| |

| Abbreviation | AAAS |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Founded | September 20, 1848 |

| Focus | Science education and outreach |

| Location | |

Members | 120,000+ |

| Website | www |

Formerly called | Association of American Geologists and Naturalists |

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsibility, and supporting scientific education and science outreach for the betterment of all humanity. AAAS was the first permanent organization established to promote science and engineering nationally and to represent the interests of American researchers from across all scientific fields. It is the world's largest general scientific society, with over 120,000 members, and is the publisher of the well-known scientific journal Science.

History

Creation

The American Association for the Advancement of Science was created on September 20, 1848, at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was a reformation of the Association of American Geologists and Naturalists with the broadened mission to be the first permanent organization to promote science and engineering nationally and to represent the interests of American researchers from across all scientific fields The Society chose William Charles Redfield as their first president because he had proposed the most comprehensive plans for the organization. According to the first constitution which was agreed to at the September 20 meeting, the goal of the society was to promote scientific dialogue in order to allow for greater scientific collaboration. By doing so the association aimed to use resources to conduct science with increased efficiency and allow for scientific progress at a greater rate. The association also sought to increase the resources available to the scientific community through active advocacy of science. There were only 78 members when the AAAS was formed. As a member of the new scientific body, Matthew Fontaine Maury, USN was one of those who attended the first 1848 meeting.

At a meeting held on Friday afternoon, September 22, 1848, Redfield presided, and Matthew Fontaine Maury gave a full scientific report on his Wind and Current Charts. Maury stated that hundreds of ship navigators were now sending abstract logs of their voyages to the United States Naval Observatory. He added, "Never before was such a corps of observers known." But, he pointed out to his fellow scientists, his critical need was for more "simultaneous observations." "The work," Maury stated, "is not exclusively for the benefit of any nation or age." The minutes of the AAAS meeting reveal that because of the universality of this "view on the subject, it was suggested whether the states of Christendom might not be induced to cooperate with their Navies in the undertaking; at least so far as to cause abstracts of their log-books and sea journals to be furnished to Matthew F. Maury, USN, at the Naval Observatory at Washington."

William Barton Rogers, professor at the University of Virginia and later founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, offered a resolution: "Resolved that a Committee of five be appointed to address a memorial to the Secretary of the Navy, requesting his further aid in procuring for Matthew Maury the use of the observations of European and other foreign navigators, for the extension and perfecting of his charts of winds and currents." The resolution was adopted and, in addition to Rogers, the following members of the association were appointed to the committee: Professor Joseph Henry of Washington; Professor Benjamin Peirce of Cambridge, Massachusetts; Professor James H. Coffin of Easton, Pennsylvania, and Professor Stephen Alexander of Princeton, New Jersey. This was scientific cooperation, and Maury went back to Washington with great hopes for the future.

In 1850, the first female members were accepted, they were: astronomer Maria Mitchell, entomologist Margaretta Morris. Science educator Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps was elected in 1859.

Growth and Civil War dormancy

By 1860, membership increased to over 2,000. The AAAS became dormant during the American Civil War; their August 1861 meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, was postponed indefinitely after the outbreak of the first major engagement of the war at Bull Run. The AAAS did not become a permanent casualty of the war.

In 1866, Frederick Barnard presided over the first meeting of the resurrected AAAS at a meeting in New York City. Following the revival of the AAAS, the group had considerable growth. The AAAS permitted all people, regardless of scientific credentials, to join. The AAAS did, however, institute a policy of granting the title of "Fellow of the AAAS" to well-respected scientists within the organization. The years of peace brought the development and expansion of other scientific-oriented groups. The AAAS's focus on the unification of many fields of science under a single organization was in contrast to the many new science organizations founded to promote a single discipline. For example, the American Chemical Society, founded in 1876, promotes chemistry.

In 1863, the US Congress established the National Academy of Sciences, another multidisciplinary sciences organization. It elects members based on recommendations from colleagues and the value of published works.

Twentieth century

Advocacy

Alan I. Leshner, AAAS CEO from 2001 until 2015, published many op-ed articles discussing how many people integrate science and religion in their lives. He has opposed the insertion of non-scientific content, such as creationism or intelligent design, into the scientific curriculum of schools.

In December 2006, the AAAS adopted an official statement on climate change, in which they stated, "The scientific evidence is clear: global climate change caused by human activities is occurring now, and it is a growing threat to society....The pace of change and the evidence of harm have increased markedly over the last five years. The time to control greenhouse gas emissions is now."

In February 2007, the AAAS used satellite images to document human rights abuses in Burma. The next year, AAAS launched the Center for Science Diplomacy to advance both science and the broader relationships among partner countries, by promoting science diplomacy and international scientific cooperation.

In 2012, AAAS published op-eds, held events on Capitol Hill and released analyses of the U.S. federal research-and-development budget, to warn that a budget sequestration would have severe consequences for scientific progress.

