| Myasthenia gravis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eye deviation and a drooping eyelid in a person with myasthenia gravis trying to open her eyes | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Varying degrees muscle weakness, double vision, drooping eyelids, trouble talking, trouble walking |

| Usual onset | Women under 40, men over 60 |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Autoimmune disease |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests for specific antibodies, edrophonium test, nerve conduction studies |

| Differential diagnosis | Guillain-Barre syndrome, botulism, organophosphate poisoning, brainstem stroke |

| Treatment | Medications, surgical removal of the thymus, plasmapheresis |

| Medication | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (neostigmine, pyridostigmine), immunosuppressants |

| Frequency | 50 to 200 per million |

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a long-term neuromuscular disease that leads to varying degrees of skeletal muscle weakness. The most commonly affected muscles are those of the eyes, face, and swallowing. It can result in double vision, drooping eyelids, trouble talking, and trouble walking. Onset can be sudden. Those affected often have a large thymus or develop a thymoma.

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease which results from antibodies that block or destroy nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at the junction between the nerve and muscle. This prevents nerve impulses from triggering muscle contractions. Rarely, an inherited genetic defect in the neuromuscular junction results in a similar condition known as congenital myasthenia. Babies of mothers with myasthenia may have symptoms during their first few months of life, known as neonatal myasthenia. Diagnosis can be supported by blood tests for specific antibodies, the edrophonium test, or a nerve conduction study.

Myasthenia gravis is generally treated with medications known as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine and pyridostigmine. Immunosuppressants, such as prednisone or azathioprine, may also be used. The surgical removal of the thymus may improve symptoms in certain cases. Plasmapheresis and high dose intravenous immunoglobulin may be used during sudden flares of the condition. If the breathing muscles become significantly weak, mechanical ventilation may be required.

MG affects 50 to 200 per million people. It is newly diagnosed in three to 30 per million people each year. Diagnosis is becoming more common due to increased awareness. It most commonly occurs in women under the age of 40 and in men over the age of 60. It is uncommon in children. With treatment, most of those affected lead relatively normal lives and have a normal life expectancy. The word is from the Greek mys "muscle" and astheneia "weakness", and the Latin: gravis "serious".

Signs and symptoms

The initial, main symptom in MG is painless weakness of specific muscles, not fatigue.

The muscle weakness becomes progressively worse during periods of

physical activity and improves after periods of rest. Typically, the

weakness and fatigue are worse toward the end of the day.

MG generally starts with ocular (eye) weakness; it might then progress

to a more severe generalized form, characterized by weakness in the

extremities or in muscles that govern basic life functions.

Eyes

In about two-thirds of individuals, the initial symptom of MG is related to the muscles around the eye. There may be eyelid drooping (ptosis due to weakness of levator palpebrae superioris) and double vision (diplopia, due to weakness of the extraocular muscles). Eye symptoms tend to get worse when watching television, reading, or driving, particularly in bright conditions. Consequently, some affected individuals choose to wear sunglasses.

The term "ocular myasthenia gravis" describes a subtype of MG where

muscle weakness is confined to the eyes, i.e. extraocular muscles,

levator palpebrae superioris, and orbicularis oculi. Typically, this subtype evolves into generalized MG, usually after a few years.

Eating

The weakness of the muscles involved in swallowing may lead to swallowing difficulty (dysphagia). Typically, this means that some food may be left in the mouth after an attempt to swallow, or food and liquids may regurgitate into the nose rather than go down the throat (velopharyngeal insufficiency). Weakness of the muscles that move the jaw (muscles of mastication) may cause difficulty chewing. In individuals with MG, chewing tends to become more tiring when chewing tough, fibrous foods. Difficulty in swallowing, chewing, and speaking is the first symptom in about one-sixth of individuals.

Speaking

Weakness of the muscles involved in speaking may lead to dysarthria and hypophonia. Speech may be slow and slurred, or have a nasal quality. In some cases, a singing hobby or profession must be abandoned.

Head and neck

Due to weakness of the muscles of facial expression and muscles of mastication, facial weakness may manifest as the inability to hold the mouth closed (the "hanging jaw sign") and as a snarling expression when attempting to smile. With drooping eyelids, facial weakness may make the individual appear sleepy or sad. Difficulty in holding the head upright may occur.

