Solar Power Plant Telangana II in state of Telangana, India

India is one of the countries with the largest production of energy from renewable sources.

In the electricity sector, renewable energy account for 34.6% of the total installed power capacity.

Large hydro installed capacity was 45.399 GW as of 31 March 2019, contributing to 13% of the total power capacity.

The remaining renewable energy sources accounted for 22% of the total installed power capacity (77.641 GW) as of 31 March 2019.

Wind power capacity was 36,625 MW as of 31 March 2019, making

India the fourth-largest wind power producer in the world.

The country has a strong manufacturing base in wind power with 20

manufactures of 53 different wind turbine models of international

quality up to 3 MW in size with exports to Europe, the United States and

other countries.

Wind or Solar PV paired with four-hour battery storage systems is

already cost competitive, without subsidy, as a source of dispatchable

generation compared with new coal and new gas plants in India.

The government target of installing 20 GW of solar power by 2022

was achieved four years ahead of schedule in January 2018, through both

solar parks as well as roof-top solar panels.

India has set a new target of achieving 100 GW of solar power by 2022.

Four of the top seven largest solar parks worldwide are in India including the second largest solar park in the world at Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh, with a capacity of 1000 MW. The world's largest solar power plant, Bhadla Solar Park is being constructed in Rajasthan with a capacity of 2255 MW and is expected to be completed by the end of 2018.

Biomass power from biomass combustion, biomass gasification and bagasse cogeneration reached 9.1 GW installed capacity as of 31 March 2019. Family type biogas plants reached 3.98 million.

Renewable energy in India comes under the purview of the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE).

India was the first country in the world to set up a ministry of non-conventional energy resources, in the early 1980s. Solar Energy Corporation of India is responsible for the development of solar energy industry in India. Hydroelectricity is administered separately by the Ministry of Power and not included in MNRE targets.

India is running one of the largest and most ambitious renewable

capacity expansion programs in the world.

Newer renewable electricity sources are projected to grow massively by

nearer term 2022 targets, including a more than doubling of India's

large wind power capacity and an almost 15 fold increase in solar power

from April 2016 levels.

These targets would place India among the world leaders in renewable

energy use and place India at the centre of its "Sunshine Countries" International Solar Alliance project promoting the growth and development of solar power internationally to over 120 countries.

India set a target of achieving 40% of its total electricity generation from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030, as stated in its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions statement in the Paris Agreement.

A blueprint draft published by Central Electricity Authority projects that 57% of the total electricity capacity will be from renewable sources by 2027.

In the 2027 forecasts, India aims to have a renewable energy installed

capacity of 275 GW, in addition to 72 GW of hydro-energy, 15 GW of

nuclear energy and nearly 100 GW from “other zero emission” sources.

Renewable energy overview and targets

Installed grid interactive renewable power capacity in India as of 31 May 2018 (excluding large hydro)

- Wind Power: 34,046 MW (49.3%)

- Solar Power: 21,651 MW (31.4%)

- Biomass Power: 8,701 MW (12.6%)

- Small Hydro Power: 4,486 MW (6.5%)

- Waste-to-Power: 138 MW (0.2%)

The 2022 electrical power targets include achieving 227GW (earlier

175 GW) of energy from renewable sources - nearly 113 GW through solar power, 66 GW from wind power, 10 GW from biomass power, 5GW from small hydro and 31GW from floating solar and offshore wind power.

The bidding process for the further additional 115 GW or thereabouts to

meet these targets of installed capacity from January 2018 levels will

be completed by the end of 2019-2020.

The government has announced that no new coal-based capacity addition

is required beyond the 50 GW under different stages of construction

likely to come online between 2017 and 2022.

Unlike most countries, until 2019 India did not count large hydro

power towards renewable energy targets as hydropwer was under the older

Ministry of Power instead of Ministry of New and Renewable Energy.

This system was changed in 2019 and the power from large hydropower

plants is since also accounted for.

This was done to help the sale of the power from the large Hydropower

plants, as this reclassification has made such plants able to sell their

power under the Renewable Energy Purchase Obligation.

Under the Renewable Energy Purchase Obligation, the DISCOMs

(Distribution Company) of the various states have to source a certain

percentage of their power from Renewable Energy Sources under two

categories Solar and Non-Solar. The power from the large Hydropower

plants now classifies under the Non-Solar Renewable Energy Category.

