From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

fundamental theorem of calculus is a

theorem that links the concept of

differentiating a

function with the concept of

integrating a function.

The first part of the theorem, sometimes called the

first fundamental theorem of calculus, states that one of the

antiderivatives (also called

indefinite integral), say

F, of some function

f may be obtained as the integral of

f with a variable bound of integration. This implies the existence of

antiderivatives for

continuous functions.

Conversely, the second part of the theorem, sometimes called the

second fundamental theorem of calculus, states that the integral of a function

f over some interval can be computed by using any one, say

F, of its infinitely many

antiderivatives. This part of the theorem has key practical applications, because explicitly finding the antiderivative of a function by

symbolic integration avoids

numerical integration to compute integrals. This provides generally a better numerical accuracy.

History

The fundamental theorem of calculus relates differentiation and

integration, showing that these two operations are essentially inverses

of one another. Before the discovery of this theorem, it was not

recognized that these two operations were related. Ancient

Greek mathematicians knew how to compute area via

infinitesimals, an operation that we would now call

integration. The origins of

differentiation

likewise predate the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus by hundreds of

years; for example, in the fourteenth century the notions of

continuity of functions and

motion were studied by the

Oxford Calculators

and other scholars. The historical relevance of the Fundamental Theorem

of Calculus is not the ability to calculate these operations, but the

realization that the two seemingly distinct operations (calculation of

geometric areas, and calculation of velocities) are actually closely

related.

The first published statement and proof of a rudimentary form of the fundamental theorem, strongly geometric in character, was by

James Gregory (1638–1675).

Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) proved a more generalized version of the theorem, while his student

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) completed the development of the surrounding mathematical theory.

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) systematized the knowledge into a calculus for infinitesimal quantities and introduced the notation used today.

Geometric meaning

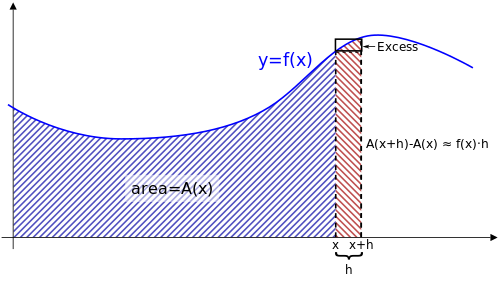

The area shaded in red stripes can be estimated as h times f(x).

Alternatively, if the function A(x) were known, it could be

computed exactly as A(x + h) − A(x). These two values are

approximately equal, particularly for small h.

For a continuous function

y = f(x) whose graph is plotted as a curve, each value of

x has a corresponding area function

A(

x), representing the area beneath the curve between 0 and

x. The function

A(

x) may not be known, but it is given that it represents the area under the curve.

The area under the curve between

x and

x + h could be computed by finding the area between 0 and

x + h, then subtracting the area between 0 and

x. In other words, the area of this “strip” would be

A(x + h) − A(x).

There is another way to

estimate the area of this same strip. As shown in the accompanying figure,

h is multiplied by

f(

x) to find the area of a rectangle that is approximately the same size as this strip. So:

In fact, this estimate becomes a perfect equality if we add the red portion of the "excess" area shown in the diagram. So:

Rearranging terms:

.

.

As

h approaches 0 in the

limit, the last fraction can be shown to go to zero.

This is true because the area of the red portion of excess region is

less than or equal to the area of the tiny black-bordered rectangle.

More precisely,

By the continuity of

f, the latter expression tends to zero as

h does. Therefore, the left-hand side tends to zero as

h does, which implies

This implies

f(x) = A′(x). That is, the derivative of the area function

A(

x) exists and is the original function

f(

x); so, the area function is simply an

antiderivative

of the original function. Computing the derivative of a function and

“finding the area” under its curve are "opposite" operations. This is

the crux of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

Physical intuition

Intuitively, the theorem simply states that the sum of

infinitesimal changes in a quantity over time (or over some other variable) adds up to the net change in the quantity.

Imagine for example using a stopwatch to mark-off tiny increments

of time as a car travels down a highway. Imagine also looking at the

car's speedometer as it travels, so that at every moment you know the

velocity of the car. To understand the power of this theorem, imagine

also that you are not allowed to look out the window of the car, so that

you have no direct evidence of how far the car has traveled.

