| Yellow fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Yellow jack, yellow plague, bronze john |

| |

| A TEM micrograph of yellow fever virus (234,000× magnification) | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, chills, muscle pain, headache, yellow skin |

| Complications | Liver failure, bleeding |

| Usual onset | 3–6 days post exposure |

| Duration | 3–4 days |

| Causes | Yellow fever virus spread by mosquitoes |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test |

| Prevention | Yellow fever vaccine |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

| Frequency | ~127,000 severe cases (2013) |

| Deaths | 5,100 (2015) |

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains particularly in the back, and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is increased.

The disease is caused by yellow fever virus and is spread by the bite of an infected female mosquito. It infects only humans, other primates, and several types of mosquitoes. In cities, it is spread primarily by Aedes aegypti, a type of mosquito found throughout the tropics and subtropics. The virus is an RNA virus of the genus Flavivirus. The disease may be difficult to tell apart from other illnesses, especially in the early stages. To confirm a suspected case, blood-sample testing with polymerase chain reaction is required.

A safe and effective vaccine against yellow fever exists, and some countries require vaccinations for travelers. Other efforts to prevent infection include reducing the population of the transmitting mosquitoes. In areas where yellow fever is common, early diagnosis of cases and immunization of large parts of the population are important to prevent outbreaks. Once infected, management is symptomatic with no specific measures effective against the virus. Death occurs in up to half of those who get severe disease.

In 2013, yellow fever resulted in about 127,000 severe infections and 45,000 deaths, with nearly 90 percent of these occurring in African nations. Nearly a billion people live in an area of the world where the disease is common. It is common in tropical areas of the continents of South America and Africa, but not in Asia. Since the 1980s, the number of cases of yellow fever has been increasing. This is believed to be due to fewer people being immune, more people living in cities, people moving frequently, and changing climate increasing the habitat for mosquitoes. The disease originated in Africa and spread to South America with the slave trade in the 17th century. Since the 17th century, several major outbreaks of the disease have occurred in the Americas, Africa, and Europe. In the 18th and 19th centuries, yellow fever was seen as one of the most dangerous infectious diseases. In 1927, yellow fever virus became the first human virus to be isolated.

Signs and symptoms

Yellow fever begins after an incubation period of three to six days.

Most cases only cause a mild infection with fever, headache, chills,

back pain, fatigue, loss of appetite, muscle pain, nausea, and vomiting. In these cases, the infection lasts only three to four days.

In 15% of cases, though, people enter a second, toxic phase of

the disease with recurring fever, this time accompanied by jaundice due

to liver damage, as well as abdominal pain. Bleeding in the mouth, nose, the eyes, and the gastrointestinal tract cause vomit containing blood, hence the Spanish name for yellow fever, vómito negro ("black vomit"). There may also be kidney failure, hiccups, and delirium.

Among those who develop jaundice, the fatality rate is 20 to 50%, while the overall fatality rate is about 5%. Severe cases may have a mortality greater than 50%.

Surviving the infection provides lifelong immunity, and normally no permanent organ damage results.

Cause

| Yellow fever virus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | incertae sedis |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Flavivirus |

| Species: |

Yellow fever virus

|

Yellow fever is caused by yellow fever virus, an enveloped RNA virus 40–50 nm in width, the type species and namesake of the family Flaviviridae. It was the first illness shown to be transmissible by filtered human serum and transmitted by mosquitoes, by Walter Reed around 1900. The positive-sense, single-stranded RNA is around 11,000 nucleotides long and has a single open reading frame encoding a polyprotein. Host proteases

cut this polyprotein into three structural (C, prM, E) and seven

nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5); the

enumeration corresponds to the arrangement of the protein coding genes in the genome. Minimal yellow fever virus

(YFV) 3'UTR region is required for stalling of the host 5'-3'

exonuclease XRN1. The UTR contains PKS3 pseudoknot structure, which

serves as a molecular signal to stall the exonuclease and is the only

viral requirement for subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) production. The

sfRNAs are a result of incomplete degradation of the viral genome by the

exonuclease and are important for viral pathogenicity. Yellow fever belongs to the group of hemorrhagic fevers.