Other

The muscles that control breathing (dyspnea)

and limb movements can also be affected; rarely do these present as the

first symptoms of MG, but develop over months to years. In a myasthenic crisis, a paralysis of the respiratory muscles occurs, necessitating assisted ventilation to sustain life.

Crises may be triggered by various biological stressors such as

infection, fever, an adverse reaction to medication, or emotional

stress.

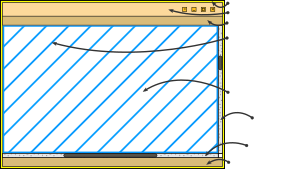

Pathophysiology

Neuromuscular junction: 1. Axon 2. Muscle cell membrane 3. Synaptic vesicle 4. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor 5. Mitochondrion

A juvenile thymus shrinks with age.

MG is an autoimmune synaptopathy.

The disorder occurs when the immune system malfunctions and generates

antibodies that attack the body's tissues. The antibodies in MG attack a

normal human protein, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, or a

related protein called MuSK a muscle-specific kinase. Other less frequent antibodies are found against LRP4, Agrin and titin proteins.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes are associated with

increased susceptibility to myasthenia gravis and other autoimmune

disorders. Relatives of MG patients have a higher percentage of other

immune disorders.

The thymus gland cells form part of the body's immune system. In

those with myasthenia gravis, the thymus gland is large and abnormal. It

sometimes contains clusters of immune cells which indicate lymphoid

hyperplasia, and the thymus gland may give wrong instructions to immune

cells.

In pregnancy

For

women who are pregnant and already have MG, in a third of cases, they

have been known to experience an exacerbation of their symptoms, and in

those cases it usually occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy. Signs and symptoms in pregnant mothers tend to improve during the second and third trimesters. Complete remission can occur in some mothers. Immunosuppressive therapy

should be maintained throughout pregnancy, as this reduces the chance

of neonatal muscle weakness, and controls the mother's myasthenia.

About 10–20% of infants with mothers affected by the condition are born with transient neonatal myasthenia (TNM), which generally produces feeding and respiratory difficulties that develop about 12 hours to several days after birth. A child with TNM typically responds very well to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors,

and the condition generally resolves over a period of three weeks as

the antibodies diminish and generally does not result in any

complications. Very rarely, an infant can be born with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, secondary to profound intrauterine weakness. This is due to maternal antibodies that target an infant's acetylcholine receptors. In some cases, the mother remains asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

MG

can be difficult to diagnose, as the symptoms can be subtle and hard to

distinguish from both normal variants and other neurological disorders.

Three types of myasthenic symptoms in children can be distinguished:

- Transient neonatal myasthenia occurs in 10 to 15% of babies born to mothers afflicted with the disorder, and disappears after a few weeks.

- Congenitalmyasthenia, the rarest form, occurs when genes are present from both parents.

- Juvenile myasthenia gravis is most common in females.

Congenital myasthenias cause muscle weakness and fatigability similar to those of MG.

The signs of congenital myasthenia usually are present in the first

years of childhood, although they may not be recognized until adulthood.

Classification

When

diagnosed with MG, a person is assessed for his or her neurological

status and the level of illness is established. This is usually done

using the accepted Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical

Classification scale, which is:

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Any eye muscle weakness, possible ptosis, no other evidence of muscle weakness elsewhere |

| II | Eye muscle weakness of any severity, mild weakness of other muscles |

| IIa | Predominantly limb or axial muscles |

| IIb | Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles |

| III | Eye muscle weakness of any severity, moderate weakness of other muscles |

| IIIa | Predominantly limb or axial muscles |

| IIIb | Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles |

| IV | Eye muscle weakness of any severity, severe weakness of other muscles |

| IVa | Predominantly limb or axial muscles |

| IVb | Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles |

| V | Intubation needed to maintain airway |

Physical examination

During

a physical examination to check for MG, a doctor might ask the person

to perform repetitive movements. For instance, the doctor may ask one to

look at a fixed point for 30 seconds and to relax the muscles of the

forehead. This is done because a person with MG and ptosis of the eyes

might be involuntarily using the forehead muscles to compensate for the

weakness in the eyelids.

