A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime because the only ways of writing it as a product, 1 × 5 or 5 × 1, involve 5 itself. However, 4 is composite because it is a product (2 × 2) in which both numbers are smaller than 4. Primes are central in number theory because of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic: every natural number greater than 1 is either a prime itself or can be factorized as a product of primes that is unique up to their order.

The property of being prime is called primality. A simple but slow method of checking the primality of a given number , called trial division, tests whether is a multiple of any integer between 2 and . Faster algorithms include the Miller–Rabin primality test, which is fast but has a small chance of error, and the AKS primality test, which always produces the correct answer in polynomial time but is too slow to be practical. Particularly fast methods are available for numbers of special forms, such as Mersenne numbers. As of December 2018 the largest known prime number is a Mersenne prime with 24,862,048 decimal digits.

There are infinitely many primes, as demonstrated by Euclid around 300 BC. No known simple formula separates prime numbers from composite numbers. However, the distribution of primes within the natural numbers in the large can be statistically modelled. The first result in that direction is the prime number theorem, proven at the end of the 19th century, which says that the probability of a randomly chosen large number being prime is inversely proportional to its number of digits, that is, to its logarithm.

Several historical questions regarding prime numbers are still unsolved. These include Goldbach's conjecture, that every even integer greater than 2 can be expressed as the sum of two primes, and the twin prime conjecture, that there are infinitely many pairs of primes that differ by two. Such questions spurred the development of various branches of number theory, focusing on analytic or algebraic aspects of numbers. Primes are used in several routines in information technology, such as public-key cryptography, which relies on the difficulty of factoring large numbers into their prime factors. In abstract algebra, objects that behave in a generalized way like prime numbers include prime elements and prime ideals.

Definition and examples

A natural number (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, etc.) is called a prime number (or a prime) if it is greater than 1 and cannot be written as the product of two smaller natural numbers. The numbers greater than 1 that are not prime are called composite numbers. In other words, is prime if items cannot be divided up into smaller equal-size groups of more than one item, or if it is not possible to arrange dots into a rectangular grid that is more than one dot wide and more than one dot high. For example, among the numbers 1 through 6, the numbers 2, 3, and 5 are the prime numbers, as there are no other numbers that divide them evenly (without a remainder). 1 is not prime, as it is specifically excluded in the definition. 4 = 2 × 2 and 6 = 2 × 3 are both composite.

The divisors of a natural number are the natural numbers that divide evenly. Every natural number has both 1 and itself as a divisor. If it has any other divisor, it cannot be prime. This leads to an equivalent definition of prime numbers: they are the numbers with exactly two positive divisors. Those two are 1 and the number itself. As 1 has only one divisor, itself, it is not prime by this definition. Yet another way to express the same thing is that a number is prime if it is greater than one and if none of the numbers divides evenly.

The first 25 prime numbers (all the prime numbers less than 100) are:

- 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97 (sequence A000040 in the OEIS).

No even number greater than 2 is prime because any such number can be expressed as the product . Therefore, every prime number other than 2 is an odd number, and is called an odd prime. Similarly, when written in the usual decimal system, all prime numbers larger than 5 end in 1, 3, 7, or 9. The numbers that end with other digits are all composite: decimal numbers that end in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 are even, and decimal numbers that end in 0 or 5 are divisible by 5.

The set of all primes is sometimes denoted by (a boldface capital P) or by (a blackboard bold capital P).

History

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, from around 1550 BC, has Egyptian fraction expansions of different forms for prime and composite numbers. However, the earliest surviving records of the explicit study of prime numbers come from ancient Greek mathematics. Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC) proves the infinitude of primes and the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, and shows how to construct a perfect number from a Mersenne prime. Another Greek invention, the Sieve of Eratosthenes, is still used to construct lists of primes.

Around 1000 AD, the Islamic mathematician Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) found Wilson's theorem, characterizing the prime numbers as the numbers that evenly divide . He also conjectured that all even perfect numbers come from Euclid's construction using Mersenne primes, but was unable to prove it. Another Islamic mathematician, Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi, observed that the sieve of Eratosthenes can be sped up by considering only the prime divisors up to the square root of the upper limit. Fibonacci took the innovations from Islamic mathematics to Europe. His book Liber Abaci (1202) was the first to describe trial division for testing primality, again using divisors only up to the square root.

