This source of all being is an Aeon, in which an inner being dwells, known as Ennoea (ἔννοια, "thought, intent"), Charis (χάρις, "grace") or Sige (σιγή, "silence"). The split perfect being conceives the second Aeon, Nous (Νους, "mind"), within itself. Complex hierarchies of Aeons are thus produced, sometimes to the number of thirty. These Aeons belong to a purely ideal, noumenal, intelligible, or supersensible world; they are immaterial, they are hypostatic ideas. Together with the source from which they emanate, they form Pleroma (πλήρωμα, "fullness"). The lowest regions of Pleroma are closest to darkness; that is, the physical world.

The transition from immaterial to material, from noumenal to sensible, is created by a flaw, passion, or sin in an Aeon. According to Basilides, it is a flaw in the last sonship; according to others the sin of the Great Archon, or Aeon-Creator, of the Universe; according to others it is the passion of the female Aeon Sophia, who emanates without her partner Aeon, resulting in the Demiurge (Δημιουργός), a creature that should never have been. This creature does not belong to Pleroma, and the One emanates two savior Aeons, Christ and the Holy Spirit, to save humanity from the Demiurge. Christ then took a human form (Jesus), to teach humanity how to achieve Gnosis. The ultimate end of all Gnosis is metanoia (μετάνοια), or repentance—undoing the sin of material existence and returning to Pleroma.

Aeons bear a number of similarities to Judaeo-Christian angels, including roles as servants and emanations of God, and existing as beings of light. In fact, certain Gnostic Angels, such as Armozel, are also Aeons. The Gnostic Gospel of Judas, found in 2006, purchased, held, and translated by the National Geographic Society, also mentions Aeons.

Valentinus

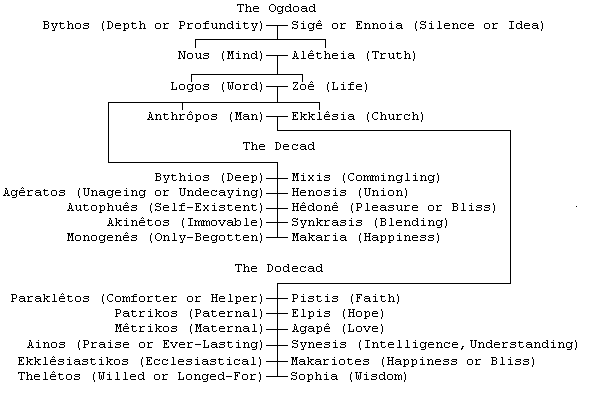

Valentinus assumed, as the beginning of all things, the Primal Being or Bythos, who after ages of silence and contemplation, gave rise to other beings by a process of emanation. The first series of beings, the Aeons, were thirty in number, representing fifteen syzygies or pairs sexually complementary. One common form is outlined below:

Tertullian's Against the Valentinians gives a slightly different sequence. The first eight of these Aeons, corresponding to generations one through four below, are referred to as the Ogdoad.

- First generation

- Bythos Βύθος (the One) and Sige Σιγή (Silence, Charis, Ennoea, etc.)

- Second generation

- Nous Νοΰς (Nus, Mind) and Aletheia Άλήθεια (Veritas, Truth)

- Third generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia

- Sermo (the Word; Logos Λόγος) and Vita (the Life; Zoe Ζωή)

- Fourth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita

- Anthropos Άνθρωπος (Homo, Man) and Ecclesia Έκκλησία

- Fifth generation

- Emanated from Sermo and Vita:

- Bythios (Profound) and Mixis (Mixture)

- Ageratos (Never old) and Henosis (Union)

- Autophyes (Essential nature) and Hedone (Pleasure)

- Acinetos (Immovable) and Syncrasis (Commixture)

- Monogenes (Only-begotten) and Macaria (Happiness)

- Emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia

- Paracletus (Comforter) and Pistis (Faith)

- Patricas (Paternal) and Elpis (Hope)

- Metricos (Maternal) and Agape (Love)

- Ainos (Praise) and Synesis (Intelligence)

- Ecclesiasticus (Son of Ecclesia) and Macariotes (Blessedness)

- Theletus (Perfect) and Sophia (Wisdom)

- Emanated from Sermo and Vita:

Ptolemy and Colorbasus

According to Irenaeus, the followers of the Gnostics Ptolemy and Colorbasus had Aeons that differ from those of Valentinus. Logos is created when Anthropos learns to speak. The first four are called the Tetrad, and the eight are the Ogdoad deities of the Ancient Egyptian pantheon.