The viruses infect, amongst others, monocytes, macrophages, Schwann cells, and dendritic cells. They attach to the cell surfaces via specific receptors and are taken up by an endosomal vesicle. Inside the endosome, the decreased pH induces the fusion of the endosomal membrane with the virus envelope. The capsid enters the cytosol, decays, and releases the genome. Receptor binding, as well as membrane fusion, are catalyzed by the protein E, which changes its conformation at low pH, causing a rearrangement of the 90 homodimers to 60 homotrimers.

After entering the host cell, the viral genome is replicated in the rough endoplasmic reticulum

(ER) and in the so-called vesicle packets. At first, an immature form

of the virus particle is produced inside the ER, whose M-protein is not

yet cleaved to its mature form, so is denoted as precursor M (prM) and

forms a complex with protein E. The immature particles are processed in

the Golgi apparatus by the host protein furin, which cleaves prM to M. This releases E from the complex, which can now take its place in the mature, infectious virion.

Transmission

Aedes aegypti feeding

Adults of the yellow fever mosquito A. aegypti: The male is on the left, females are on the right. Only the female mosquito bites humans to transmit the disease.

Yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti, but other mostly Aedes mosquitoes such as the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) can also serve as a vector for this virus. Like other arboviruses, which are transmitted by mosquitoes, yellow fever virus

is taken up by a female mosquito when it ingests the blood of an

infected human or another primate. Viruses reach the stomach of the

mosquito, and if the virus concentration is high enough, the virions can

infect epithelial cells and replicate there. From there, they reach the haemocoel (the blood system of mosquitoes) and from there the salivary glands.

When the mosquito next sucks blood, it injects its saliva into the

wound, and the virus reaches the bloodstream of the bitten person. Transovarial and transstadial transmission of yellow fever virus within A. aegypti,

that is, the transmission from a female mosquito to her eggs and then

larvae, are indicated. This infection of vectors without a previous

blood meal seems to play a role in single, sudden breakouts of the

disease.

Three epidemiologically different infectious cycles occur in which the virus is transmitted from mosquitoes to humans or other primates. In the "urban cycle", only the yellow fever mosquito A. aegypti is involved. It is well adapted to urban areas, and can also transmit other diseases, including Zika fever, dengue fever, and chikungunya.

The urban cycle is responsible for the major outbreaks of yellow fever

that occur in Africa. Except for an outbreak in Bolivia in 1999, this

urban cycle no longer exists in South America.

Besides the urban cycle, both in Africa and South America, a sylvatic cycle (forest or jungle cycle) is present, where Aedes africanus (in Africa) or mosquitoes of the genus Haemagogus and Sabethes

(in South America) serve as vectors. In the jungle, the mosquitoes

infect mainly nonhuman primates; the disease is mostly asymptomatic in

African primates. In South America, the sylvatic cycle is currently the

only way humans can become infected, which explains the low incidence of

yellow fever cases on the continent. People who become infected in the

jungle can carry the virus to urban areas, where A. aegypti acts

as a vector. Because of this sylvatic cycle, yellow fever cannot be

eradicated except by eradicating the mosquitoes that serve as vectors.

In Africa, a third infectious cycle known as "savannah cycle" or

intermediate cycle, occurs between the jungle and urban cycles.

Different mosquitoes of the genus Aedes are involved. In recent years, this has been the most common form of transmission of yellow fever in Africa.

Concern exists about yellow fever spreading to southeast Asia, where its vector A. aegypti already occurs.

Pathogenesis

After transmission from a mosquito, the viruses replicate in the lymph nodes and infect dendritic cells in particular. From there, they reach the liver and infect hepatocytes (probably indirectly via Kupffer cells), which leads to eosinophilic degradation of these cells and to the release of cytokines. Apoptotic masses known as Councilman bodies appear in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes.

Diagnosis

Yellow fever is most frequently a clinical diagnosis,

made from symptoms and where the infected person was before becoming

ill. Mild courses of the disease can only be confirmed virologically.

Since mild courses of yellow fever can also contribute significantly to

regional outbreaks, every suspected case of yellow fever (involving

symptoms of fever, pain, nausea, and vomiting 6–10 days after leaving

the affected area) is treated seriously.