In 1640 Pierre de Fermat stated (without proof) Fermat's little theorem (later proved by Leibniz and Euler). Fermat also investigated the primality of the Fermat numbers , and Marin Mersenne studied the Mersenne primes, prime numbers of the form with itself a prime. Christian Goldbach formulated Goldbach's conjecture, that every even number is the sum of two primes, in a 1742 letter to Euler. Euler proved Alhazen's conjecture (now the Euclid–Euler theorem) that all even perfect numbers can be constructed from Mersenne primes. He introduced methods from mathematical analysis to this area in his proofs of the infinitude of the primes and the divergence of the sum of the reciprocals of the primes . At the start of the 19th century, Legendre and Gauss conjectured that as tends to infinity, the number of primes up to is asymptotic to , where is the natural logarithm of . A weaker consequence of this high density of primes was Bertrand's postulate, that for every there is a prime between and , proved in 1852 by Pafnuty Chebyshev. Ideas of Bernhard Riemann in his 1859 paper on the zeta-function sketched an outline for proving the conjecture of Legendre and Gauss. Although the closely related Riemann hypothesis remains unproven, Riemann's outline was completed in 1896 by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin, and the result is now known as the prime number theorem. Another important 19th century result was Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions, that certain arithmetic progressions contain infinitely many primes.

Many mathematicians have worked on primality tests for numbers larger than those where trial division is practicably applicable. Methods that are restricted to specific number forms include Pépin's test for Fermat numbers (1877), Proth's theorem (c. 1878), the Lucas–Lehmer primality test (originated 1856), and the generalized Lucas primality test.

Since 1951 all the largest known primes have been found using these tests on computers. The search for ever larger primes has generated interest outside mathematical circles, through the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search and other distributed computing projects. The idea that prime numbers had few applications outside of pure mathematics was shattered in the 1970s when public-key cryptography and the RSA cryptosystem were invented, using prime numbers as their basis.

The increased practical importance of computerized primality testing and factorization led to the development of improved methods capable of handling large numbers of unrestricted form. The mathematical theory of prime numbers also moved forward with the Green–Tao theorem (2004) that there are arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions of prime numbers, and Yitang Zhang's 2013 proof that there exist infinitely many prime gaps of bounded size.

Primality of one

Most early Greeks did not even consider 1 to be a number, so they could not consider its primality. A few scholars in the Greek and later Roman tradition, including Nicomachus, Iamblichus, Boethius, and Cassiodorus also considered the prime numbers to be a subdivision of the odd numbers, so they did not consider 2 to be prime either. However, Euclid and a majority of the other Greek mathematicians considered 2 as prime. The medieval Islamic mathematicians largely followed the Greeks in viewing 1 as not being a number. By the Middle Ages and Renaissance, mathematicians began treating 1 as a number, and some of them included it as the first prime number. In the mid-18th century Christian Goldbach listed 1 as prime in his correspondence with Leonhard Euler; however, Euler himself did not consider 1 to be prime. In the 19th century many mathematicians still considered 1 to be prime, and lists of primes that included 1 continued to be published as recently as 1956.

If the definition of a prime number were changed to call 1 a prime, many statements involving prime numbers would need to be reworded in a more awkward way. For example, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic would need to be rephrased in terms of factorizations into primes greater than 1, because every number would have multiple factorizations with any number of copies of 1. Similarly, the sieve of Eratosthenes would not work correctly if it handled 1 as a prime, because it would eliminate all multiples of 1 (that is, all other numbers) and output only the single number 1. Some other more technical properties of prime numbers also do not hold for the number 1: for instance, the formulas for Euler's totient function or for the sum of divisors function are different for prime numbers than they are for 1. By the early 20th century, mathematicians began to agree that 1 should not be listed as prime, but rather in its own special category as a "unit".

Elementary properties

Unique factorization

Writing a number as a product of prime numbers is called a prime factorization of the number. For example:

The terms in the product are called prime factors. The same prime factor may occur more than once; this example has two copies of the prime factor When a prime occurs multiple times, exponentiation can be used to group together multiple copies of the same prime number: for example, in the second way of writing the product above, denotes the square or second power of

The central importance of prime numbers to number theory and mathematics in general stems from the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. This theorem states that every integer larger than 1 can be written as a product of one or more primes. More strongly, this product is unique in the sense that any two prime factorizations of the same number will have the same numbers of copies of the same primes, although their ordering may differ. So, although there are many different ways of finding a factorization using an integer factorization algorithm, they all must produce the same result. Primes can thus be considered the "basic building blocks" of the natural numbers.

Some proofs of the uniqueness of prime factorizations are based on Euclid's lemma: If is a prime number and divides a product of integers and then divides or divides (or both). Conversely, if a number has the property that when it divides a product it always divides at least one factor of the product, then must be prime.

Infinitude

There are infinitely many prime numbers. Another way of saying this is that the sequence

- 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, ...

of prime numbers never ends. This statement is referred to as Euclid's theorem in honor of the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, since the first known proof for this statement is attributed to him. Many more proofs of the infinitude of primes are known, including an analytical proof by Euler, Goldbach's proof based on Fermat numbers, Furstenberg's proof using general topology, and Kummer's elegant proof.