For any tiny interval of time in the car, you could calculate how

far the car has traveled in that interval by multiplying the current

speed of the car times the length of that tiny interval of time. (This

is because

distance =

speed  time

time.)

Now imagine doing this instant after instant, so that for every

tiny interval of time you know how far the car has traveled. In

principle, you could then calculate the

total distance traveled in the car (even though you've never looked out the window) by simply summing-up all those tiny distances.

- distance traveled =

the velocity at any instant

the velocity at any instant  a tiny interval of time

a tiny interval of time

In other words,

- distance traveled =

On the right hand side of this equation, as

becomes infinitesimally small, the operation of "summing up" corresponds to

integration. So what we've shown is that the integral of the velocity function can be used to compute how far the car has traveled.

Now remember that the velocity function is simply the derivative

of the position function. So what we have really shown is that

integrating the velocity simply recovers the original position function. This is the basic idea of the theorem: that

integration and

differentiation are closely related operations, each essentially being the inverse of the other.

In other words, in terms of one's physical intuition, the theorem

simply states that the sum of the changes in a quantity over time (such

as

position, as calculated by multiplying

velocity times

time) adds up to the total net change in the quantity. Or to put this more generally:

- Given a quantity

that changes over some variable

that changes over some variable  , and

, and

- Given the velocity

with which that quantity changes over that variable

with which that quantity changes over that variable

then the idea that "distance equals speed times time" corresponds to the statement

meaning that one can recover the original function

by integrating its derivative, the velocity

, over

.

Formal statements

There are two parts to the theorem. The first part deals with the derivative of an

antiderivative, while the second part deals with the relationship between antiderivatives and

definite integrals.

First part

This part is sometimes referred to as the

first fundamental theorem of calculus.

Let

f be a continuous real-valued function defined on a

closed interval [

a,

b]. Let

F be the function defined, for all

x in [

a,

b], by

Then,

F is uniformly continuous on [

a,

b], differentiable on the open interval

(a, b), and

for all

x in (

a,

b).

Corollary

Fundamental theorem of calculus (animation)

The fundamental theorem is often employed to compute the definite integral of a function

for which an antiderivative

is known. Specifically, if

is a real-valued continuous function on

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

and

is an antiderivative of

in

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

then

The corollary assumes

continuity on the whole interval. This result is strengthened slightly in the following part of the theorem.

Second part

This part is sometimes referred to as the second fundamental theorem of calculus

[8] or the

Newton–Leibniz axiom.

Let

be a real-valued function on a

closed interval ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

and

an antiderivative of

in

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

:

If

is

Riemann integrable on

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

then

The second part is somewhat stronger than the corollary because it does not assume that

is continuous.

When an antiderivative

exists, then there are infinitely many antiderivatives for

, obtained by adding an arbitrary constant to

. Also, by the first part of the theorem, antiderivatives of

always exist when

is continuous.

Proof of the first part

For a given

f(

t), define the function

F(

x) as

For any two numbers

x1 and

x1 + Δ

x in [

a,

b], we have

and

Subtracting the two equalities gives

It can be shown that

- (The sum of the areas of two adjacent regions is equal to the area of both regions combined.)

Manipulating this equation gives

Substituting the above into (1) results in

According to the

mean value theorem for integration, there exists a real number

![{\displaystyle c\in [x_{1},x_{1}+\Delta x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/734554629a2c09f13968c19d7bc12548de243fa2)

such that

To keep the notation simple, we write just

, but one should keep in mind that, for a given function

, the value of

depends on

and on

but is always confined to the interval

![{\displaystyle [x_{1},x_{1}+\Delta x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd3360df1299dc75d795101fbbe129ae7f39d82b)

. Substituting the above into (2) we get

Dividing both sides by

gives

- The expression on the left side of the equation is Newton's difference quotient for F at x1.

Take the limit as

→ 0 on both sides of the equation.

The expression on the left side of the equation is the definition of the derivative of

F at

x1.

To find the other limit, we use the

squeeze theorem. The number

c is in the interval [

x1,

x1 + Δ

x], so

x1 ≤

c ≤

x1 + Δ

x.