- First generation

- Bythos Βύθος (the One) and Sige Σιγή (Silence, Charis, Ennoea, etc.)

- Second generation (conceived by the One):

- Ennoea (Thought) and Thelesis (Will)

- Third generation, emanated from Ennoea and Thelesis:

- Nous Νοΰς (or Monogenes) and Aletheia Άλήθεια

- Fourth generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia:

- Anthropos Άνθρωπος (Homo, Man) and Ecclesia Έκκλησία (see ref. 5 below)

- Fifth generation, emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia:

- Logos Λόγος and Zoe Ζωή

- Sixth generation:

- Emanated from Logos and Zoe:

- Bythius and Mixis

- Ageratos and Henosis

- Autophyes and Hedone

- Acinetos and Syncrasis

- Monogenes and Macaria

- Emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia:

- Paracletus and Pistis

- Patricos and Elpis

- Metricos and Agape

- Ainos and Synesis

- Ecclesiasticus and Macariotes

- Theletos and Sophia

- Emanated from Logos and Zoe:

The order of Anthropos and Ecclesia versus Logos and Zoe is somewhat debated; different sources give different accounts. Logos and Zoe are unique to this system as compared to the previous, and may be an evolved version of the first, totalling 32 Aeons, but it is not clear if the first two were actually regarded Aeons.

Modern interpretations

According to Myther, "The total number of Aeons, being 32, reflects the similarity of the mechanism to the Tree of Life, which, as suggested in the Zohar, incorporates 10 Sephiroth and 22 paths interconnecting these 10 Sephiroth; while 10 Aeons are created during the first five generations from which come the other 22 Aeons later during the sixth generation."

Sige

In the system of Valentinus, as expounded by Irenaeus (i. 1), the origin of things was traced to two eternal co-existent principles, a male and a female. The male was called Bythos or Proarche, or Propator, etc.; the female had the names Ennoea, Charis and Sige. The whole Aeonology of Valentinus was based on a theory of syzygies, or pairs of Aeons, each Aeon being provided with a consort; and the supposed need of the co-operation of a male and female principle for the generation of new ones, was common to Valentinus and some earlier Gnostic systems. But it was a disputed point in these systems whether the First Principle of all was thus twofold. There were those, both in earlier systems, and even among the Valentinians who held, that the origin of things was to be traced to a single Principle, which some described as hermaphrodite; others said was above all sex. And among the Valentinians who counted thirty Aeons, there were those who counted Bythos and Sige as the first pair; others who asserted the Single Principle excluded Bythos from the number, and made out the number of thirty without reckoning him. Thus Irenaeus says of the Valentinians (I. ii. 4. p. 10), "For they maintain that sometimes the Father acts in conjunction with Sige, but that at other times he shows himself independent both of male and female." And (I. xi. 5) "For some declare him to be without a consort, and neither male nor female, and, in fact, nothing at all; while others affirm him to be masculo-feminine, assigning to him the nature of a hermaphrodite; others, again, allot Sige to him as a spouse, that thus may be formed the first conjunction."

Hippolytus supposes Valentinus to have derived his system from that of Simon; and in that as expounded in the Apophasis Megale, from which he gives extracts, the origin of things is derived from six roots, divided into three pairs; but all these roots spring from a single independent Principle, which is without consort. The name Sige occurs in the description which Hippolytus (vi. 18) quotes from the Apophasis, how from the supreme Principle there arise the male and female offshoots nous and epinoia. The name Sige is there given not to either of the offshoots but to the supreme Principle itself: however, in the description, these offshoots appear less as distinct entities than as different aspects of the same Being.

