The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (Pub.L. 111–220) was an Act of Congress that was signed into federal law by United States President Barack Obama on August 3, 2010 that reduces the disparity between the amount of crack cocaine and powder cocaine needed to trigger certain federal criminal penalties from a 100:1 weight ratio to an 18:1 weight ratio and eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine, among other provisions. Similar bills were introduced in several U.S. Congresses before its passage in 2010, and courts had also acted to reduce the sentencing disparity prior to the bill's passage.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 implemented the initial disparity, reflecting Congress's view that crack cocaine was a more dangerous and harmful drug than powder cocaine. In the decades since, extensive research by the United States Sentencing Commission and other experts has suggested that the differences between the effects of the two drugs are exaggerated and that the sentencing disparity is unwarranted. Further controversy surrounding the 100:1 ratio was a result of its description by some as being racially biased and contributing to a disproportionate number of African Americans being sentenced for crack cocaine offenses. Legislation to reduce the disparity has been introduced since the mid-1990s, culminating in the signing of the Fair Sentencing Act.

The Act has been described as improving the fairness of the federal criminal justice system, and prominent politicians and non-profit organizations have called for further reforms, such as making the law retroactive and complete elimination of the disparity (i.e., enacting a 1:1 sentencing ratio).

Background

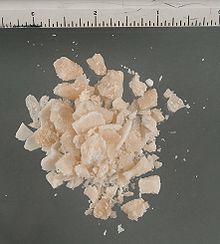

The use of crack cocaine increased rapidly in the 1980s, accompanied by an increase in violence in urban areas. In response, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 included a provision that created the disparity between federal penalties for crack cocaine and powder cocaine offenses, imposing the same penalties for the possession of an amount of crack cocaine as for 100 times the same amount of powder cocaine. The law also contained minimum sentences and other disparities between the two forms of the drug.

Sentencing disparity and effects

In the three decades prior to the passing of the Fair Sentencing Act, those who were arrested for possessing crack cocaine faced much more severe penalties than those in possession of powder cocaine. While a person found with five grams of crack cocaine faced a five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence, a person holding powder cocaine could receive the same sentence only if he or she held five hundred grams. Similarly, those carrying ten grams of crack cocaine faced a ten-year mandatory sentence, while possession of one thousand grams of powder cocaine was required for the same sentence to be imposed.

At that time, Congress provided the following five reasons for the high ratio: crack cocaine was more addictive than powder cocaine; crack cocaine was associated with violent crime; youth were more likely to be drawn to crack cocaine; crack cocaine was inexpensive, and therefore more likely to be consumed in large quantities; and use of crack cocaine by pregnant mothers was dangerous for their unborn children.

A study released in 1997 examined the addictive nature of both crack and powder cocaine and concluded that one was no more addictive than the other. The study explored other reasons why crack is viewed as more addictive and theorized, "a more accurate interpretation of existing evidence is that already abuse-prone cocaine users are most likely to move toward a more efficient mode of ingestion as they escalate their use. The Los Angeles Times commented, "There was never any scientific basis for the disparity, just panic as the crack epidemic swept the nation's cities."

The sentencing disparity between these two drug offenses is perceived by a number of commentators as racially biased. In 1995, the U.S. Sentencing Commission concluded that the disparity created a "racial imbalance in federal prisons and led to more severe sentences for low-level crack dealers than for wholesale suppliers of powder cocaine. ... As a result, thousands of people – mostly African Americans – have received disproportionately harsh prison sentences."

In 2002, the United States Sentencing Commission "found that the ratio was created based upon a misperception of the dangers of crack cocaine, which had since been proven to have a less drastic effect than previously thought." In 2009, the U.S. Sentencing Commission introduced figures stating that no class of drug is as racially skewed as crack in terms of numbers of offenses. According to the data, 79% of 5,669 sentenced crack offenders were black, while only 10% were white and 10% were Hispanic. The figures for the 6,020 powder cocaine convictions, in contrast, were as follows: 17% of these offenders were white, 28% were black, and 53% were Hispanic. Combined with a 115-month average imprisonment for crack offenses, compared with an average of 87 months for cocaine offenses, the sentencing disparity results in more African-Americans spending more time in the prison system.

Asa Hutchinson, the former administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration under President George W. Bush, commented that because of the disparate treatment of these two offenses, "the credibility of our entire drug enforcement system is weakened." The U.S. Sentencing Commission also released a statement saying that "perceived improper racial disparity fosters disrespect for and lack of confidence in the criminal justice system." According to U.S. Senator Dick Durbin, "The sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine has contributed to the imprisonment of African Americans at six times the rate of Whites and to the United States' position as the world's leader in incarcerations."

