Wave Power Station using a pneumatic Chamber

Wave power is the capture of energy of wind waves to do useful work – for example, electricity generation, water desalination, or pumping water. A machine that exploits wave power is a wave energy converter (WEC).

Wave power is distinct from tidal power,

which captures the energy of the current caused by the gravitational

pull of the Sun and Moon. Waves and tides are also distinct from ocean currents which are caused by other forces including breaking waves, wind, the Coriolis effect, cabbeling, and differences in temperature and salinity.

Wave-power generation is not a widely employed commercial

technology, although there have been attempts to use it since at least

1890.

In 2000 the world's first commercial Wave Power Device, the Islay LIMPET was installed on the coast of Islay in Scotland and connected to the National Grid. In 2008, the first experimental multi-generator wave farm was opened in Portugal at the Aguçadoura Wave Park.

Physical concepts

When an object bobs up and down on a ripple in a pond, it follows approximately an elliptical trajectory.

Motion of a particle in an ocean wave. A = At deep water. The elliptical motion of fluid particles decreases rapidly with increasing depth below the surface. B = At shallow water (ocean floor is now at B). The elliptical movement of a fluid particle flattens with decreasing depth. 1 = Propagation direction. 2 = Wave crest. 3 = Wave trough.

Photograph of the elliptical trajectories of water particles under a – progressive and periodic – surface gravity wave in a wave flume. The wave conditions are: mean water depth d = 2.50 ft (0.76 m), wave height H = 0.339 ft (0.103 m), wavelength λ = 6.42 ft (1.96 m), period T = 1.12 s.

Waves are generated by wind passing over the surface of the sea. As

long as the waves propagate slower than the wind speed just above the

waves, there is an energy transfer from the wind to the waves. Both air

pressure differences between the upwind and the lee side of a wave crest, as well as friction on the water surface by the wind, making the water to go into the shear stress causes the growth of the waves.

Wave height

is determined by wind speed, the duration of time the wind has been

blowing, fetch (the distance over which the wind excites the waves) and

by the depth and topography of the seafloor (which can focus or disperse

the energy of the waves). A given wind speed has a matching practical

limit over which time or distance will not produce larger waves. When

this limit has been reached the sea is said to be "fully developed".

In general, larger waves are more powerful but wave power is also determined by wave speed, wavelength, and water density.

Oscillatory motion is highest at the surface and diminishes exponentially with depth. However, for standing waves (clapotis) near a reflecting coast, wave energy is also present as pressure oscillations at great depth, producing microseisms. These pressure fluctuations at greater depth are too small to be interesting from the point of view of wave power.

The waves propagate on the ocean surface, and the wave energy is also transported horizontally with the group velocity. The mean transport rate of the wave energy through a vertical plane of unit width, parallel to a wave crest, is called the wave energy flux (or wave power, which must not be confused with the actual power generated by a wave power device).

Wave power formula

In deep water where the water depth is larger than half the wavelength, the wave energy flux is

with P the wave energy flux per unit of wave-crest length, Hm0 the significant wave height, Te the wave energy period, ρ the water density and g the acceleration by gravity. The above formula states that wave power is proportional to the wave energy period and to the square

of the wave height. When the significant wave height is given in

metres, and the wave period in seconds, the result is the wave power in

kilowatts (kW) per metre of wavefront length.

Example: Consider moderate ocean swells, in deep water, a few km

off a coastline, with a wave height of 3 m and a wave energy period of 8

seconds. Using the formula to solve for power, we get

meaning there are 36 kilowatts of power potential per meter of wave crest.

In major storms, the largest waves offshore are about 15 meters

high and have a period of about 15 seconds. According to the above

formula, such waves carry about 1.7 MW of power across each metre of

wavefront.

An effective wave power device captures as much as possible of

the wave energy flux. As a result, the waves will be of lower height in

the region behind the wave power device.

Wave energy and wave-energy flux

In a sea state, the average(mean) energy density per unit area of gravity waves on the water surface is proportional to the wave height squared, according to linear wave theory:

where E is the mean wave energy density per unit horizontal area (J/m2), the sum of kinetic and potential energy density per unit horizontal area. The potential energy density is equal to the kinetic energy, both contributing half to the wave energy density E, as can be expected from the equipartition theorem. In ocean waves, surface tension effects are negligible for wavelengths above a few decimetres.

