From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_monetary_theory

Modern monetary theory or modern money theory (MMT) is a heterodox macroeconomic theory that describes currency as a public monopoly and unemployment as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of the financial assets needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires. According to MMT, governments do not need to worry about accumulating debt since they can pay interest by printing money. MMT argues that the primary risk once the economy reaches full employment is inflation,

which acts as the only constraint on spending. MMT also argues that

inflation can be controlled by increasing taxes on everyone, to reduce

the spending capacity of the private sector.

MMT is opposed to the mainstream understanding of macroeconomic theory and has been criticized heavily by many mainstream economists. MMT is also strongly opposed by members of the Austrian school of economics, with Murray Rothbard stating that MMT practices are equivalent to "counterfeiting" and that government control of the money supply will inevitably lead to hyperinflation.

Principles

MMT's main tenets are that a government that issues its own fiat money:

- Can pay for goods, services, and financial assets without a need to first collect money in the form of taxes or debt issuance in advance of such purchases

- Cannot be forced to default on debt denominated in its own currency

- Is limited in its money creation and purchases only by inflation, which accelerates once the real resources (labour, capital and natural resources) of the economy are utilized at full employment

- Recommends strengthening automatic stabilisers to control demand-pull inflation, rather than relying upon discretionary tax changes

- Issues bonds as a monetary policy device, rather than as a funding device

The first four MMT tenets do not conflict with mainstream economics understanding of how money creation and inflation works. However, MMT economists disagree with mainstream economics about the fifth tenet: the impact of government deficits on interest rates.

History

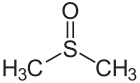

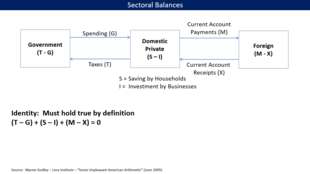

MMT synthesizes ideas from the state theory of money of Georg Friedrich Knapp (also known as chartalism) and the credit theory of money of Alfred Mitchell-Innes, the functional finance proposals of Abba Lerner, Hyman Minsky's views on the banking system and Wynne Godley's sectoral balances approach.

Knapp wrote in 1905 that "money is a creature of law", rather than a commodity. Knapp contrasted his state theory of money with the Gold Standard view of "metallism", where the value of a unit of currency depends on the quantity of precious metal it contains or for which it may be exchanged. He said that the state can create pure paper money and make it exchangeable by recognizing it as legal tender, with the criterion for the money of a state being "that which is accepted at the public pay offices".

The prevailing view of money was that it had evolved from systems of barter to become a medium of exchange because it represented a durable commodity which had some use value, but proponents of MMT such as Randall Wray and Mathew Forstater said that more general statements appearing to support a chartalist view of tax-driven paper money appear in the earlier writings of many classical economists, including Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, J. S. Mill, Karl Marx, and William Stanley Jevons.

Alfred Mitchell-Innes wrote in 1914 that money exists not as a medium of exchange but as a standard of deferred payment, with government money being debt the government may reclaim through taxation. Innes said:

Whenever a tax is imposed, each taxpayer becomes responsible for the redemption of a small part of the debt which the government has contracted by its issues of money, whether coins, certificates, notes, drafts on the treasury, or by whatever name this money is called. He has to acquire his portion of the debt from some holder of a coin or certificate or other form of government money, and present it to the Treasury in liquidation of his legal debt. He has to redeem or cancel that portion of the debt ... The redemption of government debt by taxation is the basic law of coinage and of any issue of government 'money' in whatever form.

— Alfred Mitchell-Innes, "The Credit Theory of Money", The Banking Law Journal

Knapp and "chartalism" are referenced by John Maynard Keynes in the opening pages of his 1930 Treatise on Money and appear to have influenced Keynesian ideas on the role of the state in the economy.

By 1947, when Abba Lerner wrote his article "Money as a Creature of the State", economists had largely abandoned the idea that the value of money was closely linked to gold. Lerner said that responsibility for avoiding inflation and depressions lay with the state because of its ability to create or tax away money.

Hyman Minsky seemed to favor a chartalist approach to understanding money creation in his Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, while Basil Moore, in his book Horizontalists and Verticalists, lists the differences between bank money and state money.

In 1996, Wynne Godley wrote an article on his sectoral balances approach, which MMT draws from.

Economists Warren Mosler, L. Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, Bill Mitchell and Pavlina R. Tcherneva are largely responsible for reviving the idea of chartalism as an explanation of money creation; Wray refers to this revived formulation as neo-chartalism.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell's book Free Money (1996) describes in layman's terms the essence of chartalism.