If yellow fever is suspected, the virus cannot be confirmed until

6–10 days after the illness. A direct confirmation can be obtained by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, where the genome of the virus is amplified. Another direct approach is the isolation of the virus and its growth in cell culture using blood plasma; this can take 1–4 weeks.

Serologically, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay during the acute phase of the disease using specific IgM against yellow fever or an increase in specific IgG titer

(compared to an earlier sample) can confirm yellow fever. Together with

clinical symptoms, the detection of IgM or a four-fold increase in IgG

titer is considered sufficient indication for yellow fever. Since these

tests can cross-react with other flaviviruses, such as dengue virus, these indirect methods cannot conclusively prove yellow fever infection.

Liver biopsy can verify inflammation and necrosis of hepatocytes and detect viral antigens. Because of the bleeding tendency of yellow fever patients, a biopsy is only advisable post mortem to confirm the cause of death.

In a differential diagnosis, infections with yellow fever must be distinguished from other feverish illnesses such as malaria. Other viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola virus, Lassa virus, Marburg virus, and Junin virus, must be excluded as the cause.

Prevention

Personal

prevention of yellow fever includes vaccination and avoidance of

mosquito bites in areas where yellow fever is endemic. Institutional

measures for prevention of yellow fever include vaccination programmes

and measures of controlling mosquitoes. Programmes for distribution of

mosquito nets for use in homes are providing reductions in cases of both

malaria and yellow fever. Use of EPA-registered insect repellent is

recommended when outdoors. Exposure for even a short time is enough for a

potential mosquito bite. Long-sleeved clothing, long pants, and socks

are useful for prevention. The application of larvicides to

water-storage containers can help eliminate potential mosquito breeding

sites. EPA-registered insecticide spray decreases the transmission of

yellow fever.

- Use insect repellent when outdoors such as those containing DEET, picaridin, ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535), or oil of lemon eucalyptus on exposed skin.

- Wear proper clothing to reduce mosquito bites. When weather permits, wear long sleeves, long pants, and socks when outdoors. Mosquitoes may bite through thin clothing, so spraying clothes with repellent containing permethrin or another EPA-registered repellent gives extra protection. Clothing treated with permethrin is commercially available. Mosquito repellents containing permethrin are not approved for application directly to the skin.

- The peak biting times for many mosquito species are dusk to dawn. However, A. aegypti, one of the mosquitoes that transmits yellow fever virus, feeds during the daytime. Staying in accommodations with screened or air-conditioned rooms, particularly during peak biting times, also reduces the risk of mosquito bites.

Vaccination

The cover of a certificate that confirms the holder has been vaccinated against yellow fever

Vaccination

is recommended for those traveling to affected areas, because

non-native people tend to develop more severe illness when infected.

Protection begins by the 10th day after vaccine administration in 95% of

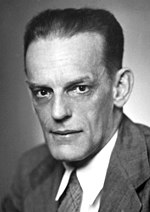

people, and had been reported to last for at least 10 years. The World Health Organization (WHO) now states that a single dose of vaccination is sufficient to confer lifelong immunity against yellow fever disease." The attenuated live vaccine stem 17D was developed in 1937 by Max Theiler. The WHO recommends routine vaccinations for people living in affected areas between the 9th and 12th month after birth.

Up to one in four people experience fever, aches, and local soreness and redness at the site of injection. In rare cases (less than one in 200,000 to 300,000),

the vaccination can cause yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic

disease, which is fatal in 60% of cases. It is probably due to the

genetic morphology of the immune system. Another possible side effect is

an infection of the nervous system, which occurs in one in 200,000 to

300,000 cases, causing yellow fever vaccine-associated neurotropic

disease, which can lead to meningoencephalitis and is fatal in less than 5% of cases.

The Yellow Fever Initiative, launched by the WHO in 2006,

vaccinated more than 105 million people in 14 countries in West Africa.[36] No outbreaks were reported during 2015. The campaign was supported by the GAVI Alliance,

and governmental organizations in Europe and Africa. According to the

WHO, mass vaccination cannot eliminate yellow fever because of the vast

number of infected mosquitoes in urban areas of the target countries,

but it will significantly reduce the number of people infected.

