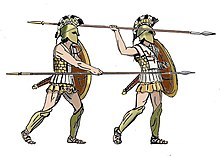

Hoplites (/ˈhɒplaɪts/ HOP-lytes) (Ancient Greek: ὁπλῖται, romanized: hoplîtai [hoplîːtai̯]) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldiers from acting alone, for this would compromise the formation and minimize its strengths. The hoplites were primarily represented by free citizens – propertied farmers and artisans – who were able to afford a linen or bronze armour suit and weapons (estimated at a third to a half of its able-bodied adult male population). It also appears in the stories of Homer, but it is thought that its use began in earnest around the 7th century BC, when weapons became cheap during the Iron Age and ordinary citizens were able to provide their own weapons. Most hoplites were not professional soldiers and often lacked sufficient military training. Some states maintained a small elite professional unit, known as the epilektoi or logades (means "the chosen") since they were picked from the regular citizen infantry. These existed at times in Athens, Sparta, Argos, Thebes, and Syracuse, among other places. Hoplite soldiers made up the bulk of ancient Greek armies.

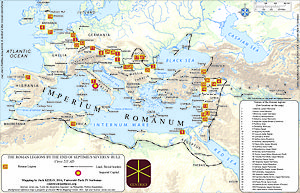

In the 8th or 7th century BC, Greek armies adopted the phalanx formation. The formation proved successful in defeating the Persians when employed by the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC during the First Greco-Persian War. The Persian archers and light troops who fought in the Battle of Marathon failed because their bows were too weak for their arrows to penetrate the wall of Greek shields of the phalanx formation. The phalanx was also employed by the Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC and at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC during the Second Greco-Persian War.

The word hoplite (Greek: ὁπλίτης hoplítēs; pl. ὁπλῖται hoplĩtai) derives from hoplon (ὅπλον : hóplon; plural hópla ὅπλα), referring to the hoplite's equipment. In the modern Hellenic Army, the word hoplite (Greek: oπλίτης : oplítîs) is used to refer to an infantryman.

Warfare

The fragmented political structure of Ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict, but at the same time limited the scale of warfare. Limited manpower did not allow most Greek city-states to form large armies which could operate for long periods because they were generally not formed from professional soldiers. Most soldiers had careers as farmers or workers and returned to these professions after the campaign. All hoplites were expected to take part in any military campaign when called for duty by leaders of the state. The Lacedaemonian citizens of Sparta were renowned for their lifelong combat training and almost mythical military prowess, while their greatest adversaries, the Athenians, were exempted from service only after the age of 60. This inevitably reduced the potential duration of campaigns and often resulted in the campaign season being restricted to one summer.

Armies generally marched directly to their destination, and in some cases the battlefield was agreed to by the contestants in advance. Battles were fought on level ground, and hoplites preferred to fight with high terrain on both sides of the phalanx so the formation could not be flanked. An example of this was the Battle of Thermopylae, where the Spartans specifically chose a narrow coastal pass to make their stand against the massive Persian army. The vastly outnumbered Greeks held off the Persians for seven days.

When battles occurred, they were usually set piece and intended to be decisive. The battlefield would be flat and open to facilitate phalanx warfare. These battles were usually short and required a high degree of discipline. At least in the early classical period, when cavalry was present, its role was restricted to protection of the flanks of the phalanx, pursuit of a defeated enemy, and covering a retreat if required. Light infantry and missile troops took part in the battles but their role was less important. Before the opposing phalanxes engaged, the light troops would skirmish with the enemy's light forces, and then protect the flanks and rear of the phalanx.

The military structure created by the Spartans was a rectangular phalanx formation. The formation was organized from eight to ten rows deep and could cover a front of a quarter of a mile or more if sufficient hoplites were available. The two lines would close to a short distance to allow effective use of their spears, while the psiloi threw stones and javelins from behind their lines. The shields would clash and the first lines (protostates) would stab at their opponents, at the same time trying to keep in position. The ranks behind them would support them with their own spears and the mass of their shields gently pushing them, not to force them into the enemy formation but to keep them steady and in place. The soldiers in the back provided motivation to the ranks in the front being that most hoplites were close community members. At certain points, a command would be given to the phalanx or a part thereof to collectively take a certain number of steps forward (ranging from half to multiple steps). This was the famed othismos.

