The prebiotic atmosphere is the second atmosphere present on Earth before today's biotic, oxygen-rich third atmosphere, and after the first atmosphere (which was mainly water vapor and simple hydrides) of Earth's formation. The formation of the Earth, roughly 4.5 billion years ago, involved multiple collisions and coalescence of planetary embryos. This was followed by a <100 million year period on Earth where a magma ocean was present, the atmosphere was mainly steam, and surface temperatures reached up to 8,000 K (14,000 °F). Earth's surface then cooled and the atmosphere stabilized, establishing the prebiotic atmosphere. The environmental conditions during this time period were quite different from today: the Sun was ~30% dimmer overall yet brighter at ultraviolet and x-ray wavelengths, there was a liquid ocean, it is unknown if there were continents but oceanic islands were likely, Earth's interior chemistry (and thus, volcanic activity) was different, and there was a larger flux of impactors (e.g. comets and asteroids) hitting Earth's surface.

Studies have attempted to constrain the composition and nature of the prebiotic atmosphere by analyzing geochemical data and using theoretical models that include our knowledge of the early Earth environment. These studies indicate that the prebiotic atmosphere likely contained more CO2 than the modern Earth, had N2 within a factor of 2 of the modern levels, and had vanishingly low amounts of O2. The atmospheric chemistry is believed to have been "weakly reducing", where reduced gases like CH4, NH3, and H2 were present in small quantities. The composition of the prebiotic atmosphere was likely periodically altered by impactors, which may have temporarily caused the atmosphere to have been "strongly reduced".

Constraining the composition of the prebiotic atmosphere is key to understanding the origin of life, as it may facilitate or inhibit certain chemical reactions on Earth's surface believed to be important for the formation of the first living organism. Life on Earth originated and began modifying the atmosphere at least 3.5 billion years ago and possibly much earlier, which marks the end of the prebiotic atmosphere.

Environmental context

Establishment of the prebiotic atmosphere

Earth is believed to have formed over 4.5 billion years ago by accreting material from the solar nebula. Earth's Moon formed in a collision, the Moon-forming impact, believed to have occurred 30-50 million years after the Earth formed. In this collision, a Mars-sized object named Theia collided with the primitive Earth and the remnants of the collision formed the Moon. The collision likely supplied enough energy to melt most of Earth's mantle and vaporize roughly 20% of it, heating Earth's surface to as high as 8,000 K (~14,000 °F). Earth's surface in the aftermath of the Moon-forming impact was characterized by high temperatures (~2,500 K), an atmosphere made of rock vapor and steam, and a magma ocean. As the Earth cooled by radiating away the excess energy from the impact, the magma ocean solidified and volatiles were partitioned between the mantle and atmosphere until a stable state was reached. It is estimated that Earth transitioned from the hot, post-impact environment into a potentially habitable environment with crustal recycling, albeit different from modern plate tectonics, roughy 10-20 million years after the Moon-forming impact, around 4.4 billion years ago. The atmosphere present from this point in Earth's history until the origin of life is referred to as the prebiotic atmosphere.

It is unknown when exactly life originated. The oldest direct evidence for life on Earth is around 3.5 billion years old, such as fossil stromatolites from North Pole, Western Australia. Putative evidence of life on Earth from older times (e.g. 3.8 and 4.1 billion years ago) lacks additional context necessary to claim it is truly of biotic origin, so it is still debated. Thus, the prebiotic atmosphere concluded 3.5 billion years ago or earlier, placing it in the early Archean Eon or mid-to-late Hadean Eon.

Environmental factors

Knowledge of the environmental factors at play on early Earth is required to investigate the prebiotic atmosphere. Much of what we know about the prebiotic environment comes from zircons - crystals of zirconium silicate (ZrSiO4). Zircons are useful because they record the physical and chemical processes occurring on the prebiotic Earth during their formation and they are especially durable. Most zircons that are dated to the prebiotic time period are found at the Jack Hills formation of Western Australia, but they also occur elsewhere. Geochemical data from several prebiotic zircons show isotopic evidence for chemical change induced by liquid water, indicating that the prebiotic environment had a liquid ocean and a surface temperature that did not cause it to freeze or boil. It is unknown when exactly the continents emerged above this liquid ocean. This adds uncertainty to the interaction between Earth's prebiotic surface and atmosphere, as the presence of exposed land determines the rate of weathering processes and provides local environments that may be necessary for life to form. However, oceanic islands were likely. Additionally, the oxidation state of Earth's mantle was likely different at early times, which changes the fluxes of chemical species delivered to the atmosphere from volcanic outgassing.

