The Fountain of Eternal Life in Cleveland, Ohio is described as symbolizing "Man rising above death, reaching upward to God and toward Peace."[1]

Immortality is eternal life, being exempt from death, unending existence. Some modern species may possess biological immortality.

Certain scientists, futurists, and philosophers have theorized about the immortality of the human body, with some suggesting that human immortality may be achievable in the first few decades of the 21st century. Other advocates believe that life extension is a more achievable goal in the short term, with immortality awaiting further research breakthroughs. The absence of aging would provide humans with biological immortality, but not invulnerability to death by disease or physical trauma; although mind uploading could solve that if it proved possible. Whether the process of internal endoimmortality is delivered within the upcoming years depends chiefly on research (and in neuron research in the case of endoimmortality through an immortalized cell line) in the former view and perhaps is an awaited goal in the latter case.

In religious contexts, immortality is often stated to be one of the promises of God (or other deities) to human beings who show goodness or else follow divine law. What form an unending human life would take, or whether an immaterial soul exists and possesses immortality, has been a major point of focus of religion, as well as the subject of speculation, fantasy, and debate.

Definitions

Scientific

Life extension technologies promise a path to complete rejuvenation. Cryonics holds out the hope that the dead can be revived in the future, following sufficient medical advancements. While, as shown with creatures such as hydra and planarian worms, it is indeed possible for a creature to be biologically immortal, it is not known if it is possible for humans.Mind uploading is the transference of brain states from a human brain to an alternative medium providing similar functionality. Assuming the process to be possible and repeatable, this would provide immortality to the computation of the original brain, as predicted by futurists such as Ray Kurzweil.[4]

Religious

The belief in an afterlife is a fundamental tenet of most religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, and the Bahá'í Faith; however, the concept of an immortal soul is not. The "soul" itself has different meanings and is not used in the same way in different religions and different denominations of a religion. For example, various branches of Christianity have disagreeing views on the soul's immortality and its relation to the body.Physical immortality

Physical immortality is a state of life that allows a person to avoid death and maintain conscious thought. It can mean the unending existence of a person from a physical source other than organic life, such as a computer. Active pursuit of physical immortality can either be based on scientific trends, such as cryonics, digital immortality, breakthroughs in rejuvenation or predictions of an impending technological singularity, or because of a spiritual belief, such as those held by Rastafarians or Rebirthers.Causes of death

There are three main causes of death: aging, disease and physical trauma.[5] Such issues can be resolved with the solutions provided in research to any end providing such alternate theories at present that require unification.Aging

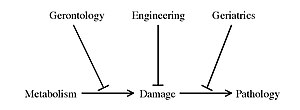

Aubrey de Grey, a leading researcher in the field,[6] defines aging as "a collection of cumulative changes to the molecular and cellular structure of an adult organism, which result in essential metabolic processes, but which also, once they progress far enough, increasingly disrupt metabolism, resulting in pathology and death." The current causes of aging in humans are cell loss (without replacement), DNA damage, oncogenic nuclear mutations and epimutations, cell senescence, mitochondrial mutations, lysosomal aggregates, extracellular aggregates, random extracellular cross-linking, immune system decline, and endocrine changes. Eliminating aging would require finding a solution to each of these causes, a program de Grey calls engineered negligible senescence. There is also a huge body of knowledge indicating that change is characterized by the loss of molecular fidelity.[7]Disease

Disease is theoretically surmountable via technology. In short, it is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism, something the body shouldn't typically have to deal with its natural make up.[8] Human understanding of genetics is leading to cures and treatments for a myriad of previously incurable diseases. The mechanisms by which other diseases do damage are becoming better understood. Sophisticated methods of detecting diseases early are being developed. Preventative medicine is becoming better understood. Neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's may soon be curable with the use of stem cells. Breakthroughs in cell biology and telomere research are leading to treatments for cancer. Vaccines are being researched for AIDS and tuberculosis. Genes associated with type 1 diabetes and certain types of cancer have been discovered, allowing for new therapies to be developed. Artificial devices attached directly to the nervous system may restore sight to the blind. Drugs are being developed to treat a myriad of other diseases and ailments.Trauma

