In cell biology, the spindle apparatus is the cytoskeletal structure of eukaryotic cells that forms during cell division to separate sister chromatids between daughter cells. It is referred to as the mitotic spindle during mitosis, a process that produces genetically identical daughter cells, or the meiotic spindle during meiosis, a process that produces gametes with half the number of chromosomes of the parent cell.

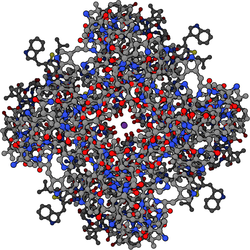

Besides chromosomes, the spindle apparatus is composed of hundreds of proteins. Microtubules comprise the most abundant components of the machinery.

Spindle structure

Attachment of microtubules to chromosomes is mediated by kinetochores, which actively monitor spindle formation and prevent premature anaphase onset. Microtubule polymerization and depolymerization dynamic drive chromosome congression. Depolymerization of microtubules generates tension at kinetochores; bipolar attachment of sister kinetochores to microtubules emanating from opposite cell poles couples opposing tension forces, aligning chromosomes at the cell equator and poising them for segregation to daughter cells. Once every chromosome is bi-oriented, anaphase commences and cohesin, which couples sister chromatids, is severed, permitting the transit of the sister chromatids to opposite poles.

The cellular spindle apparatus includes the spindle microtubules, associated proteins, which include kinesin and dynein molecular motors, condensed chromosomes, and any centrosomes or asters that may be present at the spindle poles depending on the cell type. The spindle apparatus is vaguely ellipsoid in cross section and tapers at the ends. In the wide middle portion, known as the spindle midzone, antiparallel microtubules are bundled by kinesins. At the pointed ends, known as spindle poles, microtubules are nucleated by the centrosomes in most animal cells. Acentrosomal or anastral spindles lack centrosomes or asters at the spindle poles, respectively, and occur for example during female meiosis in most animals. In this instance, a Ran GTP gradient is the main regulator of spindle microtubule organization and assembly. In fungi, spindles form between spindle pole bodies embedded in the nuclear envelope, which does not break down during mitosis.

Microtubule-associated proteins and spindle dynamics

The dynamic lengthening and shortening of spindle microtubules, through a process known as dynamic instability determines to a large extent the shape of the mitotic spindle and promotes the proper alignment of chromosomes at the spindle midzone. Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) associate with microtubules at the midzone and the spindle poles to regulate their dynamics. γ-tubulin is a specialized tubulin variant that assembles into a ring complex called γ-TuRC which nucleates polymerization of α/β tubulin heterodimers into microtubules. Recruitment of γ-TuRC to the pericentrosomal region stabilizes microtubule minus-ends and anchors them near the microtubule-organizing center. The microtubule-associated protein Augmin acts in conjunction with γ-TURC to nucleate new microtubules off of existing microtubules.

The growing ends of microtubules are protected against catastrophe by the action of plus-end microtubule tracking proteins (+TIPs) to promote their association with kinetochores at the midzone. CLIP170 was shown to localize near microtubule plus-ends in HeLa cells and to accumulate in kinetochores during prometaphase. Although how CLIP170 recognizes plus-ends remains unclear, it has been shown that its homologues protect against catastrophe and promote rescue, suggesting a role for CLIP170 in stabilizing plus-ends and possibly mediating their direct attachment to kinetochores. CLIP-associated proteins like CLASP1 in humans have also been shown to localize to plus-ends and the outer kinetochore as well as to modulate the dynamics of kinetochore microtubules (Maiato 2003). CLASP homologues in Drosophila, Xenopus, and yeast are required for proper spindle assembly; in mammals, CLASP1 and CLASP2 both contribute to proper spindle assembly and microtubule dynamics in anaphase. Plus-end polymerization may be further moderated by the EB1 protein, which directly binds the growing ends of microtubules and coordinates the binding of other +TIPs.

Opposing the action of these microtubule-stabilizing proteins are a number of microtubule-depolymerizing factors which permit the dynamic remodeling of the mitotic spindle to promote chromosome congression and attainment of bipolarity. The kinesin-13 superfamily of MAPs contains a class of plus-end-directed motor proteins with associated microtubule depolymerization activity including the well-studied mammalian MCAK and Xenopus XKCM1. MCAK localizes to the growing tips of microtubules at kinetochores where it can trigger catastrophe in direct competition with stabilizing +TIP activity. These proteins harness the energy of ATP hydrolysis to induce destabilizing conformational changes in protofilament structure that cause kinesin release and microtubule depolymerization. Loss of their activity results in numerous mitotic defects. Additional microtubule destabilizing proteins include Op18/stathmin and katanin which have roles in remodeling the mitotic spindle as well as promoting chromosome segregation during anaphase.

The activities of these MAPs are carefully regulated to maintain proper microtubule dynamics during spindle assembly, with many of these proteins serving as Aurora and Polo-like kinase substrates.

Organizing the spindle apparatus

In a properly formed mitotic spindle, bi-oriented chromosomes are aligned along the equator of the cell with spindle microtubules oriented roughly perpendicular to the chromosomes, their plus-ends embedded in kinetochores and their minus-ends anchored at the cell poles. The precise orientation of this complex is required to ensure accurate chromosome segregation and to specify the cell division plane. However, it remains unclear how the spindle becomes organized. Two models predominate the field, which are synergistic and not mutually exclusive. In the search-and-capture model, the spindle is predominantly organized by the poleward separation of centrosomal microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs). Spindle microtubules emanate from centrosomes and 'seek' out kinetochores; when they bind a kinetochore they become stabilized and exert tension on the chromosomes. In an alternative self assembly model, microtubules undergo acentrosomal nucleation among the condensed chromosomes. Constrained by cellular dimensions, lateral associations with antiparallel microtubules via motor proteins, and end-on attachments to kinetochores, microtubules naturally adopt a spindle-like structure with chromosomes aligned along the cell equator.