Demand for the yellow fever vaccine has continued to increase due

to the growing number of countries implementing yellow fever

vaccination as part of their routine immunization programmes.

Recent upsurges in yellow fever outbreaks in Angola (2015), the

Democratic Republic of Congo (2016), Uganda (2016), and more recently in

Nigeria and Brazil in 2017 have further increased demand, while

straining global vaccine supply.

Therefore, to vaccinate susceptible populations in preventive mass

immunization campaigns during outbreaks, fractional dosing of the

vaccine is being considered as a dose-sparing strategy to maximize

limited vaccine supplies.

Fractional dose yellow fever vaccination refers to administration of a

reduced volume of vaccine dose, which has been reconstituted as per

manufacturer recommendations.

The first practical use of fractional dose yellow fever vaccination was

in response to a large yellow fever outbreak in the Democratic Republic

of the Congo in mid-2016.

In March 2017, the WHO launched a vaccination campaign in Brazil with 3.5 million doses from an emergency stockpile. In March 2017 the WHO recommended vaccination for travellers to certain parts of Brazil.

In March 2018, Brazil shifted its policy and announced it planned to

vaccinate all 77.5 million currently unvaccinated citizens by April

2019.

Compulsory vaccination

Some

countries in Asia are theoretically in danger of yellow fever epidemics

(mosquitoes with the capability to transmit yellow fever and

susceptible monkeys are present), although the disease does not yet

occur there. To prevent introduction of the virus, some countries demand

previous vaccination of foreign visitors if they have passed through

yellow fever areas. Vaccination has to be proved by the production of a

vaccination certificate, which is valid 10 days after the vaccination

and lasts for 10 years. Although the WHO on 17 May 2013 advised that

subsequent booster vaccinations are unnecessary, an older (than 10

years) certificate may not be acceptable at all border posts in all

affected countries. A list of the countries that require yellow fever

vaccination is published by the WHO.

If the vaccination cannot be conducted for some reasons, dispensation

may be possible. In this case, an exemption certificate issued by a

WHO-approved vaccination center is required. Although 32 of 44 countries

where yellow fever occurs endemically do have vaccination programmes,

in many of these countries, less than 50% of their population is

vaccinated.

Vector control

Control of the yellow fever mosquito A. aegypti is of major importance, especially because the same mosquito can also transmit dengue fever and chikungunya disease. A. aegypti

breeds preferentially in water, for example in installations by

inhabitants of areas with precarious drinking water supply, or in

domestic waste, especially tires, cans, and plastic bottles. These

conditions are common in urban areas in developing countries.

Two main strategies are employed to reduce mosquito populations.

One approach is to kill the developing larvae. Measures are taken to

reduce the water accumulations in which the larvae develop. Larvicides are used, as well as larvae-eating fish and copepods, which reduce the number of larvae. For many years, copepods of the genus Mesocyclops have been used in Vietnam

for preventing dengue fever. It eradicated the mosquito vector in

several areas. Similar efforts may be effective against yellow fever. Pyriproxyfen is recommended as a chemical larvicide, mainly because it is safe for humans and effective even in small doses.

The second strategy is to reduce populations of the adult yellow fever mosquito. Lethal ovitraps can reduce Aedes

populations, but with a decreased amount of pesticide because it

targets the mosquitoes directly. Curtains and lids of water tanks can be

sprayed with insecticides, but application inside houses is not

recommended by the WHO. Insecticide-treated mosquito nets are effective, just as they are against the Anopheles mosquito that carries malaria.

Treatment

As for other Flavivirus

infections, no cure is known for yellow fever. Hospitalization is

advisable and intensive care may be necessary because of rapid

deterioration in some cases. Different methods for acute treatment of

the disease have been shown not to be very successful; passive

immunization after the emergence of symptoms is probably without effect.