Euclid's proof shows that every finite list of primes is incomplete. The key idea is to multiply together the primes in any given list and add If the list consists of the primes this gives the number

By the fundamental theorem, has a prime factorization

with one or more prime factors. is evenly divisible by each of these factors, but has a remainder of one when divided by any of the prime numbers in the given list, so none of the prime factors of can be in the given list. Because there is no finite list of all the primes, there must be infinitely many primes.

The numbers formed by adding one to the products of the smallest primes are called Euclid numbers. The first five of them are prime, but the sixth,

is a composite number.

Formulas for primes

There is no known efficient formula for primes. For example, there is no non-constant polynomial, even in several variables, that takes only prime values. However, there are numerous expressions that do encode all primes, or only primes. One possible formula is based on Wilson's theorem and generates the number 2 many times and all other primes exactly once. There is also a set of Diophantine equations in nine variables and one parameter with the following property: the parameter is prime if and only if the resulting system of equations has a solution over the natural numbers. This can be used to obtain a single formula with the property that all its positive values are prime.

Other examples of prime-generating formulas come from Mills' theorem and a theorem of Wright. These assert that there are real constants and such that

are prime for any natural number in the first formula, and any number of exponents in the second formula. Here represents the floor function, the largest integer less than or equal to the number in question. However, these are not useful for generating primes, as the primes must be generated first in order to compute the values of or

Open questions

Many conjectures revolving about primes have been posed. Often having an elementary formulation, many of these conjectures have withstood proof for decades: all four of Landau's problems from 1912 are still unsolved. One of them is Goldbach's conjecture, which asserts that every even integer greater than 2 can be written as a sum of two primes. As of 2014, this conjecture has been verified for all numbers up to Weaker statements than this have been proven, for example, Vinogradov's theorem says that every sufficiently large odd integer can be written as a sum of three primes. Chen's theorem says that every sufficiently large even number can be expressed as the sum of a prime and a semiprime (the product of two primes). Also, any even integer greater than 10 can be written as the sum of six primes. The branch of number theory studying such questions is called additive number theory.

Another type of problem concerns prime gaps, the differences between consecutive primes. The existence of arbitrarily large prime gaps can be seen by noting that the sequence consists of composite numbers, for any natural number However, large prime gaps occur much earlier than this argument shows. For example, the first prime gap of length 8 is between the primes 89 and 97, much smaller than It is conjectured that there are infinitely many twin primes, pairs of primes with difference 2; this is the twin prime conjecture. Polignac's conjecture states more generally that for every positive integer there are infinitely many pairs of consecutive primes that differ by Andrica's conjecture, Brocard's conjecture, Legendre's conjecture, and Oppermann's conjecture all suggest that the largest gaps between primes from to should be at most approximately a result that is known to follow from the Riemann hypothesis, while the much stronger Cramér conjecture sets the largest gap size at Prime gaps can be generalized to prime -tuples, patterns in the differences among more than two prime numbers. Their infinitude and density are the subject of the first Hardy–Littlewood conjecture, which can be motivated by the heuristic that the prime numbers behave similarly to a random sequence of numbers with density given by the prime number theorem.

Analytic properties

Analytic number theory studies number theory through the lens of continuous functions, limits, infinite series, and the related mathematics of the infinite and infinitesimal.

This area of study began with Leonhard Euler and his first major result, the solution to the Basel problem. The problem asked for the value of the infinite sum which today can be recognized as the value of the Riemann zeta function. This function is closely connected to the prime numbers and to one of the most significant unsolved problems in mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis. Euler showed that . The reciprocal of this number, , is the limiting probability that two random numbers selected uniformly from a large range are relatively prime (have no factors in common).

The distribution of primes in the large, such as the question how many primes are smaller than a given, large threshold, is described by the prime number theorem, but no efficient formula for the -th prime is known. Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions, in its basic form, asserts that linear polynomials

with relatively prime integers and take infinitely many prime values. Stronger forms of the theorem state that the sum of the reciprocals of these prime values diverges, and that different linear polynomials with the same have approximately the same proportions of primes. Although conjectures have been formulated about the proportions of primes in higher-degree polynomials, they remain unproven, and it is unknown whether there exists a quadratic polynomial that (for integer arguments) is prime infinitely often.

Analytical proof of Euclid's theorem

Euler's proof that there are infinitely many primes considers the sums of reciprocals of primes,

Euler showed that, for any arbitrary real number , there exists a prime for which this sum is bigger than . This shows that there are infinitely many primes, because if there were finitely many primes the sum would reach its maximum value at the biggest prime rather than growing past every . The growth rate of this sum is described more precisely by Mertens' second theorem. For comparison, the sum

does not grow to infinity as goes to infinity (see the Basel problem). In this sense, prime numbers occur more often than squares of natural numbers, although both sets are infinite. Brun's theorem states that the sum of the reciprocals of twin primes,

is finite. Because of Brun's theorem, it is not possible to use Euler's method to solve the twin prime conjecture, that there exist infinitely many twin primes.