Cyril of Jerusalem (Catech. vi. 17) makes Sige the daughter of Bythos and by him the mother of Logos, a fable which he classes with the incests which heathen mythology attributed to Jupiter. Irenaeus (II. xii.) ridicules the absurdity of the later form of Valentinian theory, in which Sige and Logos are represented as coexistent Aeons in the same Pleroma. "Where there is Silence" he says, "there will not be Word; and where there is Word, there cannot be Silence". He goes on (ii. 14) to trace the invention of Sige to the heathen poets, quoting Antiphanes, who in his Theogony makes Chaos the offspring of Night and Silence.

In place of Night and Silence they substitute Bythus and Sige; instead of Chaos, they put Nous; and for Love (by whom, says the comic poet, all other things were set in order) they have brought forward the Word; while for the primary and greatest gods they have formed the Æons; and in place of the secondary gods, they tell us of that creation by their mother which is outside of the Pleroma, calling it the second Ogdoad. ... these men call those things which are within the Pleroma real existences, just as those philosophers did the atoms; while they maintain that those which are without the Pleroma have no true existence, even as those did respecting the vacuum. They have thus banished themselves in this world (since they are here outside of the Pleroma) into a place which has no existence. Again, when they maintain that these things [below] are images of those which have a true existence [above], they again most manifestly rehearse the doctrine of Democritus and Plato. For Democritus was the first who maintained that numerous and diverse figures were stamped, as it were, with the forms [of things above], and descended from universal space into this world. But Plato, for his part, speaks of matter, and exemplar, and God. These men, following those distinctions, have styled what he calls ideas, and exemplar, the images of those things which are above ...

Ennoea

In the attempts made by the framers of different Gnostic systems to explain the origin of the existing world, the first stage in the process was usually made by personifying the conception in the divine mind of that which was to emanate from Him. We learn from Justin Martyr (Ap. I. 26), and from Irenaeus (I. 23), that the word Ennoea was used in a technical sense in the system of Simon. The Latin translation of Irenaeus either retains the word, or renders "mentis conceptio." Tertullian has "injectio" (De Anima, 34). In the Apophasis Megale cited by Hippolytus (Ref. vi. 18, 19, p. 174), the word used is not Ennoia but Epinoia. Irenaeus states (I. 23) that the word Ennoea passed from the system of Simon into that of Menander. In the Barbeliot system which Irenaeus also counts as derived from that of Simon (I. 29), Ennoea appears as one of the first in the series of emanations from the unnameable Father.

In the system of Valentinus (Iren. I. i.) Ennoea is one of several alternative names for the consort of the primary Aeon Bythos. For the somewhat different form in which Ptolemaeus presented this part of the system see Irenaeus (I. xii.). Irenaeus criticises this part of the system (II. xiii.). The name Ennoea is similarly used in the Ophite system described by Irenaeus (I. xxx.).

Charis

Charis, in the system of Valentinus, was an alternative name, with Ennoea and Sige, for the consort of the primary Aeon Bythos (Iren. i. 4). The name expresses that aspect of the absolute Greatness in which it is regarded not as a solitary monad, but as imparting from its perfection to beings of which it is the ultimate source; and this is the explanation given in the Valentinian fragment preserved by Epiphanius (Haer. xxxi. 6), dia to epikechoregekenai auten thesaurismata tou Megethous tois ek tou Megethous. The use of the word Charis enabled Ptolemaeus (quoted by Irenaeus, i. 8) to find in John 1:14 the first tetrad of Aeons, viz., Pater, Monogenes, Charis, Aletheia. The suspicion arises that it was with a view to such an identification that names to be found in the prologue of St. John's Gospel were added as alternative appellations to the original names of the Aeons. But this is a point on which we have no data to pronounce. Charis has an important place in the system of Marcus (Irenaeus, i. 13). The name Charis appears also in the system of the Barbelitae (Irenaeus, i. 29), but as denoting a later emanation than in the Valentinian system. The word has possibly also a technical meaning in the Ophite prayers preserved by Origen (Contra Celsum, vi. 31), all of which end with the invocation he charis synesto moi, nai pater, synesto.

