Oligonucleotide synthesis is the chemical synthesis of relatively short fragments of nucleic acids with defined chemical structure (sequence). The technique is extremely useful in current laboratory practice because it provides a rapid and inexpensive access to custom-made oligonucleotides of the desired sequence. Whereas enzymes synthesize DNA and RNA only in a 5' to 3' direction, chemical oligonucleotide synthesis does not have this limitation, although it is, most often, carried out in the opposite, 3' to 5' direction. Currently, the process is implemented as solid-phase synthesis using phosphoramidite method and phosphoramidite building blocks derived from protected 2'-deoxynucleosides (dA, dC, dG, and T), ribonucleosides (A, C, G, and U), or chemically modified nucleosides, e.g. LNA or BNA.

To obtain the desired oligonucleotide, the building blocks are sequentially coupled to the growing oligonucleotide chain in the order required by the sequence of the product (see Synthetic cycle below). The process has been fully automated since the late 1970s. Upon the completion of the chain assembly, the product is released from the solid phase to solution, deprotected, and collected. The occurrence of side reactions sets practical limits for the length of synthetic oligonucleotides (up to about 200 nucleotide residues) because the number of errors accumulates with the length of the oligonucleotide being synthesized.[1] Products are often isolated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to obtain the desired oligonucleotides in high purity. Typically, synthetic oligonucleotides are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules around 15–25 bases in length.

Oligonucleotides find a variety of applications in molecular biology and medicine. They are most commonly used as antisense oligonucleotides, small interfering RNA, primers for DNA sequencing and amplification, probes for detecting complementary DNA or RNA via molecular hybridization, tools for the targeted introduction of mutations and restriction sites, and for the synthesis of artificial genes.

History

Early work and contemporary H-phosphonate synthesis

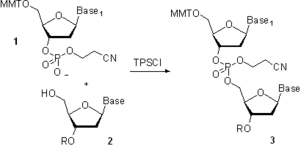

Scheme. 1. i: N-Chlorosuccinimide; Bn = -CH2Ph

In the early 1950s, Alexander Todd’s group pioneered H-phosphonate and phosphate triester methods of oligonucleotide synthesis. The reaction of compounds 1 and 2 to form H-phosphonate diester 3 is an H-phosphonate coupling in solution while that of compounds 4 and 5 to give 6 is a phosphotriester coupling (see phosphotriester synthesis below).

Scheme 2. Oligonucleotide sythesis by the H-Phosphonate Method

Thirty years later, this work inspired, independently, two research groups to adopt the H-phosphonate chemistry to the solid-phase synthesis using nucleoside H-phosphonate monoesters 7 as building blocks and pivaloyl chloride, 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (TPS-Cl), and other compounds as activators. The practical implementation of H-phosphonate method resulted in a very short and simple synthetic cycle consisting of only two steps, detritylation and coupling (Scheme 2). Oxidation of internucleosidic H-phosphonate diester linkages in 8 to phosphodiester linkages in 9 with a solution of iodine in aqueous pyridine is carried out at the end of the chain assembly rather than as a step in the synthetic cycle. If desired, the oxidation may be carried out under anhydrous conditions. Alternatively, 8 can be converted to phosphorothioate 10 or phosphoroselenoate 11 (X = Se), or oxidized by CCl4 in the presence of primary or secondary amines to phosphoramidate analogs 12. The method is very convenient in that various types of phosphate modifications (phosphate/phosphorothioate/phosphoramidate) may be introduced to the same oligonucleotide for modulation of its properties.

Most often, H-phosphonate building blocks are protected at the 5'-hydroxy group and at the amino group of nucleic bases A, C, and G in the same manner as phosphoramidite building blocks (see below). However, protection at the amino group is not mandatory.