Number of primes below a given bound

The prime-counting function is defined as the number of primes not greater than . For example, , since there are five primes less than or equal to 11. Methods such as the Meissel–Lehmer algorithm can compute exact values of faster than it would be possible to list each prime up to . The prime number theorem states that is asymptotic to , which is denoted as

and means that the ratio of to the right-hand fraction approaches 1 as grows to infinity. This implies that the likelihood that a randomly chosen number less than is prime is (approximately) inversely proportional to the number of digits in . It also implies that the th prime number is proportional to and therefore that the average size of a prime gap is proportional to . A more accurate estimate for is given by the offset logarithmic integral

Arithmetic progressions

An arithmetic progression is a finite or infinite sequence of numbers such that consecutive numbers in the sequence all have the same difference. This difference is called the modulus of the progression. For example,

- 3, 12, 21, 30, 39, ...,

is an infinite arithmetic progression with modulus 9. In an arithmetic progression, all the numbers have the same remainder when divided by the modulus; in this example, the remainder is 3. Because both the modulus 9 and the remainder 3 are multiples of 3, so is every element in the sequence. Therefore, this progression contains only one prime number, 3 itself. In general, the infinite progression

can have more than one prime only when its remainder and modulus are relatively prime. If they are relatively prime, Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions asserts that the progression contains infinitely many primes.

The Green–Tao theorem shows that there are arbitrarily long finite arithmetic progressions consisting only of primes.

Prime values of quadratic polynomials

Euler noted that the function

yields prime numbers for , although composite numbers appear among its later values. The search for an explanation for this phenomenon led to the deep algebraic number theory of Heegner numbers and the class number problem. The Hardy-Littlewood conjecture F predicts the density of primes among the values of quadratic polynomials with integer coefficients in terms of the logarithmic integral and the polynomial coefficients. No quadratic polynomial has been proven to take infinitely many prime values.

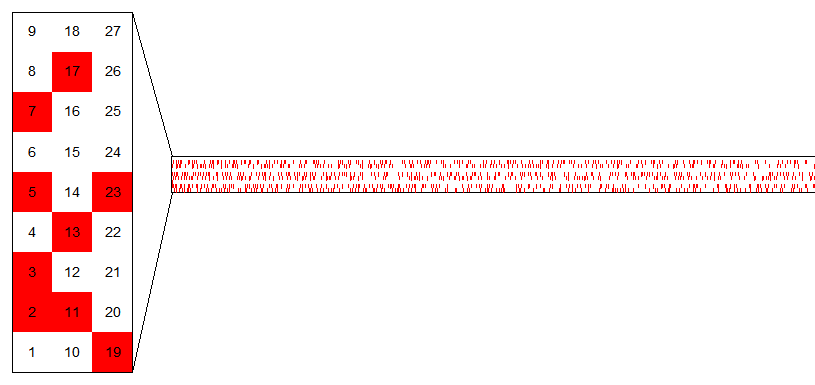

The Ulam spiral arranges the natural numbers in a two-dimensional grid, spiraling in concentric squares surrounding the origin with the prime numbers highlighted. Visually, the primes appear to cluster on certain diagonals and not others, suggesting that some quadratic polynomials take prime values more often than others.

Zeta function and the Riemann hypothesis

One of the most famous unsolved questions in mathematics, dating from 1859, and one of the Millennium Prize Problems, is the Riemann hypothesis, which asks where the zeros of the Riemann zeta function are located. This function is an analytic function on the complex numbers. For complex numbers with real part greater than one it equals both an infinite sum over all integers, and an infinite product over the prime numbers,

This equality between a sum and a product, discovered by Euler, is called an Euler product. The Euler product can be derived from the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, and shows the close connection between the zeta function and the prime numbers. It leads to another proof that there are infinitely many primes: if there were only finitely many, then the sum-product equality would also be valid at , but the sum would diverge (it is the harmonic series ) while the product would be finite, a contradiction.

The Riemann hypothesis states that the zeros of the zeta-function are all either negative even numbers, or complex numbers with real part equal to 1/2. The original proof of the prime number theorem was based on a weak form of this hypothesis, that there are no zeros with real part equal to 1, although other more elementary proofs have been found. The prime-counting function can be expressed by Riemann's explicit formula as a sum in which each term comes from one of the zeros of the zeta function; the main term of this sum is the logarithmic integral, and the remaining terms cause the sum to fluctuate above and below the main term. In this sense, the zeros control how regularly the prime numbers are distributed. If the Riemann hypothesis is true, these fluctuations will be small, and the asymptotic distribution of primes given by the prime number theorem will also hold over much shorter intervals (of length about the square root of for intervals near a number ).