Ribavirin and other antiviral drugs, as well as treatment with interferons, do not have a positive effect in patients. Asymptomatic treatment includes rehydration and pain relief with drugs such as paracetamol. Acetylsalicylic acid

should not be given because of its anticoagulant effect, which can be

devastating in the case of internal bleeding that can occur with yellow

fever.

Epidemiology

Yellow fever is common

in tropical and subtropical areas of South America and Africa.

Worldwide, about 600 million people live in endemic areas. The WHO

estimates 200,000 cases of disease and 30,000 deaths a year occur. But

the number of officially reported cases is far lower.

Africa

Areas with risk of yellow fever in Africa (2017)

An estimated 90% of the infections occur on the African continent. In 2008, the largest number of recorded cases was in Togo. In 2016, a large outbreak originated in Angola

and spread to neighboring countries before being contained by a massive

vaccination campaign. In March and April 2016, 11 cases were reported

in China, the first appearance of the disease in Asia in recorded

history.

Phylogenetic analysis has identified seven genotypes of yellow fever viruses, and they are assumed to be differently adapted to humans and to the vector A. aegypti.

Five genotypes (Angola, Central/East Africa, East Africa, West Africa

I, and West Africa II) occur only in Africa. West Africa genotype I is

found in Nigeria and the surrounding areas.

This appears to be especially virulent or infectious, as this type is

often associated with major outbreaks. The three genotypes in East and

Central Africa occur in areas where outbreaks are rare. Two recent

outbreaks in Kenya (1992–1993) and Sudan (2003 and 2005) involved the

East African genotype, which had remained unknown until these outbreaks

occurred.

South America

Areas with risk of yellow fever in South America (2018)

In South America, two genotypes have been identified (South American genotypes I and II). Based on phylogenetic analysis these two genotypes appear to have originated in West Africa and were first introduced into Brazil. The date of introduction into South America appears to be 1822 (95% confidence interval 1701 to 1911).

The historical record shows an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in

Recife, Brazil, between 1685 and 1690. The disease seems to have

disappeared, with the next outbreak occurring in 1849. It was likely

introduced with the importation of slaves through the slave trade from Africa. Genotype I has been divided into five subclades, A through E.

In late 2016, a large outbreak began in Minas Gerais state of Brazil that was characterized as a sylvan or jungle epizootic. It began as an outbreak in brown howler monkeys, which serve as a sentinel species for yellow fever, that then spread to men working in the jungle. No cases had been transmitted between humans by the A. aegypti

mosquito, which can sustain urban outbreaks that can spread rapidly. In

April 2017, the sylvan outbreak continued moving toward the Brazilian

coast, where most people were unvaccinated.

By the end of May the outbreak appeared to be declining after more than

3,000 suspected cases, 758 confirmed and 264 deaths confirmed to be

yellow fever. The Health Ministry launched a vaccination campaign and was concerned about spread during the Carnival season in February and March. The CDC issued a Level 2 alert (practice enhanced precautions.)

A Bayesian analysis of genotypes I and II has shown that genotype I accounts for virtually all the current infections in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Trinidad and Tobago, while genotype II accounted for all cases in Peru.

Genotype I originated in the northern Brazilian region around 1908 (95%

highest posterior density interval [HPD]: 1870–1936). Genotype II

originated in Peru in 1920 (95% HPD: 1867–1958). The estimated rate of

mutation for both genotypes was about 5 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year, similar to that of other RNA viruses.

Asia

The main vector (A. aegypti)

also occurs in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, the Pacific,

and Australia, but yellow fever has never occurred there, until jet

travel introduced 11 cases from the 2016 Angola and DR Congo yellow fever outbreak in Africa. Proposed explanations include:

- That the strains of the mosquito in the east are less able to transmit yellow fever virus.

- That immunity is present in the populations because of other diseases caused by related viruses (for example, dengue).

- That the disease was never introduced because the shipping trade was insufficient.

But none is considered satisfactory. Another proposal is the absence of a slave trade to Asia on the scale of that to the Americas. The trans-Atlantic slave trade probably introduced yellow fever into the Western Hemisphere from Africa.

History

Early history

The

evolutionary origins of yellow fever most likely lie in Africa, with

transmission of the disease from nonhuman primates to humans.