Physical trauma would remain as a threat to perpetual physical life, as an otherwise immortal person would still be subject to unforeseen accidents or catastrophes. The speed and quality of paramedic response remains a determining factor in surviving severe trauma.[9] A body that could automatically repair itself from severe trauma, such as speculated uses for nanotechnology, would mitigate this factor. Being the seat of consciousness, the brain cannot be risked to trauma if a continuous physical life is to be maintained. This aversion to trauma risk to the brain would naturally result in significant behavioral changes that would render physical immortality undesirable for some people.Environmental change

Organisms otherwise unaffected by these causes of death would still face the problem of obtaining sustenance (whether from currently available agricultural processes or from hypothetical future technological processes) in the face of changing availability of suitable resources as environmental conditions change. After avoiding aging, disease, and trauma, you could still starve to death.If there is no limitation on the degree of gradual mitigation of risk then it is possible that the cumulative probability of death over an infinite horizon is less than certainty, even when the risk of fatal trauma in any finite period is greater than zero. Mathematically, this is an aspect of achieving "actuarial escape velocity"

Biological immortality

Human chromosomes (grey) capped by telomeres (white)

Biological immortality is an absence of aging. Specifically it's the absence of a sustained increase in rate of mortality as a function of chronological age. A cell or organism that does not experience aging, or ceases to age at some point, is biologically immortal.

Biologists have chosen the word "immortal" to designate cells that are not limited by the Hayflick limit, where cells no longer divide because of DNA damage or shortened telomeres. The first and still most widely used immortal cell line is HeLa, developed from cells taken from the malignant cervical tumor of Henrietta Lacks without her consent in 1951. Prior to the 1961 work of Leonard Hayflick, there was the erroneous belief fostered by Alexis Carrel that all normal somatic cells are immortal. By preventing cells from reaching senescence one can achieve biological immortality; telomeres, a "cap" at the end of DNA, are thought to be the cause of cell aging. Every time a cell divides the telomere becomes a bit shorter; when it is finally worn down, the cell is unable to split and dies. Telomerase is an enzyme which rebuilds the telomeres in stem cells and cancer cells, allowing them to replicate an infinite number of times.[10] No definitive work has yet demonstrated that telomerase can be used in human somatic cells to prevent healthy tissues from aging. On the other hand, scientists hope to be able to grow organs with the help of stem cells, allowing organ transplants without the risk of rejection, another step in extending human life expectancy. These technologies are the subject of ongoing research, and are not yet realized.[11]

Biologically immortal species

Life defined as biologically immortal is still susceptible to causes of death besides aging, including disease and trauma, as defined above. Notable immortal species include:- Bacteria – Bacteria reproduce through binary fission. A parent bacterium splits itself into two identical daughter cells which eventually then split themselves in half. This process repeats, thus making the bacterium essentially immortal. A 2005 PLoS Biology paper[12] suggests that after each division the daughter cells can be identified as the older and the younger, and the older is slightly smaller, weaker, and more likely to die than the younger.[13]

- Turritopsis dohrnii, a jellyfish (phylum Cnidaria, class Hydrozoa, order Anthoathecata), after becoming a sexually mature adult, can transform itself back into a polyp using the cell conversion process of transdifferentiation.[14] Turritopsis dohrnii repeats this cycle, meaning that it may have an indefinite lifespan.[14] Its immortal adaptation has allowed it to spread from its original habitat in the Caribbean to "all over the world".[15][16]

- Hydra is a genus belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, the class Hydrozoa and the order Anthomedusae. They are simple fresh-water predatory animals possessing radial symmetry.[17][18]

- Bristlecone pines are speculated to be potentially immortal;[citation needed] the oldest known living specimen is over 5,000 years old.

Evolution of aging

As the existence of biologically immortal species demonstrates, there is no thermodynamic necessity for senescence: a defining feature of life is that it takes in free energy from the environment and unloads its entropy as waste. Living systems can even build themselves up from seed, and routinely repair themselves. Aging is therefore presumed to be a byproduct of evolution, but why mortality should be selected for remains a subject of research and debate. Programmed cell death and the telomere "end replication problem" are found even in the earliest and simplest of organisms.[19] This may be a tradeoff between selecting for cancer and selecting for aging.[20]Modern theories on the evolution of aging include the following:

- Mutation accumulation is a theory formulated by Peter Medawar in 1952 to explain how evolution would select for aging. Essentially, aging is never selected against, as organisms have offspring before the mortal mutations surface in an individual.