Sciences

AAAS covers various areas of sciences and engineering. It has 24 sections, each with a committee and its chair. These committees are also entrusted with the annual evaluation and selection of Fellows. The sections are:

- Agriculture, Food & Renewable Resources

- Anthropology

- Astronomy

- Atmospheric and Hydrospheric Sciences

- Biological Sciences

- Chemistry

- Dentistry and Oral Health Sciences

- Education

- Engineering

- General Interest in Science and Engineering

- Geology and Geography

- History and Philosophy of Science

- Industrial Science and Technology

- Information, Computing, and Communication

- Linguistics and Language Sciences

- Mathematics

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

- Physics

- Psychology

- Social, Economic, and Political Sciences

- Societal Impacts of Science and Engineering

- Statistics

Governance

The most recent Constitution of the AAAS, enacted on January 1, 1973, establishes that the governance of the AAAS is accomplished through four entities: a President, a group of administrative officers, a Council, and a board of directors.

Presidents

Individuals elected to the presidency of the AAAS hold a three-year term in a unique way. The first year is spent as president-elect, the second as president and the third as chairperson of the board of directors. In accordance with the convention followed by the AAAS, presidents are referenced by the year in which they left office.

Geraldine Richmond is the president of AAAS for 2015–16; Phillip Sharp is the board chair; and Barbara A. Schaal is the president-elect. Each took office on the last day of the 2015 AAAS Annual Meeting in February 2015. On the last day of the 2016 AAAS Annual Meeting, February 15, 2016, Richmond will become the chair, Schaal will become the president, and a new president-elect will take office.

Past presidents of AAAS have included some of the most important scientific figures of their time. Among them: explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell (1888); astronomer and physicist Edward Charles Pickering (1912); anthropologist Margaret Mead (1975); and biologist Stephen Jay Gould (2000).

Notable presidents of the AAAS, 1848–2005

- 1849: Joseph Henry

- 1871: Asa Gray

- 1877: Simon Newcomb

- 1880: Joseph Lovering

- 1882: J. William Dawson

- 1886: Edward S. Morse

- 1887: Samuel P. Langley

- 1888: John Wesley Powell

- 1901: Charles Sedgwick Minot

- 1927: Arthur Amos Noyes

- 1929: Robert A. Millikan

- 1931: Franz Boas

- 1934: Edward L. Thorndike

- 1942: Arthur H. Compton

- 1947: Harlow Shapley

- 1951: Kirtley F. Mather

- 1972: Glenn T. Seaborg

- 1975: Margaret Mead

- 1992: Leon M. Lederman

- 2000: Stephen Jay Gould

Administrative officers

There are three classifications of high-level administrative officials that execute the basic, daily functions of the AAAS. These are the executive officer, the treasurer and then each of the AAAS's section secretaries. The current CEO of AAAS and executive publisher of Science magazine is Sudip Parikh. The current Editor in Chief of Science magazine is Holden Thorp.

Sections of the AAAS

The AAAS has 24 "sections" with each section being responsible for a particular concern of the AAAS. There are sections for agriculture, anthropology, astronomy, atmospheric science, biological science, chemistry, dentistry, education, engineering, general interest in science and engineering, geology and geography, the history and philosophy of science, technology, computer science, linguistics, mathematics, medical science, neuroscience, pharmaceutical science, physics, psychology, science and human rights, social and political science, the social impact of science and engineering, and statistics.

Affiliates

AAAS affiliates include 262 societies and academies of science, serving more than 10 million members, from the Acoustical Society of America to the Wildlife Society, as well as non-mainstream groups like the Parapsychological Association.

The Council

The council is composed of the members of the Board of Directors, the retiring section chairmen, elected delegates and affiliated foreign council members. Among the elected delegates there are always at least two members from the National Academy of Sciences and one from each region of the country. The President of the AAAS serves as the Chairperson of the council. Members serve the council for a term of three years.

The council meets annually to discuss matters of importance to the AAAS. They have the power to review all activities of the Association, elect new fellows, adopt resolutions, propose amendments to the Association's constitution and bylaws, create new scientific sections, and organize and aid local chapters of the AAAS. The Council recently has new additions to it from different sections which include many youngsters as well. John Kerry of Chicago is the youngest American in the council and Akhil Ennamsetty of India is the youngest foreign council member.

Board of directors

The board of directors is composed of a chairperson, the president, and the president-elect along with eight elected directors, the executive officer of the association and up to two additional directors appointed by elected officers. Members serve a four-year term except for directors appointed by elected officers, who serve three-year terms.

The current chairman is Gerald Fink, Margaret and Herman Sokol Professor at Whitehead Institute, MIT. Fink will serve in the post until the end of the 2016 AAAS Annual Meeting, 15 February 2016. (The chairperson is always the immediate past-president of AAAS.)

The board of directors has a variety of powers and responsibilities. It is charged with the administration of all association funds, publication of a budget, appointment of administrators, proposition of amendments, and determining the time and place of meetings of the national association. The board may also speak publicly on behalf of the association. The board must also regularly correspond with the council to discuss their actions.

