A cryptocurrency, crypto-currency, or crypto is a collection of binary data which is designed to work as a medium of exchange wherein individual coin ownership records are stored in a ledger which is a computerized database using strong cryptography to secure transaction records, to control the creation of additional coins, and to verify the transfer of coin ownership. Some crypto schemes use validators to maintain the cryptocurrency. In a proof-of-stake model, owners put up their tokens as collateral. In return, they get authority over the token in proportion to the amount they stake. Generally, these token stakers get additional ownership in the token over time via network fees, newly minted tokens or other such reward mechanisms. Cryptocurrency does not exist in physical form (like paper money) and is typically not issued by a central authority. Cryptocurrencies typically use decentralized control as opposed to a central bank digital currency (CBDC). When a cryptocurrency is minted or created prior to issuance or issued by a single issuer, it is generally considered centralized. When implemented with decentralized control, each cryptocurrency works through distributed ledger technology, typically a blockchain, that serves as a public financial transaction database.

Bitcoin, first released as open-source software in 2009, is the first decentralized cryptocurrency. Since the release of bitcoin, many other cryptocurrencies have been created.

History

In 1983, the American cryptographer David Chaum conceived an anonymous cryptographic electronic money called ecash. Later, in 1995, he implemented it through Digicash, an early form of cryptographic electronic payments which required user software in order to withdraw notes from a bank and designate specific encrypted keys before it can be sent to a recipient. This allowed the digital currency to be untraceable by the issuing bank, the government, or any third party.

In 1996, the National Security Agency published a paper entitled How to Make a Mint: the Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash, describing a Cryptocurrency system, first publishing it in an MIT mailing list and later in 1997, in The American Law Review (Vol. 46, Issue 4).

In 1998, Wei Dai published a description of "b-money", characterized as an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system. Shortly thereafter, Nick Szabo described bit gold. Like bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies that would follow it, bit gold (not to be confused with the later gold-based exchange, BitGold) was described as an electronic currency system which required users to complete a proof of work function with solutions being cryptographically put together and published.

In 2009, the first decentralized cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was created by presumably pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. It used SHA-256, a cryptographic hash function, in its proof-of-work scheme. In April 2011, Namecoin was created as an attempt at forming a decentralized DNS, which would make internet censorship very difficult. Soon after, in October 2011, Litecoin was released. It used scrypt as its hash function instead of SHA-256. Another notable cryptocurrency, Peercoin, used a proof-of-work/proof-of-stake hybrid.

On 6 August 2014, the UK announced its Treasury had commissioned a study of cryptocurrencies, and what role, if any, they could play in the UK economy. The study was also to report on whether regulation should be considered. Its final report was published in 2018, and it issued a consultation on cryptoassets and stablecoins in January 2021.

In June 2021, El Salvador became the first country to accept Bitcoin as legal tender, after the Legislative Assembly had voted 62–22 to pass a bill submitted by President Nayib Bukele classifying the cryptocurrency as such.

In August 2021, Cuba followed with Resolution 215 to accept Bitcoin as legal tender, which will circumvent U.S. sanctions.

In September 2021, the government of China, the single largest market for cryptocurrency, declared all cryptocurrency transactions illegal, completing a crackdown on cryptocurrency that had previously banned the operation of intermediaries and miners within China.

Formal definition

According to Jan Lansky, a cryptocurrency is a system that meets six conditions:

- The system does not require a central authority; its state is maintained through distributed consensus.

- The system keeps an overview of cryptocurrency units and their ownership.

- The system defines whether new cryptocurrency units can be created. If new cryptocurrency units can be created, the system defines the circumstances of their origin and how to determine the ownership of these new units.

- Ownership of cryptocurrency units can be proved exclusively cryptographically.

- The system allows transactions to be performed in which ownership of the cryptographic units is changed. A transaction statement can only be issued by an entity proving the current ownership of these units.

- If two different instructions for changing the ownership of the same cryptographic units are simultaneously entered, the system performs at most one of them.

In March 2018, the word cryptocurrency was added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Altcoins

Tokens, cryptocurrencies, and other types of digital assets that are not bitcoin are collectively known as alternative cryptocurrencies, typically shortened to "altcoins" or "alt coins". Paul Vigna of The Wall Street Journal also described altcoins as "alternative versions of bitcoin" given its role as the model protocol for altcoin designers. The term is commonly used to describe coins and tokens created after bitcoin. A list of some cryptocurrencies can be found in the List of cryptocurrencies article.