Pavlina R. Tcherneva has developed the first mathematical framework for MMT and has largely focused on developing the idea of the job guarantee.

Bill Mitchell, professor of economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CoFEE) at the University of Newcastle in Australia, coined the term 'modern monetary theory'. In their 2008 book Full Employment Abandoned, Mitchell and Joan Muysken use the term to explain monetary systems in which national governments have a monopoly on issuing fiat currency and where a floating exchange rate frees monetary policy from the need to protect foreign exchange reserves.

Some contemporary proponents, such as Wray, place MMT within post-Keynesian economics, while MMT has been proposed as an alternative or complementary theory to monetary circuit theory, both being forms of endogenous money, i.e., money created within the economy, as by government deficit spending or bank lending, rather than from outside, perhaps with gold. In the complementary view, MMT explains the "vertical" (government-to-private and vice versa) interactions, while circuit theory is a model of the "horizontal" (private-to-private) interactions.

By 2013, MMT had attracted a popular following through academic blogs and other websites.

In 2019, MMT became a major topic of debate after U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said in January that the theory should be a larger part of the conversation. In February 2019, Macroeconomics became the first academic textbook based on the theory, published by Bill Mitchell, Randall Wray, and Martin Watts. MMT became increasingly used by chief economists and Wall Street executives for economic forecasts and investment strategies. The theory was also intensely debated by lawmakers in Japan, which was planning to raise taxes after years of deficit spending.

In June 2020, Stephanie Kelton's MMT book The Deficit Myth became a New York Times bestseller.

In 2020 the Sri Lankan Central Bank, under the governor W. D. Lakshman, cited MMT as a justification for adopting unconventional monetary policy, which was continued by Ajith Nivard Cabraal. This has been heavily criticized and widely cited as causing accelerating inflation and exacerbating the Sri Lankan economic crisis. MMT scholars Stephanie Kelton and Fadhel Kaboub maintain that the Sri Lankan government's fiscal and monetary policy bore little resemblance to the recommendations of MMT economists.

Theoretical approach

In sovereign financial systems, banks can create money, but these "horizontal" transactions do not increase net financial assets because assets are offset by liabilities. According to MMT advocates, "The balance sheet of the government does not include any domestic monetary instrument on its asset side; it owns no money. All monetary instruments issued by the government are on its liability side and are created and destroyed with spending and taxing or bond offerings." In MMT, "vertical money" enters circulation through government spending. Taxation and its legal tender enable power to discharge debt and establish fiat money as currency, giving it value by creating demand for it in the form of a private tax obligation. In addition, fines, fees, and licenses create demand for the currency. This currency can be issued by the domestic government or by using a foreign, accepted currency. An ongoing tax obligation, in concert with private confidence and acceptance of the currency, underpins the value of the currency. Because the government can issue its own currency at will, MMT maintains that the level of taxation relative to government spending (the government's deficit spending or budget surplus) is in reality a policy tool that regulates inflation and unemployment, and not a means of funding the government's activities by itself. The approach of MMT typically reverses theories of governmental austerity. The policy implications of the two are likewise typically opposed.

Vertical transactions

MMT labels a transaction between a government entity (public sector) and a non-government entity (private sector) as a "vertical transaction". The government sector includes the treasury and central bank. The non-government sector includes domestic and foreign private individuals and firms (including the private banking system) and foreign buyers and sellers of the currency.

Interaction between government and the banking sector

MMT is based on an account of the "operational realities" of interactions between the government and its central bank, and the commercial banking sector, with proponents like Scott Fullwiler arguing that understanding reserve accounting is critical to understanding monetary policy options.

A sovereign government typically has an operating account with the country's central bank. From this account, the government can spend and also receive taxes and other inflows. Each commercial bank also has an account with the central bank, by means of which it manages its reserves (that is, money for clearing and settling interbank transactions).

When a government spends money, its central bank debits its Treasury's operating account and credits the reserve accounts of the commercial banks. The commercial bank of the final recipient will then credit up this recipient's deposit account by issuing bank money. This spending increases the total reserve deposits in the commercial bank sector. Taxation works in reverse: taxpayers have their bank deposit accounts debited, along with their bank's reserve account being debited to pay the government; thus, deposits in the commercial banking sector fall.

Government bonds and interest rate maintenance

Virtually all central banks set an interest rate target, and most now establish administered rates to anchor the short-term overnight interest rate at their target. These administered rates include interest paid directly on reserve balances held by commercial banks, a discount rate charged to banks for borrowing reserves directly from the central bank, and an Overnight Reverse Repurchase (ON RRP) facility rate paid to banks for temporarily forgoing reserves in exchange for Treasury securities. The latter facility is a type of open market operation to help ensure interest rates remain at a target level. According to MMT, the issuing of government bonds is best understood as an operation to offset government spending rather than a requirement to finance it.