- Antagonistic pleiotropy is a theory proposed as an alternative by George C. Williams, a critic of Medawar, in 1957. In antagonistic pleiotropy, genes carry effects that are both beneficial and detrimental. In essence this refers to genes that offer benefits early in life, but exact a cost later on, i.e. decline and death.[21]

- The disposable soma theory was proposed in 1977 by Thomas Kirkwood, which states that an individual body must allocate energy for metabolism, reproduction, and maintenance, and must compromise when there is food scarcity. Compromise in allocating energy to the repair function is what causes the body gradually to deteriorate with age, according to Kirkwood.[22]

Prospects for human biological immortality

Life-extending substances

There are some known naturally occurring and artificially produced chemicals that may increase the lifetime or life-expectancy of a person or organism, such as resveratrol.[23][24]Some scientists believe that boosting the amount or proportion of telomerase in the body, a naturally forming enzyme that helps maintain the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, could prevent cells from dying and so may ultimately lead to extended, healthier lifespans. A team of researchers at the Spanish National Cancer Centre (Madrid) tested the hypothesis on mice. It was found that those mice which were genetically engineered to produce 10 times the normal levels of telomerase lived 50% longer than normal mice.[25]

In normal circumstances, without the presence of telomerase, if a cell divides repeatedly, at some point all the progeny will reach their Hayflick limit. With the presence of telomerase, each dividing cell can replace the lost bit of DNA, and any single cell can then divide unbounded. While this unbounded growth property has excited many researchers, caution is warranted in exploiting this property, as exactly this same unbounded growth is a crucial step in enabling cancerous growth. If an organism can replicate its body cells faster, then it would theoretically stop aging.

Embryonic stem cells express telomerase, which allows them to divide repeatedly and form the individual. In adults, telomerase is highly expressed in cells that need to divide regularly (e.g., in the immune system), whereas most somatic cells express it only at very low levels in a cell-cycle dependent manner.

Technological immortality, biological machines, and "swallowing the doctor"

Technological immortality is the prospect for much longer life spans made possible by scientific advances in a variety of fields: nanotechnology, emergency room procedures, genetics, biological engineering, regenerative medicine, microbiology, and others. Contemporary life spans in the advanced industrial societies are already markedly longer than those of the past because of better nutrition, availability of health care, standard of living and bio-medical scientific advances. Technological immortality predicts further progress for the same reasons over the near term. An important aspect of current scientific thinking about immortality is that some combination of human cloning, cryonics or nanotechnology will play an essential role in extreme life extension. Robert Freitas, a nanorobotics theorist, suggests tiny medical nanorobots could be created to go through human bloodstreams, find dangerous things like cancer cells and bacteria, and destroy them.[26] Freitas anticipates that gene-therapies and nanotechnology will eventually make the human body effectively self-sustainable and capable of living indefinitely in empty space, short of severe brain trauma. This supports the theory that we will be able to continually create biological or synthetic replacement parts to replace damaged or dying ones. Future advances in nanomedicine could give rise to life extension through the repair of many processes thought to be responsible for aging. K. Eric Drexler, one of the founders of nanotechnology, postulated cell repair devices, including ones operating within cells and utilizing as yet hypothetical biological machines, in his 1986 book Engines of Creation. Raymond Kurzweil, a futurist and transhumanist, stated in his book The Singularity Is Near that he believes that advanced medical nanorobotics could completely remedy the effects of aging by 2030.[27] According to Richard Feynman, it was his former graduate student and collaborator Albert Hibbs who originally suggested to him (circa 1959) the idea of a medical use for Feynman's theoretical micromachines (see biological machine). Hibbs suggested that certain repair machines might one day be reduced in size to the point that it would, in theory, be possible to (as Feynman put it) "swallow the doctor". The idea was incorporated into Feynman's 1959 essay There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom.[28]Cryonics