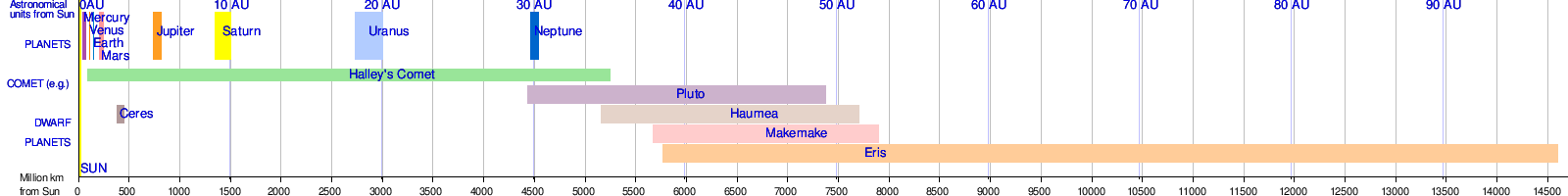

Environmental factors from elsewhere in the solar system also affected prebiotic Earth. The Sun was ~30% dimmer overall around the time the Earth formed. This means greenhouse gases may have been required in higher levels than present day to keep Earth from freezing over. Despite the overall reduction in energy coming from the Sun, the early Sun emitted more radiation in the ultraviolet and x-ray regimes than it currently does. This indicates that different photochemical reactions may have dominated early Earth's atmosphere, which has implications for global atmospheric chemistry and the formation of important compounds that could lead to the origin of life. Finally, there was a significantly higher flux of objects that impacted Earth - such as comets and asteroids - in the early solar system. These impactors may have been important in the prebiotic atmosphere because they can deliver material to the atmosphere, eject material from the atmosphere, and change the chemical nature of the atmosphere after their arrival.

Atmospheric composition

The exact composition of the prebiotic atmosphere is unknown due to the lack of geochemical data from the time period. Current studies generally indicate that the prebiotic atmosphere was "weakly reduced", with elevated levels of CO2, N2 within a factor of 2 of the modern level, negligible amounts of O2, and more hydrogen-bearing gases than the modern Earth (see below). Noble gases and photochemical products of the dominant species were also present in small quantities.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an important component of the prebiotic atmosphere because, as a greenhouse gas, it strongly affects the surface temperature; also, it dissolves in water and can change the ocean pH. The abundance of carbon dioxide in the prebiotic atmosphere is not directly constrained by geochemical data and must be inferred.

Evidence suggests that the carbonate-silicate cycle regulates Earth's atmospheric carbon dioxide abundance on timescales of about 1 million years. The carbonate-silicate cycle is a negative feedback loop that modulates Earth's surface temperature by partitioning carbon between the atmosphere and the mantle via several surface processes. It has been proposed that the processes of the carbonate-silicate cycle would result in high CO2 levels in the prebiotic atmosphere to offset the lower energy input from the faint young Sun. This mechanism can be used to estimate the prebiotic CO2 abundance, but it is debated and uncertain. Uncertainty is primarily driven by a lack of knowledge about the area of exposed land, early Earth's interior chemistry and structure, the rate of reverse weathering and seafloor weathering, and the increased impactor flux. One extensive modeling study suggests that CO2 was roughly 20 times higher in the prebiotic atmosphere than the preindustrial modern value (280 ppm), which would result in a global average surface temperature around 259 K (6.5 °F) and an ocean pH around 7.9. This is in agreement with other studies, which generally conclude that the prebiotic atmospheric CO2 abundance was higher than the modern one, although the global surface temperature may still be significantly colder due to the faint young Sun.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen in the form of N2 is 78% of Earth's modern atmosphere by volume, making it the most abundant gas. N2 is generally considered a background gas in the Earth's atmosphere because it is relatively unreactive due to the strength of its triple bond. Despite this, atmospheric N2 was at least moderately important to the prebiotic environment because it impacts the climate via Rayleigh scattering and it may have been more photochemically active under the enhanced x-ray and ultraviolet radiation from the young Sun. N2 was also likely important for the synthesis of compounds believed to be critical for the origin of life, such as hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and amino acids derived from HCN. Studies have attempted to constrain the prebiotic atmosphere N2 abundance with theoretical estimates, models, and geologic data. These studies have resulted in a range of possible constraints on the prebiotic N2 abundance. For example, a recent modeling study that incorporates atmospheric escape, magma ocean chemistry, and the evolution of Earth's interior chemistry suggests that the atmospheric N2 abundance was probably less than half of the present day value. However, this study fits into a larger body of work that generally constrains the prebiotic N2 abundance to be between half and double the present level.

