternative energy

sources. These long-term efforts became effective enough that US oil

consumption would rise only 11 percent during 1980–2014, while real GDP

rose 150 percent. But in the 1970s, OPEC nations demonstrated

convincingly that their oil could be used as both a political and

economic weapon against other nations, at least in the short term.

1975–1980 Special Fund, now OFID

OPEC's international aid activities date from well before the 1973–1974 oil price surge. For example, the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development has operated since 1961.

In the years after 1973, as an example of so-called "checkbook diplomacy", certain Arab nations have been among the world's largest providers of foreign aid,

and OPEC added to its goals the selling of oil for the socio-economic

growth of poorer nations. The OPEC Special Fund was conceived in Algiers, Algeria,

in March 1975, and was formally established the following January. "A

Solemn Declaration 'reaffirmed the natural solidarity which unites OPEC

countries with other developing countries in their struggle to overcome

underdevelopment,' and called for measures to strengthen cooperation

between these countries... [The OPEC Special Fund's] resources are

additional to those already made available by OPEC states through a

number of bilateral and multilateral channels." The Fund became an official international development agency in May 1980 and was renamed the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), with Permanent Observer status at the United Nations.

1975 hostage siege

On 21 December 1975, Saudi Arabia's Ahmed Zaki Yamani, Iran's Jamshid Amuzegar, and the other OPEC oil ministers were taken hostage at their semi-annual conference in Vienna, Austria. The attack, which killed three non-ministers, was orchestrated by a six-person team led by Venezuelan militant "Carlos the Jackal", and which included Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann and Hans-Joachim Klein. The self-named "Arm of the Arab Revolution" group declared its goal to be the liberation of Palestine.

Carlos planned to take over the conference by force and hold for ransom

all eleven attending oil ministers, except for Yamani and Amuzegar who

were to be executed.

Carlos arranged bus and plane travel for his team and 42 of the original 63 hostages, with stops in Algiers and Tripoli, planning to fly eventually to Baghdad,

where Yamani and Amuzegar were to be killed. All 30 non-Arab hostages

were released in Algiers, excluding Amuzegar. Additional hostages were

released at another stop in Tripoli before returning to Algiers. With

only 10 hostages remaining, Carlos held a phone conversation with

Algerian President Houari Boumédienne,

who informed Carlos that the oil ministers' deaths would result in an

attack on the plane. Boumédienne must also have offered Carlos asylum at

this time and possibly financial compensation for failing to complete

his assignment. Carlos expressed his regret at not being able to murder

Yamani and Amuzegar, then he and his comrades left the plane. All the

hostages and terrorists walked away from the situation, two days after

it began.

Some time after the attack, Carlos's accomplices revealed that the operation was commanded by Wadie Haddad, a founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. They also claimed that the idea and funding came from an Arab president, widely thought to be Muammar al-Gaddafi of Libya, itself an OPEC member. Fellow militants Bassam Abu Sharif

and Klein claimed that Carlos received and kept a ransom between

US$20 million and US$50 million from "an Arab president". Carlos claimed

that Saudi Arabia paid ransom on behalf of Iran, but that the money was

"diverted en route and lost by the Revolution". He was finally captured in 1994 and is serving life sentences for at least 16 other murders.

1979–1980 oil crisis and 1980s oil glut

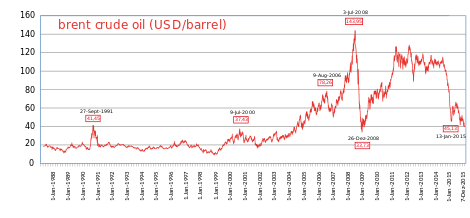

Fluctuations of OPEC net oil export revenues since 1972

In response to a wave of oil nationalizations

and the high prices of the 1970s, industrial nations took steps to

reduce their dependence on OPEC oil, especially after prices reached new

peaks approaching US$40/bbl in 1979–1980 when the Iranian Revolution and Iran–Iraq War

disrupted regional stability and oil supplies. Electric utilities

worldwide switched from oil to coal, natural gas, or nuclear power; national governments initiated multibillion-dollar research programs to develop alternatives to oil; and commercial exploration developed major non-OPEC oilfields in Siberia, Alaska, the North Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico. By 1986, daily worldwide demand for oil dropped by 5 million barrels, non-OPEC production rose by an even-larger amount, and OPEC's market share sank from approximately 50 percent in 1979 to less than 30 percent in 1985.

Illustrating the volatile multi-year timeframes of typical market

cycles for natural resources, the result was a six-year decline in the

price of oil, which culminated by plunging more than half in 1986 alone.

As one oil analyst summarized succinctly: "When the price of something

as essential as oil spikes, humanity does two things: finds more of it

and finds ways to use less of it."

