Origin

The term is believed to have been coined by Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), an American social scientist. Veblen's contemporary, popular historian Charles A. Beard, provided this apt determinist image, "Technology marches in seven-league boots from one ruthless, revolutionary conquest to another, tearing down old factories and industries, flinging up new processes with terrifying rapidity." As to the meaning, it is described as the ascription of "powers" to machines that they do not have. Veblen, for instance, asserted that "the machine throws out anthropomorphic habits of thought." There is also the case of Karl Marx who expected that the construction of the railway in India would dissolve the caste system. The general idea, according to Robert Heilbroner, is that technology, by way of its machines, can cause historical change by changing the material conditions of human existence.

One of the most radical technological determinists was Clarence Ayres, who was a follower of Veblen's theory in the 20th century. Ayres is best known for developing economic philosophies, but he also worked closely with Veblen who coined the technological determinism theory. He often talked about the struggle between technology and ceremonial structure. One of his most notable theories involved the concept of "technological drag" where he explains technology as a self-generating process and institutions as ceremonial and this notion creates a technological over-determinism in the process.

Explanation

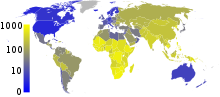

Technological determinism seeks to show technical developments, media, or technology as a whole, as the key mover in history and social change. It is a theory subscribed to by "hyperglobalists" who claim that as a consequence of the wide availability of technology, accelerated globalization is inevitable. Therefore, technological development and innovation become the principal motor of social, economic or political change.

Strict adherents to technological determinism do not believe the influence of technology differs based on how much a technology is or can be used. Instead of considering technology as part of a larger spectrum of human activity, technological determinism sees technology as the basis for all human activity.

Technological determinism has been summarized as 'The belief in technology as a key governing force in society ...' (Merritt Roe Smith). 'The idea that technological development determines social change ...' (Bruce Bimber). It changes the way people think and how they interact with others and can be described as '...a three-word logical proposition: "Technology determines history"' (Rosalind H. Williams) . It is, '... the belief that social progress is driven by technological innovation, which in turn follows an "inevitable" course.' This 'idea of progress' or 'doctrine of progress' is centralized around the idea that social problems can be solved by technological advancement, and this is the way that society moves forward. Technological determinists believe that "'You can't stop progress', implying that we are unable to control technology" (Lelia Green). This suggests that we are somewhat powerless and society allows technology to drive social changes because "societies fail to be aware of the alternatives to the values embedded in it [technology]" (Merritt Roe Smith).

Technological determinism has been defined as an approach that identifies technology, or technological advances, as the central causal element in processes of social change. As technology is stabilized, its design tends to dictate users' behaviors, consequently stating that "technological progress equals social progress." Key notions of this theory are separated into two parts, with the first being that the development of the technology itself may also be separate from social and political factors, arising from "the ways of inventors, engineers, and designers following an internal, technical logic that has nothing to do with social relationships". The second is that as technology is stabilized, its design tends to dictate users' behaviors, consequently resulting in social change.

As technology changes, the ways in which it is utilized and incorporated into the daily lives of individuals within a culture consequently affect the ways of living, highlighting how technology ultimately determines societal growth through its influence on relations and ways of living within a culture. To illustrate, "the invention of the wheel revolutionized human mobility, allowing humans to travel greater distances and carry greater loads with them". This technological advancement also leads to interactions between different cultural groups, advanced trade, etc, and thus impacts the size and relations both within and between different networks. Other examples include the invention of language, expanding modes of communication between individuals, the introduction of bookkeeping and written documentation, impacting the circulation of knowledge, and having streamlined effects on the socioeconomic and political systems as a whole. As Dusek (2006) notes, "culture and society cannot affect the direction of technology…[and] as technology develops and changes, the institutions in the rest of society change, as does the art and religion of a society." Thus, technological determinism dictates that technological advances and social relations are inevitably tied, with the change of either affecting the other by consequence of normalization.

This stance however ignores the social and cultural circumstances in which the technology was developed. Sociologist Claude Fischer (1992) characterized the most prominent forms of technological determinism as "billiard ball" approaches, in which technology is seen as an external force introduced into a social situation, producing a series of ricochet effects.