Cryonics, the practice of preserving organisms (either intact specimens or only their brains) for possible future revival by storing them at cryogenic temperatures where metabolism and decay are almost completely stopped, can be used to 'pause' for those who believe that life extension technologies will not develop sufficiently within their lifetime. Ideally, cryonics would allow clinically dead people to be brought back in the future after cures to the patients' diseases have been discovered and aging is reversible. Modern cryonics procedures use a process called vitrification which creates a glass-like state rather than freezing as the body is brought to low temperatures. This process reduces the risk of ice crystals damaging the cell-structure, which would be especially detrimental to cell structures in the brain, as their minute adjustment evokes the individual's mind.Mind-to-computer uploading

One idea that has been advanced involves uploading an individual's habits and memories via direct mind-computer interface. The individual's memory may be loaded to a computer or to a new organic body. Extropian futurists like Moravec and Kurzweil have proposed that, thanks to exponentially growing computing power, it will someday be possible to upload human consciousness onto a computer system, and exist indefinitely in a virtual environment. This could be accomplished via advanced cybernetics, where computer hardware would initially be installed in the brain to help sort memory or accelerate thought processes. Components would be added gradually until the person's entire brain functions were handled by artificial devices, avoiding sharp transitions that would lead to issues of identity, thus running the risk of the person to be declared dead and thus not be a legitimate owner of his or her property. After this point, the human body could be treated as an optional accessory and the program implementing the person could be transferred to any sufficiently powerful computer. Another possible mechanism for mind upload is to perform a detailed scan of an individual's original, organic brain and simulate the entire structure in a computer. What level of detail such scans and simulations would need to achieve to emulate awareness, and whether the scanning process would destroy the brain, is still to be determined.[29] Whatever the route to mind upload, persons in this state could then be considered essentially immortal, short of loss or traumatic destruction of the machines that maintained them.[clarification needed]Cybernetics

Transforming a human into a cyborg can include brain implants or extracting a human processing unit and placing it in a robotic life-support system. Even replacing biological organs with robotic ones could increase life span (e.g. pace makers) and depending on the definition, many technological upgrades to the body, like genetic modifications or the addition of nanobots would qualify an individual as a cyborg. Some people believe that such modifications would make one impervious to aging and disease and theoretically immortal unless killed or destroyed.Religious views

As late as 1952, the editorial staff of the Syntopicon found in their compilation of the Great Books of the Western World, that "The philosophical issue concerning immortality cannot be separated from issues concerning the existence and nature of man's soul."[30] Thus, the vast majority of speculation regarding immortality before the 21st century was regarding the nature of the afterlife.Ancient Greek religion

Immortality in ancient Greek religion originally always included an eternal union of body and soul as can be seen in Homer, Hesiod, and various other ancient texts. The soul was considered to have an eternal existence in Hades, but without the body the soul was considered dead. Although almost everybody had nothing to look forward to but an eternal existence as a disembodied dead soul, a number of men and women were considered to have gained physical immortality and been brought to live forever in either Elysium, the Islands of the Blessed, heaven, the ocean or literally right under the ground. Among these were Amphiaraus, Ganymede, Ino, Iphigenia, Menelaus, Peleus, and a great part of those who fought in the Trojan and Theban wars. Some were considered to have died and been resurrected before they achieved physical immortality. Asclepius was killed by Zeus only to be resurrected and transformed into a major deity. In some versions of the Trojan War myth, Achilles, after being killed, was snatched from his funeral pyre by his divine mother Thetis, resurrected, and brought to an immortal existence in either Leuce, the Elysian plains, or the Islands of the Blessed. Memnon, who was killed by Achilles, seems to have received a similar fate. Alcmene, Castor, Heracles, and Melicertes were also among the figures sometimes considered to have been resurrected to physical immortality. According to Herodotus' Histories, the 7th century BC sage Aristeas of Proconnesus was first found dead, after which his body disappeared from a locked room. Later he was found not only to have been resurrected but to have gained immortality.The philosophical idea of an immortal soul was a belief first appearing with either Pherecydes or the Orphics, and most importantly advocated by Plato and his followers. This, however, never became the general norm in Hellenistic thought. As may be witnessed even into the Christian era, not least by the complaints of various philosophers over popular beliefs, many or perhaps most traditional Greeks maintained the conviction that certain individuals were resurrected from the dead and made physically immortal and that others could only look forward to an existence as disembodied and dead, though everlasting, souls. The parallel between these traditional beliefs and the later resurrection of Jesus was not lost on the early Christians, as Justin Martyr argued: "when we say ... Jesus Christ, our teacher, was crucified and died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propose nothing different from what you believe regarding those whom you consider sons of Zeus." (1 Apol. 21).