To combat falling revenue from oil sales, in 1982 Saudi Arabia pressed OPEC for audited national production quotas

in an attempt to limit output and boost prices. When other OPEC nations

failed to comply, Saudi Arabia first slashed its own production from

10 million barrels daily in 1979–1981 to just one-third of that level in

1985. When even this proved ineffective, Saudi Arabia reversed course

and flooded the market with cheap oil, causing prices to fall below

US$10/bbl and higher-cost producers to become unprofitable. Faced with increasing economic hardship (which ultimately contributed to the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989), the "free-riding"

oil exporters that had previously failed to comply with OPEC agreements

finally began to limit production to shore up prices, based on

painstakingly negotiated national quotas that sought to balance

oil-related and economic criteria since 1986.

(Within their sovereign-controlled territories, the national

governments of OPEC members are able to impose production limits on both

government-owned and private oil companies.) Generally when OPEC production targets are reduced, oil prices increase.

1990–2003 ample supply and modest disruptions

One of the hundreds of Kuwaiti oil fires set by retreating Iraqi troops in 1991

Fluctuations of Brent crude oil price, 1988–2015

Leading up to his August 1990 Invasion of Kuwait, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein

was pushing OPEC to end overproduction and to send oil prices higher,

in order to help OPEC members financially and to accelerate rebuilding

from the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq War.

But these two Iraqi wars against fellow OPEC founders marked a low

point in the cohesion of the organization, and oil prices subsided

quickly after the short-term supply disruptions. The September 2001 Al Qaeda attacks on the US and the March 2003 US invasion of Iraq

had even milder short-term impacts on oil prices, as Saudi Arabia and

other exporters again cooperated to keep the world adequately supplied.

In the 1990s, OPEC lost its two newest members, who had joined in

the mid-1970s. Ecuador withdrew in December 1992, because it was

unwilling to pay the annual US$2 million membership fee and felt that it

needed to produce more oil than it was allowed under the OPEC quota, although it rejoined in October 2007. Similar concerns prompted Gabon to suspend membership in January 1995; it rejoined in July 2016.

Iraq has remained a member of OPEC since the organization's founding,

but Iraqi production was not a part of OPEC quota agreements from 1998

to 2016, due to the country's daunting political difficulties.

Lower demand triggered by the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis

saw the price of oil fall back to 1986 levels. After oil slumped to

around US$10/bbl, joint diplomacy achieved a gradual slowing of oil

production by OPEC, Mexico and Norway.

After prices slumped again in Nov. 2001, OPEC, Norway, Mexico, Russia,

Oman and Angola agreed to cut production on 1 Jan. 2002 for 6 months.

OPEC contributed 1.5 million barrels a day (mbpd) to the approximately 2

mbpd of cuts announced.

In June 2003, the International Energy Agency

(IEA) and OPEC held their first joint workshop on energy issues. They

have continued to meet regularly since then, "to collectively better

understand trends, analysis and viewpoints and advance market

transparency and predictability."

2003–2011 volatility

Widespread insurgency and sabotage occurred during the 2003–2008 height of the American occupation of Iraq, coinciding with rapidly increasing oil demand from China and commodity-hungry investors, recurring violence against the Nigerian oil industry, and dwindling spare capacity as a cushion against potential shortages. This combination of forces prompted a sharp rise in oil prices to levels far higher than those previously targeted by OPEC.

Price volatility reached an extreme in 2008, as WTI crude oil surged to

a record US$147/bbl in July and then plunged back to US$32/bbl in

December, during the worst global recession since World War II.

OPEC's annual oil export revenue also set a new record in 2008,

estimated around US$1 trillion, and reached similar annual rates in

2011–2014 (along with extensive petrodollar recycling activity) before plunging again. By the time of the 2011 Libyan Civil War and Arab Spring, OPEC started issuing explicit statements to counter "excessive speculation" in oil futures markets, blaming financial speculators for increasing volatility beyond market fundamentals.

In May 2008, Indonesia announced that it would leave OPEC when

its membership expired at the end of that year, having become a net

importer of oil and being unable to meet its production quota.

A statement released by OPEC on 10 September 2008 confirmed Indonesia's

withdrawal, noting that OPEC "regretfully accepted the wish of

Indonesia to suspend its full membership in the organization, and

recorded its hope that the country would be in a position to rejoin the

organization in the not-too-distant future."

2008 production dispute

Countries by net oil exports (2008)

The differing economic needs of OPEC member states often affect the

internal debates behind OPEC production quotas. Poorer members have

pushed for production cuts from fellow members, to increase the price of

oil and thus their own revenues.

These proposals conflict with Saudi Arabia's stated long-term strategy

of being a partner with the world's economic powers to ensure a steady

flow of oil that would support economic expansion.

Part of the basis for this policy is the Saudi concern that overly

expensive oil or unreliable supply will drive industrial nations to

conserve energy and develop alternative fuels, curtailing the worldwide

demand for oil and eventually leaving unneeded barrels in the ground. To this point, Saudi Oil Minister Yamani famously remarked in 1973: "The Stone Age didn't end because we ran out of stones."

On 10 September 2008, with oil prices still near US$100/bbl, a

production dispute occurred when the Saudis reportedly walked out of a

negotiating session where rival members voted to reduce OPEC output.