Phosphodiester synthesis

Scheme. 3 Oligonucleotide coupling by phosphodiester method; Tr = -CPh3

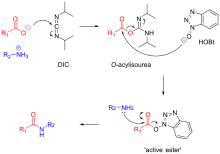

In the 1950s, Har Gobind Khorana and co-workers developed a phosphodiester method where 3’-O-acetylnucleoside-5’-O-phosphate 2 (Scheme 3) was activated with N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) or 4-toluenesulfonyl chloride (Ts-Cl). The activated species were reacted with a 5’-O-protected nucleoside 1 to give a protected dinucleoside monophosphate 3. Upon the removal of 3’-O-acetyl group using base-catalyzed hydrolysis, further chain elongation was carried out. Following this methodology, sets of tri- and tetradeoxyribonucleotides were synthesized and were enzymatically converted to longer oligonucleotides, which allowed elucidation of the genetic code. The major limitation of the phosphodiester method consisted in the formation of pyrophosphate oligomers and oligonucleotides branched at the internucleosidic phosphate. The method seems to be a step back from the more selective chemistry described earlier; however, at that time, most phosphate-protecting groups available now had not yet been introduced. The lack of the convenient protection strategy necessitated taking a retreat to a slower and less selective chemistry to achieve the ultimate goal of the study.

Phosphotriester synthesis

Scheme 4. Oligonucleotide coupling by phosphotriester method; MMT = -CPh2(4-MeOC6H4).

In the 1960s, groups led by R. Letsinger and C. Reese developed a phosphotriester approach. The defining difference from the phosphodiester approach was the protection of the phosphate moiety in the building block 1 (Scheme 4) and in the product 3 with 2-cyanoethyl group. This precluded the formation of oligonucleotides branched at the internucleosidic phosphate. The higher selectivity of the method allowed the use of more efficient coupling agents and catalysts, which dramatically reduced the length of the synthesis. The method, initially developed for the solution-phase synthesis, was also implemented on low-cross-linked "popcorn" polystyrene, and later on controlled pore glass (CPG, see "Solid support material" below), which initiated a massive research effort in solid-phase synthesis of oligonucleotides and eventually led to the automation of the oligonucleotide chain assembly.

Phosphite triester synthesis

In the 1970s, substantially more reactive P(III) derivatives of nucleosides, 3'-O-chlorophosphites, were successfully used for the formation of internucleosidic linkages. This led to the discovery of the phosphite triester methodology. The group led by M. Caruthers took the advantage of less aggressive and more selective 1H-tetrazolidophosphites and implemented the method on solid phase. Very shortly after, the workers from the same group further improved the method by using more stable nucleoside phosphoramidites as building blocks. The use of 2-cyanoethyl phosphite-protecting group in place of a less user-friendly methyl group led to the nucleoside phosphoramidites currently used in oligonucleotide synthesis (see Phosphoramidite building blocks below). Many later improvements to the manufacturing of building blocks, oligonucleotide synthesizers, and synthetic protocols made the phosphoramidite chemistry a very reliable and expedient method of choice for the preparation of synthetic oligonucleotides.Synthesis by the phosphoramidite method

Building blocks

Nucleoside phosphoramidites

Protected 2'-deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites.

As mentioned above, the naturally occurring nucleotides (nucleoside-3'- or 5'-phosphates) and their phosphodiester analogs are insufficiently reactive to afford an expeditious synthetic preparation of oligonucleotides in high yields. The selectivity and the rate of the formation of internucleosidic linkages is dramatically improved by using 3'-O-(N,N-diisopropyl phosphoramidite) derivatives of nucleosides (nucleoside phosphoramidites) that serve as building blocks in phosphite triester methodology. To prevent undesired side reactions, all other functional groups present in nucleosides have to be rendered unreactive (protected) by attaching protecting groups. Upon the completion of the oligonucleotide chain assembly, all the protecting groups are removed to yield the desired oligonucleotides. Below, the protecting groups currently used in commercially available and most common nucleoside phosphoramidite building blocks are briefly reviewed:

- The 5'-hydroxyl group is protected by an acid-labile DMT (4,4'-dimethoxytrityl) group.

- Thymine and uracil, nucleic bases of thymidine and uridine, respectively, do not have exocyclic amino groups and hence do not require any protection.