Buddhism

The goal of Hinayana is Arhatship and Nirvana. By contrast, the goal of Mahayana is Buddhahood.According to one Tibetan Buddhist teaching, Dzogchen, individuals can transform the physical body into an immortal body of light called the rainbow body.

Christianity

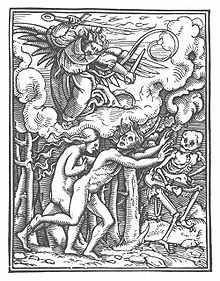

Adam and Eve condemned to mortality. Hans Holbein the Younger, Danse Macabre, 16th century

Christian theology holds that Adam and Eve lost physical immortality for themselves and all their descendants in the Fall of Man, although this initial "imperishability of the bodily frame of man" was "a preternatural condition".[31] Christians who profess the Nicene Creed believe that every dead person (whether they believed in Christ or not) will be resurrected from the dead at the Second Coming, and this belief is known as Universal resurrection.

N.T. Wright, a theologian and former Bishop of Durham, has said many people forget the physical aspect of what Jesus promised. He told Time: "Jesus' resurrection marks the beginning of a restoration that he will complete upon his return. Part of this will be the resurrection of all the dead, who will 'awake', be embodied and participate in the renewal. Wright says John Polkinghorne, a physicist and a priest, has put it this way: 'God will download our software onto his hardware until the time he gives us new hardware to run the software again for ourselves.' That gets to two things nicely: that the period after death (the Intermediate state) is a period when we are in God's presence but not active in our own bodies, and also that the more important transformation will be when we are again embodied and administering Christ's kingdom."[32] This kingdom will consist of Heaven and Earth "joined together in a new creation", he said.

Hinduism

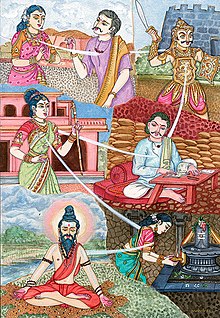

Representation of a soul undergoing punarjanma. Illustration from Hinduism Today, 2004

Hindus believe in an immortal soul which is reincarnated after death. According to Hinduism, people repeat a process of life, death, and rebirth in a cycle called samsara. If they live their life well, their karma improves and their station in the next life will be higher, and conversely lower if they live their life poorly. After many life times of perfecting its karma, the soul is freed from the cycle and lives in perpetual bliss. There is no place of eternal torment in Hinduism, although if a soul consistently lives very evil lives, it could work its way down to the very bottom of the cycle.

There are explicit renderings in the Upanishads alluding to a physically immortal state brought about by purification, and sublimation of the 5 elements that make up the body. For example, in the Shvetashvatara Upanishad (Chapter 2, Verse 12), it is stated "When earth, water fire, air and akasa arise, that is to say, when the five attributes of the elements, mentioned in the books on yoga, become manifest then the yogi's body becomes purified by the fire of yoga and he is free from illness, old age and death."

Another view of immortality is traced to the Vedic tradition by the interpretation of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi:

That man indeed whom these (contacts)To Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the verse means, "Once a man has become established in the understanding of the permanent reality of life, his mind rises above the influence of pleasure and pain. Such an unshakable man passes beyond the influence of death and in the permanent phase of life: he attains eternal life ... A man established in the understanding of the unlimited abundance of absolute existence is naturally free from existence of the relative order. This is what gives him the status of immortal life."[33]

do not disturb, who is even-minded in

pleasure and pain, steadfast, he is fit

for immortality, O best of men.[33]

An Indian Tamil saint known as Vallalar claimed to have achieved immortality before disappearing forever from a locked room in 1874.[34][35]