Abstract algebra

Modular arithmetic and finite fields

Modular arithmetic modifies usual arithmetic by only using the numbers , for a natural number called the modulus. Any other natural number can be mapped into this system by replacing it by its remainder after division by . Modular sums, differences and products are calculated by performing the same replacement by the remainder on the result of the usual sum, difference, or product of integers. Equality of integers corresponds to congruence in modular arithmetic: and are congruent (written mod ) when they have the same remainder after division by . However, in this system of numbers, division by all nonzero numbers is possible if and only if the modulus is prime. For instance, with the prime number as modulus, division by is possible: , because clearing denominators by multiplying both sides by gives the valid formula . However, with the composite modulus , division by is impossible. There is no valid solution to : clearing denominators by multiplying by causes the left-hand side to become while the right-hand side becomes either or . In the terminology of abstract algebra, the ability to perform division means that modular arithmetic modulo a prime number forms a field or, more specifically, a finite field, while other moduli only give a ring but not a field.

Several theorems about primes can be formulated using modular arithmetic. For instance, Fermat's little theorem states that if (mod ), then (mod ). Summing this over all choices of gives the equation

valid whenever is prime. Giuga's conjecture says that this equation is also a sufficient condition for to be prime. Wilson's theorem says that an integer is prime if and only if the factorial is congruent to mod . For a composite number this cannot hold, since one of its factors divides both n and , and so is impossible.

p-adic numbers

The -adic order of an integer is the number of copies of in the prime factorization of . The same concept can be extended from integers to rational numbers by defining the -adic order of a fraction to be . The -adic absolute value of any rational number is then defined as . Multiplying an integer by its -adic absolute value cancels out the factors of in its factorization, leaving only the other primes. Just as the distance between two real numbers can be measured by the absolute value of their distance, the distance between two rational numbers can be measured by their -adic distance, the -adic absolute value of their difference. For this definition of distance, two numbers are close together (they have a small distance) when their difference is divisible by a high power of . In the same way that the real numbers can be formed from the rational numbers and their distances, by adding extra limiting values to form a complete field, the rational numbers with the -adic distance can be extended to a different complete field, the -adic numbers.

This picture of an order, absolute value, and complete field derived from them can be generalized to algebraic number fields and their valuations (certain mappings from the multiplicative group of the field to a totally ordered additive group, also called orders), absolute values (certain multiplicative mappings from the field to the real numbers, also called norms), and places (extensions to complete fields in which the given field is a dense set, also called completions). The extension from the rational numbers to the real numbers, for instance, is a place in which the distance between numbers is the usual absolute value of their difference. The corresponding mapping to an additive group would be the logarithm of the absolute value, although this does not meet all the requirements of a valuation. According to Ostrowski's theorem, up to a natural notion of equivalence, the real numbers and -adic numbers, with their orders and absolute values, are the only valuations, absolute values, and places on the rational numbers. The local-global principle allows certain problems over the rational numbers to be solved by piecing together solutions from each of their places, again underlining the importance of primes to number theory.

Prime elements in rings

A commutative ring is an algebraic structure where addition, subtraction and multiplication are defined. The integers are a ring, and the prime numbers in the integers have been generalized to rings in two different ways, prime elements and irreducible elements. An element of a ring is called prime if it is nonzero, has no multiplicative inverse (that is, it is not a unit), and satisfies the following requirement: whenever divides the product of two elements of , it also divides at least one of or . An element is irreducible if it is neither a unit nor the product of two other non-unit elements. In the ring of integers, the prime and irreducible elements form the same set,

In an arbitrary ring, all prime elements are irreducible. The converse does not hold in general, but does hold for unique factorization domains.

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic continues to hold (by definition) in unique factorization domains. An example of such a domain is the Gaussian integers , the ring of complex numbers of the form where denotes the imaginary unit and and are arbitrary integers. Its prime elements are known as Gaussian primes. Not every number that is prime among the integers remains prime in the Gaussian integers; for instance, the number 2 can be written as a product of the two Gaussian primes and . Rational primes (the prime elements in the integers) congruent to 3 mod 4 are Gaussian primes, but rational primes congruent to 1 mod 4 are not. This is a consequence of Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares, which states that an odd prime is expressible as the sum of two squares, , and therefore factorable as , exactly when is 1 mod 4.