In most countries, commercial banks' reserve accounts with the central bank must have a positive balance at the end of every day; in some countries, the amount is specifically set as a proportion of the liabilities a bank has, i.e., its customer deposits. This is known as a reserve requirement. At the end of every day, a commercial bank will have to examine the status of their reserve accounts. Those that are in deficit have the option of borrowing the required funds from the Central Bank, where they may be charged a lending rate (sometimes known as a discount window or discount rate) on the amount they borrow. On the other hand, the banks that have excess reserves can simply leave them with the central bank and earn a support rate from the central bank. Some countries, such as Japan, have a support rate of zero.

Banks with more reserves than they need will be willing to lend to banks with a reserve shortage on the interbank lending market. The surplus banks will want to earn a higher rate than the support rate that the central bank pays on reserves; whereas the deficit banks will want to pay a lower interest rate than the discount rate the central bank charges for borrowing. Thus, they will lend to each other until each bank has reached their reserve requirement. In a balanced system, where there are just enough total reserves for all the banks to meet requirements, the short-term interbank lending rate will be in between the support rate and the discount rate.

Under an MMT framework where government spending injects new reserves into the commercial banking system, and taxes withdraw them from the banking system, government activity would have an instant effect on interbank lending. If on a particular day, the government spends more than it taxes, reserves have been added to the banking system (see vertical transactions). This action typically leads to a system-wide surplus of reserves, with competition between banks seeking to lend their excess reserves, forcing the short-term interest rate down to the support rate (or to zero if a support rate is not in place). At this point, banks will simply keep their reserve surplus with their central bank and earn the support rate.

The alternate case is where the government receives more taxes on a particular day than it spends. Then there may be a system-wide deficit of reserves. Consequently, surplus funds will be in demand on the interbank market, and thus the short-term interest rate will rise towards the discount rate. Thus, if the central bank wants to maintain a target interest rate somewhere between the support rate and the discount rate, it must manage the liquidity in the system to ensure that the correct amount of reserves is on-hand in the banking system.

Central banks manage liquidity by buying and selling government bonds on the open market. When excess reserves are in the banking system, the central bank sells bonds, removing reserves from the banking system, because private individuals pay for the bonds. When insufficient reserves are in the system, the central bank buys government bonds from the private sector, adding reserves to the banking system.

The central bank buys bonds by simply creating money – it is not financed in any way. It is a net injection of reserves into the banking system. If a central bank is to maintain a target interest rate, then it must buy and sell government bonds on the open market in order to maintain the correct amount of reserves in the system.

Horizontal transactions

MMT economists describe any transactions within the private sector as "horizontal" transactions, including the expansion of the broad money supply through the extension of credit by banks.

MMT economists regard the concept of the money multiplier, where a bank is completely constrained in lending through the deposits it holds and its capital requirement, as misleading. Rather than being a practical limitation on lending, the cost of borrowing funds from the interbank market (or the central bank) represents a profitability consideration when the private bank lends in excess of its reserve or capital requirements (see interaction between government and the banking sector). Effects on employment are used as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of the financial assets needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires.

According to MMT, bank credit should be regarded as a "leverage" of the monetary base and should not be regarded as increasing the net financial assets held by an economy: only the government or central bank is able to issue high-powered money with no corresponding liability. Stephanie Kelton said that bank money is generally accepted in settlement of debt and taxes because of state guarantees, but that state-issued high-powered money sits atop a "hierarchy of money".

Foreign sector

Imports and exports

MMT proponents such as Warren Mosler say that trade deficits are sustainable and beneficial to the standard of living in the short term. Imports are an economic benefit to the importing nation because they provide the nation with real goods. Exports, however, are an economic cost to the exporting nation because it is losing real goods that it could have consumed. Currency transferred to foreign ownership, however, represents a future claim over goods of that nation.

Cheap imports may also cause the failure of local firms providing similar goods at higher prices, and hence unemployment, but MMT proponents label that consideration as a subjective value-based one, rather than an economic-based one: It is up to a nation to decide whether it values the benefit of cheaper imports more than it values employment in a particular industry. Similarly a nation overly dependent on imports may face a supply shock if the exchange rate drops significantly, though central banks can and do trade on foreign exchange markets to avoid shocks to the exchange rate.

Foreign sector and government

MMT says that as long as demand exists for the issuer's currency, whether the bond holder is foreign or not, governments can never be insolvent when the debt obligations are in their own currency; this is because the government is not constrained in creating its own fiat currency (although the bond holder may affect the exchange rate by converting to local currency).