Altcoins often have underlying differences with bitcoin. For example, Litecoin aims to process a block every 2.5 minutes, rather than bitcoin's 10 minutes, which allows Litecoin to confirm transactions faster than bitcoin. Another example is Ethereum, which has smart contract functionality that allows decentralized applications to be run on its blockchain. Ethereum was the most used blockchain in 2020, according to Bloomberg News. In 2016, it had the largest "following" of any altcoin, according to the New York Times.

Significant rallies across altcoin markets are often referred to as an "altseason".

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are altcoins that are designed to maintain a stable level of purchasing power. There are four primary types of stablecoins: fiat-backed stablecoins, cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins, algorithmic stablecoins, and commodity-backed stablecoins. Fiat-backed stablecoins like USD Coin maintain their price stability by being reserved with cash and US treasuries. Cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins like DAI are reserved by digital assets like Ethereum, typically in an overcollateralized manner so if the price of ETH drops below the loan-to-value ratio, the collateral is liquidated to maintain DAI's peg to the US Dollar. Algorithmic stablecoins, or Seigniorage-style stablecoins, use economic mechanisms to maintain price stability without requiring fiat or cryptocurrency collateralization.

Crypto token

A blockchain account can provide functions other than making payments, for example in decentralized applications or smart contracts. (Units of) fungible tokens are sometimes referred to as crypto tokens (or cryptotokens). These terms are usually reserved for other fungible tokens than the main cryptocurrency of the blockchain, that is, usually, for fungible tokens issued within a smart contract running on top of a blockchain such as Ethereum. There are also non-fungible tokens.

Architecture

Decentralized cryptocurrency is produced by the entire cryptocurrency system collectively, at a rate which is defined when the system is created and which is publicly known. In centralized banking and economic systems such as the Federal Reserve System, corporate boards or governments control the supply of currency by printing units of fiat money or demanding additions to digital banking ledgers. In the case of decentralized cryptocurrency, companies or governments cannot produce new units, and have not so far provided backing for other firms, banks or corporate entities which hold asset value measured in it. The underlying technical system upon which decentralized cryptocurrencies are based was created by the group or individual known as Satoshi Nakamoto.

As of May 2018, over 1,800 cryptocurrency specifications existed. Within a proof-of-work cryptocurrency system such as Bitcoin, the safety, integrity and balance of ledgers is maintained by a community of mutually distrustful parties referred to as miners: who use their computers to help validate and timestamp transactions, adding them to the ledger in accordance with a particular timestamping scheme. In a proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchain, transactions are validated by holders of the associated cryptocurrency, sometimes grouped together in stake pools.

Most cryptocurrencies are designed to gradually decrease the production of that currency, placing a cap on the total amount of that currency that will ever be in circulation. Compared with ordinary currencies held by financial institutions or kept as cash on hand, cryptocurrencies can be more difficult for seizure by law enforcement.

Blockchain

The validity of each cryptocurrency's coins is provided by a blockchain. A blockchain is a continuously growing list of records, called blocks, which are linked and secured using cryptography. Each block typically contains a hash pointer as a link to a previous block, a timestamp and transaction data. By design, blockchains are inherently resistant to modification of the data. It is "an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way". For use as a distributed ledger, a blockchain is typically managed by a peer-to-peer network collectively adhering to a protocol for validating new blocks. Once recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered retroactively without the alteration of all subsequent blocks, which requires collusion of the network majority.

Blockchains are secure by design and are an example of a distributed computing system with high Byzantine fault tolerance. Decentralized consensus has therefore been achieved with a blockchain.

Nodes

In the world of Cryptocurrency, a node is a computer that connects to a cryptocurrency network. The node supports the relevant cryptocurrency's network through either; relaying transactions, validation or hosting a copy of the blockchain. In terms of relaying transactions each network computer (node) has a copy of the blockchain of the cryptocurrency it supports, when a transaction is made the node creating the transaction broadcasts details of the transaction using encryption to other nodes throughout the node network so that the transaction (and every other transaction) is known.