At this point, the phalanx would put its collective weight to push back the enemy line and thus create fear and panic among its ranks. There could be multiple such instances of attempts to push, but it seems from the accounts of the ancients that these were perfectly orchestrated and attempted organized en masse. Once one of the lines broke, the troops would generally flee from the field, sometimes chased by psiloi, peltasts, or light cavalry.

If a hoplite escaped, he would sometimes be forced to drop his cumbersome aspis, thereby disgracing himself to his friends and family (becoming a ripsaspis, one who threw his shield). To lessen the number of casualties inflicted by the enemy during battles, soldiers were positioned to stand shoulder to shoulder with their aspis. The hoplites' most prominent citizens and generals led from the front. Thus, the war could be decided by a single battle.

Individual hoplites carried their shields on their left arm, protecting themselves and the soldier to the left. This meant that the men at the extreme right of the phalanx were only half-protected. In battle, opposing phalanxes would exploit this weakness by attempting to overlap the enemy's right flank. It also meant that, in battle, a phalanx would tend to drift to the right (as hoplites sought to remain behind the shield of their neighbour). The most experienced hoplites were often placed on the right side of the phalanx, to counteract these problems. According to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartans, "a man carried a shield for the sake of the whole line".

The phalanx is an example of a military formation in which single combat and other individualistic forms of battle were suppressed for the good of the whole. In earlier Homeric, Dark Age combat, the words and deeds of supremely powerful heroes turned the tide of battle. Instead of having individual heroes, hoplite warfare relied heavily on the community and unity of soldiers. With friends and family pushing on either side and enemies forming a solid wall of shields in front, the hoplite had little opportunity for feats of technique and weapon skill, but great need for commitment and mental toughness. By forming a human wall to provide a powerful defensive armour, the hoplites became much more effective while suffering fewer casualties. The hoplites had a lot of discipline and were taught to be loyal and trustworthy. They had to trust their neighbours for mutual protection, so a phalanx was only as strong as its weakest elements. Its effectiveness depended on how well the hoplites could maintain this formation in combat, and how well they could stand their ground, especially when engaged against another phalanx. The more disciplined and courageous the army, the more likely it was to win. Often engagements between various city-states of Greece would be resolved by one side fleeing after their phalanx had broken formation.

As important as unity among the ranks was in phalanx warfare, individual fighting skill played a role in battle. Hoplites' shields were not locked all of the time. Throughout many points of the fight there were periods where the hoplites separated as far as two to three feet apart in order to have room to swing their shields and swords at the enemy. This led to individual prowess being more important than previously realized by some historians. It would have been nearly impossible to swing both shield and sword if the man next to you is practically touching. One piece of evidence of this is the picking of individual champions after each battle was fought. This is most evident in Herodotus' account of the Battle of Thermopylae. "Although great valor was displayed by the entire corps of Spartans and Thespians, the man who proved himself best was a Spartan Officer named Dienekes". The brothers Alpheos and Maron were also honored for their battlefield prowess as well. This is just one example of an ancient historian giving credit to a few individual soldiers and the individuality of phalanx warfare.

Equipment

Body armour

Each hoplite provided his own equipment. Thus, only those who could afford such weaponry fought as hoplites. As with the Roman Republican army it was the middle classes who formed the bulk of the infantry. Equipment was not standardized, although there were doubtless trends in general designs over time, and between city-states. Hoplites had customized armour, the shield was decorated with family or clan emblems, although in later years these were replaced by symbols or monograms of the city states. The equipment might be passed down in families, as it was expensive to manufacture.

The hoplite army consisted of heavy infantrymen. Their armour, also called panoply, was sometimes made of full bronze for those who could afford it, weighing nearly 32 kilograms (70 lb), although linen armor now known as linothorax was more common since it was cost-effective and provided decent protection. The average farmer-peasant hoplite could not afford any armor and typically carried only a shield, a spear, and perhaps a helmet plus a secondary weapon. The richer upper-class hoplites typically had a bronze cuirass of either the bell or muscled variety, a bronze helmet with cheekplates, as well as greaves and other armour. The design of helmets used varied through time. The Corinthian helmet was at first standardized and was a successful design. Later variants included the Chalcidian helmet, a lightened version of the Corinthian helmet, and the simple Pilos helmet worn by the later hoplites. Often the helmet was decorated with one, sometimes more horsehair crests, and/or bronze animal horns and ears. Helmets were often painted as well. The Thracian helmet had a large visor to further increase protection. In later periods, linothorax was also used, as it is tougher and cheaper to produce. The linen was 0.5-centimetre (0.20 in) thick.