Nous

Ecclesia

This higher Ecclesia was held to be the archetype of the lower Ecclesia constituted by the spiritual seed on earth (Iren. I. v. 6, p. 28). In a Gnostic system described by Irenaeus (I. xxx. p. 109) we have also a heavenly church, not, however, as a separate Aeon, but as constituted by the harmony of the first existing beings. According to Hippolytus (v. 6, p. 95), the Naassenes counted three Ecclesiae.

It is especially in the case of the church that we find in Christian speculation prior to Valentinus traces of the conception, which lies at the root of the whole doctrine of Aeons, that earthly things have their archetypes in preexistent heavenly things. Hermas (Vis. ii. 4) speaks of the church as created before all things and of the world as formed for her sake; and in the newly discovered portion of the so-called Second Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians (c. 14) the writer speaks of the spiritual church as created before the sun and moon, as pre-existent like Christ Himself, and like him manifested in the last days for men's salvation; and he even uses language which, if it were not sufficiently accounted for by what is said in the Epistle to the Ephesians as to the union between Christ and His church, might be supposed to have affinity with the Valentinian doctrine of the relation between Anthropos and Ecclesia.

The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews quotes the direction to Moses to make the tabernacle after the pattern shewn him on the Mount (a passage cited in Acts 7:44), and his argument dwells on the inference that the various parts of the Jewish service were but copies of better heavenly archetypes. This same heavenly tabernacle appears as part of the imagery of the book of the Revelation (11:19, 15:5). In the same book the church appears as the Lamb's wife, the new Jerusalem descending from heaven; and St. Paul's teaching (Ephesians 1:3) might be thrown into the form that the church existed in God's election before the foundation of the world.

Anthropos

As the world is an image of the living Aeon (tou zontos aionos), so is man an image of the pre-existent man of the anthrops proon. Valentinus, according to Clemens Alexandrinus (Valentini homil. ap. Clem. Strom. iv. 13, 92), spoke of the Sophia as an artist (zographos) making this visible lower world a picture of the glorious Archetype, but the hearer or reader would as readily understand the heavenly wisdom of the Book of Proverbs to be meant by this Sophia, as the 12th and fallen Aeon. Under her (according to Valentinus) stand the world-creative angels, whose head is the Demiurge. Her formation (plasma) is Adam created in the name of the Anthropos proon. In him thus made a higher power puts the seed of the heavenly pneumatic essence (sperma tes anothen ousias). Thus furnished with higher insight, Adam excites the fears of the angels; for even as kosmikoi anthropoi are seized with fear of the images made by their own hands to bear the name of God, i.e. the idols, so these angels cause the images they have made to disappear (Ep. ad amicos ap. Clem. Alex. Strom. ii. 8, 36).

... they say that Achamoth sketched these pictures in honor of the aeons. Yet they transfer this work to Soter as its originator who operated through Achamoth so as to present her as the very image of the invisible and unknown Father, she being invisible, of course, and unknown to the Demiurge, and in the same way he created this same Demiurge to correspond to Nus, the son. The Archangels, creations of the Demiurge, are models of the rest of the aeons. ... don't you agree that I should laugh at these pictures painted by such a lunatic painter? Achamoth, a female and yet the image of the Father; the Demiurge, ignorant of his mother—not to mention of his Father—yet representing Nus who is not ignorant of his Father; the angels, the reproductions of their masters. This is the same as counterfeiting a fake ...

— Tertullian, Against the Valentinians, XIX

Horos

According to the doctrine of Valentinus, as described by Irenaeus i. 2, the youngest Aeon Sophia, in her passion to comprehend the Father of all, runs the danger of being absorbed into his essence, from which she is saved by coming into contact with the limiting power Horos, whose function it is to strengthen all things outside the ineffable Greatness, by confining each to its appointed place. According to this version Horos was a previously existing power; but according to another, and apparently a later account, Horos is an Aeon only generated on this occasion at the request of all the Aeons, who implored the Father to avert a danger that threatened to affect them all. Then (as Hippolytus tells the story, vi. 31) he directs the production of a new pair of Aeons, Christ and the Holy Spirit, who restore order by separating from the Pleroma the unformed offspring of Sophia. After this Horos is produced in order to secure the permanence of the order thus produced. Irenaeus (u. s.) reverses this order, and Horos is produced first, afterwards the other pair.