Node owners are either volunteers, those hosted by the organisation or body responsible for developing the cryptocurrency blockchain network technology or those that are enticed to host a node to receive rewards from hosting the node network.

Timestamping

Cryptocurrencies use various timestamping schemes to "prove" the validity of transactions added to the blockchain ledger without the need for a trusted third party.

The first timestamping scheme invented was the proof-of-work scheme. The most widely used proof-of-work schemes are based on SHA-256 and scrypt.

Some other hashing algorithms that are used for proof-of-work include CryptoNight, Blake, SHA-3, and X11.

The proof-of-stake is a method of securing a cryptocurrency network and achieving distributed consensus through requesting users to show ownership of a certain amount of currency. It is different from proof-of-work systems that run difficult hashing algorithms to validate electronic transactions. The scheme is largely dependent on the coin, and there's currently no standard form of it. Some cryptocurrencies use a combined proof-of-work and proof-of-stake scheme.

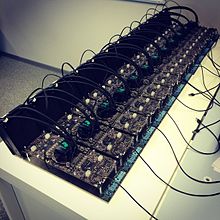

Mining

In cryptocurrency networks, mining is a validation of transactions. For this effort, successful miners obtain new cryptocurrency as a reward. The reward decreases transaction fees by creating a complementary incentive to contribute to the processing power of the network. The rate of generating hashes, which validate any transaction, has been increased by the use of specialized machines such as FPGAs and ASICs running complex hashing algorithms like SHA-256 and scrypt. This arms race for cheaper-yet-efficient machines has existed since the day the first cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was introduced in 2009. With more people venturing into the world of virtual currency, generating hashes for this validation has become far more complex over the years, with miners having to invest large sums of money on employing multiple high performance ASICs. Thus the value of the currency obtained for finding a hash often does not justify the amount of money spent on setting up the machines, the cooling facilities to overcome the heat they produce, and the electricity required to run them. Favorite regions for mining include those with cheap electricity, a cold climate, and jurisdictions with clear and conducive regulations. As of July 2019, bitcoin's electricity consumption is estimated to about 7 gigawatts, 0.2% of the global total, or equivalent to that of Switzerland.

Some miners pool resources, sharing their processing power over a network to split the reward equally, according to the amount of work they contributed to the probability of finding a block. A "share" is awarded to members of the mining pool who present a valid partial proof-of-work.

As of February 2018, the Chinese Government halted trading of virtual currency, banned initial coin offerings and shut down mining. Many Chinese miners have since relocated to Canada and Texas. One company is operating data centers for mining operations at Canadian oil and gas field sites, due to low gas prices. In June 2018, Hydro Quebec proposed to the provincial government to allocate 500 MW to crypto companies for mining. According to a February 2018 report from Fortune, Iceland has become a haven for cryptocurrency miners in part because of its cheap electricity.

In March 2018, the city of Plattsburgh in upstate New York put an 18-month moratorium on all cryptocurrency mining in an effort to preserve natural resources and the "character and direction" of the city.

GPU price rise

An increase in cryptocurrency mining increased the demand for graphics cards (GPU) in 2017. (The computing power of GPUs makes them well-suited to generating hashes.) Popular favorites of cryptocurrency miners such as Nvidia's GTX 1060 and GTX 1070 graphics cards, as well as AMD's RX 570 and RX 580 GPUs, doubled or tripled in price – or were out of stock. A GTX 1070 Ti which was released at a price of $450 sold for as much as $1100. Another popular card GTX 1060's 6 GB model was released at an MSRP of $250, sold for almost $500. RX 570 and RX 580 cards from AMD were out of stock for almost a year. Miners regularly buy up the entire stock of new GPU's as soon as they are available.

Nvidia has asked retailers to do what they can when it comes to selling GPUs to gamers instead of miners. "Gamers come first for Nvidia," said Boris Böhles, PR manager for Nvidia in the German region.

Wallets

A cryptocurrency wallet stores the public and private "keys" (address) or seed which can be used to receive or spend the cryptocurrency. With the private key, it is possible to write in the public ledger, effectively spending the associated cryptocurrency. With the public key, it is possible for others to send currency to the wallet.