By contrast with hoplites, other contemporary infantry (e.g., Persian) tended to wear relatively light armour, wicker shields, and were armed with shorter spears, javelins, and bows. The most famous are the Peltasts, light-armed troops who wore no armour and were armed with a light shield, javelins and a short sword. The Athenian general Iphicrates developed a new type of armour and arms for his mercenary army, which included light linen armour, smaller shields and longer spears, whilst arming his Peltasts with larger shields, helmets and a longer spear, thus enabling them to defend themselves more easily against hoplites. With this new type of army he defeated a Spartan army in 392 BC. The arms and armour described above were most common for hoplites.

Shield

Hoplites carried a large concave shield called an aspis (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a hoplon), measuring between 80 and 100 centimetres (31 and 39 inches) in diameter and weighing between 6.5 and 8 kg (14 and 18 lb). This large shield was made possible partly by its shape, which allowed it to be supported on the shoulder. The shield was assembled in three layers: the center layer was made of thick wood, the outside layer facing the enemy was made of bronze, and leather comprised the inside of the shield. The revolutionary part of the shield was the grip. Known as an Argive grip, it placed the handle at the edge of the shield, and was supported by a leather fastening (for the forearm) at the centre. These two points of contact eliminated the possibility of the shield swaying to the side after being struck, and as a result soldiers rarely lost their shields. This allowed the hoplite soldier more mobility with the shield, as well as the ability to capitalize on its offensive capabilities and better support the phalanx. The large shields, designed for pushing ahead, were the most essential equipment for the hoplites.

Spear

The main offensive weapon used was a 2.5–4.5-metre (8.2–14.8 ft) long and 2.5-centimetre (1 in) in diameter spear called a doru, or dory. It was held with the right hand, with the left hand holding the hoplite's shield. Soldiers usually held their spears in an underhand position when approaching but once they came into close contact with their opponents, they were held in an overhand position ready to strike. The spearhead was usually a curved leaf shape, while the rear of the spear had a spike called a sauroter ("lizard-killer") which was used to stand the spear in the ground (hence the name). It was also used as a secondary weapon if the main shaft snapped, or for the rear ranks to finish off fallen opponents as the phalanx advanced over them. In addition to being used as a secondary weapon, the sauroter doubled to balance the spear, but not for throwing purposes. It is a matter of contention, among historians, whether the hoplite used the spear overarm or underarm. Held underarm, the thrusts would have been less powerful but under more control, and vice versa. It seems likely that both motions were used, depending on the situation. If attack was called for, an overarm motion was more likely to break through an opponent's defence. The upward thrust is more easily deflected by armour due to its lesser leverage. When defending, an underarm carry absorbed more shock and could be 'couched' under the shoulder for maximum stability. An overarm motion would allow more effective combination of the aspis and doru if the shield wall had broken down, while the underarm motion would be more effective when the shield had to be interlocked with those of one's neighbours in the battle-line. Hoplites in the rows behind the lead would almost certainly have made overarm thrusts. The rear ranks held their spears underarm, and raised their shields upwards at increasing angles. This was an effective defence against missiles, deflecting their force.

Sword

Hoplites also carried a sword, mostly a short sword called a xiphos, but later also longer and heavier types. The short sword was a secondary weapon, used if or when their spears were broken or lost, or if the phalanx broke rank. The xiphos usually had a blade around 60 centimetres (24 in) long; however, those used by the Spartans were often only 30–45 centimetres long. This very short xiphos would be very advantageous in the press that occurred when two lines of hoplites met, capable of being thrust through gaps in the shieldwall into an enemy's unprotected groin or throat, while there was no room to swing a longer sword. Such a small weapon would be particularly useful after many hoplites had started to abandon body armour during the Peloponnesian War. Hoplites could also alternatively carry the kopis, a heavy knife with a forward-curving blade. The scabbard of the sword was called koleos (κολεός).