The virus is thought to have originated in East or Central Africa and

spread from there to West Africa. As it was endemic in Africa, the

natives had developed some immunity to it. When an outbreak of yellow

fever would occur in an African village where colonists resided, most

Europeans died, while the native population usually suffered nonlethal

symptoms resembling influenza.

This phenomenon, in which certain populations develop immunity to

yellow fever due to prolonged exposure in their childhood, is known as acquired immunity. The virus, as well as the vector A. aegypti, were probably transferred to North and South America with the importation of slaves from Africa, part of the Columbian Exchange following European exploration and colonization.

The first definitive outbreak of yellow fever in the New World was in 1647 on the island of Barbados. An outbreak was recorded by Spanish colonists in 1648 in the Yucatán Peninsula, where the indigenous Mayan people called the illness xekik ("blood vomit"). In 1685, Brazil suffered its first epidemic in Recife. The first mention of the disease by the name "yellow fever" occurred in 1744. McNeill argues that the environmental and ecological disruption caused by the introduction of sugar plantations created the conditions for mosquito and viral reproduction, and subsequent outbreaks of yellow fever. Deforestation reduced populations of insectivorous birds and other creatures that fed on mosquitoes and their eggs.

Sugar curing house, 1762: Sugar pots and jars on sugar plantations served as breeding place for larvae of A. aegypti, the vector of yellow fever.

In Colonial times and during the Napoleonic Wars,

the West Indies were known as a particularly dangerous posting for

soldiers due to yellow fever being endemic in the area. The mortality

rate in British garrisons in Jamaica was seven times that of garrisons in Canada, mostly because of yellow fever and other tropical diseases.

Both English and French forces posted there were seriously affected by

the "yellow jack." Wanting to regain control of the lucrative sugar

trade in Saint-Domingue

(Hispaniola), and with an eye on regaining France's New World empire,

Napoleon sent an army under the command of his brother-in-law General Charles Leclerc

to Saint-Domingue to seize control after a slave revolt. The historian

J. R. McNeill asserts that yellow fever accounted for about 35,000 to

45,000 casualties of these forces during the fighting.

Only one third of the French troops survived for withdrawal and return

to France. Napoleon gave up on the island and his plans for North

America, selling the Louisiana Purchase to the US in 1803. In 1804, Haiti

proclaimed its independence as the second republic in the Western

Hemisphere. Considerable debate exists over whether the number of deaths

caused by disease in the Haitian Revolution was exaggerated.

Although yellow fever is most prevalent in tropical-like

climates, the northern United States were not exempted from the fever.

The first outbreak in English-speaking North America occurred in New York City in 1668. English colonists in Philadelphia and the French in the Mississippi River Valley recorded major outbreaks in 1669, as well as additional yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York City in the 18th and 19th centuries. The disease traveled along steamboat routes from New Orleans, causing some 100,000–150,000 deaths in total. The yellow fever epidemic of 1793

in Philadelphia, which was then the capital of the United States,

resulted in the deaths of several thousand people, more than 9% of the

population. The national government fled the city, including President George Washington.

Headstones of people who died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 can be found in New Orleans' cemeteries.

The southern city of New Orleans

was plagued with major epidemics during the 19th century, most notably

in 1833 and 1853. Its residents called the disease "yellow jack." Urban

epidemics continued in the United States until 1905, with the last

outbreak affecting New Orleans.

At least 25 major outbreaks took place in the Americas during the

18th and 19th centuries, including particularly serious ones in Cartagena, Chile, in 1741; Cuba in 1762 and 1900; Santo Domingo in 1803; and Memphis, Tennessee, in 1878.

In the early nineteenth century, the prevalence of yellow fever

in the Caribbean "led to serious health problems" and alarmed the United States Navy as numerous deaths and sickness curtailed naval operations and destroyed morale. A tragic episode began in April of 1822 when the frigate USS Macedonian left Boston and became part of Commodore James Biddle's West India Squadron. Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson

had assigned the squadron to guard United States merchant shipping and

suppress piracy. During their time on deployment from 26 May to 3 August

1822, seventy-six of the Macedonian's officers and men died, including

Dr. John Cadle, Surgeon USN. Seventy-four of these deaths were

attributed to yellow fever. Biddle reported that another fifty-two of

his crew were on sick-list. In their report to the Secretary of the

Navy, Biddle and Surgeon's Mate Dr. Charles Chase stated the cause as

"fever." As a consequence of this loss, Biddle noted that his squadron

was forced to return to Norfolk Navy Yard early. Upon arrival, the

Macedonian's crew were provided medical care and quarantined at Craney

Island, Virginia.

