The local government of Arlington County, Virginia encourages transit-oriented development within 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 mile (400 to 800 m) from the County's Washington Metro rapid transit stations, with mixed-use development, bikesharing and walkability.

Union Square, a transit-oriented development centred on Kowloon Station, Hong Kong

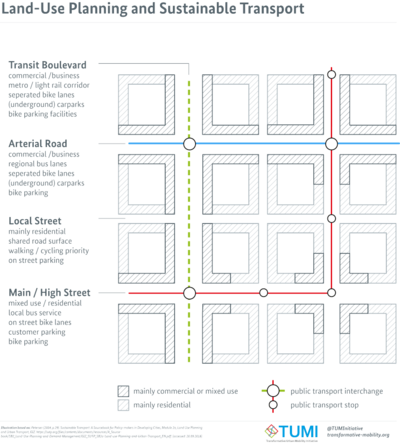

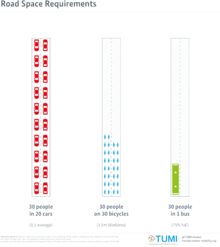

In urban planning, a transit-oriented development (TOD) is a type of urban development that maximizes the amount of residential, business and leisure space within walking distance of public transport. It promotes a symbiotic relationship between dense, compact urban form and public transport use. In doing so, TOD aims to increase public transport ridership by reducing the use of private cars and by promoting sustainable urban growth.

A TOD typically includes a central transit stop (such as a train station, or light rail or bus stop) surrounded by a high-density mixed-use area, with lower-density areas spreading out from this center. A TOD is also typically designed to be more walkable than other built-up areas, through using smaller block sizes and reducing the land area dedicated to automobiles.

The densest areas of a TOD are normally located within a radius

of ¼ to ½ mile (400 to 800 m) around the central transit stop, as this

is considered to be an appropriate scale for pedestrians, thus solving the last mile problem.

Description

A Short History of Traffic Engineering

Many of the new towns created after World War II in Japan, Sweden, and France have many of the characteristics of TOD communities. In a sense, nearly all communities built on reclaimed land in the Netherlands or as exurban developments in Denmark have had the local equivalent of TOD principles integrated in their planning, including the promotion of bicycles for local use.

In the United States, a half-mile-radius circle has become the de

facto standard for rail-transit catchment areas for TODs. A half mile

(800 m) corresponds to the distance someone can walk in 10 minutes at

3 mph (4.8 km/h) and is a common estimate for the distance people will

walk to get to a rail station. The half-mile ring is a little more than

500 acres (2.0 km2) in size.

Transit-oriented development is sometimes distinguished by some planning officials from "transit-proximate development" (see, e.g., comments made during a Congressional hearing)

because it contains specific features that are designed to encourage

public transport use and differentiate the development from urban sprawl. A few examples of these features include mixed-use development that will use transit at all times of day, excellent pedestrian facilities such as high quality pedestrian crossings,

narrow streets, and tapering of buildings as they become more distant

from the public transport node. Another key feature of transit-oriented

development that differentiates it from "transit-proximate development"

is reduced amounts of parking for personal vehicles.

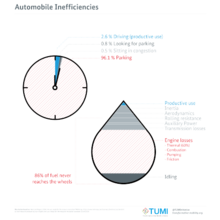

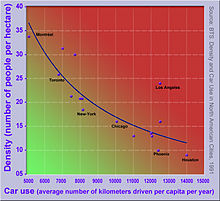

Opponents of compact, or transit oriented development typically

argue that Americans, and persons throughout the world, prefer

low-density living, and that any policies that encourage compact

development will result in substantial utility decreases and hence large social welfare costs. Proponents of compact development argue that there are large, often unmeasured benefits of compact development

or that the American preference for low-density living is a

misinterpretation made possible in part by substantial local government

interference in the land market.

TOD in cities

Many cities throughout the world are developing TOD policy. Toronto, Portland, Montreal, San Francisco, and Vancouver among many other cities have developed, and continue to write policies and strategic plans, which aim to reduce automobile dependency and increase the use of public transit.

Latin America

Curitiba, Brazil

One of the earliest and most successful examples of TOD is Curitiba, Brazil.

Curitiba was organized into transport corridors very early on in its

history. Over the years, it has integrated its zoning laws and

transportation planning to place high-density development adjacent to

high-capacity transportation systems, particularly its BRT corridors.

Since the failure of its first rather grandiose city plan due to lack

of funding, Curitiba has focused on working with economical forms of

infrastructure, so it has arranged unique adaptations, such as bus

routes (inexpensive infrastructure) with routing systems, limited access

and speeds similar to subway systems. The source of innovation in

Curitiba has been a unique form of participatory city planning that

emphasizes public education, discussion and agreement.