MMT does agree with mainstream economics that debt in a foreign currency is a fiscal risk to governments, because the indebted government cannot create foreign currency. In this case, the only way the government can repay its foreign debt is to ensure that its currency is continually in high demand by foreigners over the period that it wishes to repay its debt; an exchange rate collapse would potentially multiply the debt many times over asymptotically, making it impossible to repay. In that case, the government can default, or attempt to shift to an export-led strategy or raise interest rates to attract foreign investment in the currency. Either one negatively affects the economy.

Policy implications

Economist Stephanie Kelton explained several points made by MMT in March 2019:

- Under MMT, fiscal policy (i.e., government taxing and spending decisions) is the primary means of achieving full employment, establishing the budget deficit at the level necessary to reach that goal. In mainstream economics, monetary policy (i.e., Central Bank adjustment of interest rates and its balance sheet) is the primary mechanism, assuming there is some interest rate low enough to achieve full employment. Kelton said that "cutting interest rates is ineffective in a slump" because businesses, expecting weak profits and few customers, will not invest even at very low interest rates.

- Government interest expenses are proportional to interest rates, so raising rates is a form of stimulus (it increases the budget deficit and injects money into the private sector, other things being equal); cutting rates is a form of austerity.

- Achieving full employment can be administered via a centrally-funded job guarantee, which acts as an automatic stabilizer. When private sector jobs are plentiful, the government spending on guaranteed jobs is lower, and vice versa.

- Under MMT, expansionary fiscal policy, i.e., money creation to fund purchases, can increase bank reserves, which can lower interest rates. In mainstream economics, expansionary fiscal policy, i.e., debt issuance and spending, can result in higher interest rates, crowding out economic activity.

Economist John T. Harvey explained several of the premises of MMT and their policy implications in March 2019:

- The private sector treats labor as a cost to be minimized, so it cannot be expected to achieve full employment without government creating jobs, too, such as through a job guarantee.

- The public sector's deficit is the private sector's surplus and vice versa, by accounting identity, which increased private sector debt during the Clinton-era budget surpluses.

- Creating money activates idle resources, mainly labor. Not doing so is immoral.

- Demand can be insensitive to interest rate changes, so a key mainstream assumption, that lower interest rates lead to higher demand, is questionable.

- There is a "free lunch" in creating money to fund government expenditure to achieve full employment. Unemployment is a burden; full employment is not.

- Creating money alone does not cause inflation; spending it when the economy is at full employment can.

MMT says that "borrowing" is a misnomer when applied to a sovereign government's fiscal operations, because the government is merely accepting its own IOUs, and nobody can borrow back their own debt instruments. Sovereign government goes into debt by issuing its own liabilities that are financial wealth to the private sector. "Private debt is debt, but government debt is financial wealth to the private sector."

In this theory, sovereign government is not financially constrained in its ability to spend; the government can afford to buy anything that is for sale in currency that it issues; there may, however, be political constraints, like a debt ceiling law. The only constraint is that excessive spending by any sector of the economy, whether households, firms, or public, could cause inflationary pressures.

MMT economists advocate a government-funded job guarantee scheme to eliminate involuntary unemployment. Proponents say that this activity can be consistent with price stability because it targets unemployment directly rather than attempting to increase private sector job creation indirectly through a much larger economic stimulus, and maintains a "buffer stock" of labor that can readily switch to the private sector when jobs become available. A job guarantee program could also be considered an automatic stabilizer to the economy, expanding when private sector activity cools down and shrinking in size when private sector activity heats up.

MMT economists also say quantitative easing is unlikely to have the effects that its advocates hope for. Under MMT, QE – the purchasing of government debt by central banks – is simply an asset swap, exchanging interest-bearing dollars for non-interest-bearing dollars. The net result of this procedure is not to inject new investment into the real economy, but instead to drive up asset prices, shifting money from government bonds into other assets such as equities, which enhances economic inequality. The Bank of England's analysis of QE confirms that it has disproportionately benefited the wealthiest.

MMT economists say that inflation can be better controlled (than by setting interest rates) with new or increased taxes to remove extra money from the economy. These tax increases would be on everyone, not just billionaires, since the majority of spending is by average Americans.