There exist multiple methods of storing keys or seed in a wallet from using paper wallets which are traditional public, private or seed keys written on paper to using hardware wallets which are dedicated hardware to securely store your wallet information, using a digital wallet which is a computer with a software hosting your wallet information, hosting your wallet using an exchange where cryptocurrency is traded. or by storing your wallet information on a digital medium such as plaintext.

Anonymity

Bitcoin is pseudonymous rather than anonymous in that the cryptocurrency within a wallet is not tied to people, but rather to one or more specific keys (or "addresses"). Thereby, bitcoin owners are not identifiable, but all transactions are publicly available in the blockchain. Still, cryptocurrency exchanges are often required by law to collect the personal information of their users.

Additions such as Monero, Zerocoin, Zerocash and CryptoNote have been suggested, which would allow for additional anonymity and fungibility.

Economics

Cryptocurrencies are used primarily outside existing banking and governmental institutions and are exchanged over the Internet.

Block rewards

Proof-of-work cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, offer block rewards incentives for miners. There has been an implicit belief that whether miners are paid by block rewards or transaction fees does not affect the security of the blockchain, but a study suggests that this may not be the case under certain circumstances.

The rewards paid to miners increase the supply of the cryptocurrency. By making sure that verifying transactions is a costly business, the integrity of the network can be preserved as long as benevolent nodes control a majority of computing power. The verification algorithm requires a lot of processing power, and thus electricity in order to make verification costly enough to accurately validate public blockchain. Not only do miners have to factor in the costs associated with expensive equipment necessary to stand a chance of solving a hash problem, they further must consider the significant amount of electrical power in search of the solution. Generally, the block rewards outweigh electricity and equipment costs, but this may not always be the case.

The current value, not the long-term value, of the cryptocurrency supports the reward scheme to incentivize miners to engage in costly mining activities. Some sources claim that the current bitcoin design is very inefficient, generating a welfare loss of 1.4% relative to an efficient cash system. The main source for this inefficiency is the large mining cost, which is estimated to be US$360 Million per year. This translates into users being willing to accept a cash system with an inflation rate of 230% before being better off using bitcoin as a means of payment. However, the efficiency of the bitcoin system can be significantly improved by optimizing the rate of coin creation and minimizing transaction fees. Another potential improvement is to eliminate inefficient mining activities by changing the consensus protocol altogether.

Transaction fees

Transaction fees for cryptocurrency depend mainly on the supply of network capacity at the time, versus the demand from the currency holder for a faster transaction. The currency holder can choose a specific transaction fee, while network entities process transactions in order of highest offered fee to lowest. Cryptocurrency exchanges can simplify the process for currency holders by offering priority alternatives and thereby determine which fee will likely cause the transaction to be processed in the requested time.

For ether, transaction fees differ by computational complexity, bandwidth use, and storage needs, while bitcoin transaction fees differ by transaction size and whether the transaction uses SegWit. In September 2018, the median transaction fee for ether corresponded to $0.017, while for bitcoin it corresponded to $0.55.

Some cryptocurrencies have no transaction fees, and instead rely on client-side proof-of-work as the transaction prioritization and anti-spam mechanism.

Exchanges

Cryptocurrency exchanges allow customers to trade cryptocurrencies for other assets, such as conventional fiat money, or to trade between different digital currencies.

Atomic swaps

Atomic swaps are a mechanism where one cryptocurrency can be exchanged directly for another cryptocurrency, without the need for a trusted third party such as an exchange.

ATMs

Jordan Kelley, founder of Robocoin, launched the first bitcoin ATM in the United States on 20 February 2014. The kiosk installed in Austin, Texas, is similar to bank ATMs but has scanners to read government-issued identification such as a driver's license or a passport to confirm users' identities.

Initial coin offerings

An initial coin offering (ICO) is a controversial means of raising funds for a new cryptocurrency venture. An ICO may be used by startups with the intention of avoiding regulation. However, securities regulators in many jurisdictions, including in the U.S., and Canada, have indicated that if a coin or token is an "investment contract" (e.g., under the Howey test, i.e., an investment of money with a reasonable expectation of profit based significantly on the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others), it is a security and is subject to securities regulation. In an ICO campaign, a percentage of the cryptocurrency (usually in the form of "tokens") is sold to early backers of the project in exchange for legal tender or other cryptocurrencies, often bitcoin or ether.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, four of the 10 biggest proposed initial coin offerings have used Switzerland as a base, where they are frequently registered as non-profit foundations. The Swiss regulatory agency FINMA stated that it would take a "balanced approach" to ICO projects and would allow "legitimate innovators to navigate the regulatory landscape and so launch their projects in a way consistent with national laws protecting investors and the integrity of the financial system." In response to numerous requests by industry representatives, a legislative ICO working group began to issue legal guidelines in 2018, which are intended to remove uncertainty from cryptocurrency offerings and to establish sustainable business practices.