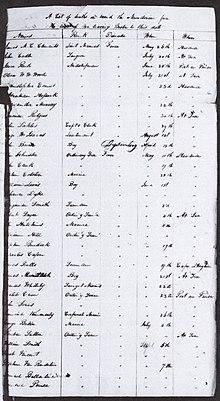

A

page from Commodore James Biddle's list of the seventy-six dead

(seventy-four of yellow fever) aboard the USS Macedonian, dated 3 August

1822

In 1853, Cloutierville, Louisiana,

had a late-summer outbreak of yellow fever that quickly killed 68 of

the 91 inhabitants. A local doctor concluded that some unspecified

infectious agent had arrived in a package from New Orleans. In 1854, 650 residents of Savannah, Georgia died from yellow fever. In 1858, St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church in Charleston, South Carolina, suffered 308 yellow fever deaths, reducing the congregation by half. A ship carrying persons infected with the virus arrived in Hampton Roads in southeastern Virginia in June 1855. The disease spread quickly through the community, eventually killing over 3,000 people, mostly residents of Norfolk and Portsmouth. In 1873, Shreveport, Louisiana,

lost 759 citizens in an 80-day period to a yellow fever epidemic, with

over 400 additional victims eventually succumbing. The total death toll

from August through November was approximately 1,200.

In 1878, about 20,000 people died in a widespread epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley.

That year, Memphis had an unusually large amount of rain, which led to

an increase in the mosquito population. The result was a huge epidemic

of yellow fever.

The steamship John D. Porter took people fleeing Memphis northward in

hopes of escaping the disease, but passengers were not allowed to

disembark due to concerns of spreading yellow fever. The ship roamed the

Mississippi River for the next two months before unloading her

passengers.

Major outbreaks have also occurred in southern Europe. Gibraltar lost many lives to outbreaks in 1804, 1814, and 1828. Barcelona suffered the loss of several thousand citizens during an outbreak in 1821. The Duke de Richelieu deployed 30,000 French troops to the border between France and Spain in the Pyrenees Mountains, to establish a cordon sanitaire in order to prevent the epidemic from spreading from Spain into France.

Causes and transmission

Ezekiel Stone Wiggins, known as the Ottawa Prophet, proposed that the cause of a yellow fever epidemic in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1888, was astrological.

The planets were in the same line as the sun and earth and this produced, besides Cyclones, Earthquakes, etc., a denser atmosphere holding more carbon and creating microbes. Mars had an uncommonly dense atmosphere, but its inhabitants were probably protected from the fever by their newly discovered canals, which were perhaps made to absorb carbon and prevent the disease.

In 1848, Josiah C. Nott

suggested that yellow fever was spread by insects such as moths or

mosquitoes, basing his ideas on the pattern of transmission of the

disease. Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor and scientist, proposed in 1881 that yellow fever might be transmitted by mosquitoes rather than direct human contact. Since the losses from yellow fever in the Spanish–American War in the 1890s were extremely high, Army doctors began research experiments with a team led by Walter Reed, and composed of doctors James Carroll, Aristides Agramonte, and Jesse William Lazear.

They successfully proved Finlay's ″mosquito hypothesis″. Yellow fever

was the first virus shown to be transmitted by mosquitoes. The physician

William Gorgas applied these insights and eradicated yellow fever from Havana. He also campaigned against yellow fever during the construction of the Panama Canal.

A previous effort of canal building by the French had failed in part

due to mortality from the high incidence of yellow fever and malaria,

which killed many workers.