The clinical examiner might also try to elicit the "curtain sign" in a

patient by holding one of the person's eyes open, which in the case of

MG will lead the other eye to close.

Blood tests

If the diagnosis is suspected, serology can be performed:

- One test is for antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor; the test has a reasonable sensitivity of 80–96%, but in ocular myasthenia, the sensitivity falls to 50%.

- A proportion of the patients without antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor have antibodies against the MuSK protein.

- In specific situations, testing is performed for Lambert-Eaton syndrome.

Electrodiagnostics

A chest CT-scan showing a thymoma (red circle)

Photograph

of a patient showing right partial ptosis (left picture), the left lid

shows compensatory pseudo lid retraction because of equal innervation of

the levator palpabrae superioris (Hering's law of equal innervation): Right picture: after an edrophonium test, note the improvement in ptosis.

Muscle fibers of people with MG are easily fatigued, which the repetitive nerve stimulation test can help diagnose. In single-fiber electromyography, which is considered to be the most sensitive (although not the most specific) test for MG,

a thin needle electrode is inserted into different areas of a

particular muscle to record the action potentials from several samplings

of different individual muscle fibers. Two muscle fibers belonging to

the same motor unit are identified, and the temporal variability in

their firing patterns is measured. Frequency and proportion of

particular abnormal action potential patterns, called "jitter" and

"blocking", are diagnostic. Jitter refers to the abnormal variation in

the time interval between action potentials of adjacent muscle fibers in

the same motor unit. Blocking refers to the failure of nerve impulses

to elicit action potentials in adjacent muscle fibers of the same motor

unit.

Ice test

Applying

ice for two to five minutes to the muscles reportedly has a sensitivity

and specificity of 76.9% and 98.3%, respectively, for the

identification of MG. Acetylcholinesterase is thought to be inhibited at

the lower temperature, and this is the basis for this diagnostic test.

This generally is performed on the eyelids when a ptosis is present, and

is deemed positive if a ≥2 mm rise in the eyelid occurs after the ice

is removed.

Edrophonium test

This test requires the intravenous administration of edrophonium chloride or neostigmine, drugs that block the breakdown of acetylcholine by cholinesterase (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors). This test is no longer typically performed, as its use can lead to life-threatening bradycardia (slow heart rate) which requires immediate emergency attention. Production of edrophonium was discontinued in 2008.

Imaging

A chest X-ray may identify widening of the mediastinum suggestive of thymoma, but computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more sensitive ways to identify thymomas and are generally done for this reason.

MRI of the cranium and orbits may also be performed to exclude

compressive and inflammatory lesions of the cranial nerves and ocular

muscles.

Pulmonary function test

The forced vital capacity may be monitored at intervals to detect increasing muscular weakness. Acutely, negative inspiratory force may be used to determine adequacy of ventilation; it is performed on those individuals with MG.

Management

Treatment is by medication and/or surgery. Medication consists mainly of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors to directly improve muscle function and immunosuppressant drugs to reduce the autoimmune process. Thymectomy is a surgical method to treat MG.

Medication

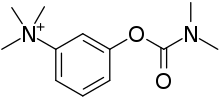

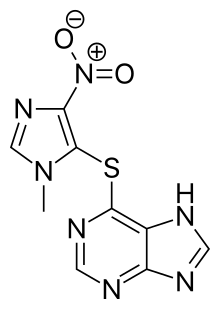

Neostigmine, chemical structure

Azathioprine, chemical structure

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can provide symptomatic benefit and may not fully remove a person's weakness from MG.

While they might not fully remove all symptoms of MG, they still may

allow a person the ability to perform normal daily activities.

Usually, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are started at a low dose and

increased until the desired result is achieved. If taken 30 minutes

before a meal, symptoms will be mild during eating, which is helpful for

those who have difficulty swallowing due to their illness. Another

medication used for MG, atropine, can reduce the muscarinic side effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Pyridostigmine

is a relatively long-acting drug (when compared to other cholinergic

agonists), with a half-life around four hours with relatively few side

effects.

Generally, it is discontinued in those who are being mechanically

ventilated as it is known to increase the amount of salivary secretions.