Trends

The "market cap" of any coin is calculated by multiplying the price by the number of coins in circulation. The total cryptocurrency market cap has historically been dominated by Bitcoin accounting for at least 50% of the market cap value where altcoins have increased and decreased in market cap value in relation to Bitcoin. Bitcoin's value is largely determined by speculation among other technological limiting factors known as block chain rewards coded into the architecture technology of Bitcoin itself. The cryptocurrency market cap follows a trend known as the "halving", which is when the block rewards received from Bitcoin are halved due to technological mandated limited factors instilled into Bitcoin which in turn limits the supply of Bitcoin. As the date reaches near of an halving (twice thus far historically) the cryptocurrency market cap increases, followed by a downtrend.

By mid-June 2021 cryptocurrency as an admittedly extremely volatile asset class for portfolio diversification had begun to be offered by some wealth managers in the US for 401(k)s.

Increased regulation in 2021

The rise in the popularity of cryptocurrencies and their adoption by financial institutions has led some governments to assess whether regulation is needed to protect users. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has defined cryptocurrency-related services as "virtual asset service providers" and recommended that they be regulated with the same money laundering (AML) and know your customer (KYC) requirements as financial institutions.

The European Commission published a digital finance strategy in September 2020. This included a draft regulation on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA), which aimed to provide a comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets in the EU.

On 10 June 2021, The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision proposed that banks that held cryptocurrency assets must set aside capital to cover all potential losses. For instance, if a bank were to hold bitcoin worth $2 billion, it would be required to set aside enough capital to cover the entire $2 billion. This is a more extreme standard than banks are usually held to when it comes to other assets. However, this is a proposal and not a regulation.

United States

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is considering what steps to take. On July 8, 2021, Senator Elizabeth Warren, who is part of the Senate Banking Committee, wrote to the chairman of the SEC and demanded that it provided answers on cryptocurrency regulation by July 28, 2021 due to the increase in cryptocurrency exchange use and the danger this poses to consumers.

China

On 18 May 2021, China banned financial institutions and payment companies from being able to provide cryptocurrency transaction related services. This led to a sharp fall in the price of the biggest proof of work cryptocurrencies. For instance, Bitcoin fell 31%, Ethereum fell 44%, Binance Coin fell 32% and Dogecoin fell 30%. Proof of work mining was the next focus, with regulators in popular mining regions citing the use of electricity generated from highly polluting sources such as coal to create Bitcoin and Ethereum.

In September 2021, the Chinese government declared all cryptocurrency transactions of any kind illegal, completing its crackdown on crytocurrency.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, as of 10 January 2021, all cryptocurrency firms, such as exchanges, advisors and professionals that have either a presence, market product or provide services within the UK market must register with the Financial Conduct Authority. Additionally, on 27 June 2021, the financial watchdog demanded that Binance, the world's largest cryptocurrency exchange, cease all regulated activities in the UK. Some commentators believe this is a sign of what is to come in terms of stringent regulation of the UK cryptocurrency market.

South Africa

South Africa, who has seen a large amount of scams related to cryptocurrency is said to be putting a regulatory timeline in place, that will produce a regulatory framework. The largest scam occurred in April 2021, where the two founders of an African-based cryptocurrency exchange called Africrypt, Raees Cajee and Ameer Cajee, disappeared with $3.8 billion worth of Bitcoin. Additionally, Mirror Trading International disappeared with $170 million worth of cryptocurrency in January 2021.

South Korea

In March 2021, South Korea implemented new legislation to strengthen their oversight of digital assets. This legislation requires all digital asset managers, providers and exchanges are registered with the Korea Financial Intelligence Unit in order to operate in South Korea. Registering with this unit requires that all exchanges are certified by the Information Security Management System and that they ensure all customers have real name bank accounts, that the CEO and board members of the exchanges have not been convicted of any crimes and that the exchange holds sufficient levels of deposit insurance to cover losses arising from hacks.