Attempts to change the disparity

Legal challenges

Although the 100:1 federal sentencing ratio remained unchanged from 1986 to 2010, two U.S. Supreme Court cases provided lower courts with discretion in determining penalties for cocaine convictions. Kimbrough v. United States (2007) and Spears v. United States gave lower courts the option to set penalties and allowed judges who disagreed with the Federal Sentencing Guidelines to depart from the statutory ratio based on policy concerns. In 2009, the U.S. District Courts for the Western District of Pennsylvania, Western District of Virginia and District of Columbia used these cases to create one-to-one sentencing ratios of crack cocaine to powder cocaine. United States v. Booker (2005) and Blakely v. Washington (2004) also weakened the sentencing guidelines as a whole by making them advisory.

Proposed legislation

The U.S. Sentencing Commission first called for reform of the 100:1 sentencing disparity in 1994 after a year-long study on the differing penalties for powder and crack cocaine required by the Omnibus Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The Commission found that the sentencing disparity was unjustified due to the small differences between the two forms of cocaine, and advised Congress to equalize the quantity ratio that would trigger mandatory sentences. Congress rejected the Commission's recommendations for the first time in the Commission's history.

In April 1997, the Commission again recommended a reduction in the disparity, providing Congress with a range from 2:1 to 15:1 to choose from. This recommendation would have raised the quantity of crack and lowered the quantity of powder cocaine required to trigger a mandatory minimum sentence. Congress did not act on this recommendation. In 2002, the Commission again called for reducing sentencing disparities in its Report to Congress based on extensive research and testimony by medical and scientific professionals, federal and local law enforcement officials, criminal justice practitioners, academics, and civil rights organizations.

Congress first proposed bipartisan legislation to reform crack cocaine sentencing in 2001, when Senator Jeff Sessions (R-AL) introduced the Drug Sentencing Reform Act. This proposal would have raised the amount of crack cocaine necessary for a five-year mandatory minimum from 5 grams to 20 grams and would have lowered the amount of powder cocaine necessary for the same sentence from 500 grams to 400 grams, a 20:1 ratio. During the 110th United States Congress, seven crack cocaine sentencing reform bills were introduced that would have reduced the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses without increasing mandatory sentences.

In the Senate, Orrin Hatch (R-UT) sponsored the Fairness in Drug Sentencing Act of 2007 (S. 1685) that would have created a 20:1 ratio by increasing the five-year quantity trigger for mandatory minimum sentences for crack cocaine to 25 grams and leaving the powder cocaine level at 500 grams. Former senator and former Vice President of the United States Joe Biden sponsored the Drug Sentencing Reform and Cocaine Kingpin Trafficking Act of 2007 (S. 1711), which would have completely eliminated the disparity by increasing the amount of crack cocaine required for the imposition of mandatory minimum prison terms to those of powder cocaine.

Both of these bills would have eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum prison term for first-time possession of crack cocaine. In the House of Representatives, Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) sponsored the Drug Sentencing Reform and Cocaine Kingpin Trafficking Act of 2007 (H.R. 4545), the companion to Biden's proposed bill. Charles Rangel sponsored the Crack-Cocaine Equitable Sentencing Act of 2007 (H.R. 460), a bill he had been introducing since the mid-1990s that would have equalized cocaine sentencing and eliminated specified mandatory minimum penalties relating to the trafficking in, and possession, importation, or distribution of, crack cocaine.

The FIRST STEP Act, passed in December 2018, retroactively applied the Fair Sentencing Act, aiding around 2,600 imprisoned people.

Opposition to the Act

Some members of Congress opposed the Act. Lamar S. Smith (R-TX), the top-ranking Republican on the United States House Committee on the Judiciary, argued against its passage stating, "I cannot support legislation that might enable the violent and devastating crack cocaine epidemic of the past to become a clear and present danger." Specifically, Smith alleged that because "reducing the penalties for crack cocaine could expose our neighborhoods to the same violence and addiction that caused Congress to act in the first place," the bill risked a return to the crack cocaine epidemic that "ravaged our communities, especially minority communities." Smith claimed that the severe sentences for crack cocaine were justified by a high correlation between crack cocaine arrests and both violent crime and past criminal history.

The Fraternal Order of Police, a national organization of law enforcement officers, also opposed the Act. It argued that because increased violence is associated with the use of crack, especially in urban areas, high penalties for crack-related offenses were justified, relying on U.S. Sentencing Commission statistics showing that 29% of all crack cases from October 1, 2008, through September 30, 2009, involved a weapon, compared to only 16% for powder cocaine. The organization also stated that the enhanced penalties for crack cocaine "have proven useful, and a better course of action would have been to instead raise the penalties for powder cocaine crimes." The Fair Sentencing Act includes a provision to account for such aggravated cases, allowing penalties to be increased for the use of violence during a drug trafficking offense.