Theories on the transition to fighting in the phalanx

Dark Age warfare transitioned into hoplite warfare in the 8th century BC. Historians and researchers have debated the reason and speed of the transition for centuries. So far 3 popular theories exist:

Gradualist theory

Developed by Anthony Snodgrass, the Gradualist Theory states that the hoplite style of battle developed in a series of steps as a result of innovations in armour and weaponry. Chronologically dating the archeological findings of hoplite armour and using the findings to approximate the development of the phalanx formation, Snodgrass claims that the transition took approximately 100 years to complete from 750 to 650 BC. The progression of the phalanx took time because as the phalanx matured it required denser formations that made the elite warriors recruit Greek citizens. The large amounts of hoplite armour needed to then be distributed to the populations of Greek citizens only increased the time for the phalanx to be implemented. Snodgrass believes, only once the armour was in place that the phalanx formation became popular.

Rapid adoption theory

The Rapid Adaptation model was developed by historians Paul Cartledge and Victor Hanson. They believed that the phalanx was created individually by military forces, but was so effective that others had to immediately adapt their way of war to combat the formation. Rapid Adoptionists propose that the double grip shield that was required for the phalanx formation was so constricting in mobility that once it was introduced, Dark Age, free flowing warfare was inadequate to fight against the hoplites only escalating the speed of the transition. Quickly, the phalanx formation and hoplite armour became widely used throughout Ancient Greece. Cartledge and Hanson estimate the transition took place from 725 to 675 BC.

Extended gradualist theory

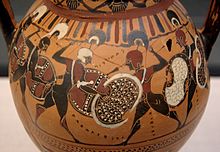

Developed by Hans Van Wees, the Extended Gradualist theory is the most lengthy of the three popular transition theories. Van Wees depicts iconography found on pots of the Dark Ages believing that the foundation of the phalanx formation was birthed during this time. Specifically, he uses an example of the Chigi Vase to point out that hoplite soldiers were carrying normal spears as well as javelins on their backs. Matured hoplites did not carry long-range weapons including javelins. The Chigi vase is important for our knowledge of the hoplite soldier because it is one if not the only representation of the hoplite formation, known as the phalanx, in Greek art. This led Van Wees to believe that there was a transitional period from long-range warfare of the Dark Ages to the close combat of hoplite warfare. Some other evidence of a transitional period lies within the text of Spartan poet Tyrtaios, who wrote, "…will they draw back for the pounding [of the missiles, no,] despite the battery of great hurl-stones, the helmets shall abide the rattle [of war unbowed]". At no point in other texts does Tyrtaios discuss missiles or rocks, making another case for a transitional period in which hoplite warriors had some ranged capabilities. Extended Gradualists argue that hoplite warriors did not fight in a true phalanx until the 5th century BC. Making estimations of the speed of the transition reached as long as 300 years, from 750 to 450 BC.

History

Ancient Greece

The exact time when hoplite warfare was developed is uncertain, the prevalent theory being that it was established sometime during the 8th or 7th century BC, when the "heroic age was abandoned and a far more disciplined system introduced" and the Argive shield became popular. Peter Krentz argues that "the ideology of hoplitic warfare as a ritualized contest developed not in the 7th century [BC], but only after 480, when non-hoplite arms began to be excluded from the phalanx". Anagnostis Agelarakis, based on recent archaeo-anthropological discoveries of the earliest monumental polyandrion (communal burial of male warriors) at Paros Island in Greece, unveiled a last quarter of the 8th century BC date for a hoplitic phalangeal military organization.

The rise and fall of hoplite warfare was tied to the rise and fall of the city-state. As discussed above, hoplites were a solution to the armed clashes between independent city-states. As Greek civilization found itself confronted by the world at large, particularly the Persians, the emphasis in warfare shifted. Confronted by huge numbers of enemy troops, individual city-states could not realistically fight alone. During the Greco-Persian Wars (499–448 BC), alliances between groups of cities (whose composition varied over time) fought against the Persians. This drastically altered the scale of warfare and the numbers of troops involved. The hoplite phalanx proved itself far superior to the Persian infantry at such conflicts as the Battle of Marathon, Thermopylae, and the Battle of Plataea.

During this period, Athens and Sparta rose to a position of political eminence in Greece, and their rivalry in the aftermath of the Persian wars brought Greece into renewed internal conflict. The Peloponnesian War was on a scale unlike conflicts before. Fought between leagues of cities, dominated by Athens and Sparta respectively, the pooled manpower and financial resources allowed a diversification of warfare. Hoplite warfare was in decline. There were three major battles in the Peloponnesian War, and none proved decisive. Instead there was increased reliance on navies, skirmishers, mercenaries, city walls, siege engines, and non-set piece tactics. These reforms made wars of attrition possible and greatly increased the number of casualties. In the Persian war, hoplites faced large numbers of skirmishers and missile-armed troops, and such troops (e.g., peltasts) became much more commonly used by the Greeks during the Peloponnesian War. As a result, hoplites began wearing less armour, carrying shorter swords, and in general adapting for greater mobility. This led to the development of the ekdromos light hoplite.