- Although the nucleic base of guanosine and 2'-deoxyguanosine does have an exocyclic amino group, its basicity is low to an extent that it does not react with phosphoramidites under the conditions of the coupling reaction. However, a phosphoramidite derived from the N2-unprotected 5'-O-DMT-2'-deoxyguanosine is poorly soluble in acetonitrile, the solvent commonly used in oligonucleotide synthesis. In contrast, the N2-protected versions of the same compound dissolve in acetonitrile well and hence are widely used. Nucleic bases adenine and cytosine bear the exocyclic amino groups reactive with the activated phosphoramidites under the conditions of the coupling reaction. By the use of additional steps in the synthetic cycle or alternative coupling agents and solvent systems, the oligonucleotide chain assembly may be carried out using dA and dC phosphoramidites with unprotected amino groups. However, these approaches currently remain in the research stage. In routine oligonucleotide synthesis, exocyclic amino groups in nucleosides are kept permanently protected over the entire length of the oligonucleotide chain assembly.

- In the first, the standard and more robust scheme (Figure), Bz (benzoyl) protection is used for A, dA, C, and dC, while G and dG are protected with isobutyryl group. More recently, Ac (acetyl) group is used to protect C and dC as shown in Figure.

- In the second, mild protection scheme, A and dA are protected with isobutyryl or phenoxyacetyl groups (PAC). C and dC bear acetyl protection, and G and dG are protected with 4-isopropylphenoxyacetyl (iPr-PAC) or dimethylformamidino (dmf) groups. Mild protecting groups are removed more readily than the standard protecting groups. However, the phosphoramidites bearing these groups are less stable when stored in solution.

- The phosphite group is protected by a base-labile 2-cyanoethyl group. Once a phosphoramidite has been coupled to the solid support-bound oligonucleotide and the phosphite moieties have been converted to the P(V) species, the presence of the phosphate protection is not mandatory for the successful conducting of further coupling reactions.

2'-O-protected ribonucleoside phosphoramidites.

- In RNA synthesis, the 2'-hydroxy group is protected with TBDMS (t-butyldimethylsilyl) group. or with TOM (tri-iso-propylsilyloxymethyl) group, both being removable by treatment with fluoride ion.

- The phosphite moiety also bears a diisopropylamino (iPr2N) group reactive under acidic conditions. Upon activation, the diisopropylamino group leaves to be substituted by the 5'-hydroxy group of the support-bound oligonucleotide (see "Step 2: Coupling" below).

Non-nucleoside phosphoramidites

Non-nucleoside

phosphoramidites for 5'-modification of synthetic oligonucleotides. MMT

= mono-methoxytrityl,

(4-methoxyphenyl)diphenylmethyl.

Non-nucleoside phosphoramidites are the phosphoramidite reagents designed to introduce various functionalities at the termini of synthetic oligonucleotides or between nucleotide residues in the middle of the sequence. In order to be introduced inside the sequence, a non-nucleosidic modifier has to possess at least two hydroxy groups, one of which is often protected with the DMT group while the other bears the reactive phosphoramidite moiety.

Non-nucleosidic phosphoramidites are used to introduce desired groups that are not available in natural nucleosides or that can be introduced more readily using simpler chemical designs. A very short selection of commercial phosphoramidite reagents is shown in Scheme for the demonstration of the available structural and functional diversity. These reagents serve for the attachment of 5'-terminal phosphate (1), NH2 (2), SH (3), aldehydo (4), and carboxylic groups (5), CC triple bonds (6), non-radioactive labels and quenchers (exemplified by 6-FAM amidite 7 for the attachment of fluorescein and dabcyl amidite 8, respectively), hydrophilic and hydrophobic modifiers (exemplified by hexaethyleneglycol amidite 9 and cholesterol amidite 10, respectively), and biotin amidite 11.

Synthetic cycle

Scheme 5. Synthetic cycle for preparation of oligonucleotides by phosphoramidite method.

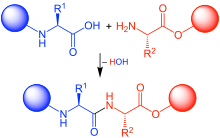

Oligonucleotide synthesis is carried out by a stepwise addition of nucleotide residues to the 5'-terminus of the growing chain until the desired sequence is assembled. Each addition is referred to as a synthetic cycle (Scheme 5) and consists of four chemical reactions:

Step 1: De-blocking (detritylation)

The DMT group is removed with a solution of an acid, such as 2% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or 3% dichloroacetic acid (DCA), in an inert solvent (dichloromethane or toluene). The orange-colored DMT cation formed is washed out; the step results in the solid support-bound oligonucleotide precursor bearing a free 5'-terminal hydroxyl group. It is worth remembering that conducting detritylation for an extended time or with stronger than recommended solutions of acids leads to depurination of solid support-bound oligonucleotide and thus reduces the yield of the desired full-length product.Step 2: Coupling