Although Dr. Walter Reed has received much of the credit in

United States history books for "beating" yellow fever, he had fully

credited Dr. Finlay with the discovery of the yellow fever vector, and

how it might be controlled. Reed often cited Finlay's papers in his own

articles, and also credited him for the discovery in his personal

correspondence. The acceptance of Finlay's work was one of the most important and far-reaching effects of the Walter Reed Commission of 1900.

Applying methods first suggested by Finlay, the United States

government and Army eradicated yellow fever in Cuba and later in Panama,

allowing completion of the Panama Canal. While Reed built on the

research of Finlay, historian François Delaporte notes that yellow fever

research was a contentious issue. Scientists, including Finlay and

Reed, became successful by building on the work of less prominent

scientists, without always giving them the credit they were due. Reed's research was essential in the fight against yellow fever. He is also credited for using the first type of medical consent

form during his experiments in Cuba, an attempt to ensure that

participants knew they were taking a risk by being part of testing.

Like Cuba and Panama, Brazil also led a highly successful sanitation

campaign against mosquitoes and yellow fever. Beginning in 1903, the

campaign led by Oswaldo Cruz,

then director general of public health, resulted not only in

eradicating the disease but also in reshaping the physical landscape of

Brazilian cities such as Rio de Janeiro. During rainy seasons, Rio de

Janeiro had regularly suffered floods, as water from the bay surrounding

the city overflowed into Rio's narrow streets. Coupled with the poor

drainage systems found throughout Rio, this created swampy conditions in

the city's neighborhoods. Pools of stagnant water stood year-long in

city streets and proved to be a fertile ground for disease-carrying

mosquitoes. Thus, under Cruz's direction, public health units known as

"mosquito inspectors" fiercely worked to combat yellow fever throughout

Rio by spraying, exterminating rats, improving drainage, and destroying

unsanitary housing. Ultimately, the city's sanitation and renovation

campaigns reshaped Rio de Janeiro's neighborhoods. Its poor residents

were pushed from city centers to Rio's suburbs, or to towns found in the

outskirts of the city. In later years, Rio's most impoverished

inhabitants would come to reside in favelas.

During 1920–23, the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board undertook an expensive and successful yellow fever eradication campaign in Mexico.

The IHB gained the respect of Mexico's federal government because of

the success. The eradication of yellow fever strengthened the

relationship between the US and Mexico, which had not been very good in

the years prior. The eradication of yellow fever was also a major step

toward better global health.

In 1927, scientists isolated yellow fever virus in West Africa. Following this, two vaccines were developed in the 1930s. Vaccine 17D is still in use although newer vaccines, based on vero cells, are in development.

Current status

Using

vector control and strict vaccination programs, the urban cycle of

yellow fever was nearly eradicated from South America. Since 1943, only a

single urban outbreak in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, has occurred. Since the 1980s, however, the number of yellow fever cases has been increasing again, and A. aegypti

has returned to the urban centers of South America. This is partly due

to limitations on available insecticides, as well as habitat

dislocations caused by climate change. It is also because the vector

control program was abandoned. Although no new urban cycle has yet been

established, scientists believe this could happen again at any point. An

outbreak in Paraguay in 2008 was thought to be urban in nature, but this ultimately proved not to be the case.

In Africa, virus eradication programs have mostly relied upon

vaccination. These programs have largely been unsuccessful because they

were unable to break the sylvatic cycle involving wild primates. With

few countries establishing regular vaccination programs, measures to

fight yellow fever have been neglected, making the future spread of the

virus more likely.

Research

In the hamster model of yellow fever, early administration of the antiviral ribavirin is an effective treatment of many pathological features of the disease.

Ribavirin treatment during the first five days after virus infection

improved survival rates, reduced tissue damage in the liver and spleen, prevented hepatocellular steatosis,

and normalised levels of alanine aminotransferase, a liver damage

marker. The mechanism of action of ribavirin in reducing liver pathology

in yellow fever virus infection may be similar to its activity in treatment of hepatitis C, a related virus.

Because ribavirin had failed to improve survival in a virulent rhesus

model of yellow fever infection, it had been previously discounted as a

possible therapy. Infection was reduced in mosquitoes with the wMel strain of Wolbachia.

Yellow fever has been researched by several countries as a potential biological weapon.