Prime ideals

Not every ring is a unique factorization domain. For instance, in the ring of numbers (for integers and ) the number has two factorizations , where neither of the four factors can be reduced any further, so it does not have a unique factorization. In order to extend unique factorization to a larger class of rings, the notion of a number can be replaced with that of an ideal, a subset of the elements of a ring that contains all sums of pairs of its elements, and all products of its elements with ring elements. Prime ideals, which generalize prime elements in the sense that the principal ideal generated by a prime element is a prime ideal, are an important tool and object of study in commutative algebra, algebraic number theory and algebraic geometry. The prime ideals of the ring of integers are the ideals (0), (2), (3), (5), (7), (11), ... The fundamental theorem of arithmetic generalizes to the Lasker–Noether theorem, which expresses every ideal in a Noetherian commutative ring as an intersection of primary ideals, which are the appropriate generalizations of prime powers.

The spectrum of a ring is a geometric space whose points are the prime ideals of the ring. Arithmetic geometry also benefits from this notion, and many concepts exist in both geometry and number theory. For example, factorization or ramification of prime ideals when lifted to an extension field, a basic problem of algebraic number theory, bears some resemblance with ramification in geometry. These concepts can even assist with in number-theoretic questions solely concerned with integers. For example, prime ideals in the ring of integers of quadratic number fields can be used in proving quadratic reciprocity, a statement that concerns the existence of square roots modulo integer prime numbers. Early attempts to prove Fermat's Last Theorem led to Kummer's introduction of regular primes, integer prime numbers connected with the failure of unique factorization in the cyclotomic integers. The question of how many integer prime numbers factor into a product of multiple prime ideals in an algebraic number field is addressed by Chebotarev's density theorem, which (when applied to the cyclotomic integers) has Dirichlet's theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions as a special case.

Group theory

In the theory of finite groups the Sylow theorems imply that, if a power of a prime number divides the order of a group, then the group has a subgroup of order . By Lagrange's theorem, any group of prime order is a cyclic group, and by Burnside's theorem any group whose order is divisible by only two primes is solvable.

Computational methods

For a long time, number theory in general, and the study of prime numbers in particular, was seen as the canonical example of pure mathematics, with no applications outside of mathematics other than the use of prime numbered gear teeth to distribute wear evenly. In particular, number theorists such as British mathematician G. H. Hardy prided themselves on doing work that had absolutely no military significance.

This vision of the purity of number theory was shattered in the 1970s, when it was publicly announced that prime numbers could be used as the basis for the creation of public-key cryptography algorithms. These applications have led to significant study of algorithms for computing with prime numbers, and in particular of primality testing, methods for determining whether a given number is prime. The most basic primality testing routine, trial division, is too slow to be useful for large numbers. One group of modern primality tests is applicable to arbitrary numbers, while more efficient tests are available for numbers of special types. Most primality tests only tell whether their argument is prime or not. Routines that also provide a prime factor of composite arguments (or all of its prime factors) are called factorization algorithms. Prime numbers are also used in computing for checksums, hash tables, and pseudorandom number generators.

Trial division

The most basic method of checking the primality of a given integer is called trial division. This method divides by each integer from 2 up to the square root of . Any such integer dividing evenly establishes as composite; otherwise it is prime. Integers larger than the square root do not need to be checked because, whenever , one of the two factors and is less than or equal to the square root of . Another optimization is to check only primes as factors in this range. For instance, to check whether 37 is prime, this method divides it by the primes in the range from 2 to , which are 2, 3, and 5. Each division produces a nonzero remainder, so 37 is indeed prime.

Although this method is simple to describe, it is impractical for testing the primality of large integers, because the number of tests that it performs grows exponentially as a function of the number of digits of these integers. However, trial division is still used, with a smaller limit than the square root on the divisor size, to quickly discover composite numbers with small factors, before using more complicated methods on the numbers that pass this filter.

Sieves

Before computers, mathematical tables listing all of the primes or prime factorizations up to a given limit were commonly printed. The oldest method for generating a list of primes is called the sieve of Eratosthenes. The animation shows an optimized variant of this method. Another more asymptotically efficient sieving method for the same problem is the sieve of Atkin. In advanced mathematics, sieve theory applies similar methods to other problems.

Primality testing versus primality proving

Some of the fastest modern tests for whether an arbitrary given number is prime are probabilistic (or Monte Carlo) algorithms, meaning that they have a small random chance of producing an incorrect answer. For instance the Solovay–Strassen primality test on a given number chooses a number randomly from through and uses modular exponentiation to check whether is divisible by . If so, it answers yes and otherwise it answers no. If really is prime, it will always answer yes, but if is composite then it answers yes with probability at most 1/2 and no with probability at least 1/2. If this test is repeated times on the same number, the probability that a composite number could pass the test every time is at most . Because this decreases exponentially with the number of tests, it provides high confidence (although not certainty) that a number that passes the repeated test is prime. On the other hand, if the test ever fails, then the number is certainly composite. A composite number that passes such a test is called a pseudoprime.