The Valentinian fragment in Epiphanius (Haer. 31, p. 171), which seems to give a more ancient form of this heresy, knows nothing of Horos, but it relates as the last spiritual birth the generation of five beings without consorts, whose names are used in the Irenaean version as titles for the supernumerary Aeon Horos. But besides, this Aeon has a sixth name, which in the version of Hippolytus is made his primary title Stauros; and it is explained (Irenaeus, i. 3) that besides his function as a separator, in respect of which he is called Horos, this Aeon does the work of stablishing and settling, in respect of which he is called Stauros. A derivation from sterizo is hinted at.

The literal earthly crucifixion of the Saviour (that seen by the psychic church, which only believes in the historical Jesus) was meant to represent an archetypal scene in the world of Aeons, when the younger Sophia, Achamoth, is healed through the Savior's instrumentation.

The animal and carnal Christ, however, does suffer after the fashion of the superior Christ, who, for the purpose of producing Achamoth, had been stretched upon the cross, that is, Horos, in a substantial though not a cognizable form. In this manner do they reduce all things to mere images—Christians themselves being indeed nothing but imaginary beings!

— Tertullian, Against the Valentinians, XXVII

The distinction just explained as to the different use of the names Horos and Stauros was not carefully observed by Valentinians. Thus the last word is sometimes used when the function of separation and division is spoken of (Excerpt. ex Script. Theodot. 22 and 42, Clem. Alex. ii. pp. 974, 979), it being remarked in the latter passage that the cross separates the faithful from the unbelievers; and Clem. Alex., who occasionally uses Valentinian language in an orthodox sense, speaks in the same way (Paed. iii. 12, p. 303, and Strom. ii. 20, p. 486).

In the Valentinian theory there is a double Horos, or at least a double function discharged by Horos.

Plato, then, in expounding mysteries concerning the universe, writes to Dionysius expressing himself after some such manner as this: “. . . All things are about the King of all, and on his account are all things, and he is cause of all the glorious (objects of creation). The second is about the second, and the third about the third. But pertaining to the King there is none of those things of which I have spoken. But after this the soul earnestly desires to learn what sort these are, looking upon those things that are akin to itself, and not one of these is (in itself) sufficient. . . .”

Valentinus, falling in with these (remarks), has made a fundamental principle in his system “the King of all,” whom Plato mentioned, and whom this heretic styles Pater, and Bythos, and Proarche over the rest of the Æons. And when Plato uses the words, “what is second about things that are second,” Valentinus supposes to be second all the Æons that are within the limit [Horos] (of the Pleroma, as well as) the limit (itself). And when Plato uses the words, “what is third about what is third,” he has (constituted as third) the entire of the arrangement (existing) outside the limit and the Pleroma.— Hippolytus, Philosophumena, VI, 32

On the one hand, he discharges as already described, a function within the Pleroma, separating the other Aeons from the ineffable Bythos, and saving them from absorption into his essence. On the other hand, Horos is the outside boundary of the Pleroma itself, giving it permanence and stability by guarding it against the intrusion of any foreign element.

Cultural references

The animated TV series Æon Flux draws its name and some of its iconography from Gnosticism, notably aeons (the two main characters forming a syzygy) and a demiurge.

The webcomic Homestuck also draws inspiration from Gnostic ideas, with the main character Jade Harley being called "gardenGnostic" as a pseudonym. She also fuses with her dog, Becquerel, forming a syzygy. Yaldabaoth and Abraxas also appear in the comic.

The video game "Cruelty Squad" has multiple mentions and nods to the Gnostic mythology. The targets of the level "Office" are four sub archons. The level after it, aptly named "Archon Grid" has its final boss as Abraxas, although he is contorted to look much different, holding certain characteristics in common. There are many other references to Gnostic ideologies, such as the main goal of the game achieving ultimate enlightenment over everything else, rather than accepting your situation.