Guatemala City, Guatemala

In an attempt to control rapid growth of Guatemala City, the long-time Mayor of Guatemala City Álvaro Arzú

implemented a plan to control growth based on transects along important

arterial roads and exhibiting transit-oriented development (TOD)

characteristics. This plan adopted POT (Plan de Ordenamiento

Territorial) aims to allow the construction of taller, mixed-use

building structures right by large arterial roads; the buildings would

gradually decrease in height and density the farther they are from

arterial roads. This is simultaneously being implemented along with a bus rapid transit (BRT) system called Transmetro.

Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico

City has battled pollution for years. Many attempts have been made to

orient citizens towards public transportation. Expansion of metro line,

both subway and bus, have been instrumental. Following the example of

Curtiba, many bus-lines were created on many of Mexico City's most

important streets. The bus-line has taken two lanes from cars to be used

only by the bus-line, increasing the flow for bus transit.

The city has also made great attempts at increasing the number of

bike lanes, including shutting down entire roads on certain days to be

used only by bikers.

Car regulations have also increased in the city. New regulations

prevent old cars from driving in the city, other cars from driving on

certain days. Electric cars are allowed to be driven everyday and have

free parking. Decreasing the public space allocated to cars and

increasing regulations have become a great annoyance among daily car

users. The city hopes to push people to use more public transport.

North America

Canada

Edmonton, Alberta

Most

of the suburban high rises were not along major rail lines like other

cities until recently, when there has been incentive to do so. Century Park is a growing condo community in southern Edmonton at the south end of Edmonton's LRT.

It will include low to high rise condos, recreational services, shops,

restaurants, and a fitness centre. Edmonton has also had a

transit-proximate development for some time in the northeastern suburbs

at Clareview

which includes a large park and ride, and low rise apartments among big

box stores and associated power center parking. Edmonton is also

looking into some new TODs in various parts of the city. In the

northeast, there are plans to redevelop underutilized land at two sites

around existing LRT, Fort Road and Stadium station. In the west, there is plans to have some medium density condos in the Glenora neighbourhood along a future LRT route as well as a TOD in the southeast in the Strathearn neighbourhood along the same future LRT on existing low rise apartments.

Montreal, Quebec

According to the Metropolitan Development and Planning Regulation of late 2011, 40% of new households will be built as TOD neighbourhoods.

Ottawa, Ontario

Ottawa's City Council has established transit-oriented development (TOD) priority areas in proximity to Ottawa's Light Rail Transit.

These priority areas are a mix of moderate to high-density

transit-supportive developments within a 600-metre walking distance of

rapid transit stations.

Toronto, Ontario

Toronto has a longstanding policy of encouraging new construction along the route of its primary Yonge Street subway line. Most notable are the development of the Yonge and Eglinton area in the 1960s and 1970s; and the present development

of the 2 km of the Yonge Street corridor north of Sheppard Avenue,

which began in the late 1980s. In the period since 1997 alone the

latter stretch has seen the appearance of a major new shopping centre and the building and occupation of over twenty thousand new units of condominium housing. Since the opening of the Sheppard subway line in 2002, there is a condominium construction boom along the route on Sheppard Avenue East between Yonge Street and Don Mills Road.

Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver has a strong history of creating new development around its SkyTrain lines and building regional town centres at major stations and transit corridors. Of note is the Metrotown area of the suburb of Burnaby, British Columbia near the Metrotown SkyTrain Station.

The areas around stations have spurred the development of billions of

dollars of high-density real estate, with multiple highrises near the

many stations, prompting concerns about rapid gentrification.

Winnipeg, Manitoba

There is currently one TOD being built in Winnipeg beside the rapid transit corridor. It is known as The Yards at Fort Rouge,

and was spearheaded by the developer Gem Equities. In phase two of the

southwest rapid transit corridor, there will be four more TODs.

This phase is an interesting example of the use of fine arts in

parallel with transit planning, making several of the stations sites for

public art related to the social history of the area.

United States

Arlington County, Virginia

Aerial view of Rosslyn-Ballston corridor in Arlington, Virginia. High density, mixed use development is concentrated within ¼–½ mile from the Rosslyn, Court House and Clarendon Washington Metro stations (shown in red), with limited density outside that area.

Street-level view of the area around the Ballston Metro Station — also in Arlington, Virginia. Note the mixed-use development (from left to right: ground floor retail

under apartment building, office buildings, shopping mall (at the end

of the street), apartment building, office building with ground floor

retail), pedestrian oriented facilities including wide sidewalk, and bus stop facility in the center distance. Parking in this location is limited, relatively expensive, and located underground.