In contrast, some other algorithms guarantee that their answer will always be correct: primes will always be determined to be prime and composites will always be determined to be composite. For instance, this is true of trial division. The algorithms with guaranteed-correct output include both deterministic (non-random) algorithms, such as the AKS primality test, and randomized Las Vegas algorithms where the random choices made by the algorithm do not affect its final answer, such as some variations of elliptic curve primality proving. When the elliptic curve method concludes that a number is prime, it provides primality certificate that can be verified quickly. The elliptic curve primality test is the fastest in practice of the guaranteed-correct primality tests, but its runtime analysis is based on heuristic arguments rather than rigorous proofs. The AKS primality test has mathematically proven time complexity, but is slower than elliptic curve primality proving in practice. These methods can be used to generate large random prime numbers, by generating and testing random numbers until finding one that is prime; when doing this, a faster probabilistic test can quickly eliminate most composite numbers before a guaranteed-correct algorithm is used to verify that the remaining numbers are prime.

The following table lists some of these tests. Their running time is given in terms of , the number to be tested and, for probabilistic algorithms, the number of tests performed. Moreover, is an arbitrarily small positive number, and log is the logarithm to an unspecified base. The big O notation means that each time bound should be multiplied by a constant factor to convert it from dimensionless units to units of time; this factor depends on implementation details such as the type of computer used to run the algorithm, but not on the input parameters and .

| Test | Developed in | Type | Running time | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKS primality test | 2002 | deterministic |

|

| |

| Elliptic curve primality proving | 1986 | Las Vegas | heuristically |

|

|

| Baillie–PSW primality test | 1980 | Monte Carlo |

|

| |

| Miller–Rabin primality test | 1980 | Monte Carlo | error probability |

| |

| Solovay–Strassen primality test | 1977 | Monte Carlo | error probability |

|

Special-purpose algorithms and the largest known prime

In addition to the aforementioned tests that apply to any natural number, some numbers of a special form can be tested for primality more quickly. For example, the Lucas–Lehmer primality test can determine whether a Mersenne number (one less than a power of two) is prime, deterministically, in the same time as a single iteration of the Miller–Rabin test. This is why since 1992 (as of December 2018) the largest known prime has always been a Mersenne prime. It is conjectured that there are infinitely many Mersenne primes.

The following table gives the largest known primes of various types. Some of these primes have been found using distributed computing. In 2009, the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search project was awarded a US$100,000 prize for first discovering a prime with at least 10 million digits. The Electronic Frontier Foundation also offers $150,000 and $250,000 for primes with at least 100 million digits and 1 billion digits, respectively.

| Type | Prime | Number of decimal digits | Date | Found by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mersenne prime | 282,589,933 − 1 | 24,862,048 | December 7, 2018 | Patrick Laroche, Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search |

| Proth prime | 10,223 × 231,172,165 + 1 | 9,383,761 | October 31, 2016 | Péter Szabolcs, PrimeGrid |

| factorial prime | 208,003! − 1 | 1,015,843 | July 2016 | Sou Fukui |

| primorial prime[e] | 1,098,133# − 1 | 476,311 | March 2012 | James P. Burt, PrimeGrid |

| twin primes | 2,996,863,034,895 × 21,290,000 ± 1 | 388,342 | September 2016 | Tom Greer, PrimeGrid |

Integer factorization

Given a composite integer , the task of providing one (or all) prime factors is referred to as factorization of . It is significantly more difficult than primality testing, and although many factorization algorithms are known, they are slower than the fastest primality testing methods. Trial division and Pollard's rho algorithm can be used to find very small factors of , and elliptic curve factorization can be effective when has factors of moderate size. Methods suitable for arbitrary large numbers that do not depend on the size of its factors include the quadratic sieve and general number field sieve. As with primality testing, there are also factorization algorithms that require their input to have a special form, including the special number field sieve. As of December 2019 the largest number known to have been factored by a general-purpose algorithm is RSA-240, which has 240 decimal digits (795 bits) and is the product of two large primes.

Shor's algorithm can factor any integer in a polynomial number of steps on a quantum computer. However, current technology can only run this algorithm for very small numbers. As of October 2012 the largest number that has been factored by a quantum computer running Shor's algorithm is 21.

Other computational applications

Several public-key cryptography algorithms, such as RSA and the Diffie–Hellman key exchange, are based on large prime numbers (2048-bit primes are common). RSA relies on the assumption that it is much easier (that is, more efficient) to perform the multiplication of two (large) numbers and than to calculate and (assumed coprime) if only the product is known. The Diffie–Hellman key exchange relies on the fact that there are efficient algorithms for modular exponentiation (computing ), while the reverse operation (the discrete logarithm) is thought to be a hard problem.