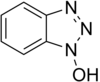

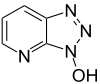

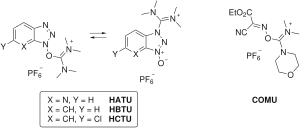

A 0.02–0.2 M solution of nucleoside phosphoramidite (or a mixture of several phosphoramidites) in acetonitrile is activated by a 0.2–0.7 M solution of an acidic azole catalyst, 1H-tetrazole, 5-ethylthio-1H-tetrazole, 2-benzylthiotetrazole, 4,5-dicyanoimidazole, or a number of similar compounds. A more extensive information on the use of various coupling agents in oligonucleotide synthesis can be found in a recent review. The mixing is usually very brief and occurs in fluid lines of oligonucleotide synthesizers (see below) while the components are being delivered to the reactors containing solid support. The activated phosphoramidite in 1.5 – 20-fold excess over the support-bound material is then brought in contact with the starting solid support (first coupling) or a support-bound oligonucleotide precursor (following couplings) whose 5'-hydroxy group reacts with the activated phosphoramidite moiety of the incoming nucleoside phosphoramidite to form a phosphite triester linkage. The coupling of 2'-deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites is very rapid and requires, on small scale, about 20 s for its completion. In contrast, sterically hindered 2'-O-protected ribonucleoside phosphoramidites require 5-15 min to be coupled in high yields. The reaction is also highly sensitive to the presence of water, particularly when dilute solutions of phosphoramidites are used, and is commonly carried out in anhydrous acetonitrile. Generally, the larger the scale of the synthesis, the lower the excess and the higher the concentration of the phosphoramidites is used. In contrast, the concentration of the activator is primarily determined by its solubility in acetonitrile and is irrespective of the scale of the synthesis. Upon the completion of the coupling, any unbound reagents and by-products are removed by washing.Step 3: Capping

The capping step is performed by treating the solid support-bound material with a mixture of acetic anhydride and 1-methylimidazole or, less often, DMAP as catalysts and, in the phosphoramidite method, serves two purposes.- After the completion of the coupling reaction, a small percentage of the solid support-bound 5'-OH groups (0.1 to 1%) remains unreacted and needs to be permanently blocked from further chain elongation to prevent the formation of oligonucleotides with an internal base deletion commonly referred to as (n-1) shortmers. The unreacted 5'-hydroxy groups are, to a large extent, acetylated by the capping mixture.

- It has also been reported that phosphoramidites activated with 1H-tetrazole react, to a small extent, with the O6 position of guanosine. Upon oxidation with I2 /water, this side product, possibly via O6-N7 migration, undergoes depurination. The apurinic sites thus formed are readily cleaved in the course of the final deprotection of the oligonucleotide under the basic conditions (see below) to give two shorter oligonucleotides thus reducing the yield of the full-length product. The O6 modifications are rapidly removed by treatment with the capping reagent as long as the capping step is performed prior to oxidation with I2/water.

- The synthesis of oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (OPS, see below) does not involve the oxidation with I2/water, and, respectively, does not suffer from the side reaction described above. On the other hand, if the capping step is performed prior to sulfurization, the solid support may contain the residual acetic anhydride and N-methylimidazole left after the capping step. The capping mixture interferes with the sulfur transfer reaction, which results in the extensive formation of the phosphate triester internucleosidic linkages in place of the desired PS triesters. Therefore, for the synthesis of OPS, it is advisable to conduct the sulfurization step prior to the capping step.