For over 30 years, the government has pursued a development strategy of concentrating much of its new development within 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 mile (400 to 800 m) from the County's Washington Metro rapid transit stations and the high-volume bus lines of Columbia Pike. Within the transit areas, the government has a policy of encouraging mixed-use and pedestrian- and transit-oriented development. Some of these "urban village" communities include: Rosslyn, Ballston, Clarendon, Courthouse, Pentagon City, Crystal City, Lyon Village, Shirlington, Virginia Square, and Westover

In 2002, Arlington received the EPA's National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for "Overall Excellence in Smart Growth" — the first ever granted by the agency.

In September 2010, Arlington County, Virginia, in partnership with Washington, D.C., opened Capital Bikeshare, a bicycle sharing system. By February 2011, Capital Bikeshare had 14 stations in the Pentagon City, Potomac Yard, and Crystal City neighborhoods in Arlington.

Arlington County also announced plans to add 30 stations in fall 2011,

primarily along the densely populated corridor between the Rosslyn and Ballston neighborhoods, and 30 more in 2012.

Aurora, Colorado

The

city has developed within its plan as of 2007 standardization measures.

For instance, streets' width has been set according to the position of

the site.

New Jersey

New Jersey has become a national leader in promoting transit oriented development. The New Jersey Department of Transportation

established the Transit Village Initiative in 1999, offering

multi-agency assistance and grants from the annual $1 million fund to

any municipality with a ready-to-go project specifying appropriate mixed

land-use strategy, available property, station-area management, and

commitment to affordable housing, job growth, and culture. Transit

village development must also preserve the architectural integrity of

historically significant buildings. Since 1999 the state has numerous

Transit Village designations, which are in different stages of

development:

Pleasantville (1999), Morristown (1999), Rutherford (1999), South Amboy (1999), South Orange (1999), Riverside (2001), Rahway (2002), Metuchen (2003), Belmar (2003), Bloomfield (2003), Bound Brook (2003), Collingswood (2003), Cranford (2003) Matawan (2003), New Brunswick (2005), Journal Square/Jersey City (2005), Netcong (2005), Midtown Elizabeth (2007), Burlington City (2007), Orange (2009), Montclair (2010), Somerville (2010), Linden (2010), West Windsor (2012), Dunellen (2012), Plainfield (2014), Park Ridge (2015), and Irvington (2015).

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The East Liberty

neighborhood is nearing completion of a $150 million Transit Oriented

Development centered around the reconfigured East Liberty Station on the

city's Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway.

The development included improved access to the station with a new

pedestrian bridge and pedestrian walkways that increase the effective

walkshed of the station. The East Busway is a fixed guideway route that

offers riders an 8-minute ride from East Liberty to Pittsburgh's

Downtown.

Salt Lake City Metro Area, Utah

The Salt Lake City Metro Area has seen a strong proliferation of transit-oriented developments due to the construction of new transit lines within the Utah Transit Authority's TRAX, FrontRunner and streetcar lines. New developments in West Valley, Farmington, Murray, Provo, Kaysville, Sugarhouse and downtown Salt Lake City have seen rapid growth and construction despite the economic downturn. The population along the Wasatch Front

has reached 2.5 million and is expected to grow 50% over the next two

decades. At 29.8%, Utah's population growth more than doubled the

population growth of the nation (13.2%), with a vast majority of this

growth occurring along the Wasatch Front.

Transportation infrastructure has been vastly upgraded in the past decade as a result of the 2002 Olympic Winter Games

and the need to support the growth in population. This has created a

number of transit-oriented commercial and residential projects to be

proposed and completed.

San Francisco Bay Area, California

The San Francisco Bay Area includes nine counties and 101 cities, including San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland and Fremont. Local and regional governments

encourage transit-oriented development to decrease traffic congestion,

protect natural areas, promote public health and increase housing

options. The region has designated Priority Development Areas and Priority Conservation Areas. Current population forecasts for the region predict that it will grow by 2 million people by 2035

due to both the natural birth rate and job creation, and estimate that

50% of this growth can be accommodated in Priority Development Areas

through transit-oriented development.

Major transit village projects have been developed over the past 20 years at several stations linked to the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. In their 1996 book, Transit Villages in the 21st Century, Michael Bernick and Robert Cervero identified emerging transit villages at several BART stations, including Pleasant Hill / Contra Costa Centre, Fruitvale, Hayward and Richmond.[43] MacArthur Station is a relatively new development, with construction beginning in 2011 and scheduled for completion after 2019.