Prime numbers are frequently used for hash tables. For instance the original method of Carter and Wegman for universal hashing was based on computing hash functions by choosing random linear functions modulo large prime numbers. Carter and Wegman generalized this method to -independent hashing by using higher-degree polynomials, again modulo large primes. As well as in the hash function, prime numbers are used for the hash table size in quadratic probing based hash tables to ensure that the probe sequence covers the whole table.

Some checksum methods are based on the mathematics of prime numbers. For instance the checksums used in International Standard Book Numbers are defined by taking the rest of the number modulo 11, a prime number. Because 11 is prime this method can detect both single-digit errors and transpositions of adjacent digits. Another checksum method, Adler-32, uses arithmetic modulo 65521, the largest prime number less than . Prime numbers are also used in pseudorandom number generators including linear congruential generators and the Mersenne Twister.

Other applications

Prime numbers are of central importance to number theory but also have many applications to other areas within mathematics, including abstract algebra and elementary geometry. For example, it is possible to place prime numbers of points in a two-dimensional grid so that no three are in a line, or so that every triangle formed by three of the points has large area. Another example is Eisenstein's criterion, a test for whether a polynomial is irreducible based on divisibility of its coefficients by a prime number and its square.

The concept of a prime number is so important that it has been generalized in different ways in various branches of mathematics. Generally, "prime" indicates minimality or indecomposability, in an appropriate sense. For example, the prime field of a given field is its smallest subfield that contains both 0 and 1. It is either the field of rational numbers or a finite field with a prime number of elements, whence the name. Often a second, additional meaning is intended by using the word prime, namely that any object can be, essentially uniquely, decomposed into its prime components. For example, in knot theory, a prime knot is a knot that is indecomposable in the sense that it cannot be written as the connected sum of two nontrivial knots. Any knot can be uniquely expressed as a connected sum of prime knots. The prime decomposition of 3-manifolds is another example of this type.

Beyond mathematics and computing, prime numbers have potential connections to quantum mechanics, and have been used metaphorically in the arts and literature. They have also been used in evolutionary biology to explain the life cycles of cicadas.

Constructible polygons and polygon partitions

Fermat primes are primes of the form

with a nonnegative integer. They are named after Pierre de Fermat, who conjectured that all such numbers are prime. The first five of these numbers – 3, 5, 17, 257, and 65,537 – are prime, but is composite and so are all other Fermat numbers that have been verified as of 2017. A regular -gon is constructible using straightedge and compass if and only if the odd prime factors of (if any) are distinct Fermat primes. Likewise, a regular -gon may be constructed using straightedge, compass, and an angle trisector if and only if the prime factors of are any number of copies of 2 or 3 together with a (possibly empty) set of distinct Pierpont primes, primes of the form .

It is possible to partition any convex polygon into smaller convex polygons of equal area and equal perimeter, when is a power of a prime number, but this is not known for other values of .

Quantum mechanics

Beginning with the work of Hugh Montgomery and Freeman Dyson in the 1970s, mathematicians and physicists have speculated that the zeros of the Riemann zeta function are connected to the energy levels of quantum systems. Prime numbers are also significant in quantum information science, thanks to mathematical structures such as mutually unbiased bases and symmetric informationally complete positive-operator-valued measures.

Biology

The evolutionary strategy used by cicadas of the genus Magicicada makes use of prime numbers. These insects spend most of their lives as grubs underground. They only pupate and then emerge from their burrows after 7, 13 or 17 years, at which point they fly about, breed, and then die after a few weeks at most. Biologists theorize that these prime-numbered breeding cycle lengths have evolved in order to prevent predators from synchronizing with these cycles. In contrast, the multi-year periods between flowering in bamboo plants are hypothesized to be smooth numbers, having only small prime numbers in their factorizations.

Arts and literature

Prime numbers have influenced many artists and writers. The French composer Olivier Messiaen used prime numbers to create ametrical music through "natural phenomena". In works such as La Nativité du Seigneur (1935) and Quatre études de rythme (1949–50), he simultaneously employs motifs with lengths given by different prime numbers to create unpredictable rhythms: the primes 41, 43, 47 and 53 appear in the third étude, "Neumes rythmiques". According to Messiaen this way of composing was "inspired by the movements of nature, movements of free and unequal durations".

In his science fiction novel Contact, scientist Carl Sagan suggested that prime factorization could be used as a means of establishing two-dimensional image planes in communications with aliens, an idea that he had first developed informally with American astronomer Frank Drake in 1975. In the novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon, the narrator arranges the sections of the story by consecutive prime numbers as a way to convey the mental state of its main character, a mathematically gifted teen with Asperger syndrome. Prime numbers are used as a metaphor for loneliness and isolation in the Paolo Giordano novel The Solitude of Prime Numbers, in which they are portrayed as "outsiders" among integers.

![\mathbb {Z} [i]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ffa94e9e2e6d9e5e5373d5fafb954b902743fde)