Grid connected renewable electricity

| Source | Total Installed Capacity (MW) | 2022 target (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| Wind power | 36,625 | 60,000 |

| Solar power | 28,181 | 100,000 |

| Biomass power (Biomass & Gasification and Bagasse Cogeneration) |

9,103 | *10,000 |

| Waste-to-Power | 138 | |

| Small hydropower | 4,593 | 5,000 |

| TOTAL | 77,641 | 175,000 |

* The target is given for "bio-power" which includes biomass power and waste to power generation.

- Coal: 196,957.5 MW (57.3%)

- Renewable, except large Hydroelectric: 69,022.39 MW (20.1%)

- Large Hydro: 45,403.42 MW (13.2%)

- Gas: 24,897.46 MW (7.2%)

- Nuclear: 6,780 MW (2.0%)

- Diesel: 837.63 MW (0.2%)

The figures above refer to newer and fast developing renewable energy

sources and are managed by the Ministry for New and Renewable Energy

(MNRE). In addition as of 31 March 2018 India had 45.4 GW of installed

large hydro capacity which comes under the ambit of Ministry of Power.

In terms of meeting its ambitious 2022 targets, as of 31 March

2017, wind power was more than halfway towards its goal, whilst solar

power was below 13% of its highly ambitious target, although expansion

is expected to be dramatic in the near future. Bio energy was at just

above 80% mark whilst small hydro power was already 85% of the way to

meet its target. Overall India was at 33% towards meeting its 2022

renewable installed power capacity target of 175 GW. The total breakdown

of installed grid connected capacity from all sources including large

hydro was as follows:

| Source | Installed Capacity (MW) | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Coal | 196,957.50 | 57.27% |

| Large hydro | 45,403.42 | 13.20% |

| Other renewables | 69,022.39 | 20.07% |

| Gas | 24,897.46 | 7.23% |

| Diesel | 837.63 | 0.24% |

| Nuclear | 6,780.00 | 1.97% |

| Total | 343,898.39 | 100.00% |

The fast growing renewable energy sources under the responsibility of

the Ministry for New and Renewable Energy exceeded the installed

capacity of large hydro installations. This figure is targeted to reach

175 GW by 2022. Coal power currently represents the largest share of

installed capacity at just under 197 GW. Total installed capacity as of

31 May 2016, for grid connected power in India stood at a little under

344 GW.

Off-grid renewable energy

| Source | Total Installed Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|

| Biomass (non-bagasse) Cogeneration | 661.40 |

| SPV Systems | 539.13 |

| Biomass Gasifiers | 163.37 |

| Waste to Energy | 175.45 |

| Aero-Generators / Hybrid systems | 3.29 |

| TOTAL | 1,542.65 |

| Other Renewable Energy Systems | |

| Family Biogas Plants (in Lakhs) | 49.56 |

| Water mills / micro hydel (Nos.) | 2690/72 |

Renewable electricity generation

Total renewable energy which includes large hydro with pumped storage

generation, is nearly 17.5% of total utility electricity generation in

India during the year 2017-18.

Solar, wind and run of the river hydro being must run power generation

and environment friendly, base load coal fired power is transforming in

to load following power generation. In addition, renewable peaking hydro power capacity also caters peak load demand on daily basis.

| Source | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Hydro | 129,244 | 121,377 | 122,313 | 126,134 | 135,040 |

| Small Hydro | 8,060 | 8,355 | 7,673 | 5,056 | 8,703 |

| Solar | 4,600 | 7,450 | 12,086 | 25,871 | 39,268 |

| Wind | 28,214 | 28,604 | 46,011 | 52,666 | 62,036 |

| Bio mass | 14,944 | 16,681 | 14,159 | 15,252 | 16,325 |

| Other | 414 | 269 | 213 | 358 | 425 |

| Total | 191,025 | 187,158 | 204,182 | 227,973 | 261,797 |

| Total utility power | 1,105,446 | 1,168,359 | 1,236,392 | 1,302,904 | 1,371,517 |

| % Renewable power | 17.28% | 16.02% | 16.52% | 17.50% | 19.1% |

Hydroelectric power

India is the 7th largest producer of hydroelectric power in the world. As of 30 April 2017, India's installed utility-scale hydroelectric capacity was 44,594 MW, or 13.5% of its total utility power generation capacity.