Judaism

The traditional concept of an immaterial and immortal soul distinct from the body was not found in Judaism before the Babylonian Exile, but developed as a result of interaction with Persian and Hellenistic philosophies. Accordingly, the Hebrew word nephesh, although translated as "soul" in some older English Bibles, actually has a meaning closer to "living being". Nephesh was rendered in the Septuagint as ψυχή (psūchê), the Greek word for soul.The only Hebrew word traditionally translated "soul" (nephesh) in English language Bibles refers to a living, breathing conscious body, rather than to an immortal soul.[36] In the New Testament, the Greek word traditionally translated "soul" (ψυχή) has substantially the same meaning as the Hebrew, without reference to an immortal soul.[37] ‘Soul’ may refer to the whole person, the self: ‘three thousand souls’ were converted in Acts 2:41 (see Acts 3:23).

The Hebrew Bible speaks about Sheol (שאול), originally a synonym of the grave-the repository of the dead or the cessation of existence until the resurrection of the dead. This doctrine of resurrection is mentioned explicitly only in Daniel 12:1–4 although it may be implied in several other texts. New theories arose concerning Sheol during the intertestamental period.

The views about immortality in Judaism is perhaps best exemplified by the various references to this in Second Temple Period. The concept of resurrection of the physical body is found in 2 Maccabees, according to which it will happen through recreation of the flesh.[38] Resurrection of the dead also appears in detail in the extra-canonical books of Enoch,[39] and in Apocalypse of Baruch.[40] According to the British scholar in ancient Judaism Philip R. Davies, there is “little or no clear reference … either to immortality or to resurrection from the dead” in the Dead Sea scrolls texts.[41] Both Josephus and the New Testament record that the Sadducees did not believe in an afterlife,[42] but the sources vary on the beliefs of the Pharisees. The New Testament claims that the Pharisees believed in the resurrection, but does not specify whether this included the flesh or not.[43] According to Josephus, who himself was a Pharisee, the Pharisees held that only the soul was immortal and the souls of good people will be reincarnated and “pass into other bodies,” while “the souls of the wicked will suffer eternal punishment.” [44] Jubilees seems to refer to the resurrection of the soul only, or to a more general idea of an immortal soul.[45]

Rabbinic Judaism claims that the righteous dead will be resurrected in the Messianic Age with the coming of the messiah. They will then be granted immortality in a perfect world. The wicked dead, on the other hand, will not be resurrected at all. This is not the only Jewish belief about the afterlife. The Tanakh is not specific about the afterlife, so there are wide differences in views and explanations among believers.

Taoism

It is repeatedly stated in Lüshi Chunqiu that death is unavoidable.[46] Henri Maspero noted that many scholarly works frame Taoism as a school of thought focused on the quest for immortality.[47] Isabelle Robinet asserts that Taoism is better understood as a way of life than as a religion, and that its adherents do not approach or view Taoism the way non-Taoist historians have done.[48] In the Tractate of Actions and their Retributions, a traditional teaching, spiritual immortality can be rewarded to people who do a certain amount of good deeds and live a simple, pure life. A list of good deeds and sins are tallied to determine whether or not a mortal is worthy. Spiritual immortality in this definition allows the soul to leave the earthly realms of afterlife and go to pure realms in the Taoist cosmology.[49]Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrians believe that on the fourth day after death, the human soul leaves the body and the body remains as an empty shell. Souls would go to either heaven or hell; these concepts of the afterlife in Zoroastrianism may have influenced Abrahamic religions. The Persian word for "immortal" is associated with the month "Amurdad", meaning "deathless" in Persian, in the Iranian calendar (near the end of July). The month of Amurdad or Ameretat is celebrated in Persian culture as ancient Persians believed the "Angel of Immortality" won over the "Angel of Death" in this month.[50]Philosophical arguments for the immortality of the soul

Alcmaeon of Croton

Alcmaeon of Croton argued that the soul is continuously and ceaselessly in motion. The exact form of his argument is unclear, but it appears to have influenced Plato, Aristotle, and other later writers.[51]Plato

Plato's Phaedo advances four arguments for the soul's immortality:[52]- The Cyclical Argument, or Opposites Argument explains that Forms are eternal and unchanging, and as the soul always brings life, then it must not die, and is necessarily "imperishable". As the body is mortal and is subject to physical death, the soul must be its indestructible opposite. Plato then suggests the analogy of fire and cold. If the form of cold is imperishable, and fire, its opposite, was within close proximity, it would have to withdraw intact as does the soul during death. This could be likened to the idea of the opposite charges of magnets.