As the waves propagate, their energy is transported. The energy transport velocity is the group velocity. As a result, the wave energy flux, through a vertical plane of unit width perpendicular to the wave propagation direction, is equal to:

with cg the group velocity (m/s).

Due to the dispersion relation for water waves under the action of gravity, the group velocity depends on the wavelength λ, or equivalently, on the wave period T. Further, the dispersion relation is a function of the water depth h. As a result, the group velocity behaves differently in the limits of deep and shallow water, and at intermediate depths:

Deep-water characteristics and opportunities

Deep

water corresponds with a water depth larger than half the wavelength,

which is the common situation in the sea and ocean. In deep water,

longer-period waves propagate faster and transport their energy faster.

The deep-water group velocity is half the phase velocity. In shallow water,

for wavelengths larger than about twenty times the water depth, as

found quite often near the coast, the group velocity is equal to the

phase velocity.

History

The first known patent to use energy from ocean waves dates back to 1799, and was filed in Paris by Girard and his son. An early application of wave power was a device constructed around 1910 by Bochaux-Praceique to light and power his house at Royan, near Bordeaux in France. It appears that this was the first oscillating water-column type of wave-energy device. From 1855 to 1973 there were already 340 patents filed in the UK alone.

Modern scientific pursuit of wave energy was pioneered by Yoshio Masuda's experiments in the 1940s.

He tested various concepts of wave-energy devices at sea, with several

hundred units used to power navigation lights. Among these was the

concept of extracting power from the angular motion at the joints of an

articulated raft, which was proposed in the 1950s by Masuda.

A renewed interest in wave energy was motivated by the oil crisis in 1973. A number of university researchers re-examined the potential to generate energy from ocean waves, among whom notably were Stephen Salter from the University of Edinburgh, Kjell Budal and Johannes Falnes from Norwegian Institute of Technology (now merged into Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Michael E. McCormick from U.S. Naval Academy, David Evans from Bristol University, Michael French from University of Lancaster, Nick Newman and C. C. Mei from MIT.

Stephen Salter's 1974 invention became known as Salter's duck or nodding duck,

although it was officially referred to as the Edinburgh Duck. In small

scale controlled tests, the Duck's curved cam-like body can stop 90% of

wave motion and can convert 90% of that to electricity giving 81%

efficiency.

In the 1980s, as the oil price went down, wave-energy funding was

drastically reduced. Nevertheless, a few first-generation prototypes

were tested at sea. More recently, following the issue of climate

change, there is again a growing interest worldwide for renewable

energy, including wave energy.

The world's first marine energy test facility was established in

2003 to kick-start the development of a wave and tidal energy industry

in the UK. Based in Orkney, Scotland, the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC)

has supported the deployment of more wave and tidal energy devices than

at any other single site in the world. EMEC provides a variety of test

sites in real sea conditions. Its grid-connected wave test site is

situated at Billia Croo, on the western edge of the Orkney mainland, and

is subject to the full force of the Atlantic Ocean with seas as high as

19 metres recorded at the site. Wave energy developers currently

testing at the centre include Aquamarine Power, Pelamis Wave Power, ScottishPower Renewables and Wello.

Modern technology

Wave power devices are generally categorized by the method used to capture or harness the energy of the waves, by location and by the power take-off system. Locations are shoreline, nearshore and offshore. Types of power take-off include: hydraulic ram, elastomeric hose pump, pump-to-shore, hydroelectric turbine, air turbine, and linear electrical generator. When evaluating wave energy

as a technology type, it is important to distinguish between the four

most common approaches: point absorber buoys, surface attenuators,

oscillating water columns, and overtopping devices.

Generic

wave energy concepts: 1. Point absorber, 2. Attenuator, 3. Oscillating

wave surge converter, 4. Oscillating water column, 5. Overtopping

device, 6. Submerged pressure differential

Point absorber buoy

This device floats on the surface of the water,

held in place by cables connected to the seabed. The point-absorber is

defined as having a device width much smaller than the incoming

wavelength λ. A good point absorber has the same characteristics as a

good wave-maker. The wave energy is absorbed by radiating a wave with

destructive interference to the incoming waves. Buoys use the rise and

fall of swells to generate electricity in various ways including directly via linear generators, or via generators driven by mechanical linear-to-rotary converters or hydraulic pumps. EMF

generated by electrical transmission cables and acoustics of these

devices may be a concern for marine organisms. The presence of the buoys

may affect fish, marine mammals, and birds as potential minor collision

risk and roosting sites. Potential also exists for entanglement in

mooring lines. Energy removed from the waves may also affect the

shoreline, resulting in a recommendation that sites remain a

considerable distance from the shore.

