Traffic in Los Angeles

Automobile dependency or car dependency is the concept that some city layouts cause automobiles to be favoured over alternate forms of transportation, such as bicycles, public transit, and walking.

Overview

In many modern cities automobiles are convenient and sometimes necessary to move easily.

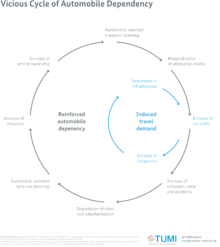

When it comes to automobile use, there is a spiralling effect where traffic congestion produces the 'demand' for more and bigger roads and removal of 'impediments' to traffic flow, such as pedestrians, signalised crossings, traffic lights, cyclists, and various forms of street-based public transit, such as streetcars (trams).

These measures make automobile use more pleasurable and

advantageous at the expense of other modes of transport, so greater

traffic volumes are induced. Additionally, the urban design

of cities adjusts to the needs of automobiles in terms of movement and

space. Buildings are replaced by parking lots. Open air shopping streets

are replaced by enclosed shopping malls.

Walk-in banks and fast-food stores are replaced by drive-in versions of

themselves that are inconveniently located for pedestrians. Town

centres with a mixture of commercial, retail and entertainment functions are replaced by single-function business parks, 'category-killer' retail boxes and 'multiplex' entertainment complexes, each surrounded by large tracts of parking.

These kinds of environments require automobiles to access them,

thus inducing even more traffic onto the increased roadspace. This

results in congestion, and the cycle above continues. Roads get ever

bigger, consuming ever greater tracts of land previously used for

housing, manufacturing and other socially and economically useful

purposes. Public transit becomes less and less viable and socially

stigmatised, eventually becoming a minority form of transportation.

People's choices and freedoms to live functional lives without the use

of the car are greatly reduced. Such cities are automobile dependent.

Automobile dependency is seen primarily as an issue of environmental sustainability due to the consumption of non-renewable resources and production of greenhouse gases responsible for global warming. It is also an issue of social and cultural sustainability. Like gated communities,

the private automobile produces physical separation between people and

reduces the opportunities for unstructured social encounter that is a

significant aspect of social capital formation and maintenance in urban environments.

Negative externalities of automobile

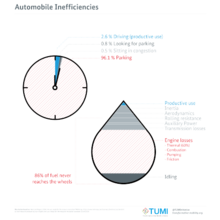

Automobile Inefficiencies

According to the Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector made by the Delft University

and which is the main reference in European Union for assessing the

externalities of cars, the main external costs of driving a car are:

- congestion and scarcity costs,

- collision costs,

- air pollution costs,

- noise pollution costs,

- climate change costs,

- costs for nature and landscape,

- costs for water pollution,

- costs for soil pollution and

- costs of energy dependency.

Addressing the issue

There are a number of planning and design approaches to redressing automobile dependency, known variously as New Urbanism, transit-oriented development, and smart growth. Most of these approaches focus on the physical urban design, urban density and landuse zoning of cities. Dr. Paul Mees, a transport planning academic formerly at the University of Melbourne,

argues that investment in good public transit, centralised management

by the public sector and appropriate policy priorities are more

significant than issues of urban form and density.

There are, of course, many who argue against a number of the

details within any of the complex arguments related to this topic,

particularly relationships between urban density

and transit viability, or the nature of viable alternatives to

automobiles that provide the same degree of flexibility and speed. There

is also research into the future of automobility itself in terms of shared usage, size reduction, roadspace management and more sustainable fuel sources.

Car-sharing is one example of a solution to automobile dependency. Research has shown that in the United States, services like Zipcar, have reduced demand by about 500,000 cars. In the developing world, companies like eHi, Carrot, Zazcar and Zoom

have replicated or modified Zipcar's business model to improve urban

transportation to provide a broader audience with greater access to the

benefits of a car and provide"last-mile" connectivity between public

transportation and an individual's destination. Car sharing also reduces

private vehicle ownership.

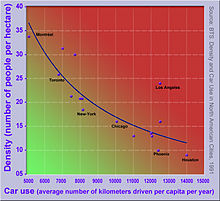

A diagram showing an inverse correlation between urban density and car use for selected North American cities

Urban sprawl and smart growth

Whether smart growth does or can reduce problems of automobile dependency associated with urban sprawl has been fiercely contested for several decades. The influential study in 1989 by Peter Newman and Jeff Kenworthy compared 32 cities across North America, Australia, Europe and Asia. The study has been criticised for its methodology, but the main finding, that denser cities, particularly in Asia, have lower car use than sprawling cities, particularly in North America,

has been largely accepted, but the relationship is clearer at the

extremes across continents than it is within countries where conditions

are more similar.

Within cities, studies from across many countries (mainly in the

developed world) have shown that denser urban areas with greater mixture

of land use and better public transport tend to have lower car use than

less dense suburban and exurban

residential areas. This usually holds true even after controlling for

socio-economic factors such as differences in household composition and

income.

This does not necessarily imply that suburban sprawl

causes high car use, however. One confounding factor, which has been

the subject of many studies, is residential self-selection:

people who prefer to drive tend to move towards low-density suburbs,

whereas people who prefer to walk, cycle or use transit tend to move

towards higher density urban areas, better served by public transport.

Some studies have found that, when self-selection is controlled for, the

built environment has no significant effect on travel behaviour.

More recent studies using more sophisticated methodologies have

generally rejected these findings: density, land use and public

transport accessibility can influence travel behaviour, although social

and economic factors, particularly household income, usually exert a

stronger influence.

The paradox of intensification

Reviewing the evidence on urban intensification, smart growth and their effects on automobile use, Melia et al. (2011) found support for the arguments of both supporters and opponents of smart growth. Planning policies that increase population densities

in urban areas do tend to reduce car use, but the effect is a weak one,

so doubling the population density of a particular area will not halve

the frequency or distance of car use.

These findings led them to propose the paradox of intensification:

- All other things being equal, urban intensification which increases population density will reduce per capita car use, with benefits to the global environment, but will also increase concentrations of motor traffic, worsening the local environment in those locations where it occurs.

At the citywide level, it may be possible, through a range of

positive measures to counteract the increases in traffic and congestion

that would otherwise result from increasing population densities: Freiburg im Breisgau

in Germany is one example of a city which has been more successful in

reducing automobile dependency and constraining increases in traffic

despite substantial increases in population density.

This study also reviewed evidence on the local effects of

building at higher densities. At the level of the neighbourhood or

individual development, positive measures (like improvements to public

transport) will usually be insufficient to counteract the traffic effect

of increasing population density.

This leaves policy-makers with four choices:

- intensify and accept the local consequences

- sprawl and accept the wider consequences

- a compromise with some element of both

- or intensify accompanied by more direct measures such as parking restrictions, closing roads to traffic and carfree zones.