Turkey

Turkey's central bank, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, banned the use of cryptocurrencies and crypto assets for making purchases from 30 April 2021, on the ground that the use of cryptocurrencies for such payments poses significant transaction risks.

El Salvador

On 9 June 2021, El Salvador announced that it will adopt Bitcoin as legal tender, the first country to do so.

Cuba

In August 2021, Cuba recognized cryptocurrency as legal tender, the second country to do so.

Legality

The legal status of cryptocurrencies varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. At least one study has shown that broad generalizations about the use of bitcoin in illicit finance are significantly overstated and that blockchain analysis is an effective crime fighting and intelligence gathering tool. While some countries have explicitly allowed their use and trade, others have banned or restricted it. According to the Library of Congress, an "absolute ban" on trading or using cryptocurrencies applies in eight countries: Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. An "implicit ban" applies in another 15 countries, which include Bahrain, Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Iran, Kuwait, Lesotho, Lithuania, Macau, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Taiwan. In the United States and Canada, state and provincial securities regulators, coordinated through the North American Securities Administrators Association, are investigating "bitcoin scams" and ICOs in 40 jurisdictions.

Various government agencies, departments, and courts have classified bitcoin differently. China Central Bank banned the handling of bitcoins by financial institutions in China in early 2014.

In Russia, though cryptocurrencies are legal, it is illegal to actually purchase goods with any currency other than the Russian ruble. Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.

Cryptocurrencies are a potential tool to evade economic sanctions, for example against Russia, Iran, or Venezuela. Russia also secretly supported Venezuela with the creation of the petro (El Petro), a national cryptocurrency initiated by the Maduro government to obtain valuable oil revenues by circumventing US sanctions.

In August 2018, the Bank of Thailand announced its plans to create its own cryptocurrency, the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

Advertising bans

Cryptocurrency advertisements have been temporarily banned on Facebook, Google, Twitter, Bing, Snapchat, LinkedIn and MailChimp. Chinese internet platforms Baidu, Tencent, and Weibo have also prohibited bitcoin advertisements. The Japanese platform Line and the Russian platform Yandex have similar prohibitions.

U.S. tax status

On 25 March 2014, the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled that bitcoin will be treated as property for tax purposes. Bitcoin is therefore subject to capital gains tax. Researchers from Oxford and Warwick showed that bitcoin has characteristics similar to the precious metals market rather than the fiat currencies, and were hence in agreement with the IRS decision, even if based on different reasons.

In July 2019, the IRS issued letters to cryptocurrency owners instructing them to amend returns and pay taxes.

The legal concern of an unregulated global economy

As the popularity of and demand for online currencies has increased since the inception of bitcoin in 2009, so have concerns that such an unregulated person to person global economy that cryptocurrencies offer may become a threat to society. Concerns abound that altcoins may become tools for anonymous web criminals.

Cryptocurrency networks display a lack of regulation that has been criticized as enabling criminals who seek to evade taxes and launder money. Money laundering issues are also present in regular bank transfers, however with bank-to-bank wire transfers for instance, the account holder must at least provide a proven identity.

Transactions that occur through the use and exchange of these altcoins are independent from formal banking systems, and therefore can make tax evasion simpler for individuals. Since charting taxable income is based upon what a recipient reports to the revenue service, it becomes extremely difficult to account for transactions made using existing cryptocurrencies, a mode of exchange that is complex and difficult to track.

Systems of anonymity that most cryptocurrencies offer can also serve as a simpler means to launder money. Rather than laundering money through an intricate net of financial actors and offshore bank accounts, laundering money through altcoins can be achieved through anonymous transactions.

Loss, theft, and fraud

In February 2014, the world's largest bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, declared bankruptcy. The company stated that it had lost nearly $473 million of their customers' bitcoins likely due to theft, which Mt. Gox blamed on hackers who exploited transaction malleability problems in the network. This was equivalent to approximately 750,000 bitcoins, or about 7% of all the bitcoins in existence. The price of a bitcoin fell from a high of about $1,160 in December to under $400 in February.