AAAS Fellows

The AAAS council elects every year, its members who are distinguished scientifically, to the grade of fellow (FAAAS). Election to AAAS is an honor bestowed by their peers and elected fellows are presented with a certificate and rosette pin. To limit the effects and tolerance of sexual harassment in the sciences, starting 15 October 2018, a Fellow's status can be revoked "in cases of proven scientific misconduct, serious breaches of professional ethics, or when the Fellow in the view of the AAAS otherwise no longer merits the status of Fellow."

Meetings

Formal meetings of the AAAS are numbered consecutively, starting with the first meeting in 1848. Meetings were not held 1861–1865 during the American Civil War, and also 1942–1943 during World War II. Since 1946, one meeting has occurred annually, now customarily in February.

Awards and fellowships

Each year, the AAAS gives out a number of honorary awards, most of which focus on science communication, journalism, and outreach – sometimes in partnership with other organizations. The awards recognize "scientists, journalists, and public servants for significant contributions to science and to the public's understanding of science". The awards are presented each year at the association's annual meeting.

The AAAS also offers a number of fellowship programs.

Currently active awards include

- Award for Science and Diplomacy

- Early Career Award for Public Engagement with Science

- The Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Children's Science News

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Magazine

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Newspapers (< 100,000 daily circulation)

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Newspapers (> 100,000 daily circulation)

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Online

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Radio

- Kavli Science Journalism Awards – Television

- Leadership in Science Education Prize for High School Teachers

- Marion Milligan Mason Award: Women in the Chemical Sciences

- Mani L. Bhaumik Award for Public Engagement with Science (previously AAAS Award for Public Understanding of Science and Technology, established 1987)

- Mentor Award

- Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement

- Newcomb Cleveland Prize

- Philip Hauge Abelson Prize

- Public Engagement with Science Award

- Scientific Freedom and Responsibility Award

- John McGovern Lecture

- William D. Carey Lecture

- Golden Goose Award

Publications

The society's flagship publication is Science, a weekly interdisciplinary scientific journal. Other peer-reviewed journals published by the AAAS in the "Science family of journals" are Science Signaling, Science Translational Medicine, Science Immunology, Science Robotics and the interdisciplinary Science Advances. They also publish the non-peer-reviewed Science & Diplomacy. The society previously published the review journal Science Books & Films (SB&F). AAAS also publishes on behalf of other organizations through the Science Partner Journals (SPJ) program, with a focus on online-only open access journals.

SciLine

SciLine is a philanthropically funded and editorially independent service for journalists and scientists. Its launch was announced in an October 27, 2017 article in Science by founding director Rick Weiss, former communications chief at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and science reporter at the Washington Post. Its stated mission is to increase the amount and quality of research-backed evidence in news stories by connecting U.S. journalists to scientists and to validated scientific information.

Reporters in the United States can access SciLine's services, which include expert-matching, general media briefings, expert quote sheets, and quick fact sheets. As of July 2021, SciLine had fulfilled approximately 2,000 requests from 650 journalists through its expert-matching service.

SciLine's financial supporters include the Quadrivium Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Rita Allen Foundation, and the Heinz Endowments. AAAS provides in-kind support.

EurekAlert!

In 1996, AAAS launched the EurekAlert! website, an editorially independent, non-profit news release distribution service covering all areas of science, medicine and technology. EurekAlert! provides news in English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, Japanese, and, from 2007, in Chinese.

Working staff journalists and freelancers who meet eligibility guidelines can access the latest studies before publication and obtain embargoed information in compliance with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's Regulation Fair Disclosure policy. By early 2018, more than 14,000 reporters from more than 90 countries have registered for free access to embargoed materials. More than 5,000 active public information officers from 2,300 universities, academic journals, government agencies, and medical centers are credentialed to provide new releases to reporters and the public through the system.

In 1998, European science organizations countered Eurekalert! with a press release distribution service AlphaGalileo.

EurekAlert! has fallen under criticism for lack of press release standards and for generating churnalism.

![{\displaystyle \alpha \in [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/daf3c62599ea71319c85f715c9e590d2bab2d036)

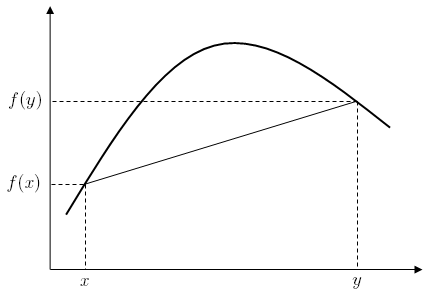

![{\displaystyle f(y)\leq f(x)+f'(x)[y-x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ad4b94b94e56ebbdad4a9badaa4412142b032c08)

![{\displaystyle [0,\pi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e2a912eda6ef1afe46a81b518fe9da64a832751)