- The Theory of Recollection explains that we possess some non-empirical knowledge (e.g. The Form of Equality) at birth, implying the soul existed before birth to carry that knowledge. Another account of the theory is found in Plato's Meno, although in that case Socrates implies anamnesis (previous knowledge of everything) whereas he is not so bold in Phaedo.

- The Affinity Argument, explains that invisible, immortal, and incorporeal things are different from visible, mortal, and corporeal things. Our soul is of the former, while our body is of the latter, so when our bodies die and decay, our soul will continue to live.

- The Argument from Form of Life, or The Final Argument explains that the Forms, incorporeal and static entities, are the cause of all things in the world, and all things participate in Forms. For example, beautiful things participate in the Form of Beauty; the number four participates in the Form of the Even, etc. The soul, by its very nature, participates in the Form of Life, which means the soul can never die.

Plotinus

Plotinus offers a version of the argument that Kant calls "The Achilles of Rationalist Psychology". Plotinus first argues that the soul is simple, then notes that a simple being cannot decompose. Many subsequent philosophers have argued both that the soul is simple and that it must be immortal. The tradition arguably culminates with Moses Mendelssohn's Phaedon.[53]Metochites

Theodore Metochites argues that part of the soul's nature is to move itself, but that a given movement will cease only if what causes the movement is separated from the thing moved – an impossibility if they are one and the same.[54]Avicenna

Avicenna argued for the distinctness of the soul and the body, and the incorruptibility of the former.[55]Aquinas

The full argument for the immortality of the soul and Thomas Aquinas' elaboration of Aristotelian theory is found in Question 75 of the First Part of the Summa Theologica.[56]Descartes

René Descartes endorses the claim that the soul is simple, and also that this entails that it cannot decompose. Descartes does not address the possibility that the soul might suddenly disappear.[57]Leibniz

In early work, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz endorses a version of the argument from the simplicity of the soul to its immortality, but like his predecessors, he does not address the possibility that the soul might suddenly disappear. In his monadology he advances a sophisticated novel argument for the immortality of monads.[58]Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn's Phaedon is a defense of the simplicity and immortality of the soul. It is a series of three dialogues, revisiting the Platonic dialogue Phaedo, in which Socrates argues for the immortality of the soul, in preparation for his own death. Many philosophers, including Plotinus, Descartes, and Leibniz, argue that the soul is simple, and that because simples cannot decompose they must be immortal. In the Phaedon, Mendelssohn addresses gaps in earlier versions of this argument (an argument that Kant calls the Achilles of Rationalist Psychology). The Phaedon contains an original argument for the simplicity of the soul, and also an original argument that simples cannot suddenly disappear. It contains further original arguments that the soul must retain its rational capacities as long as it exists.[59]Ethics

The possibility of clinical immortality raises a host of medical, philosophical, and religious issues and ethical questions. These include persistent vegetative states, the nature of personality over time, technology to mimic or copy the mind or its processes, social and economic disparities created by longevity, and survival of the heat death of the universe.Undesirability