Two members of the Silk Road Task Force—a multi-agency federal task force that carried out the U.S. investigation of Silk Road—seized bitcoins for their own use in the course of the investigation. DEA agent Carl Mark Force IV, who attempted to extort Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht ("Dread Pirate Roberts"), pleaded guilty to money laundering, obstruction of justice, and extortion under color of official right, and was sentenced to 6.5 years in federal prison. U.S. Secret Service agent Shaun Bridges pleaded guilty to crimes relating to his diversion of $800,000 worth of bitcoins to his personal account during the investigation, and also separately pleaded guilty to money laundering in connection with another cryptocurrency theft; he was sentenced to nearly eight years in federal prison.

Homero Josh Garza, who founded the cryptocurrency startups GAW Miners and ZenMiner in 2014, acknowledged in a plea agreement that the companies were part of a pyramid scheme, and pleaded guilty to wire fraud in 2015. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission separately brought a civil enforcement action against Garza, who was eventually ordered to pay a judgment of $9.1 million plus $700,000 in interest. The SEC's complaint stated that Garza, through his companies, had fraudulently sold "investment contracts representing shares in the profits they claimed would be generated" from mining.

On 21 November 2017, the Tether cryptocurrency announced they were hacked, losing $31 million in USDT from their primary wallet. The company has 'tagged' the stolen currency, hoping to 'lock' them in the hacker's wallet (making them unspendable). Tether indicates that it is building a new core for its primary wallet in response to the attack in order to prevent the stolen coins from being used.

In May 2018, Bitcoin Gold (and two other cryptocurrencies) were hit by a successful 51% hashing attack by an unknown actor, in which exchanges lost estimated $18m. In June 2018, Korean exchange Coinrail was hacked, losing US$37 million worth of altcoin. Fear surrounding the hack was blamed for a $42 billion cryptocurrency market selloff. On 9 July 2018 the exchange Bancor had $23.5 million in cryptocurrency stolen.

The French regulator Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) lists 15 websites of companies that solicit investment in cryptocurrency without being authorised to do so in France.

A 2020 EU report found that users had lost crypto-assets worth hundreds of millions of US dollars in security breaches at exchanges and storage providers. From 2011 to 2019, between four and 12 breaches were identified a year. In 2019, thefts were reported to have exceeded a value of $1 billion. Stolen assets "typically find their way to illegal markets and are used to fund further criminal activity".

Darknet markets

Properties of cryptocurrencies gave them popularity in applications such as a safe haven in banking crises and means of payment, which also led to the cryptocurrency use in controversial settings in the form of online black markets, such as Silk Road. The original Silk Road was shut down in October 2013 and there have been two more versions in use since then. In the year following the initial shutdown of Silk Road, the number of prominent dark markets increased from four to twelve, while the amount of drug listings increased from 18,000 to 32,000.

Darknet markets present challenges in regard to legality. Cryptocurrency used in dark markets are not clearly or legally classified in almost all parts of the world. In the U.S., bitcoins are labelled as "virtual assets". This type of ambiguous classification puts pressure on law enforcement agencies around the world to adapt to the shifting drug trade of dark markets.

Reception

Speculation, fraud and adoption

Cryptocurrencies have been compared to Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes and economic bubbles, such as housing market bubbles. Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management stated in 2017 that digital currencies were "nothing but an unfounded fad (or perhaps even a pyramid scheme), based on a willingness to ascribe value to something that has little or none beyond what people will pay for it", and compared them to the tulip mania (1637), South Sea Bubble (1720), and dot-com bubble (1999). The New Yorker has explained the debate based on interviews with blockchain founders in an article about the "argument over whether Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the blockchain are transforming the world".

While cryptocurrencies are digital currencies that are managed through advanced encryption techniques, many governments have taken a cautious approach toward them, fearing their lack of central control and the effects they could have on financial security. Regulators in several countries have warned against cryptocurrency and some have taken measures to dissuade users. However, research in 2021 by the UK's financial regulator suggested such warnings went unheard, or ignored. Fewer than one in 10 potential cryptocurrency buyers were aware of consumer warnings on the FCA website, and 12% of crypto users were not aware that their holdings were not protected by statutory compensation.