Also,

and

Therefore, according to the squeeze theorem,

Substituting into (3), we get

The function

f is continuous at

c, so the limit can be taken inside the function. Therefore, we get

which completes the proof.

Proof of the corollary

Suppose

F is an antiderivative of

f, with

f continuous on

[a, b]. Let

.

.

By the

first part of the theorem, we know

G is also an antiderivative of

f. Since

F' - G' = 0 the mean value theorem implies that

F - G is a constant function, i. e. there is a number

c such that

G(x) = F(x) + c, for all

x in

[a, b]. Letting

x = a, we have

which means

c = − F(a). In other words,

G(x) = F(x) − F(a), and so

Proof of the second part

This is a limit proof by

Riemann sums.

Let

f be (Riemann) integrable on the interval

[a, b], and let

f admit an antiderivative

F on

[a, b]. Begin with the quantity

F(b) − F(a). Let there be numbers

x1, ...,

xn

such that

It follows that

Now, we add each

F(

xi) along with its additive inverse, so that the resulting quantity is equal:

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}F(b)-F(a)&=F(x_{n})+[-F(x_{n-1})+F(x_{n-1})]+\cdots +[-F(x_{1})+F(x_{1})]-F(x_{0})\\&=[F(x_{n})-F(x_{n-1})]+[F(x_{n-1})-F(x_{n-2})]+\cdots +[F(x_{2})-F(x_{1})]+[F(x_{1})-F(x_{0})].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0ed73983d4fe8b367d8390456fde88b3751cf868)

The above quantity can be written as the following sum:

![F(b)-F(a)=\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[F(x_{i})-F(x_{i-1})].\qquad (1)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/96218220560d2818abb201d877e1c5584571f3d3)

Next, we employ the

mean value theorem. Stated briefly, let

F be continuous on the closed interval [

a,

b] and differentiable on the open interval (

a,

b). Then there exists some

c in (

a,

b) such that

It follows that

The function

F is differentiable on the interval

[a, b]; therefore, it is also differentiable and continuous on each interval

[xi−1, xi]. According to the mean value theorem (above),

Substituting the above into (1), we get

![F(b)-F(a)=\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[F'(c_{i})(x_{i}-x_{i-1})].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/42a36438ec654418302333f8a6af2ad0a801a802)

The assumption implies

Also,

can be expressed as

of partition

.

![F(b)-F(a)=\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[f(c_{i})(\Delta x_{i})].\qquad (2)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a63b98427f0819723c18ed610a9710051d63832e)

A

converging sequence of Riemann sums. The number in the

upper left is

the total area of the blue rectangles. They converge

to the definite

integral of the function.

We are describing the area of a rectangle, with the width times the

height, and we are adding the areas together. Each rectangle, by virtue

of the

mean value theorem, describes an approximation of the curve section it is drawn over. Also

need not be the same for all values of

i, or in other words that the width of the rectangles can differ. What we have to do is approximate the curve with

n rectangles. Now, as the size of the partitions get smaller and

n increases, resulting in more partitions to cover the space, we get closer and closer to the actual area of the curve.

By taking the limit of the expression as the norm of the partitions approaches zero, we arrive at the

Riemann integral. We know that this limit exists because

f

was assumed to be integrable. That is, we take the limit as the largest

of the partitions approaches zero in size, so that all other partitions

are smaller and the number of partitions approaches infinity.

So, we take the limit on both sides of (2). This gives us

![\lim _{\|\Delta x_{i}\|\to 0}F(b)-F(a)=\lim _{\|\Delta x_{i}\|\to 0}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[f(c_{i})(\Delta x_{i})].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/77c47474aa4834116cd8a4d3bf9c4e6375fd546c)

Neither

F(

b) nor

F(

a) is dependent on

, so the limit on the left side remains

F(b) − F(a).

![F(b)-F(a)=\lim _{\|\Delta x_{i}\|\to 0}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[f(c_{i})(\Delta x_{i})].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/06834f239d819540b77838929cf53a31dcae0648)

The expression on the right side of the equation defines the integral over

f from

a to

b. Therefore, we obtain

which completes the proof.