Centrosome-mediated "search-and-capture" model

In this model, microtubules are nucleated at microtubule organizing centers and undergo rapid growth and catastrophe to 'search' the cytoplasm for kinetochores. Once they bind a kinetochore, they are stabilized and their dynamics are reduced. The newly mono-oriented chromosome oscillates in space near the pole to which it is attached until a microtubule from the opposite pole binds the sister kinetochore. This second attachment further stabilizes kinetochore attachment to the mitotic spindle. Gradually, the bi-oriented chromosome is pulled towards the center of the cell until microtubule tension is balanced on both sides of the centromere; the congressed chromosome then oscillates at the metaphase plate until anaphase onset releases cohesion of the sister chromatids.

In this model, microtubule organizing centers are localized to the cell poles, their separation driven by microtubule polymerization and 'sliding' of antiparallel spindle microtubules with respect to one another at the spindle midzone mediated by bipolar, plus-end-directed kinesins. Such sliding forces may account not only for spindle pole separation early in mitosis, but also spindle elongation during late anaphase.

Chromatin-mediated self-organization of the mitotic spindle

In contrast to the search-and-capture mechanism in which centrosomes largely dictate the organization of the mitotic spindle, this model proposes that microtubules are nucleated acentrosomally near chromosomes and spontaneously assemble into anti-parallel bundles and adopt a spindle-like structure. Classic experiments by Heald and Karsenti show that functional mitotic spindles and nuclei form around DNA-coated beads incubated in Xenopus egg extracts and that bipolar arrays of microtubules are formed in the absence of centrosomes and kinetochores. Indeed, it has also been shown that laser ablation of centrosomes in vertebrate cells inhibits neither spindle assembly nor chromosome segregation. Under this scheme, the shape and size of the mitotic spindle are a function of the biophysical properties of the cross-linking motor proteins.

Chromatin-mediated microtubule nucleation by the Ran GTP gradient

The guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the small GTPase Ran (Regulator of chromosome condensation 1 or RCC1) is attached to nucleosomes via core histones H2A and H2B. Thus, a gradient of GTP-bound Ran is generated around the vicinity of mitotic chromatin. Glass beads coated with RCC1 induce microtubule nucleation and bipolar spindle formation in Xenopus egg extracts, revealing that the Ran GTP gradient alone is sufficient for spindle assembly. The gradient triggers release of spindle assembly factors (SAFs) from inhibitory interactions via the transport proteins importin β/α. The unbound SAFs then promote microtubule nucleation and stabilization around mitotic chromatin, and spindle bipolarity is organized by microtubule motor proteins.

Regulation of spindle assembly

Spindle assembly is largely regulated by phosphorylation events catalyzed by mitotic kinases. Cyclin dependent kinase complexes (CDKs) are activated by mitotic cyclins, whose translation increases during mitosis. CDK1 (also called CDC2) is considered the main mitotic kinase in mammalian cells and is activated by Cyclin B1. Aurora kinases are required for proper spindle assembly and separation. Aurora A associates with centrosomes and is believed to regulate mitotic entry. Aurora B is a member of the chromosomal passenger complex and mediates chromosome-microtubule attachment and sister chromatid cohesion. Polo-like kinase, also known as PLK, especially PLK1 has important roles in the spindle maintenance by regulating microtubule dynamics.

Mitotic chromosome structure

By the end of DNA replication, sister chromatids are bound together in an amorphous mass of tangled DNA and protein. Mitotic entry triggers a dramatic reorganization of the duplicated genome, resulting in sister chromatids that are disentangled and separated from one another. Chromosomes also shorten in length, up to 10,000-fold in animal cells, in a process called condensation. Condensation begins in prophase and chromosomes are maximally compacted into rod-shaped structures by the time they are aligned in the middle of the spindle at metaphase. This gives mitotic chromosomes the classic "X" shape seen in karyotypes, with each condensed sister chromatid linked along their lengths by cohesin proteins and joined, often near the center, at the centromere.

While these dynamic rearrangements are vitally important to ensure accurate and high-fidelity segregation of the genome, our understanding of mitotic chromosome structure remains largely incomplete. A few specific molecular players have been identified, however: Topoisomerase II uses ATP hydrolysis to catalyze decatenation of DNA entanglements, promoting sister chromatid resolution. Condensins are 5-subunit complexes that also use ATP-hydrolysis to promote chromosome condensation. Experiments in Xenopus egg extracts have also implicated linker Histone H1 as an important regulator of mitotic chromosome compaction.

Mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint

The completion of spindle formation is a crucial transition point in the cell cycle called the spindle assembly checkpoint. If chromosomes are not properly attached to the mitotic spindle by the time of this checkpoint, the onset of anaphase will be delayed. Failure of this spindle assembly checkpoint can result in aneuploidy and may be involved in aging and the formation of cancer.

Spindle apparatus orientation

Cell division orientation is of major importance for tissue architecture, cell fates and morphogenesis. Cells tend to divide along their long axis according to the so-called Hertwig rule. The axis of cell division is determined by the orientation of the spindle apparatus. Cells divide along the line connecting two centrosomes of the spindle apparatus. After formation, the spindle apparatus undergoes rotation inside the cell. The astral microtubules originating from centrosomes reach the cell membrane where they are pulled towards specific cortical clues. In vitro, the distribution of cortical clues is set up by the adhesive pattern. In vivo polarity cues are determined by localization of Tricellular junctions localized at cell vertices. The spatial distribution of cortical clues leads to the force field that determine final spindle apparatus orientation and the subsequent orientation of cell division.