Rather than acknowledging that a society or culture interacts with and even shapes the technologies that are used, a technological determinist view holds that "the uses made of technology are largely determined by the structure of the technology itself, that is, that its functions follow from its form" (Neil Postman). However, this is not the sole view of TD following Smith and Marx's (1998) notion of "hard" determinism, which states that once a technology is introduced into a culture what follows is the inevitable development of that technology. In this view, the role of "agency (the power to affect change) is imputed on the technology itself, or some of its intrinsic attributes; thus the invention of technology leads to a situation of inescapable necessity."

The other view follows what Smith and Marx (1998) dictate as "soft" determinism, where the development of technology is also dependent on social context, affecting how it is adopted into a culture, "and, if the technology is adopted, the social context will have important effects on how the technology is used and thus on its ultimate impact".

For example, we could examine the spread of mass-produced knowledge through the role of the printing press in the Protestant Reformation. Because of the urgency from the protestant side to get the reform off the ground before the church could react, "early Lutheran leaders, led by Luther himself, wrote thousands of anti-papal pamphlets in the Reformation's first decades and these works spread rapidly through reprinting in various print shops throughout central Europe". As such the urgency of the socio-political context to utilize such technology in the beginning of its invention caused its fast adoption and normalization into European culture. We could view its uses in its popularization – for political propaganda purposes – in line with the continued traditions of newspapers in modern times, as well as newly adopted uses for other printed text, adapting to change in a social context such as an emphasis on leisurely activities such as reading. This follows the soft deterministic view because the technological invention – the printing press – was quickly adopted because of the socio-political context, and because of its fast integration into society, has impacted and continues to impact how society operates.

Hard and soft determinism

In examining determinism, hard determinism can be contrasted with soft determinism. A compatibilist says that it is possible for free will and determinism to exist in the world together, while an incompatibilist would say that they can not and there must be one or the other. Those who support determinism can be further divided.

Hard determinists would view technology as developing independent from social concerns. They would say that technology creates a set of powerful forces acting to regulate our social activity and its meaning. According to this view of determinism we organize ourselves to meet the needs of technology and the outcome of this organization is beyond our control or we do not have the freedom to make a choice regarding the outcome (autonomous technology). The 20th century French philosopher and social theorist Jacques Ellul could be said to be a hard determinist and proponent of autonomous technique (technology). In his 1954 work The Technological Society, Ellul essentially posits that technology, by virtue of its power through efficiency, determines which social aspects are best suited for its own development through a process of natural selection. A social system's values, morals, philosophy etc. that are most conducive to the advancement of technology allow that social system to enhance its power and spread at the expense of those social systems whose values, morals, philosophy etc. are less promoting of technology. While geography, climate, and other "natural" factors largely determined the parameters of social conditions for most of human history, technology has recently become the dominant objective factor (largely due to forces unleashed by the industrial revolution) and it has been the principal objective and determining factor.

Soft determinism, as the name suggests, is a more passive view of the way technology interacts with socio-political situations. Soft determinists still subscribe to the fact that technology is the guiding force in our evolution, but would maintain that we have a chance to make decisions regarding the outcomes of a situation. This is not to say that free will exists, but that the possibility for us to roll the dice and see what the outcome is exists. A slightly different variant of soft determinism is the 1922 technology-driven theory of social change proposed by William Fielding Ogburn, in which society must adjust to the consequences of major inventions, but often does so only after a period of cultural lag.

Technology as neutral

Individuals who consider technology as neutral see technology as neither good nor bad and what matters are the ways in which we use technology. An example of a neutral viewpoint is, "guns are neutral and its up to how we use them whether it would be 'good or bad'" (Green, 2001). Mackenzie and Wajcman believe that technology is neutral only if it's never been used before, or if no one knows what it is going to be used for (Green, 2001). In effect, guns would be classified as neutral if and only if society were none the wiser of their existence and functionality (Green, 2001). Obviously, such a society is non-existent and once becoming knowledgeable about technology, the society is drawn into a social progression where nothing is 'neutral about society' (Green). According to Lelia Green, if one believes technology is neutral, one would disregard the cultural and social conditions that technology has produced (Green, 2001). This view is also referred to as technological instrumentalism.

In what is often considered a definitive reflection on the topic, the historian Melvin Kranzberg famously wrote in the first of his six laws of technology: "Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral."

Criticism

Skepticism about technological determinism emerged alongside increased pessimism about techno-science in the mid-20th century, in particular around the use of nuclear energy in the production of nuclear weapons, Nazi human experimentation during World War II, and the problems of economic development in the Third World. As a direct consequence, desire for greater control of the course of development of technology gave rise to disenchantment with the model of technological determinism in academia.

Modern theorists of technology and society no longer consider technological determinism to be a very accurate view of the way in which we interact with technology, even though determinist assumptions and language fairly saturate the writings of many boosters of technology, the business pages of many popular magazines, and much reporting on technology. Instead, research in science and technology studies, social construction of technology and related fields have emphasised more nuanced views that resist easy causal formulations. They emphasise that "The relationship between technology and society cannot be reduced to a simplistic cause-and-effect formula. It is, rather, an 'intertwining'", whereby technology does not determine but "operates, and are operated upon in a complex social field" (Murphie and Potts).

T. Snyder approached the aspect of technological determinism in his concept: 'politics of inevitability'. A concept utilized by politicians in which society is promised the idea that the future will be only more of the present, this concept removes responsibility. This could be applied to free markets, the development of nation states and technological progress.

In his article "Subversive Rationalization: Technology, Power and Democracy with Technology," Andrew Feenberg argues that technological determinism is not a very well founded concept by illustrating that two of the founding theses of determinism are easily questionable and in doing so calls for what he calls democratic rationalization (Feenberg 210–212).

Prominent opposition to technologically determinist thinking has emerged within work on the social construction of technology (SCOT). SCOT research, such as that of Mackenzie and Wajcman (1997) argues that the path of innovation and its social consequences are strongly, if not entirely shaped by society itself through the influence of culture, politics, economic arrangements, regulatory mechanisms and the like. In its strongest form, verging on social determinism, "What matters is not the technology itself, but the social or economic system in which it is embedded" (Langdon Winner).

In his influential but contested (see Woolgar and Cooper, 1999) article "Do Artifacts Have Politics?", Langdon Winner illustrates not a form of determinism but the various sources of the politics of technologies. Those politics can stem from the intentions of the designer and the culture of the society in which a technology emerges or can stem from the technology itself, a "practical necessity" for it to function. For instance, New York City urban planner Robert Moses is purported to have built Long Island's parkway tunnels too low for buses to pass in order to keep minorities away from the island's beaches, an example of externally inscribed politics. On the other hand, an authoritarian command-and-control structure is a practical necessity of a nuclear power plant if radioactive waste is not to fall into the wrong hands. As such, Winner neither succumbs to technological determinism nor social determinism. The source of a technology's politics is determined only by carefully examining its features and history.

Although "The deterministic model of technology is widely propagated in society" (Sarah Miller), it has also been widely questioned by scholars. Lelia Green explains that, "When technology was perceived as being outside society, it made sense to talk about technology as neutral". Yet, this idea fails to take into account that culture is not fixed and society is dynamic. When "Technology is implicated in social processes, there is nothing neutral about society" (Lelia Green). This confirms one of the major problems with "technological determinism and the resulting denial of human responsibility for change. There is a loss of human involvement that shape technology and society" (Sarah Miller).

Another conflicting idea is that of technological somnambulism, a term coined by Winner in his essay "Technology as Forms of Life". Winner wonders whether or not we are simply sleepwalking through our existence with little concern or knowledge as to how we truly interact with technology. In this view, it is still possible for us to wake up and once again take control of the direction in which we are traveling (Winner 104). However, it requires society to adopt Ralph Schroeder's claim that, "users don't just passively consume technology, but actively transform it".

In opposition to technological determinism are those who subscribe to the belief of social determinism and postmodernism. Social determinists believe that social circumstances alone select which technologies are adopted, with the result that no technology can be considered "inevitable" solely on its own merits. Technology and culture are not neutral and when knowledge comes into the equation, technology becomes implicated in social processes. The knowledge of how to create, enhance, and use technology is socially bound knowledge. Postmodernists take another view, suggesting that what is right or wrong is dependent on circumstance. They believe technological change can have implications on the past, present and future. While they believe technological change is influenced by changes in government policy, society and culture, they consider the notion of change to be a paradox, since change is constant.

Media and cultural studies theorist Brian Winston, in response to technological determinism, developed a model for the emergence of new technologies which is centered on the Law of the suppression of radical potential. In two of his books – Technologies of Seeing: Photography, Cinematography and Television (1997) and Media Technology and Society (1998) – Winston applied this model to show how technologies evolve over time, and how their 'invention' is mediated and controlled by society and societal factors which suppress the radical potential of a given technology.

The stirrup

One continued argument for technological determinism is centered on the stirrup and its impact on the creation of feudalism in Europe in the late 8th century/early 9th century. Lynn White is credited with first drawing this parallel between feudalism and the stirrup in his book Medieval Technology and Social Change, which was published in 1962 and argued that as "it made possible mounted shock combat", the new form of war made the soldier that much more efficient in supporting feudal townships (White, 2). According to White, the superiority of the stirrup in combat was found in the mechanics of the lance charge: "The stirrup made possible- though it did not demand- a vastly more effective mode of attack: now the rider could lay his lance at rest, held between the upper arm and the body, and make at his foe, delivering the blow not with his muscles but with the combined weight of himself and his charging stallion (White, 2)." White draws from a large research base, particularly Heinrich Brunner's "Der Reiterdienst und die Anfänge des Lehnwesens" in substantiating his claim of the emergence of feudalism. In focusing on the evolution of warfare, particularly that of cavalry in connection with Charles Martel's "diversion of a considerable part of the Church's vast military riches...from infantry to cavalry", White draws from Brunner's research and identifies the stirrup as the underlying cause for such a shift in military division and the subsequent emergence of feudalism (White, 4). Under the new brand of warfare garnered from the stirrup, White implicitly argues in favor of technological determinism as the vehicle by which feudalism was created.

Though an accomplished work, White's Medieval Technology and Social Change has since come under heavy scrutiny and condemnation. The most volatile critics of White's argument at the time of its publication, P.H. Sawyer and R.H. Hilton, call the work as a whole "a misleading adventurist cast to old-fashioned platitudes with a chain of obscure and dubious deductions from scanty evidence about the progress of technology (Sawyer and Hilton, 90)." They further condemn his methods and, by association, the validity of technological determinism: "Had Mr. White been prepared to accept the view that the English and Norman methods of fighting were not so very different in the eleventh century, he would have made the weakness of his argument less obvious, but the fundamental failure would remain: the stirrup cannot alone explain the changes it made possible (Sawyer and Hilton, 91)." For Sawyer and Hilton, though the stirrup may be useful in the implementation of feudalism, it cannot be credited for the creation of feudalism alone.

Despite the scathing review of White's claims, the technological determinist aspect of the stirrup is still in debate. Alex Roland, author of "Once More into the Stirrups; Lynne White Jr, Medieval Technology and Social Change", provides an intermediary stance: not necessarily lauding White's claims, but providing a little defense against Sawyer and Hilton's allegations of gross intellectual negligence. Roland views White's focus on technology to be the most relevant and important aspect of Medieval Technology and Social Change rather than the particulars of its execution: "But can these many virtues, can this utility for historians of technology, outweigh the most fundamental standards of the profession? Can historians of technology continue to read and assign a book that is, in the words of a recent critic, "shot through with over-simplification, with a progression of false connexions between cause and effect, and with evidence presented selectively to fit with [White's] own pre-conceived ideas"? The answer, I think, is yes, at least a qualified yes (Roland, 574–575)." Objectively, Roland claims Medieval Technology and Social Change a variable success, at least as "Most of White's argument stands... the rest has sparked useful lines of research (Roland, 584)." This acceptance of technological determinism is ambiguous at best, neither fully supporting the theory at large nor denouncing it, rather placing the construct firmly in the realm of the theoretical. Roland neither views technological determinism as completely dominant over history nor completely absent as well; in accordance with the above criterion of technological determinist structure, would Roland be classified as a "soft determinist".

Notable technological determinists

Thomas L. Friedman, American journalist, columnist and author, admits to being a technological determinist in his book The World Is Flat.

Futurist Raymond Kurzweil's theories about a technological singularity follow a technologically deterministic view of history.

Some interpret Karl Marx as advocating technological determinism, with such statements as "The Handmill gives you society with the feudal lord: the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist" (The Poverty of Philosophy, 1847), but others argue that Marx was not a determinist.

Technological determinist Walter J. Ong reviews the societal transition from an oral culture to a written culture in his work Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (1982). He asserts that this particular development is attributable to the use of new technologies of literacy (particularly print and writing,) to communicate thoughts which could previously only be verbalized. He furthers this argument by claiming that writing is purely context dependent as it is a "secondary modelling system" (8). Reliant upon the earlier primary system of spoken language, writing manipulates the potential of language as it depends purely upon the visual sense to communicate the intended information. Furthermore, the rather stagnant technology of literacy distinctly limits the usage and influence of knowledge, it unquestionably effects the evolution of society. In fact, Ong asserts that "more than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness" (Ong 1982: 78).