It almost looks like the first part of the theorem follows directly from the second. That is, suppose

G is an antiderivative of

f. Then by the second theorem,

. Now, suppose

. Then

F has the same derivative as

G, and therefore

F′ = f. This argument only works, however, if we already know that

f

has an antiderivative, and the only way we know that all continuous

functions have antiderivatives is by the first part of the Fundamental

Theorem.

For example, if

f(x) = e−x2, then

f has an antiderivative, namely

and there is no simpler expression for this function. It is

therefore important not to interpret the second part of the theorem as

the definition of the integral. Indeed, there are many functions that

are integrable but lack elementary antiderivatives, and discontinuous

functions can be integrable but lack any antiderivatives at all.

Conversely, many functions that have antiderivatives are not Riemann

integrable.

Examples

As an example, suppose the following is to be calculated:

Here,

and we can use

as the antiderivative. Therefore:

Or, more generally, suppose that

is to be calculated. Here,

and

can be used as the antiderivative. Therefore:

Or, equivalently,

As a theoretical example, the theorem can be used to prove that

Since,

the result follows from,

Generalizations

We don't need to assume continuity of

f on the whole interval. Part I of the theorem then says: if

f is any

Lebesgue integrable function on

[a, b] and

x0 is a number in

[a, b] such that

f is continuous at

x0, then

is differentiable for

x = x0 with

F′(x0) = f(x0). We can relax the conditions on

f still further and suppose that it is merely locally integrable. In that case, we can conclude that the function

F is differentiable

almost everywhere and

F′(x) = f(x) almost everywhere. On the real line this statement is equivalent to

Lebesgue's differentiation theorem. These results remain true for the Henstock–Kurzweil integral, which allows a larger class of integrable functions (

Bartle 2001, Thm. 4.11).

In higher dimensions Lebesgue's differentiation theorem

generalizes the Fundamental theorem of calculus by stating that for

almost every

x, the average value of a function

f over a ball of radius

r centered at

x tends to

f(

x) as

r tends to 0.

Part II of the theorem is true for any Lebesgue integrable function

f, which has an antiderivative

F (not all integrable functions do, though). In other words, if a real function

F on

[a, b] admits a derivative

f(

x) at

every point

x of

[a, b] and if this derivative

f is Lebesgue integrable on

[a, b], then

This result may fail for continuous functions

F that admit a derivative

f(

x) at almost every point

x, as the example of the

Cantor function shows. However, if

F is

absolutely continuous, it admits a derivative

F′(

x) at almost every point

x, and moreover

F′ is integrable, with

F(b) − F(a) equal to the integral of

F′ on

[a, b]. Conversely, if

f is any integrable function, then

F as given in the first formula will be absolutely continuous with

F′ =

f a.e.

The conditions of this theorem may again be relaxed by considering the integrals involved as

Henstock–Kurzweil integrals. Specifically, if a continuous function

F(

x) admits a derivative

f(

x) at all but countably many points, then

f(

x) is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable and

F(b) − F(a) is equal to the integral of

f on

[a, b]. The difference here is that the integrability of

f does not need to be assumed. (

Bartle 2001, Thm. 4.7)

The version of

Taylor's theorem, which expresses the error term as an integral, can be seen as a generalization of the fundamental theorem.

There is a version of the theorem for

complex functions: suppose

U is an open set in

C and

f : U → C is a function that has a

holomorphic antiderivative

F on

U. Then for every curve

γ : [a, b] → U, the

curve integral can be computed as

The fundamental theorem can be generalized to curve and surface integrals in higher dimensions and on

manifolds. One such generalization offered by the

calculus of moving surfaces is the

time evolution of integrals. The most familiar extensions of the fundamental theorem of calculus in higher dimensions are the

divergence theorem and the

gradient theorem.

One of the most powerful generalizations in this direction is

Stokes' theorem (sometimes known as the fundamental theorem of multivariable calculus): Let

M be an oriented

piecewise smooth manifold of

dimension n and let

be a smooth

compactly supported (n–1)-form on

M. If ∂

M denotes the

boundary of

M given its induced

orientation, then

Here

d is the

exterior derivative, which is defined using the manifold structure only.

The theorem is often used in situations where

M is an embedded oriented submanifold of some bigger manifold (e.g.

Rk) on which the form

is defined.