Step 4: Oxidation

The newly formed tricoordinated phosphite triester linkage is not natural and is of limited stability under the conditions of oligonucleotide synthesis. The treatment of the support-bound material with iodine and water in the presence of a weak base (pyridine, lutidine, or collidine) oxidizes the phosphite triester into a tetracoordinated phosphate triester, a protected precursor of the naturally occurring phosphate diester internucleosidic linkage. Oxidation may be carried out under anhydrous conditions using tert-Butyl hydroperoxide or, more efficiently, (1S)-(+)-(10-camphorsulfonyl)-oxaziridine (CSO). The step of oxidation may be substituted with a sulfurization step to obtain oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (see Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates and their synthesis below). In the latter case, the sulfurization step is best carried out prior to capping.Solid supports

In solid-phase synthesis, an oligonucleotide being assembled is covalently bound, via its 3'-terminal hydroxy group, to a solid support material and remains attached to it over the entire course of the chain assembly. The solid support is contained in columns whose dimensions depend on the scale of synthesis and may vary between 0.05 mL and several liters. The overwhelming majority of oligonucleotides are synthesized on small scale ranging from 10 nmol to 1 μmol. More recently, high-throughput oligonucleotide synthesis where the solid support is contained in the wells of multi-well plates (most often, 96 or 384 wells per plate) became a method of choice for parallel synthesis of oligonucleotides on small scale. At the end of the chain assembly, the oligonucleotide is released from the solid support and is eluted from the column or the well.Solid support material

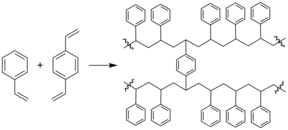

In contrast to organic solid-phase synthesis and peptide synthesis, the synthesis of oligonucleotides proceeds best on non-swellable or low-swellable solid supports. The two most often used solid-phase materials are controlled pore glass (CPG) and macroporous polystyrene (MPPS).- CPG is commonly defined by its pore size. In oligonucleotide chemistry, pore sizes of 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 3000 Å are used to allow the preparation of about 50, 80, 100, 150, and 200-mer oligonucleotides, respectively. To make native CPG suitable for further processing, the surface of the material is treated with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane to give aminopropyl CPG. The aminopropyl arm may be further extended to result in long chain aminoalkyl (LCAA) CPG. The amino group is then used as an anchoring point for linkers suitable for oligonucleotide synthesis (see below).

- MPPS suitable for oligonucleotide synthesis is a low-swellable, highly cross-linked polystyrene obtained by polymerization of divinylbenzene (min 60%), styrene, and 4-chloromethylstyrene in the presence of a porogeneous agent. The macroporous chloromethyl MPPS obtained is converted to aminomethyl MPPS.

Linker chemistry

Commercial solid supports for oligonucleotide synthesis.

Scheme 6. Mechanism of 3'-dephosphorylation of oligonucleotides assembled on universal solid supports.

To make the solid support material suitable for oligonucleotide synthesis, non-nucleosidic linkers or nucleoside succinates are covalently attached to the reactive amino groups in aminopropyl CPG, LCAA CPG, or aminomethyl MPPS. The remaining unreacted amino groups are capped with acetic anhydride. Typically, three conceptually different groups of solid supports are used.

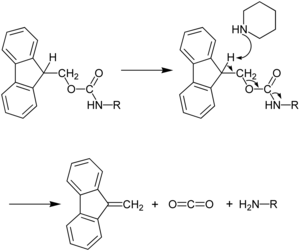

- Universal supports. In a more recent, more convenient, and more widely used method, the synthesis starts with the universal support where a non-nucleosidic linker is attached to the solid support material (compounds 1 and 2). A phosphoramidite respective to the 3'-terminal nucleoside residue is coupled to the universal solid support in the first synthetic cycle of oligonucleotide chain assembly using the standard protocols. The chain assembly is then continued until the completion, after which the solid support-bound oligonucleotide is deprotected. The characteristic feature of the universal solid supports is that the release of the oligonucleotides occurs by the hydrolytic cleavage of a P-O bond that attaches the 3’-O of the 3’-terminal nucleotide residue to the universal linker as shown in Scheme 6. The critical advantage of this approach is that the same solid support is used irrespectively of the sequence of the oligonucleotide to be synthesized. For the complete removal of the linker and the 3'-terminal phosphate from the assembled oligonucleotide, the solid support 1 and several similar solid supports require gaseous ammonia, aqueous ammonium hydroxide, aqueous methylamine, or their mixture and are commercially available. The solid support 2 requires a solution of ammonia in anhydrous methanol and is also commercially available.