Additionally, many banks do not offer services for cryptocurrencies and can refuse to offer services to virtual-currency companies. Gareth Murphy, a senior central banking officer has stated "widespread use [of cryptocurrency] would also make it more difficult for statistical agencies to gather data on economic activity, which are used by governments to steer the economy". He cautioned that virtual currencies pose a new challenge to central banks' control over the important functions of monetary and exchange rate policy. While traditional financial products have strong consumer protections in place, there is no intermediary with the power to limit consumer losses if bitcoins are lost or stolen. One of the features cryptocurrency lacks in comparison to credit cards, for example, is consumer protection against fraud, such as chargebacks.

The cryptocurrency community refers to pre-mining, hidden launches, ICO or extreme rewards for the altcoin founders as a deceptive practice. It can also be used as an inherent part of a cryptocurrency's design. Pre-mining means currency is generated by the currency's founders prior to being released to the public.

Paul Krugman, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, has repeated numerous times that it is a bubble that will not last and links it to Tulip mania. American business magnate Warren Buffett thinks that cryptocurrency will come to a bad ending. In October 2017, BlackRock CEO Laurence D. Fink called bitcoin an "index of money laundering". "Bitcoin just shows you how much demand for money laundering there is in the world," he said.

Banks

As the first big Wall Street bank to embrace cryptocurrencies, Morgan Stanley announced on 17 March 2021 that they will be offering access to Bitcoin funds for their wealthy clients through three funds which enable Bitcoin ownership for investors with an aggressive risk tolerance. BNY Mellon on 11 February 2021 announced that it would begin offering cryptocurrency services to its clients.

On 20 April 2021, Venmo added support to its platform to enable customers to buy, hold and sell cryptocurrencies.

Economic freedom

Cryptocurrency presents major strides in economic growth and freedom to individuals such as in developing nations as well as those under economic sanctions. The crypto market is known to be easier to access than traditional banks due to fewer regulations and allows citizens to bypass governments and regulations to mine for cryptocurrency rewards to utilise, trade, and convert for common goods to survive. In countries with high inflation where fiat currency is no longer available to easily utilise to survive, many have turned to cryptocurrency working through online job boards to bypass strict regulations and achieve economic freedom.

Environmental impact

Mining for proof-of-work cryptocurrencies consumes significant quantities of electricity and has a large associated carbon footprint. In 2017, bitcoin mining was estimated to consume 948MW, equivalent to countries the scale of Angola or Panama, respectively ranked 102nd and 103rd in the world. Proof-of-work blockchains such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Monero were estimated to have added 3 to 15 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere in the period from 1 January 2016 to 30 June 2017. By November 2018, Bitcoin was estimated to have an annual energy consumption of 45.8TWh, generating 22.0 to 22.9 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, rivalling nations like Jordan and Sri Lanka.

Critics have also identified a large electronic waste problem in disposing of mining rigs.

Bitcoin is the least energy-efficient cryptocurrency, using 707.6 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction. In comparison, the world's second-largest cryptocurrency, Ethereum, uses 62.56 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction. These two cryptocurrencies use a significant amount of electricity per transaction in comparison to some of their competitors with a smaller market capitalisation. For instance, Dogecoin has a relatively small energy use, using 0.12 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction. Ripple ($XRP) is the world's most energy efficient cryptocurrency, using 0.0079 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction. Cardano uses only 0.5479 kilowatt-hours of electricity per transaction.

Technological limitations

There are also purely technical elements to consider. For example, technological advancement in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin result in high up-front costs to miners in the form of specialized hardware and software. Cryptocurrency transactions are normally irreversible after a number of blocks confirm the transaction. Additionally, cryptocurrency private keys can be permanently lost from local storage due to malware, data loss or the destruction of the physical media. This precludes the cryptocurrency from being spent, resulting in its effective removal from the markets.

Academic studies

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It covers studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.

The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.

Aid agencies

A number of aid agencies have started accepting donations in cryptocurrencies, including the American Red Cross, UNICEF, and the UN World Food Program.

Cryptocurrencies make tracking donations easier and have the potential to allow donors to see how their money is used (financial transparency).

Christopher Fabian, principal adviser at UNICEF Innovation said that UNICEF would uphold existing donor protocols, meaning that those making donations online would have to pass rigorous checks before they were allowed to deposit funds to UNICEF.