Oxygen

Oxygen in the form of O2 makes up 21% of Earth's modern atmosphere by volume. Earth's modern atmospheric O2 is due almost entirely to biology (e.g. it is produced during oxygenic photosynthesis), so it was not nearly as abundant in the prebiotic atmosphere. This is favorable for the origin of life, as O2 would oxidize organic compounds needed in the origin of life. The prebiotic atmosphere O2 abundance can be theoretically calculated with models of atmospheric chemistry. The primary source of O2 in these models is the breakdown and subsequent chemical reactions of other oxygen containing compounds. Incoming solar photons or lightning can break up CO2 and H2O molecules, freeing oxygen atoms and other radicals (i.e. highly reactive gases in the atmosphere). The free oxygen can then combine into O2 molecules via several chemical pathways. The rate at which O2 is created in this process is determined by the incoming solar flux, the rate of lightning, and the abundances of the other atmospheric gases that take part in the chemical reactions (e.g. CO2, H2O, OH), as well as their vertical distributions. O2 is removed from the atmosphere via photochemical reactions that mainly involve H2 and CO near the surface. The most important of these reactions starts when H2 is split into two H atoms by incoming solar photons. The free H then reacts with O2 and eventually forms H2O, resulting in a net removal of O2 and a net increase in H2O. Models that simulate all of these chemical reactions in a potential prebiotic atmosphere show that an extremely small atmospheric O2 abundance is likely. In one such model that assumed values for CO2 and H2 abundances and sources, the O2 volume mixing ratio is calculated to be between 10−18 and 10−11 near the surface and up to 10−4 in the upper atmosphere.

Hydrogen and reduced gases

The hydrogen abundance in the prebiotic atmosphere can be viewed from the perspective of reduction-oxidation (redox) chemistry. The modern atmosphere is oxidizing, due to the large volume of atmospheric O2. In an oxidizing atmosphere, the majority of atoms that form atmospheric compounds (e.g. C) will be in an oxidized form (e.g. CO2) instead of a reduced form (e.g. CH4). In a reducing atmosphere, more species will be in their reduced, generally hydrogen-bearing forms. Because there was very little O2 in the prebiotic atmosphere, it is generally believed that the prebiotic atmosphere was "weakly reduced" - although some argue that the atmosphere was "strongly reduced". In a weakly reduced atmosphere, reduced gases (e.g. CH4 and NH3) and oxidized gases (e.g CO2) are both present. The actual H2 abundance in the prebiotic atmosphere has been estimated by doing a calculation that takes into account the rate at which H2 is volcanically outgassed to the surface and the rate at which it escapes to space. One of these recent calculations indicates that the prebiotic atmosphere H2 abundance was around 400 parts per million, but could have been significantly higher if the source from volcanic outgassing was enhanced or atmospheric escape was less efficient than expected. The abundances of other reduced species in the atmosphere can then be calculated with models of atmospheric chemistry.

Post-impact atmospheres

It has been proposed that the large flux of impactors in the early solar system may have significantly changed the nature of the prebiotic atmosphere. During the time period of the prebiotic atmosphere, it is expected that a few asteroid impacts large enough to vaporize the oceans and melt Earth's surface could have occurred, with smaller impacts expected in even larger numbers. These impacts would have significantly changed the chemistry of the prebiotic atmosphere by heating it up, ejecting some of it to space, and delivering new chemical material. Studies of post-impact atmospheres indicate that they would have caused the prebiotic atmosphere to be strongly reduced for a period of time after a large impact. On average, impactors in the early solar system contained highly reduced minerals (e.g. metallic iron) and were enriched with reduced compounds that readily enter the atmosphere as a gas. In these strongly reduced post-impact atmospheres, there would be significantly higher abundances of reduced gases like CH4, HCN, and perhaps NH3. Reduced, post-impact atmospheres after the ocean condensed are predicted to last up to tens of millions of years before returning to the background state.