.

time.)

time.)the velocity at any instant

a tiny interval of time

becomes infinitesimally small, the operation of "summing up" corresponds to integration. So what we've shown is that the integral of the velocity function can be used to compute how far the car has traveled.

becomes infinitesimally small, the operation of "summing up" corresponds to integration. So what we've shown is that the integral of the velocity function can be used to compute how far the car has traveled.that changes over some variable

, and

with which that quantity changes over that variable

by integrating its derivative, the velocity

by integrating its derivative, the velocity  , over

, over  .

.

for which an antiderivative

for which an antiderivative  is known. Specifically, if

is known. Specifically, if  is a real-valued continuous function on

is a real-valued continuous function on ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) and

and  is an antiderivative of

is an antiderivative of  in

in ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) then

then

be a real-valued function on a closed interval

be a real-valued function on a closed interval ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) and

and  an antiderivative of

an antiderivative of  in

in ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) :

:

is Riemann integrable on

is Riemann integrable on ![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935) then

then

is continuous.

is continuous. exists, then there are infinitely many antiderivatives for

exists, then there are infinitely many antiderivatives for  , obtained by adding an arbitrary constant to

, obtained by adding an arbitrary constant to  . Also, by the first part of the theorem, antiderivatives of

. Also, by the first part of the theorem, antiderivatives of  always exist when

always exist when  is continuous.

is continuous.

![{\displaystyle c\in [x_{1},x_{1}+\Delta x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/734554629a2c09f13968c19d7bc12548de243fa2) such that

such that

, but one should keep in mind that, for a given function

, but one should keep in mind that, for a given function  , the value of

, the value of  depends on

depends on  and on

and on  but is always confined to the interval

but is always confined to the interval ![{\displaystyle [x_{1},x_{1}+\Delta x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd3360df1299dc75d795101fbbe129ae7f39d82b) . Substituting the above into (2) we get

. Substituting the above into (2) we get

gives

gives

→ 0 on both sides of the equation.

→ 0 on both sides of the equation.

and

and

.

Also,

Also,  can be expressed as

can be expressed as  of partition

of partition  .

.

need not be the same for all values of i, or in other words that the width of the rectangles can differ. What we have to do is approximate the curve with n rectangles. Now, as the size of the partitions get smaller and n increases, resulting in more partitions to cover the space, we get closer and closer to the actual area of the curve.

need not be the same for all values of i, or in other words that the width of the rectangles can differ. What we have to do is approximate the curve with n rectangles. Now, as the size of the partitions get smaller and n increases, resulting in more partitions to cover the space, we get closer and closer to the actual area of the curve. , so the limit on the left side remains F(b) − F(a).

, so the limit on the left side remains F(b) − F(a).

. Now, suppose

. Now, suppose  . Then F has the same derivative as G, and therefore F′ = f. This argument only works, however, if we already know that f

has an antiderivative, and the only way we know that all continuous

functions have antiderivatives is by the first part of the Fundamental

Theorem.

For example, if f(x) = e−x2, then f has an antiderivative, namely

. Then F has the same derivative as G, and therefore F′ = f. This argument only works, however, if we already know that f

has an antiderivative, and the only way we know that all continuous

functions have antiderivatives is by the first part of the Fundamental

Theorem.

For example, if f(x) = e−x2, then f has an antiderivative, namely

and we can use

and we can use  as the antiderivative. Therefore:

as the antiderivative. Therefore:

and

and  can be used as the antiderivative. Therefore:

can be used as the antiderivative. Therefore:

be a smooth compactly supported (n–1)-form on M. If ∂M denotes the boundary of M given its induced orientation, then

be a smooth compactly supported (n–1)-form on M. If ∂M denotes the boundary of M given its induced orientation, then

is defined.

is defined.

![F(b)-F(a)=\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[F'(c_{i})(x_{i}-x_{i-1})].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/42a36438ec654418302333f8a6af2ad0a801a802)

![F(b)-F(a)=\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[f(c_{i})(\Delta x_{i})].\qquad (2)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a63b98427f0819723c18ed610a9710051d63832e)

![F(b)-F(a)=\lim _{\|\Delta x_{i}\|\to 0}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\,[f(c_{i})(\Delta x_{i})].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/06834f239d819540b77838929cf53a31dcae0648)