A few high-quality studies have directly compared cholinesterase

inhibitors with other treatments (or placebo); their practical benefit

may be such that it would be difficult to conduct studies in which they

would be withheld from some people. The steroid prednisone

might also be used to achieve a better result, but it can lead to the

worsening of symptoms for 14 days and takes 6–8 weeks to achieve its

maximal effectiveness. Due to the myriad symptoms that steroid treatments can cause, it is not the preferred method of treatment. Other immune suppressing medications may also be used including rituximab. About 10% of people with generalized MG are considered treatment-refractory.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

(HSCT) is sometimes used in severe, treatment-refractory MG. Available

data provide preliminary evidence that HSCT can be an effective

therapeutic option in carefully selected cases.

Plasmapheresis and IVIG

If the myasthenia is serious (myasthenic crisis), plasmapheresis can be used to remove the putative antibodies from the circulation. Also, intravenous immunoglobulins

(IVIGs) can be used to bind the circulating antibodies. Both of these

treatments have relatively short-lived benefits, typically measured in

weeks, and often are associated with high costs which make them

prohibitive; they are generally reserved for when MG requires

hospitalization.

Surgery

As thymomas

are seen in 10% of all people with the MG, people are often given a

chest X-ray and CT scan to evaluate their need for surgical removal of

their thymus and any cancerous tissue that may be present. Even if surgery is performed to remove a thymoma, it generally does not lead to the remission of MG.

Surgery in the case of MG involves the removal of the thymus, although

in 2013 there was no clear indication of any benefit except in the

presence of a thymoma. A 2016 randomized controlled trial, however, found some benefits.

Physical measures

Patients

with MG should be educated regarding the fluctuating nature of their

symptoms, including weakness and exercise-induced fatigue. Exercise

participation should be encouraged with frequent rest. In people with generalized MG, some evidence indicates a partial home program including training in diaphragmatic breathing, pursed lip breathing,

and interval-based muscle therapy may improve respiratory muscle

strength, chest wall mobility, respiratory pattern, and respiratory

endurance.

Medical imaging

In people with myasthenia gravis, older forms of iodinated contrast

used for medical imaging have caused an increased risk of exacerbation

of the disease, but modern forms have no immediate increased risk.

Prognosis

The prognosis of MG patients is generally good, as is quality of life, given very good treatment.

In the early 1900s, the mortality associated with MG was 70%; now, that

number is estimated to be around 3–5%, which is attributed to increased

awareness and medications to manage symptoms.

Monitoring of a person with MG is very important, as at least 20% of

people diagnosed with it will experience a myasthenic crisis within two

years of their diagnosis, requiring rapid medical intervention. Generally, the most disabling period of MG might be years after the initial diagnosis.

Epidemiology

Myasthenia

gravis occurs in all ethnic groups and both sexes. It most commonly

affects women under 40 and people from 50 to 70 years old of either sex,

but it has been known to occur at any age. Younger patients rarely have

thymoma. The prevalence in the United States is estimated at between 0.5 and 20.4 cases per 100,000, with an estimated 60,000 Americans affected. Within the United Kingdom, an estimated 15 cases of MG occur per 100,000 people.

History

The first to write about MG were Thomas Willis, Samuel Wilks, Erb, and Goldflam. The term "myasthenia gravis pseudo-paralytica" was proposed in 1895 by Jolly, a German physician. Mary Walker treated a person with MG with physostigmine in 1934. Simpson and Nastuck detailed the autoimmune nature of the condition.[12]

In 1973, Patrick and Lindstrom used rabbits to show that immunization

with purified muscle-like acetylcholine receptors caused the development

of MG-like symptoms.

Research

Immunomodulating

substances, such as drugs that prevent acetylcholine receptor

modulation by the immune system, are currently being researched. Some research recently has been on anti-c5 inhibitors for treatment research as they are safe and used in the treatment of other diseases. Ephedrine seems to benefit some people more than other medications, but it has not been properly studied as of 2014.

In the laboratory MG is mostly studied in model organisms, such as

rodents. In addition, in 2015, scientists developed an in vitro

functional all-human, neuromuscular junction assay from human embryonic stem cells

and somatic-muscle stem cells. After the addition of pathogenic

antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor and activation of the complement system, the neuromuscular co-culture shows symptoms such as weaker muscle contractions.