Comparison of MMT with mainstream Keynesian economics

MMT can be compared and contrasted with mainstream Keynesian economics in a variety of ways:

| Topic | Mainstream Keynesian | MMT |

|---|---|---|

| Funding government spending | Advocates taxation and issuing bonds (debt) as preferred methods for funding government spending. | Emphasizes that government fund spending by crediting bank accounts. |

| Purpose of taxation | To pay down debt from central banks loaned to the government at interest, which is spent into the economy and the taxpayer needs to repay. | Primarily to drive up demand for currency. Secondary uses of taxation include lowering inflation, reducing income inequality, and discouraging bad behavior. |

| Achieving full employment | Main strategy uses monetary policy; central bank has "dual mandate" of maximum employment and stable prices, but these goals are not always compatible. For example, much higher interest rates used to reduce inflation also caused high unemployment in the early 1980s. | Main strategy uses fiscal policy; running a budget deficit large enough to achieve full employment through a job guarantee. |

| Inflation control | Driven by monetary policy; central bank sets interest rates consistent with a stable price level, sometimes setting a target inflation rate. | Driven by fiscal policy; government increases taxes on everyone to remove money from private sector. A job guarantee also provides a NAIBER, which acts as an inflation control mechanism. |

| Setting interest rates | Managed by central bank to achieve "dual mandate" of maximum employment and stable prices. | Emphasizes that an interest rate target is not a potent policy. The government may choose to maintain a zero interest-rate policy by not issuing public debt at all. |

| Budget deficit impact on interest rates | At full employment, higher budget deficit can crowd out investment. | Deficit spending can drive down interest rates, encouraging investment and thus "crowding in" economic activity. |

| Automatic stabilizers | Primary stabilizers are unemployment insurance and food stamps, which increase budget deficits in a downturn. | In addition to the other stabilizers, a job guarantee would increase deficits in a downturn. |

Criticism

A 2019 survey of leading economists by the University of Chicago Booth's Initiative on Global Markets showed a unanimous rejection of assertions attributed by the survey to MMT: "Countries that borrow in their own currency should not worry about government deficits because they can always create money to finance their debt" and "Countries that borrow in their own currency can finance as much real government spending as they want by creating money". Directly responding to the survey, MMT economist William K. Black said "MMT scholars do not make or support either claim." Multiple MMT academics regard the attribution of these claims as a smear.

The post-Keynesian economist Thomas Palley has stated that MMT is largely a restatement of elementary Keynesian economics, but prone to "over-simplistic analysis" and understating the risks of its policy implications. Palley has disagreed with proponents of MMT who have asserted that standard Keynesian analysis does not fully capture the accounting identities and financial restraints on a government that can issue its own money. He said that these insights are well captured by standard Keynesian stock-flow consistent IS-LM models, and have been well understood by Keynesian economists for decades. He claimed MMT "assumes away the problem of fiscal–monetary conflict" – that is, that the governmental body that creates the spending budget (e.g. the legislature) may refuse to cooperate with the governmental body that controls the money supply (e.g., the central bank). He stated the policies proposed by MMT proponents would cause serious financial instability in an open economy with flexible exchange rates, while using fixed exchange rates would restore hard financial constraints on the government and "undermines MMT's main claim about sovereign money freeing governments from standard market disciplines and financial constraints". Furthermore, Palley has asserted that MMT lacks a plausible theory of inflation, particularly in the context of full employment in the employer of last resort policy first proposed by Hyman Minsky and advocated by Bill Mitchell and other MMT theorists; of a lack of appreciation of the financial instability that could be caused by permanently zero interest rates; and of overstating the importance of government-created money. Palley concludes that MMT provides no new insights about monetary theory, while making unsubstantiated claims about macroeconomic policy, and that MMT has only received attention recently due to it being a "policy polemic for depressed times".

Marc Lavoie has said that whilst the neochartalist argument is "essentially correct", many of its counter-intuitive claims depend on a "confusing" and "fictitious" consolidation of government and central banking operations, which is what Palley calls "the problem of fiscal–monetary conflict".

New Keynesian economist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, Paul Krugman, asserted MMT goes too far in its support for government budget deficits, and ignores the inflationary implications of maintaining budget deficits when the economy is growing. Krugman accused MMT devotees as engaging in "calvinball" – a game from the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes in which the players change the rules at whim. Austrian School economist Robert P. Murphy stated that MMT is "dead wrong" and that "the MMT worldview doesn't live up to its promises". He said that MMT saying cutting government deficits erodes private saving is true "only for the portion of private saving that is not invested" and says that the national accounting identities used to explain this aspect of MMT could equally be used to support arguments that government deficits "crowd out" private sector investment.

The chartalist view of money itself, and the MMT emphasis on the importance of taxes in driving money, is also a source of criticism. In 2015, three MMT economists, Scott Fullwiler, Stephanie Kelton, and L. Randall Wray, addressed what they saw as the main criticisms being made.