- Nucleosidic solid supports. In a historically first and still popular approach, the 3'-hydroxy group of the 3'-terminal nucleoside residue is attached to the solid support via, most often, 3’-O-succinyl arm as in compound 3. The oligonucleotide chain assembly starts with the coupling of a phosphoramidite building block respective to the nucleotide residue second from the 3’-terminus. The 3’-terminal hydroxy group in oligonucleotides synthesized on nucleosidic solid supports is deprotected under the conditions somewhat milder than those applicable for universal solid supports. However, the fact that a nucleosidic solid support has to be selected in a sequence-specific manner reduces the throughput of the entire synthetic process and increases the likelihood of human error.

- Special solid supports are used for the attachment of desired functional or reporter groups at the 3’-terminus of synthetic oligonucleotides. For example, the commercial solid support 4 allows the preparation of oligonucleotides bearing 3’-terminal 3-aminopropyl linker. Similarly to non-nucleosidic phosphoramidites, many other special solid supports designed for the attachment of reactive functional groups, non-radioactive reporter groups, and terminal modifiers (e.c. cholesterol or other hydrophobic tethers) and suited for various applications are commercially available. A more detailed information on various solid supports for oligonucleotide synthesis can be found in a recent review.

Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates and their synthesis

Sp and Rp-diastereomeric internucleosidic phosphorothioate linkages.

Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (OPS) are modified oligonucleotides where one of the oxygen atoms in the phosphate moiety is replaced by sulfur. Only the phosphorothioates having sulfur at a non-bridging position as shown in figure are widely used and are available commercially. The replacement of the non-bridging oxygen with sulfur creates a new center of chirality at phosphorus. In a simple case of a dinucleotide, this results in the formation of a diastereomeric pair of Sp- and Rp-dinucleoside monophosphorothioates whose structures are shown in Figure. In an n-mer oligonucleotide where all (n – 1) internucleosidic linkages are phosphorothioate linkages, the number of diastereomers m is calculated as m = 2(n – 1). Being non-natural analogs of nucleic acids, OPS are substantially more stable towards hydrolysis by nucleases, the class of enzymes that destroy nucleic acids by breaking the bridging P-O bond of the phosphodiester moiety. This property determines the use of OPS as antisense oligonucleotides in in vitro and in vivo applications where the extensive exposure to nucleases is inevitable. Similarly, to improve the stability of siRNA, at least one phosphorothioate linkage is often introduced at the 3'-terminus of both sense and antisense strands. In chirally pure OPS, all-Sp diastereomers are more stable to enzymatic degradation than their all-Rp analogs. However, the preparation of chirally pure OPS remains a synthetic challenge. In laboratory practice, mixtures of diastereomers of OPS are commonly used.

Synthesis of OPS is very similar to that of natural oligonucleotides. The difference is that the oxidation step is replaced by sulfur transfer reaction (sulfurization) and that the capping step is performed after the sulfurization. Of many reported reagents capable of the efficient sulfur transfer, only three are commercially available:

Commercial sulfur transfer agents for oligonucleotide synthesis.

- 3-(Dimethylaminomethylidene)amino-3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-3-thione, DDTT (3) provides rapid kinetics of sulfurization and high stability in solution. The reagent is available from several sources.

- 3H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one 1,1-dioxide (4) also known as Beaucage reagent displays a better solubility in acetonitrile and short reaction times. However, the reagent is of limited stability in solution and is less efficient in sulfurizing RNA linkages.

- N,N,N'N'-Tetraethylthiuram disulfide (TETD) is soluble in acetonitrile and is commercially available. However, the sulfurization reaction of an internucleosidic DNA linkage with TETD requires 15 min, which is more than 10 times as slow as that with compounds 3 and 4.

Automation

In the past, oligonucleotide synthesis was carried out manually in solution or on solid phase. The solid phase synthesis was implemented using, as containers for the solid phase, miniature glass columns similar in their shape to low-pressure chromatography columns or syringes equipped with porous filters. Currently, solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis is carried out automatically using computer-controlled instruments (oligonucleotide synthesizers) and is technically implemented in column, multi-well plate, and array formats. The column format is best suited for research and large scale applications where a high-throughput is not required. Multi-well plate format is designed specifically for high-throughput synthesis on small scale to satisfy the growing demand of industry and academia for synthetic oligonucleotides. A number of oligonucleotide synthesizers for small scale synthesis and medium to large scale synthesis are available commercially.First commercially available oligonucleotide synthesizers