Additional smaller hydroelectric power units with a total

capacity of 4,380 MW (1.3% of its total utility power generation

capacity) have been installed.

Small hydropower, defined to be generated at facilities with nameplate

capacities up to 25 MW, comes under the ambit of the Ministry of New and

Renewable energy (MNRE); whilst large hydro, defined as above 25 MW,

comes under the ambit of Ministry of Power.

Wind power

The largest wind farm of India in Muppandal, Tamil Nadu.

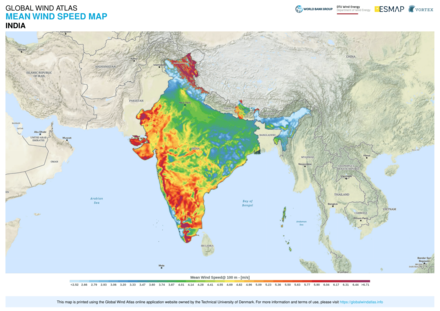

Mean wind speed in India.

The development of wind power in India began in the 1990s, and

has significantly increased in the last few years. Although a relative

newcomer to the wind industry compared with Denmark or the US, domestic policy support for wind power has led India to become the country with the fourth largest installed wind power capacity in the world.

As of 30 June 2018 the installed capacity of wind power in India was 34,293 MW, mainly spread across Tamil Nadu (7,269.50 MW), Maharashtra (4,100.40 MW), Gujarat (3,454.30 MW), Rajasthan (2,784.90 MW), Karnataka (2,318.20 MW), Andhra Pradesh (746.20 MW) and Madhya Pradesh (423.40 MW) Wind power accounts for 10% of India's total installed power capacity. India has set an ambitious target to generate 60,000 MW of electricity from wind power by 2022.

The Indian Government's Ministry of New and Renewable Energy announced a new wind-solar hybrid policy in May 2018. This means that the same piece of land will be used to house both wind farms and solar panels.

Solar power

Global Horizontal Irradiance in India.

India is densely populated and has high solar insolation, an ideal combination for using solar power in India.

Announced in November 2009, the Government of India proposed to launch its Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission under the National Action Plan on Climate Change. The program was inaugurated by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on 11 January 2010

with a target of 20GW grid capacity by 2022 as well as 2GW off-grid

installations, this target was later increased to 100 GW by the same

date under the Narendra Modi government in the 2015 Union budget of India.

Achieving this National Solar Mission target would establish India in

its ambition to be a global leader in solar power generation.

The Mission aims to achieve grid parity (electricity delivered at the

same cost and quality as that delivered on the grid) by 2022.

The National Solar Mission is also promoted and known by its more

colloquial name of "Solar India".The earlier objectives of the mission

were to install 1,000 MW of power by 2013 and cover 20×106 m2 (220×106 sq ft) with collectors by the end of the final phase of the mission in 2022.

On 30 November 2015 the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and the Prime Minister of France Francois Hollande launched the International Solar Alliance.The

ISA is an alliance of 121 solar rich countries lying partially or fully

between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, a number of

countries outside of this area are also involved with the organisation.

The ISA aims to promote and develop solar power amongst its members and

has the objective of mobilising $1 trillion of investment by 2030.

Much of the country does not have an electrical grid,

so one of the first applications of solar power was for water pumping,

to begin replacing India's four to five million diesel powered water pumps, each consuming about 3.5 kilowatts, and off-grid lighting. Some large projects have been proposed, and a 35,000 km2 (14,000 sq mi) area of the Thar Desert has been set aside for solar power projects, sufficient to generate 700 to 2,100 gigawatts. Solar power in India has been growing at a rate of 113% yoy and now dropped to around ₹4.34 (6.3¢ US) per kWh, which is around 18% lower than the average price for electricity generated by coal-fired plants.

As part of India's ambitious solar programme the central government has set up a US$350 million fund and the Yes Bank will loan US$5 billion to finance solar projects (c. January 2018). India is also the home to the world's first and only 100% solar powered airport, located at Cochin, Kerala.

India also has a wholly 100% solar powered railway station in Guwhati,

Assam. India's first and the largest floating solar power plant was

constructed at Banasura Sagar reservoir in Wayanad, Kerala.

The Indian Solar Loan Programme, supported by the United Nations Environment Programme has won the prestigious Energy Globe

World award for Sustainability for helping to establish a consumer

financing program for solar home power systems. Over the span of three

years more than 16,000 solar home systems have been financed through

2,000 bank branches, particularly in rural areas of South India where

the electricity grid does not yet extend.