Surface attenuator

These devices act similarly to point absorber buoys,

with multiple floating segments connected to one another and are

oriented perpendicular to incoming waves. A flexing motion is created by

swells that drive hydraulic pumps to generate electricity.

Environmental effects are similar to those of point absorber buoys, with

an additional concern that organisms could be pinched in the joints.

Oscillating wave surge converter

These devices typically have one end fixed to a structure or the seabed while the other end is free to move. Energy

is collected from the relative motion of the body compared to the fixed

point. Oscillating wave surge converters often come in the form of

floats, flaps, or membranes. Environmental concerns include minor risk

of collision, artificial reefing near the fixed point, EMF effects from subsea cables, and energy removal effecting sediment transport. Some of these designs incorporate parabolic reflectors

as a means of increasing the wave energy at the point of capture. These

capture systems use the rise and fall motion of waves to capture

energy. Once the wave energy is captured at a wave source, power must be carried to the point of use or to a connection to the electrical grid by transmission power cables.

Oscillating water column

Oscillating Water Column

devices can be located on shore or in deeper waters offshore. With an

air chamber integrated into the device, swells compress air in the

chambers forcing air through an air turbine to create electricity. Significant noise is produced as air is pushed through the turbines, potentially affecting birds and other marine organisms

within the vicinity of the device. There is also concern about marine

organisms getting trapped or entangled within the air chambers.

Overtopping device

Overtopping

devices are long structures that use wave velocity to fill a reservoir

to a greater water level than the surrounding ocean. The potential

energy in the reservoir height is then captured with low-head turbines.

Devices can be either on shore or floating offshore. Floating devices

will have environmental concerns about the mooring system affecting benthic organisms, organisms becoming entangled, or EMF effects produced from subsea cables. There is also some concern regarding low levels of turbine noise and wave energy removal affecting the nearfield habitat.

Submerged pressure differential

Submerged pressure differential based converters are a comparatively newer technology utilizing flexible (usually reinforced rubber) membranes to extract

wave energy. These converters use the difference in pressure at

different locations below a wave to produce a pressure difference within

a closed power take-off fluid system. This pressure difference is

usually used to produce flow, which drives a turbine and electrical

generator. Submerged pressure differential converters frequently use

flexible membranes as the working surface between the ocean and the

power take-off system. Membranes offer the advantage over rigid

structures of being compliant and low mass, which can produce more

direct coupling with the wave’s energy. Their compliant nature also

allows for large changes in the geometry of the working surface, which

can be used to tune the response of the converter for specific wave

conditions and to protect it from excessive loads in extreme conditions.

A submerged converter may be positioned either on the sea floor

or in midwater. In both cases, the converter is protected from water

impact loads which can occur at the free surface. Wave loads also diminish in non-linear

proportion to the distance below the free surface. This means that by

optimizing the depth of submergence for such a converter, a compromise

between protection from extreme loads and access to wave energy can be

found. Submerged WECs also have the potential to reduce the impact on

marine amenity and navigation, as they are not at the surface. Examples

of submerged pressure differential converters include M3 Wave, Bombora Wave Power's mWave, and CalWave.

Environmental effects

Common environmental concerns associated with marine energy developments include:

- The risk of marine mammals and fish being struck by tidal turbine blades;

- The effects of EMF and underwater noise emitted from operating marine energy devices;

- The physical presence of marine energy projects and their potential to alter the behavior of marine mammals, fish, and seabirds with attraction or avoidance;

- The potential effect on nearfield and farfield marine environment and processes such as sediment transport and water quality.

The Tethys database provides access to scientific literature and general information on the potential environmental effects of wave energy.

Potential

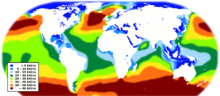

The worldwide resource of coastal wave energy has been estimated to be greater than 2 TW.

Locations with the most potential for wave power include the western

seaboard of Europe, the northern coast of the UK, and the Pacific

coastlines of North and South America, Southern Africa, Australia, and

New Zealand. The north and south temperate zones have the best sites for capturing wave power. The prevailing westerlies in these zones blow strongest in winter.