In March 1982 a practical course was hosted by the Department of Biochemistry, Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, Germany. M.H. Caruthers, M.J. Gait, H.G. Gassen, H.Koster, K. Itakura, and C. Birr among others attended. The program comprised practical work, lectures, and seminars on solid-phase chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides. A select group of 15 students attended and had an unprecedented opportunity to be instructed by the esteemed teaching staff.Along with manual exercises, several prominent automation companies attended the course. Biosearch of Novato, CA, Genetic Design of Watertown, MA, were two of several companies to demonstrate automated synthesizers at the course. Biosearch presented their new SAM I synthesizer. The Genetic Design had developed their synthesizer from the design of its sister companies (Sequemat) solid phase peptide sequencer. The Genetic Design arranged with Dr Christian Birr (Max-Planck-Institute for Medical Research) a week before the event to convert his solid phase sequencer into the semi-automated synthesizer. The team led by Dr Alex Bonner and Rick Neves converted the unit and transported it to Darmstadt for the event and installed into the Biochemistry lab at the Technische Hochschule. As the system was semi-automatic, the user injected the next base to be added to the growing sequence during each cycle. The system worked well and produced a series of test tubes filled with bright red trityl color indicating complete coupling at each step. This system was later fully automated by inclusion of an auto injector and was designated the Model 25A.

History of mid to large scale oligonucleotide synthesis

Large scale oligonucleotide synthesizers were often developed by augmenting the capabilities of a preexisting instrument platform. One of the first mid scale synthesizers appeared in the late 1980s, manufactured by the Biosearch company in Novato, CA (The 8800). This platform was originally designed as a peptide synthesizer and made use of a fluidized bed reactor essential for accommodating the swelling characteristics of polystyrene supports used in the Merrifield methodology. Oligonucleotide synthesis involved the use of CPG (controlled pore glass) which is a rigid support and is more suited for column reactors as described above. The scale of the 8800 was limited to the flow rate required to fluidize the support. Some novel reactor designs as well as higher than normal pressures enabled the 8800 to achieve scales that would prepare 1 mmole of oligonucleotide. In the mid 1990s several companies developed platforms that were based on semi-preparative and preparative liquid chromatographs. These systems were well suited for a column reactor approach. In most cases all that was required was to augment the number of fluids that could be delivered to the column. Oligo synthesis requires a minimum of 10 and liquid chromatographs usually accommodate 4. This was an easy design task and some semi-automatic strategies worked without any modifications to the preexisting LC equipment. PerSeptive Biosystems as well as Pharmacia (GE) were two of several companies that developed synthesizers out of liquid chromatographs. Genomic Technologies, Inc. was one of the few companies to develop a large scale oligonucleotide synthesizer that was, from the ground up, an oligonucleotide synthesizer. The initial platform called the VLSS for very large scale synthesizer utilized large Pharmacia liquid chromatograph columns as reactors and could synthesize up to 75 millimoles of material. Many oligonucleotide synthesis factories designed and manufactured their own custom platforms and little is known due to the designs being proprietary. The VLSS design continued to be refined and is continued in the QMaster synthesizer which is a scaled down platform providing milligram to gram amounts of synthetic oligonucleotide.The current practices of synthesis of chemically modified oligonucleotides on large scale have been recently reviewed.

Synthesis of oligonucleotide microarrays

One may visualize an oligonucleotide microarray as a miniature multi-well plate where physical dividers between the wells (plastic walls) are intentionally removed. With respect to the chemistry, synthesis of oligonucleotide microarrays is different from the conventional oligonucleotide synthesis in two respects:

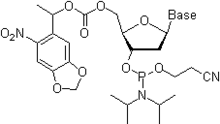

5'-O-MeNPOC-protected nucleoside phosphoramidite.

- Oligonucleotides remain permanently attached to the solid phase, which requires the use of linkers that are stable under the conditions of the final deprotection procedure.

- The absence of physical dividers between the sites occupied by individual oligonucleotides, a very limited space on the surface of the microarray (one oligonucleotide sequence occupies a square 25×25 μm) and the requirement of high fidelity of oligonucleotide synthesis dictate the use of site-selective 5'-deprotection techniques. In one approach, the removal of the 5'-O-DMT group is effected by electrochemical generation of the acid at the required site(s). Another approach uses 5'-O-(α-methyl-6-nitropiperonyloxycarbonyl) (MeNPOC) protecting group, which can be removed by irradiation with UV light of 365 nm wavelength.