Launched in 2003, the Indian Solar Loan Programme was a four-year

partnership between UNEP, the UNEP Risoe Centre, and two of India's

largest banks, the Canara Bank and Syndicate Bank.

Biomass

India is an ideal environment for Biomass production given its

tropical location and abundant sunshine and rains. The countries vast

agricultural potential provides huge agro-residues which can be used to

meet energy needs, both in heat and power applications..According to

IREDA "Biomass is capable of supplementing the coal to the tune of about

260 million tonnes", "saving of about Rs. 250 billion, every year."

It is estimated that the potential for biomass energy in India includes

16,000 MW from biomass energy and a further 3,500 MW from bagasse

cogeneration.

Biomass materials that can be used for power generation include

bagasse, rice husk, straw, cotton stalk, coconut shells, soya husk,

de-oiled cakes, coffee waste, jute wastes, groundnut shells and saw

dust.

| Type of Agro residues | Quantity(Million Tonnes / annum) |

|---|---|

| Straws of various pulses & cereals | 225.50 |

| Bagasse | 31.00 |

| Rice Husk | 10.00 |

| Groundnut shell | 11.10 |

| Stalks | 2.00 |

| Various Oil Stalks | 4.50 |

| Others | 65.90 |

| Total | 350.00 |

Biogas

In 2018,

India has set target to produce 15 million tons (62 mmcmd) of

biogas/bio-CNG by installing 5,000 large scale commercial type biogas

plants which can produce daily 12.5 tons of bio-CNG by each plant. The rejected organic solids from biogas plants can be used after Torrefaction in the existing coal fired plants to reduce coal consumption.

Bio protein

Synthetic methane (SNG) generated using electricity from carbon neutral renewable power or Bio CNG can be used to produce protein rich feed for cattle, poultry and fish economically by cultivating Methylococcus capsulatus bacteria culture with tiny land and water foot print.

The carbon dioxide gas produced as by product from these bio protein

plants can be recycled in the generation of SNG. Similarly, oxygen gas

produced as by product from the electrolysis of water and the methanation

process can be consumed in the cultivation of bacteria culture. With

these integrated plants, the abundant renewable power potential in India

can be converted in to high value food products with out any water

pollution or green house gas

(GHG) emissions for achieving food security at a faster pace with

lesser people deployment in agriculture / animal husbandry sector.

Biofuel

Ethanol

Ethanol market penetration reached its highest figure of a 3.3% blend rate in India in 2016.

It is produced from sugarcane molasses and partly from grains and can

be blended with gasoline. Sugarcane or sugarcane juice may not be used

for the production of ethanol in India.

Biodiesel

The

market for biodiesel remains at an early stage in India with the

country achieving a minimal blend rate with diesel of 0.001% in 2016.

Initially development was focussed on the jatropha (jatropha curcas)

plant as the most suitable inedible oilseed for biodiesel production.

Development of biodiesel from jatropha

has met a number of agronomic and economic restraints and attention is

now moving towards other feedstock technologies which utilize used

cooking oils, other unusable oil fractions, animal fat and inedible

oils.

Waste to energy

Every

year, about 55 million tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) and 38

billion litres of sewage are generated in the urban areas of India. In

addition, large quantities of solid and liquid wastes are generated by

industries. Waste generation in India is expected to increase rapidly in

the future.

As more people migrate to urban areas and as incomes increase,

consumption levels are likely to rise, as are rates of waste generation.

It is estimated that the amount of waste generated in India will

increase at a per capita rate of approximately 1-1.33% annually.

This has significant impacts on the amount of land that is and will be

needed for disposal, economic costs of collecting and transporting

waste, and the environmental consequences of increased MSW generation

levels.

India has had a long involvement with anaerobic digestion and biogas technologies.

Waste water treatment plants in the country have been established which produce renewable energy from sewage gas.

However, there is still significant untapped potential.

Also wastes from the distillery sector are on some sites converted into biogas to run in a gas engine to generate onsite power. Prominent companies in the waste to energy sector include:

- A2Z Group of companies

- Hanjer Biotech Energies

- Ramky Enviro Engineers Ltd

- Arka BRENStech Pvt Ltd

- Hitachi Zosen India Pvt Limited

- Clarke Energy

- ORS Group