Many famous personalities, philosophers, artists, and poets fought as hoplites.

According to Nefiodkin, fighting against Greek heavy infantry during the Greco-Persian Wars inspired the Persians to introduce scythed chariots.

Sparta

Sparta is one of the most famous city-states, along with Athens, which had a unique position in ancient Greece. Contrary to other city states, the free citizens of Sparta served as hoplites their entire lives, training and exercising in peacetime, which gave Sparta a professional standing army. Often small, numbering around 6000 at its peak to no more than 1000 soldiers at lowest point, divided into six mora or battalions, the Spartan army was feared for its discipline and ferocity. Military service was the primary duty of Spartan men, and Spartan society was organized around its army.

Military service for hoplites lasted until the age of 40, and sometimes until 60 years of age, depending on a man's physical ability to perform on the battlefield.

Macedonia

Later in the hoplite era, more sophisticated tactics were developed, in particular by the Theban general Epaminondas. These tactics inspired the future king Philip II of Macedon, who was at the time a hostage in Thebes, to develop a new type of infantry, the Macedonian phalanx. After the Macedonian conquests of the 4th century BC, the hoplite was slowly abandoned in favour of the phalangite, armed in the Macedonian fashion, in the armies of the southern Greek states. Although clearly a development of the hoplite, the Macedonian phalanx was tactically more versatile, especially used in the combined arms tactics favoured by the Macedonians. These forces defeated the last major hoplite army, at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), after which Athens and its allies joined the Macedonian empire.

While Alexander's army mainly fielded Pezhetairoi (= Foot Companions) as his main force, his army also included some classic hoplites, either provided by the League of Corinth or from hired mercenaries. Beside these units, the Macedonians also used the so-called Hypaspists, an elite force of units possibly originally fighting as hoplites and used to guard the exposed right wing of Alexander's phalanx.

Hoplite-style warfare outside Greece

Hoplite-style warfare was influential, and influenced several other nations in the Mediterranean. Hoplite warfare was the dominant fighting style on much of the Italian Peninsula until the early 3rd century BC, employed by both the Etruscans and the Early Roman army, though scutum infantry had existed for centuries and some groups fielded both. The Romans later standardized their fighting style to a more flexible maniple organization, which was more versatile on rough terrain like that of the Apennines. Roman equipment also changed, trading spears for swords and heavy javelins (pilum). In the end only the triarii would keep a long spear (hasta) as their main weapon. The triarii would still fight in a traditional phalanx formation. Though this combination or similar was popular in much of Italy, some continued to fight as hoplites. Mercenaries serving under Pyrrhus of Epirus or Hannibal (namely Lucanians) were equipped and fought as hoplites.

Early in its history, Ancient Carthage also equipped its troops as Greek hoplites, in units such as the Sacred Band of Carthage. Many Greek hoplite mercenaries fought in foreign armies, such as Carthage and Achaemenid Empire, where it is believed by some that they inspired the formation of the Cardaces. Some hoplites served under the Illyrian king Bardylis in the 4th century. The Illyrians were known to import many weapons and tactics from the Greeks.

The Diadochi imported the Greek phalanx to their kingdoms. Though they mostly fielded Greek citizens or mercenaries, they also armed and drilled local natives as hoplites or rather Macedonian phalanx, like the Machimoi of the Ptolemaic army.

Hellenistic period

The Greek armies of the Hellenistic period mostly fielded troops in the fashion of the Macedonian phalanx. Many armies of mainland Greece retained hoplite warfare. Besides classical hoplites Hellenistic nations began to field two new types of hoplites, the Thureophoroi and the Thorakitai. They developed when Greeks adopted the Galatian Thureos shield, of an oval shape that was similar to the shields of the Romans, but flatter. The Thureophoroi were armed with a long thrusting spear, a short sword and, if needed, javelins. While the Thorakitai were similar to the Thureophoroi, they were more heavily armoured, as their name implies, usually wearing a mail shirt. These troops were used as a link between the light infantry and the phalanx, a form of medium infantry to bridge the gaps.