Although Saudi delegates officially endorsed the new quotas, they stated

anonymously that they would not observe them. The New York Times

quoted one such delegate as saying: "Saudi Arabia will meet the

market's demand. We will see what the market requires and we will not

leave a customer without oil. The policy has not changed." Over the next few months, oil prices plummeted into the $30s, and did not return to $100 until the Libyan Civil War in 2011.

2014–2017 oil glut

Countries by oil production (2013)

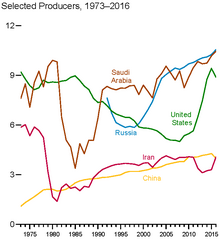

Top oil-producing countries (million barrels per day, 1973–2016)

Gusher well in Saudi Arabia: conventional source of OPEC production

Shale "fracking" in the US: important new challenge to OPEC market share

During 2014–2015, OPEC members consistently exceeded their production

ceiling, and China experienced a slowdown in economic growth. At the

same time, US oil production nearly doubled from 2008 levels and

approached the world-leading "swing producer" volumes of Saudi Arabia and Russia, due to the substantial long-term improvement and spread of shale "fracking"

technology in response to the years of record oil prices. These

developments led in turn to a plunge in US oil import requirements

(moving closer to energy independence), a record volume of worldwide oil inventories, and a collapse in oil prices that continued into early 2016.

In spite of global oversupply, on 27 November 2014 in Vienna, Saudi Oil Minister Ali Al-Naimi

blocked appeals from poorer OPEC members for production cuts to support

prices. Naimi argued that the oil market should be left to rebalance

itself competitively at lower price levels, strategically rebuilding

OPEC's long-term market share by ending the profitability of high-cost

US shale oil production. As he explained in an interview:

Is it reasonable for a highly efficient producer to reduce output, while the producer of poor efficiency continues to produce? That is crooked logic. If I reduce, what happens to my market share? The price will go up and the Russians, the Brazilians, US shale oil producers will take my share... We want to tell the world that high-efficiency producing countries are the ones that deserve market share. That is the operative principle in all capitalist countries... One thing is for sure: Current prices [roughly US$60/bbl] do not support all producers.

A year later, when OPEC met in Vienna on 4 December 2015, the

organization had exceeded its production ceiling for 18 consecutive

months, US oil production had declined only slightly from its peak,

world markets appeared to be oversupplied by at least 2 million barrels

per day despite war-torn Libya pumping 1 million barrels below capacity,

oil producers were making major adjustments to withstand prices as low

as the $40s, Indonesia was rejoining the export organization, Iraqi

production had surged after years of disorder, Iranian output was poised

to rebound with the lifting of international sanctions, hundreds of world leaders at the Paris Climate Agreement were committing to limit carbon emissions from fossil fuels, and solar technologies

were becoming steadily more competitive and prevalent. In light of all

these market pressures, OPEC decided to set aside its ineffective

production ceiling until the next ministerial conference in June 2016.

By 20 January 2016, the OPEC Reference Basket was down to US$22.48/bbl –

less than one-fourth of its high from June 2014 ($110.48), less than

one-sixth of its record from July 2008 ($140.73), and back below the

April 2003 starting point ($23.27) of its historic run-up.

As 2016 continued, the oil glut was partially trimmed with

significant production offline in the US, Canada, Libya, Nigeria and

China, and the basket price gradually rose back into the $40s. OPEC

regained a modest percentage of market share, saw the cancellation of

many competing drilling projects, maintained the status quo at its June

conference, and endorsed "prices at levels that are suitable for both

producers and consumers", although many producers were still

experiencing serious economic difficulties.

2017–2018 production cut

As OPEC members grew weary of a multi-year supply contest with diminishing returns

and shrinking financial reserves, the organization finally attempted

its first production cut since 2008. Despite many political obstacles, a

September 2016 decision to trim approximately 1 million barrels per day

was codified by a new quota agreement at the November 2016 OPEC

conference. The agreement (which exempted disruption-ridden members

Libya and Nigeria) covered the first half of 2017 – alongside promised

reductions from Russia and ten other non-members, offset by expected

increases in the US shale sector, Libya, Nigeria, spare capacity,

and surging late-2016 OPEC production before the cuts took effect.

Indonesia announced another "temporary suspension" of its OPEC

membership, rather than accepting the organization's requested 5 percent

production cut. Prices fluctuated around US$50/bbl, and OPEC in May

2017 decided to extend the new quotas through March 2018, with the world

waiting to see if and how the oil inventory glut might be fully

siphoned-off by then. Longtime oil analyst Daniel Yergin

"described the relationship between OPEC and shale as 'mutual

coexistence', with both sides learning to live with prices that are

lower than they would like."

In December 2017, Russia and OPEC agreed to extend the production cut of 1.8million barrels/day until the end of 2018.

Qatar announced it will withdraw from OPEC effective 1st of January 2019. According to the New York Times, this constitutes a strategic response to the ongoing Qatar boycott by Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt.