Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that technological development can change the modes of production over time. This change in the mode of production inevitably encourages changes to a society's economic system.

Marx's lifetime collaborator, Friedrich Engels, coins the term "historical materialism" and describes it as "that view of the course of history which seeks the ultimate cause and the great moving power of all important historic events in the economic development of society, in the changes in the modes of production and exchange, in the consequent division of society into distinct classes, and in the struggles of these classes against one another."

Although Marx never brought together a formal or comprehensive description of historical materialism in one published work, his key ideas are woven into a variety of works from the 1840s onward. Since Marx's time, the theory has been modified and expanded. It now has many Marxist and non-Marxist variants.

Enlightenment views of history

Marx's view of history was shaped by his engagement with the intellectual and philosophical movement known as the Age of Enlightenment and the profound scientific, political, economic and social transformations that took place in Britain and other parts of Europe in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

The "spirit of liberty"

Enlightenment thinkers responded to the worldly transformations by promoting individual liberties and attacking religious dogmas and the divine right of kings. A group of thinkers including Hobbes (1588–1679), Montesquieu (1689–1755), Voltaire (1694–1778), Smith (1723–1790), Turgot (1727–1781) and Condorcet (1743–1794) explored new forms of inquiry, including empirical studies of human nature, history, economics and society. Some philosophers, for example, Vico (1668–1744), Herder (1744–1803) and Hegel (1770–1831), sought to uncover organizing principles of human history in underlying themes, meanings, and directions. For many Enlightenment philosophers, the power of ideas became the mainspring for understanding historical change and the rise and fall of civilizations. History was the gradual advance of the "spirit of liberty" or the growth of nationalism or democracy, rationality and law. This view of history remains popular to this day.

Materialism

Beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, materialism came to prominence in Western philosophy, especially in opposition to the Cartesian rationalism of philosophers such as Descartes. Notable philosophers expounding materialist views included Francis Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, and John Locke. They were followed by a series of materialists in France in the 18th century such as Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Claude Adrien Helvétius, and Baron d'Holbach. In the 19th century, the pre-Marxist communists Théodore Dézamy and Jules Gay adopted materialism in their historical analysis of society as well. Marx inherited his materialist philosophy from this Gassendi-Dezamy line of thinkers.

Marx 's ideas were also influenced by his reading of Young Hegelian writer Ludwig Feuerbach's 1833 work Geschichte der neuern Philosophie von Bacon von Verulam bis Benedict Spinoza which covered Gassendi's materialist philosophy as well as Gassendi's treatment on materialist Ancient Greek philosophers such as Epicurus, Leucippus, and Democritus.

Materialist conception of history

Inspired by Enlightenment thinkers, especially Condorcet, the utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) formulated his own materialist interpretation of history, similar to those later used in Marxism, analyzing historical epochs based on their level of technology and organization and dividing them between eras of slavery, serfdom, and finally wage labor. According to the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, the French writer Antoine Barnave was the first to develop the theory that economic forces were the driving factors in history.

Marx came to his commitment to a materialist analysis of society and political economy around 1844 and completed his works The Holy Family in 1845, The German Ideology or Leipzig Council in 1846, and The Poverty of Philosophy in 1847 along with Friedrich Engels.

'Great man' history

Marx rejected the enlightenment view that ideas alone were the driving force in society or that the underlying cause of change was guided by the actions of leaders in government or religion. The "great man" and occasionally "great woman" view of historical change was popularized by the 19th-century Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) who wrote "the history of the world is nothing but the biography of great men". According to Marx, this conception of history amounted to nothing more than a collection of "high-sounding dramas of princes and states".

Hegel's contribution to Marx's theory of history

While studying at the University of Berlin, Marx encountered the philosophy of Hegel (1770–1831) which had a profound and lasting influence on his thinking. One of Hegel's key critiques of enlightenment philosophy was that while thinkers were often able to describe what made societies from one epoch to the next different, they struggled to account for why they changed.

Hegel and historicism

Classical economists presented a model of civil society based on a universal and unchanging human nature. Hegel challenged this view and argued that human nature as well as the formulations of art, science and the institutions of the state and its codes, laws and norms were all defined by their history and could only be understood by examining their historical development. Hegel’s philosophical thought saw it as an expression of a specific culture rather than an eternal truth: "Philosophy is its own age comprehended in thought."

World spirit

In each society, humans were 'free by nature" but constrained by their "brutal recklessness of passion" and "untamed natural impulses" that led to injustice and violence. It was only through wider society and the state, which was expressed in each historical epoch, by a "spirit of the age", collective consciousness or geist, that "Freedom" could be realized. For Hegel, history was the working through of a process where humans become ever more conscious of the rational principles that govern social development.

Dialectics of change

Hegel's dialectical method presents the world as a complex totality where all aspects of society (familial, economic, scientific, governmental, etc.) are interconnected, mutually influential, and unable to be considered in isolation. According to Hegel, at any particular point in time, society is an amalgam of contesting forces – some promoting stability and others striving for change. It is not just external factors that bring about transformation but internal contradictions. The unceasing drive of this dynamic is played out by real people struggling to achieve their aims. The outcome is that ideas, institutions and bodies of society are reconfigured into new forms expressing new characteristics. At certain decisive moments in history, during periods of great conflict, the actions of "great historical men" can align with the "spirit of the age" to bring about a fundamental advance in freedom.

Algebra of revolution

The implication of Hegel's philosophy that every social order, no matter how powerful and secure, will eventually wither away was incendiary. These ideas were inspirational to Marx and the Young Hegelians who sought to develop a radical critique of the Prussian authorities and their failure to introduce constitutional change or reform social institutions. However, Hegel's contention that ideas or the "spirit of the age" drive history was mistaken in Marx's view. Hegel, wrote Marx, "fell into the illusion of conceiving the real as the product of thought..." Marx contended that the engine of history was to be found in a materialist understanding of society - the productive process and the way humans labored to meet their needs. Marx and Engels first set out their materialist conception of history in The German Ideology, written in 1845. The book is a lengthy polemic against Marx and Engels' fellow Young Hegelians and contemporaries Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, and Max Stirner.

Historical materialism

In the Marxian view, human history is like a river. From any given vantage point, a river looks much the same day after day. But actually it is constantly flowing and changing, crumbling its banks, widening and deepening its channel. The water seen one day is never the same as that seen the next. Some of it is constantly being evaporated and drawn up, to return as rain. From year to year these changes may be scarcely perceptible. But one day, when the banks are thoroughly weakened and the rains long and heavy, the river floods, bursts its banks, and may take a new course. This represents the dialectical part of Marx's famous theory of dialectical (or historical) materialism.

— Hubert Kay, Life, 1948

The production of life

Marx based his theory of history on the necessity of labor to ensure physical survival. In The German Ideology, Marx wrote that the first historical act, was the production of means to satisfy material needs and that labor is a "fundamental condition of all history, which today, as thousands of years ago, must daily and hourly be fulfilled merely in order to sustain human life". Human labor forms the materialist basis for society and is at the heart of Marx's account of history. Marx viewed labor throughout history, in all societies and in all modes of production, from the earliest paleolithic hunter gatherers through to feudal societies and to modern capitalist economies as an "everlasting Nature-imposed condition of human existence" that compels humans to join socially to produce their means of subsistence.

Forces and relations of production

Marx identified two mutually interdependent structures of humans interaction with nature and the process of producing their subsistence: the forces of production and relations of production.

Forces of production

The forces of production are everything that humans use to make the things that society needs. They include human labor and the raw materials, land, tools, instruments and knowledge required for production. The flint sharpened spears and harpoons developed by early humans in the late Paleolithic period are all forces of production. Over time, the forces of production tend to develop and expand as new skills, knowledge and technology (for example wooden scratch plows then heavier iron plows) are put to use to meet human needs. From one generation to the next, technical skills, evolving traditions of practice and mechanical innovations are reproduced and disseminated.

Relations of production

Marx extended this premise by asserting the importance of the fact that, in order to carry out production and exchange, people have to enter into very definite social relations, or more specifically, "relations of production". However, production does not get carried out in the abstract, or by entering into arbitrary or random relations chosen at will, but instead are determined by the development of the existing forces of production.

The relations of production are determined by the level and character of these productive forces present at any given time in history. In all societies, human beings collectively work on nature but, especially in class societies, do not do the same work. In such societies, there is a division of labor in which people not only carry out different kinds of labor but occupy different social positions on the basis of those differences. The most important such division is that between manual and intellectual labor whereby one class produces a given society's wealth while another is able to monopolize control of the means of production. In this way, both govern that society and live off of the wealth generated by the laboring classes.

Base and superstructure

Marx identified society's relations of production (arising on the basis of given productive forces) as the economic base of society. He also explained that on the foundation of the economic base, there arise certain political institutions, laws, customs, culture, etc., and ideas, ways of thinking, morality, etc. These constitute the political/ideological "superstructure" of society. This superstructure not only has its origin in the economic base, but its features also ultimately correspond to the character and development of that economic base, i.e. the way people organize society, its relations of production, and its mode of production. G.A. Cohen argues in Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence that a society's superstructure stabilizes or entrenches its economic structure, but that the economic base is primary and the superstructure secondary. That said, it is precisely because the superstructure strongly affects the base that the base selects that superstructure. As Charles Taylor wrote: "These two directions of influence are so far from being rivals that they are actually complementary. The functional explanation requires that the secondary factor tend to have a causal effect on the primary, for this dispositional fact is the key feature of the explanation." It is because the influences in the two directions are not symmetrical that it makes sense to speak of primary and secondary factors, even where one is giving a non-reductionist, "holistic" account of social interaction.

To summarize, history develops in accordance with the following observations:

- Social progress is driven by progress in the material, productive forces a society has at its disposal (technology, labour, capital goods and so on).

- Humans are inevitably involved in productive relations (roughly speaking, economic relationships or institutions), which constitute the most decisive social relations. These relations progress with the development of the productive forces. They are largely determined by the division of labor, which in turn tends to determine social class.

- Relations of production are both determined by the means and forces of production and set the conditions of their development. For example, capitalism tends to increase the rate at which the forces develop and stresses the accumulation of capital.

- The relations of production define the mode of production, e.g. the capitalist mode of production is characterized by the polarization of society into capitalists and workers.

- The superstructure—the cultural and institutional features of a society, its ideological materials—is ultimately an expression of the mode of production on which the society is founded.

- Every type of state is a powerful institution of the ruling class; the state is an instrument which one class uses to secure its rule and enforce its preferred relations of production and its exploitation onto society.

- State power is usually only transferred from one class to another by social and political upheaval.

- When a given relation of production no longer supports further progress in the productive forces, either further progress is strangled, or 'revolution' must occur.

- The actual historical process is not predetermined but depends on class struggle, especially the elevation of class consciousness and organization of the working class.

Key implications in the study and understanding of history

Many writers note that historical materialism represented a revolution in human thought, and a break from previous ways of understanding the underlying basis of change within various human societies. As Marx puts it, "a coherence arises in human history" because each generation inherits the productive forces developed previously and in turn further develops them before passing them on to the next generation. Further, this coherence increasingly involves more of humanity the more the productive forces develop and expand to bind people together in production and exchange.

This understanding counters the notion that human history is simply a series of accidents, either without any underlying cause or caused by supernatural beings or forces exerting their will on society. Historical materialism posits that history is made as a result of struggle between different social classes rooted in the underlying economic base. According to G. A. Cohen, author of Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence, the level of development of society's productive forces (i.e., society's technological powers, including tools, machinery, raw materials, and labor power) determines society's economic structure, in the sense that it selects a structure of economic relations that tends best to facilitate further technological growth. In historical explanation, the overall primacy of the productive forces can be understood in terms of two key theses:

(a) The productive forces tend to develop throughout history (the Development Thesis).

(b) The nature of the production relations of a society is explained by the level of development of its productive forces (the Primacy Thesis proper).

In saying that productive forces have a universal tendency to develop, Cohen's reading of Marx is not claiming that productive forces always develop or that they never decline. Their development may be temporarily blocked, but because human beings have a rational interest in developing their capacities to control their interactions with external nature in order to satisfy their wants, the historical tendency is strongly toward further development of these capacities.

Broadly, the importance of the study of history lies in the ability of history to explain the present. John Bellamy Foster asserts that historical materialism is important in explaining history from a scientific perspective, by following the scientific method, as opposed to belief-system theories like creationism and intelligent design, which do not base their beliefs on verifiable facts and hypotheses.

Modes of production

The main modes of production that Marx identified include primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, capitalism and communism. Mercantilism, mixed economy (state-capitalism) and socialism are sometimes included in the modes of production by later authors. In each of these stages of production, people interact with nature and production in different ways. Any surplus from that production was distributed differently. Marx propounded that humanity first began living in primitive communist societies, then came the ancient societies such as Rome and Greece which were based on a ruling class of citizens and a class of slaves, then feudalism which was based on nobles and serfs, and then capitalism which is based on the capitalist class (bourgeoisie) and the working class (proletariat). In his idea of a future communist society, Marx explains that classes would no longer exist, and therefore the exploitation of one class by another is abolished..

Primitive communism

To historical materialists, hunter-gatherer societies, also known as primitive communist societies, were structured so that economic forces and political forces were one and the same. Societies generally did not have a state, property, money, nor social classes. Due to their limited means of production (hunting and gathering) each individual was only able to produce enough to sustain themselves, thus without any surplus there is nothing to exploit. A slave at this point would only be an extra mouth to feed. This inherently makes them communist in social relations although primitive in productive forces..

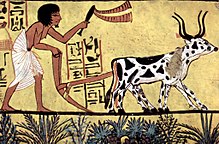

Ancient mode of production

Slave societies, the ancient mode of production, were formed as productive forces advanced, namely due to agriculture and its ensuing abundance which led to the abandonment of nomadic society. Slave societies were marked by their use of slavery and minor private property; production for use was the primary form of production. Slave society is considered by historical materialists to be the first class-stratified society formed of citizens and slaves. Surplus from agriculture was distributed to the citizens, who exploited the slaves that worked the fields.

Feudal mode of production

The feudal mode of production emerged from slave society (e.g. in Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire), coinciding with the further advance of productive forces. Feudal society's class relations were marked by an entrenched nobility and serfdom. Simple commodity production existed in the form of artisans and merchants. This merchant class would grow in size and eventually form the bourgeoisie. However, production was still largely for use.

Capitalist mode of production

The capitalist mode of production materialized when the rising bourgeois class grew large enough to institute a shift in the productive forces. The bourgeoisie's primary form of production was in the form of commodities, i.e. they produced with the purpose of exchanging their products. As this commodity production grew, the old feudal systems came into conflict with the new capitalist ones; feudalism was then eschewed as capitalism emerged. The bourgeoisie's influence expanded until commodity production became fully generalized:

The feudal system of industry, in which industrial production was monopolised by closed guilds, now no longer sufficed for the growing wants of the new markets. The manufacturing system took its place. The guild-masters were pushed on one side by the manufacturing middle class; division of labour between the different corporate guilds vanished in the face of division of labour in each single workshop.

With the rise of the bourgeoisie came the concepts of nation-states and nationalism. Marx argued that capitalism completely separated the economic and political forces. Marx took the state to be a sign of this separation—it existed to manage the massive conflicts of interest which arose between the proletariat and bourgeoisie in capitalist society. Marx observed that nations arose at the time of the appearance of capitalism on the basis of community of economic life, territory, language, certain features of psychology, and traditions of everyday life and culture. In The Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels explained that the coming into existence of nation-states was the result of class struggle, specifically of the capitalist class's attempts to overthrow the institutions of the former ruling class. Prior to capitalism, nations were not the primary political form. Vladimir Lenin shared a similar view on nation-states. There were two opposite tendencies in the development of nations under capitalism. One of them was expressed in the activation of national life and national movements against the oppressors. The other was expressed in the expansion of links among nations, the breaking down of barriers between them, the establishment of a unified economy and of a world market (globalization); the first is a characteristic of lower-stage capitalism and the second a more advanced form, furthering the unity of the international proletariat.[51] Alongside this development was the forced removal of the serfdom from the countryside to the city, forming a new proletarian class. This caused the countryside to become reliant on large cities. Subsequently, the new capitalist mode of production also began expanding into other societies that had not yet developed a capitalist system (e.g. the scramble for Africa). The Communist Manifesto stated:

National differences and antagonism between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.

The supremacy of the proletariat will cause them to vanish still faster. United action, of the leading civilised countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.

Under capitalism, the bourgeoisie and proletariat become the two primary classes. Class struggle between these two classes was now prevalent. With the emergence of capitalism, productive forces were now able to flourish, causing the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Despite this, however, the productive forces eventually reach a point where they can no longer expand, causing the same collapse that occurred at the end of feudalism:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. [...] The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property.

Communist mode of production

Lower-stage of communism

The bourgeoisie, as Marx stated in The Communist Manifesto, has "forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians." Historical materialists henceforth believe that the modern proletariat are the new revolutionary class in relation to the bourgeoisie, in the same way that the bourgeoisie was the revolutionary class in relation to the nobility under feudalism. The proletariat, then, must seize power as the new revolutionary class in a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

Marx also describes a communist society developed alongside the proletarian dictatorship:

Within the co-operative society based on common ownership of the means of production, the producers do not exchange their products; just as little does the labor employed on the products appear here as the value of these products, as a material quality possessed by them, since now, in contrast to capitalist society, individual labor no longer exists in an indirect fashion but directly as a component part of total labor. The phrase "proceeds of labor", objectionable also today on account of its ambiguity, thus loses all meaning. What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society—after the deductions have been made—exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labor. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor cost. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.

This lower-stage of communist society is, according to Marx, analogous to the lower-stage of capitalist society, i.e. the transition from feudalism to capitalism, in that both societies are "stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges." The emphasis on the idea that modes of production do not exist in isolation but rather are materialized from the previous existence is a core idea in historical materialism.

There is considerable debate among communists regarding the nature of this society. Some such as Joseph Stalin, Fidel Castro, and other Marxist-Leninists believe that the lower-stage of communism constitutes its own mode of production, which they call socialist rather than communist. Marxist-Leninists believe that this society may still maintain the concepts of property, money, and commodity production.

Higher-stage of communism

To Marx, the higher-stage of communist society is a free association of producers which has successfully negated all remnants of capitalism, notably the concepts of states, nationality, sexism, families, alienation, social classes, money, property, commodities, the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, division of labor, cities and countryside, class struggle, religion, ideology, and markets. It is the negation of capitalism.

Marx made the following comments on the higher-phase of communist society:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life's prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!

Warnings against misuse

In the 1872 Preface to the French edition of Das Kapital Vol. 1, Marx emphasized that "[t]here is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits." Reaching a scientific understanding required conscientious, painstaking research, instead of philosophical speculation and unwarranted, sweeping generalizations. Having abandoned abstract philosophical speculation in his youth, Marx himself showed great reluctance during the rest of his life about offering any generalities or universal truths about human existence or human history.

The first explicit and systematic summary of the materialist interpretation of history to be published was Engels's book Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science, written with Marx's approval and guidance, and often referred to as the Anti-Dühring. One of the polemics was to ridicule the easy "world schematism" of philosophers, who invented the latest wisdom from behind their writing desks. Towards the end of his life, in 1877, Marx wrote a letter to the editor of the Russian paper Otetchestvennye Zapisky, which significantly contained the following disclaimer:

Russia... will not succeed without having first transformed a good part of her peasants into proletarians; and after that, once taken to the bosom of the capitalist regime, she will experience its pitiless laws like other profane peoples. That is all. But that is not enough for my critic. He feels obliged to metamorphose my historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into an historico-philosophic theory of the marche generale imposed by fate upon every people, whatever the historic circumstances in which it finds itself, in order that it may ultimately arrive at the form of economy which will ensure, together with the greatest expansion of the productive powers of social labour, the most complete development of man. But I beg his pardon. (He is both honouring and shaming me too much.)

Marx goes on to illustrate how the same factors can in different historical contexts produce very different results so that quick and easy generalizations are not really possible. To indicate how seriously Marx took research when he died, his estate contained several cubic metres of Russian statistical publications (it was, as the old Marx observed, in Russia that his ideas gained the most influence)..

Insofar as Marx and Engels regarded historical processes as law-governed processes, the possible future directions of historical development were to a great extent limited and conditioned by what happened before. Retrospectively, historical processes could be understood to have happened by necessity in certain ways and not others, and to some extent at least, the most likely variants of the future could be specified on the basis of careful study of the known facts.

Towards the end of his life, Engels commented several times about the abuse of historical materialism..

In a letter to Conrad Schmidt dated 5 August 1890, he stated:

And if this man [i.e., Paul Barth] has not yet discovered that while the material mode of existence is the primum agens [first agent] this does not preclude the ideological spheres from reacting upon it in their turn, though with a secondary effect, he cannot possibly have understood the subject he is writing about. [...] The materialist conception of history has a lot of [dangerous friends] nowadays, to whom it serves as an excuse for not studying history. Just as Marx used to say, commenting on the French "Marxists" of the late 70s: "All I know is that I am not a Marxist." [...] In general, the word "materialistic" serves many of the younger writers in Germany as a mere phrase with which anything and everything is labelled without further study, that is, they stick to this label and then consider the question disposed of. But our conception of history is above all a guide to study, not a lever for construction after the manner of the Hegelian. All history must be studied afresh, and the conditions of existence of the different formations of society must be examined individually before the attempt is made to deduce them from the political, civil law, aesthetic, philosophic, religious, etc., views corresponding to them. Up to now but little has been done here because only a few people have got down to it seriously. In this field we can utilize heaps of help, it is immensely big, and anyone who will work seriously can achieve much and distinguish himself. But instead of this too many of the younger Germans simply make use of the phrase historical materialism (and everything can be turned into a phrase) only in order to get their own relatively scanty historical knowledge—for economic history is still in its swaddling clothes!—constructed into a neat system as quickly as possible, and they then deem themselves something very tremendous. And after that, a Barth can come along and attack the thing itself, which in his circle has indeed been degraded to a mere phrase.

Finally, in a letter to Franz Mehring dated 14 July 1893, Engels stated:

[T]here is only one other point lacking, which, however, Marx and I always failed to stress enough in our writings and in regard to which we are all equally guilty. That is to say, we all laid, and were bound to lay, the main emphasis, in the first place, on the derivation of political, juridical and other ideological notions, and of actions arising through the medium of these notions, from basic economic facts. But in so doing we neglected the formal side—the ways and means by which these notions, etc., come about—for the sake of the content. This has given our adversaries a welcome opportunity for misunderstandings, of which Paul Barth is a striking example.

Engels warned about conceiving of Marx's ideas as deterministic, saying: "According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. Other than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase." On another occasion, Engels remarked that "younger people sometimes lay more stress on the economic side than is due to it".

Criticism

Philosopher of science Karl Popper, in The Poverty of Historicism and Conjectures and Refutations, critiqued such claims of the explanatory power or valid application of historical materialism by arguing that it could explain or explain away any fact brought before it, making it unfalsifiable and thus pseudoscientific. Similar arguments were brought by Leszek Kołakowski in Main Currents of Marxism.

In his 1940 essay Theses on the Philosophy of History, scholar Walter Benjamin compares historical materialism to the Turk, an 18th-century device which was promoted as a mechanized automaton which could defeat skilled chess players but actually concealed a human who controlled the machine. Benjamin suggested that, despite Marx's claims to scientific objectivity, historical materialism was actually quasi-religious. Like the Turk, wrote Benjamin, "[t]he puppet called 'historical materialism' is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight." Benjamin's friend and colleague Gershom Scholem would argue that Benjamin's critique of historical materialism was so definitive that, as Mark Lilla would write, "nothing remains of historical materialism [...] but the term itself".

Continued development

In a foreword to his essay Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886), three years after Marx's death, Engels claimed confidently that "the Marxist world outlook has found representatives far beyond the boundaries of Germany and Europe and in all the literary languages of the world." Indeed, in the years after Marx and Engels' deaths, "historical materialism" was identified as a distinct philosophical doctrine and was subsequently elaborated upon and systematized by Orthodox Marxist and Marxist–Leninist thinkers such as Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky, Georgi Plekhanov and Nikolai Bukharin. This occurred despite the fact that many of Marx's earlier works on historical materialism, including The German Ideology, remained unpublished until the 1930s.

The substantivist ethnographic approach of economic anthropologist and sociologist Karl Polanyi bears similarities to historical materialism. Polanyi distinguishes between the formal definition of economics as the logic of rational choice between limited resources and a substantive definition of economics as the way humans make their living from their natural and social environment. In The Great Transformation (1944), Polanyi asserts that both the formal and substantive definitions of economics hold true under capitalism, but that the formal definition falls short when analyzing the economic behavior of pre-industrial societies, whose behavior was more often governed by redistribution and reciprocity. While Polanyi was influenced by Marx, he rejected the primacy of economic determinism in shaping the course of history, arguing that rather than being a realm unto itself, an economy is embedded within its contemporary social institutions, such as the state in the case of the market economy.

Perhaps the most notable recent exploration of historical materialism is G. A. Cohen's Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence, which inaugurated the school of Analytical Marxism. Cohen advances a sophisticated technological-determinist interpretation of Marx "in which history is, fundamentally, the growth of human productive power, and forms of society rise and fall according as they enable or impede that growth."

Jürgen Habermas believes historical materialism "needs revision in many respects", especially because it has ignored the significance of communicative action.

Göran Therborn has argued that the method of historical materialism should be applied to historical materialism as an intellectual tradition, and to the history of Marxism itself.

In the early 1980s, Paul Hirst and Barry Hindess elaborated a structural Marxist interpretation of historical materialism.

Regulation theory, especially in the work of Michel Aglietta draws extensively on historical materialism.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, much of Marxist thought was seen as anachronistic. A major effort to "renew" historical materialism comes from historian Ellen Meiksins Wood, who wrote in 1995 that, "There is something off about the assumption that the collapse of Communism represents a terminal crisis for Marxism. One might think, among other things, that in a period of capitalist triumphalism there is more scope than ever for the pursuit of Marxism's principal project, the critique of capitalism."

[T]he kernel of historical materialism was an insistence on the historicity and specificity of capitalism, and denial that its laws were the universal laws of history...this focus on the specificity of capitalism, as a moment with historical origins as well as an end, with a systemic logic specific to it, encourages a truly historical sense lacking in classical political economy and conventional ideas of progress, and this had potentially fruitful implications for the historical study of other modes of production too.

Referencing Marx's Theses on Feuerbach, Wood argued for historical materialism to be understood as "a theoretical foundation for interpreting the world in order to change it."