Asia and Oceania

Hong Kong

Sha Tin town centre, built around the Sha Tin railway station

Compared to other developed economies, the car ownership rate in Hong

Kong is very low, and approximately 90% of all trips are made by public

transport.

In the mid-20th century, no railway was built until an area was well developed. However, in recent decades, Hong Kong

has started to have some TODs, where a railway is built simultaneously

with residential development above or nearby, dubbed the "Rail plus

Property" (R+P) Model. Examples include:

Malaysia

Bandar Malaysia is an upcoming development by 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB).

Indonesia

Many TOD are now being constructed in Greater Jakarta metro area such as Citra Sentul Raya and Dukuh Atas TOD. TOD are also being constructed in cities like Surabaya, Medan, and Palembang.

Melbourne, Victoria

Chatswood Station in Sydney. Trains run through the integrated station, shopping and apartment complex

Melbourne, Victoria

is expected to reach a population of 5 million by 2030 with the

overwhelming majority of its residents relying on private automobiles.

Since the turn of the century, sporadic efforts have been made by

various levels of government to implement transit-oriented development

principles. However, a lack of commitment to funding public transport

infrastructure, resulting to overcrowding and amending zoning laws has

dramatically slowed progress toward sustainable development for the city.

Milton, Queensland

Milton, an inner suburb of Brisbane, has been identified as Queensland's first transit-oriented development under the Queensland Government's South East Queensland Regional Plan. Milton railway station will undergo a multimillion-dollar revamp as part of the development of The Milton Residences

to promote and encourage residents to embrace rail travel. This will

include a new ticketing office, new public amenities, increased

visibility across platforms and new and improved access points off

Milton Road and Railway Terrace.

Sydney, New South Wales

The New South Wales state government has actively encouraged developments around stations on the Sydney Trains and Sydney Metro networks through its Priority Precincts plan. Several stations such as Chatswood, Burwood, Parramatta and Rhodes

have large scale apartment developments built within close proximity

within the past decade. New apartment and office tower developments

along the future Sydney Metro stations are being planned as integrated

developments with the stations themselves. Examples of this include Victoria Cross Station and Crows Nest Station whilst existing stations such as Castle Hill and Epping have also had intensified development.

Europe

Karen Blixen Park, Ørestad (Copenhagen), Denmark

The term transit-oriented development, as a US-born concept, is

rarely used in Europe, although many of the measures advocated in US

transit-oriented development are also stressed in Europe. Many European

cities have long been built around transit systems and there has thus

often been little or no need to differentiate this type of development

with a special term as has been the case in the US. An example of this

is Copenhagen's Finger Plan

from 1947, which embodied many transit-oriented development aspects and

is still used as an overall planning framework today. Recently,

scholars and technicians have taken interest in the concept, however.

Paris, France

Whereas the city of Paris has a centuries-long history, its main frame dates to the 19th century. The subway network

was made to solve both linkage between the five main train stations and

local transportation assets for citizens. The whole area of Paris City

has metro stations no more than 500 metres apart. Recent bicycle and car

rental systems (Velib and Autolib)

also ease travel, in the very same way that TOD emphasizes. So do the

new trams linking suburbs close to Paris proper, and tramline 3 around

the edge of the city of Paris.

Stedenbaan, The Netherlands

In the Southern part of the Randstad a neighbourhood according to the principles of TOD will be built.

Equity and housing cost concerns

One criticism of transit-oriented development is that it has the potential to spur gentrification

in low-income areas. In some cases, TOD can raise the housing costs of

formerly affordable neighborhoods, pushing low- and moderate-income

residents farther away from jobs and transit. When this happens, TOD

projects can disrupt low-income neighborhoods.

When executed with equity in mind, however, TOD has the potential

to benefit low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities: it can link

workers to employment centers, create construction and maintenance jobs,

and has the potential to encourage investment in areas that have

suffered neglect and economic depression.

Moreover, it is well recognized that neighborhood development

restrictions, while potentially in the immediate neighborhood's best

interest, contribute to regional undersupply of housing and drive up the

cost of housing in general across a region. TOD reduces the overall

cost of housing in a region by contributing to the housing supply, and

therefore generally improves equity in the housing market. TOD also

reduces transportation costs, which can have a greater impact on LMI

households since they spend a larger share of their income on

transportation relative to higher-income households. This frees up

household income that can be used on food, education, or other necessary

expenses. Low-income people are also less likely to own personal

vehicles and therefore more likely to depend exclusively on public

transportation to get to and from work, making reliable access to

transit a necessity for their economic success.