Post-synthetic processing

After the completion of the chain assembly, the solid support-bound oligonucleotide is fully protected:- The 5'-terminal 5'-hydroxy group is protected with DMT group;

- The internucleosidic phosphate or phosphorothioate moieties are protected with 2-cyanoethyl groups;

- The exocyclic amino groups in all nucleic bases except for T and U are protected with acyl protecting groups.

Regardless of whether the phosphate protecting groups were removed first, the solid support-bound oligonucleotides are deprotected using one of the two general approaches.

- (1) Most often, 5'-DMT group is removed at the end of the oligonucleotide chain assembly. The oligonucleotides are then released from the solid phase and deprotected (base and phosphate) by treatment with aqueous ammonium hydroxide, aqueous methylamine, their mixtures, gaseous ammonia or methylamine or, less commonly, solutions of other primary amines or alkalies at ambient or elevated temperature. This removes all remaining protection groups from 2'-deoxyoligonucleotides, resulting in a reaction mixture containing the desired product. If the oligonucleotide contains any 2'-O-protected ribonucleotide residues, the deprotection protocol includes the second step where the 2'-O-protecting silyl groups are removed by treatment with fluoride ion by various methods. The fully deprotected product is used as is, or the desired oligonucleotide can be purified by a number of methods. Most commonly, the crude product is desalted using ethanol precipitation, size exclusion chromatography, or reverse-phase HPLC. To eliminate unwanted truncation products, the oligonucleotides can be purified via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or anion-exchange HPLC followed by desalting.

- (2) The second approach is only used when the intended method of purification is reverse-phase HPLC. In this case, the 5'-terminal DMT group that serves as a hydrophobic handle for purification is kept on at the end of the synthesis. The oligonucleotide is deprotected under basic conditions as described above and, upon evaporation, is purified by reverse-phase HPLC. The collected material is then detritylated under aqueous acidic conditions. On small scale (less than 0.01–0.02 mmol), the treatment with 80% aqueous acetic acid for 15–30 min at room temperature is often used followed by evaporation of the reaction mixture to dryness in vacuo. Finally, the product is desalted as described above.

- For some applications, additional reporter groups may be attached to an oligonucleotide using a variety of post-synthetic procedures.

Characterization

Deconvoluted ES MS of crude oligonucleotide 5'-DMT-T20

(calculated mass 6324.26 Da).

As with any other organic compound, it is prudent to characterize synthetic oligonucleotides upon their preparation. In more complex cases (research and large scale syntheses) oligonucleotides are characterized after their deprotection and after purification. Although the ultimate approach to the characterization is sequencing, a relatively inexpensive and routine procedure, the considerations of the cost reduction preclude its use in routine manufacturing of oligonucleotides. In day-by-day practice, it is sufficient to obtain the molecular mass of an oligonucleotide by recording its mass spectrum. Two methods are currently widely used for characterization of oligonucleotides: electrospray mass spectrometry (ES MS) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). To obtain informative spectra, it is very important to exchange all metal ions that might be present in the sample for ammonium or trialkylammonium [e.c. triethylammonium, (C2H5)3NH+] ions prior to submitting a sample to the analysis by either of the methods.

- In ES MS spectrum, a given oligonucleotide generates a set of ions that correspond to different ionization states of the compound. Thus, the oligonucleotide with molecular mass M generates ions with masses (M – nH)/n where M is the molecular mass of the oligonucleotide in the form of a free acid (all negative charges of internucleosidic phosphodiester groups are neutralized with H+), n is the ionization state, and H is the atomic mass of hydrogen (1 Da). Most useful for characterization are the ions with n ranging from 2 to 5. Software supplied with the more recently manufactured instruments is capable of performing a deconvolution procedure that is, it finds peaks of ions that belong to the same set and derives the molecular mass of the oligonucleotide.

- To obtain more detailed information on the impurity profile of oligonucleotides, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS or HPLC-MS) or capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry (CEMS) are used.