The National Sheriffs' Association (NSA) opposed the bill, stating that "Both crack and powder cocaine are dangerous narcotics and plights [sic] on communities throughout the United States. ... NSA would consider supporting legislation that would increase the sentence for powder cocaine, rather than significantly reducing the sentence for crack cocaine."

Proposal and passage of the bill

On July 29, 2009, the United States House Committee on the Judiciary passed proposed legislation, the Fairness in Cocaine Sentencing Act (H.R.3245), a bill sponsored by Bobby Scott. Co-sponsored by a group of 62 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, including Dennis Kucinich and Ron Paul, the bill would have completely eliminated the sentencing disparity. The Fair Sentencing Act was introduced as compromise legislation to get bipartisan and unanimous support, amended to merely reduce the 100:1 disparity to 18:1.

The Fair Sentencing Act (S. 1789) was authored by Assistant Senate Majority Leader Dick Durbin (D-IL) and cosponsored by Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and ranking member Jeff Sessions (R-AL). The bill passed the U.S. Senate on March 17, 2010 and passed the U.S. House of Representatives on July 27, 2010, with House Majority Whip James E. Clyburn (D-SC) and Bobby Scott (D-VA) as key supporters. The bill was then sent to President Obama and signed into law on August 3, 2010.

Key provisions

The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 amended the Controlled Substances Act and the Controlled Substances Import and Export Act by increasing the amount of a controlled substance or mixture containing a cocaine base (i.e., crack cocaine) that would result in mandatory minimum prison terms for trafficking and by increasing monetary penalties for drug trafficking and for importing/exporting controlled substances. The five-year mandatory minimum for first-time possession of crack cocaine was also eliminated, and sentencing may take account of accompanying violence, among other aggravating factors.

The bill directed the United States Sentencing Commission to take four actions:

- review and amend its sentencing guidelines to increase sentences for those convicted of committing violent acts in the course a drug trafficking offense;

- incorporate aggravating and mitigating factors in its guidelines for drug trafficking offenses;

- announce all guidelines, policy statements, and amendments required by the act no later than 90 days after its enactment; and

- study and report to Congress on the impact of changes in sentencing law under this act.

In addition, the bill requires the Comptroller General to report to Congress with an analysis of the effectiveness of drug court programs under the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. This must be done within one year after the enactment of the Fair Sentencing Act.

Impact and reception

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that implementing the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 will reduce the prison population by 1,550 person-years over the time period from 2011–2015, creating a monetary savings of $42 million during that period. The CBO also estimates that the Act's requirement for the Government Accountability Office to conduct a report on the effectiveness of a Department of Justice grant program to treat nonviolent drug offenders would cost less than $500,000 from appropriated funds.

On October 15, 2010, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted 6-1 to approve a temporary amendment to federal sentencing guidelines to reflect the changes made by the Fair Sentencing Act. The Commission changed the sentencing guidelines to reflect Congress's increasing the amount of crack cocaine that would trigger a five-year mandatory minimum sentence from 5 grams to 28 grams (one ounce) and the amount that would trigger a ten-year mandatory minimum from 50 grams to 280 grams. The amendment also lists aggravating factors to the guidelines, creating harsher sentences for crack cocaine offenses involving violence or bribery of law enforcement officials. The Commission made the amendment permanent on June 30, 2011.

Effective November 1, 2011, the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 applies retroactively to reduce the sentences of certain offenders already sentenced for federal crack cocaine offenses before the passage of the bill. However, the nonprofit organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums, a major advocate of the Fair Sentencing Act, has lobbied Congress to make the entire act retroactive. According to Gil Kerlikowske, Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, "there is no scientific basis for the disparity and by promoting laws and policies that treat all Americans equally, and by working to amend or end those that do not, we can only increase public confidence in the criminal justice system and help create a safer and healthier nation for us all."

Progressives argue for elimination of the sentencing disparity altogether and believe that the impact of the bill on racial disparities in drug enforcement may be limited for several reasons. First, while the bill reduces the ratio between crack and powder cocaine sentencing, it does not achieve full parity. Second, the Act does not address the enforcement prerogatives of federal criminal justice agencies: while African-American defendants account for roughly 80% of those arrested for crack-related offenses, public health data has found that two-thirds of crack users are white or Hispanic. Third, the Act does not reduce sentences for those prosecuted under state law, and state prosecutions account for a vast majority of incarcerations for drug-related offenses.