Physical immortality has also been imagined as a form of eternal torment, as in Mary Shelley's short story "The Mortal Immortal", the protagonist of which witnesses everyone he cares about dying around him. Jorge Luis Borges explored the idea that life gets its meaning from death in the short story "The Immortal"; an entire society having achieved immortality, they found time becoming infinite, and so found no motivation for any action. In his book Thursday's Fictions, and the stage and film adaptations of it, Richard James Allen tells the story of a woman named Thursday who tries to cheat the cycle of reincarnation to get a form of eternal life. At the end of this fantastical tale, her son, Wednesday, who has witnessed the havoc his mother's quest has caused, forgoes the opportunity for immortality when it is offered to him.[60] Likewise, the novel Tuck Everlasting depicts immortality as "falling off the wheel of life" and is viewed as a curse as opposed to a blessing. In the anime Casshern Sins humanity achieves immortality due to advances in medical technology; however, the inability of the human race to die causes Luna, a Messianic figure, to come forth and offer normal lifespans because she believed that without death, humans could not live. Ultimately, Casshern takes up the cause of death for humanity when Luna begins to restore humanity's immortality. In Anne Rice's book series The Vampire Chronicles, vampires are portrayed as immortal and ageless, but their inability to cope with the changes in the world around them means that few vampires live for much more than a century, and those who do often view their changeless form as a curse.In his book Death, Yale philosopher Shelly Kagan argues that any form of human immortality would be undesirable. Kagan's argument takes the form of a dilemma. Either our characters remain essentially the same in an immortal afterlife, or they do not. If our characters remain basically the same—that is, if we retain more or less the desires, interests, and goals that we have now—then eventually, over an infinite stretch of time, we will get bored and find eternal life unbearably tedious. If, on the other hand, our characters are radically changed—e.g., by God periodically erasing our memories or giving us rat-like brains that never tire of certain simple pleasures—then such a person would be too different from our current self for us to care much what happens to them. Either way, Kagan argues, immortality is unattractive. The best outcome, Kagan argues, would be for humans to live as long as they desired and then to accept death gratefully as rescuing us from the unbearable tedium of immortality.[61]

Sociology

If human beings were to achieve immortality, there would most likely be a change in the worlds' social structures. Sociologist argue that human beings' awareness of their own mortality shapes their behavior.[62] With the advancements in medical technology in extending human life, there may need to be serious considerations made about future social structures. The world is already experiencing a global demographic shift of increasingly ageing populations with lower replacement rates.[63] The social changes that are made to accommodate this new population shift may be able to offer insight on the possibility of an immortal society.Politics

Although some scientists state that radical life extension, delaying and stopping aging are achievable,[64] there are no international or national programs focused on stopping aging or on radical life extension. In 2012 in Russia, and then in the United States, Israel and the Netherlands, pro-immortality political parties were launched. They aimed to provide political support to anti-aging and radical life extension research and technologies and at the same time transition to the next step, radical life extension, life without aging, and finally, immortality and aim to make possible access to such technologies to most currently living people.[65]Symbols

The ankh

There are numerous symbols representing immortality. The ankh is an Egyptian symbol of life that holds connotations of immortality when depicted in the hands of the gods and pharaohs, who were seen as having control over the journey of life. The Möbius strip in the shape of a trefoil knot is another symbol of immortality. Most symbolic representations of infinity or the life cycle are often used to represent immortality depending on the context they are placed in. Other examples include the Ouroboros, the Chinese fungus of longevity, the ten kanji, the phoenix, the peacock in Christianity,[66] and the colors amaranth (in Western culture) and peach (in Chinese culture).

Fiction

Immortality is a popular subject in fiction, as it explores humanity's deep-seated fears and comprehension of its own mortality. Immortal beings and species abound in fiction, especially fantasy fiction, and the meaning of "immortal" tends to vary. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the first literary works, is primarily a quest of a hero seeking to become immortal.[6]Some fictional beings are completely immortal (or very nearly so) in that they are immune to death by injury, disease and age. Sometimes such powerful immortals can only be killed by each other, as is the case with the Q from the Star Trek series. Even if something can't be killed, a common plot device involves putting an immortal being into a slumber or limbo, as is done with Morgoth in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Silmarillion and the Dreaming God of Pathways Into Darkness. Storytellers often make it a point to give weaknesses to even the most indestructible of beings. For instance, Superman is supposed to be invulnerable, yet his enemies were able to exploit his now-infamous weakness: Kryptonite. (See also Achilles' heel.)

Many fictitious species are said to be immortal if they cannot die of old age, even though they can be killed through other means, such as injury. Modern fantasy elves often exhibit this form of immortality. Other creatures, such as vampires and the immortals in the film Highlander, can only die from beheading. The classic and stereotypical vampire is typically slain by one of several very specific means, including a silver bullet (or piercing with other silver weapons), a stake through the heart (perhaps made of consecrated wood), or by exposing them to sunlight.