Estimates have been made by the National Renewable Energy

Laboratory (NREL) for various nations around the world in regards to the

amount of energy that could be generated from wave energy converters

(WECs) on their coastlines. For the United States in particular, it is

estimated that the total energy amount that could be generated along its

coastlines is equivalent to , which would account for nearly 33% of the total amount of energy consumed annually by the United States.

While this sounds promising, the coastline along Alaska accounted for

approx. 50% of the total energy created within this estimate.

Considering this, there would need to be the proper infrastructure in

place to transfer this energy from Alaskan shorelines to the mainland

United States in order to properly capitalize on meeting United States

energy demands. However, these numbers show the great potential these

technologies have if they are implemented on a global scale to satisfy

the search for sources of renewable energy.

WECs have gone under heavy examination through research,

especially relating to their efficiencies and the transport of the

energy they generate. NREL has shown that these WECs can have

efficiencies near 50%.

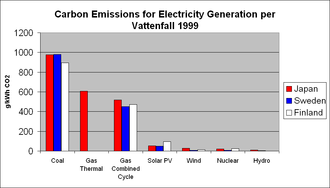

This is a phenomenal efficiency rating among renewable energy

production. For comparison, efficiencies above 10% in solar panels are

considered viable for sustainable energy production.

Thus, a value of 50% efficiency for a renewable energy source is

extremely viable for future development of renewable energy sources to

be implemented across the world. Additionally, research has been

conducted examining smaller WECs and their viability, especially

relating to power output. One piece of research showed great potential

with small devices, reminiscent of buoys, capable of generating upwards

of of power in various wave conditions and oscillations and device size (up to a roughly cylindrical 21 kg buoy).

Even further research has led to development of smaller, compact

versions of current WECs that could produce the same amount of energy

while using roughly one-half of the area necessary as current devices.

World wave energy resource map

Challenges

There

is a potential impact on the marine environment. Noise pollution, for

example, could have negative impact if not monitored, although the noise

and visible impact of each design vary greatly.[8]

Other biophysical impacts (flora and fauna, sediment regimes and water

column structure and flows) of scaling up the technology are being

studied.

In terms of socio-economic challenges, wave farms can result in the

displacement of commercial and recreational fishermen from productive

fishing grounds, can change the pattern of beach sand nourishment, and

may represent hazards to safe navigation.

Waves generate about 2,700 gigawatts of power. Of those 2,700

gigawatts, only about 500 gigawatts can be captured with current

technology.

Since 2008, Seabased Industry AB (SIAB) has deployed several units of

wave energy converters (WECs) manufactured with different designs.

Offshore deployments of WECs and underswater substation are being

complicated procedures. SIAB discussed these deployments in terms of

economy and time efficiency, as well as safety. Certain solutions are

suggested for the various problems encountered during the deployments.

It is found that the offshore deployment process can be optimized in

terms of cost, time efficiency and safety.

Wave farms

A group of wave energy devices deployed in the same location is called wave farm,

wave power farm or wave energy park. Wave farms represent a solution to

achieve larger electricity production. The devices of a park are going

to interact with each other hydrodynamically and electrically, according

to the number of machines, the distance among them, the geometric

layout, the wave climate, the local geometry, the control strategies.

The design process of a wave energy farm is a multi-optimization problem with the aim to get a high power production and low costs and power fluctuations.

Wave farm projects

United Kingdom

- The Islay LIMPET was installed and connected to the National Grid in 2000 and is the world's first commercial wave power installation

- Funding for a 3 MW wave farm in Scotland was announced on February 20, 2007, by the Scottish Executive, at a cost of over 4 million pounds, as part of a £13 million funding package for marine power in Scotland. The first machine was launched in May 2010.

- A facility known as Wave hub has been constructed off the north coast of Cornwall, England, to facilitate wave energy development. The Wave hub will act as giant extension cable, allowing arrays of wave energy generating devices to be connected to the electricity grid. The Wave hub will initially allow 20 MW of capacity to be connected, with potential expansion to 40 MW. Four device manufacturers have so far expressed interest in connecting to the Wave hub. The scientists have calculated that wave energy gathered at Wave Hub will be enough to power up to 7,500 households. The site has the potential to save greenhouse gas emissions of about 300,000 tons of carbon dioxide in the next 25 years.

- A 2017 study by Strathclyde University and Imperial College focused on the failure to develop "market ready" wave energy devices – despite a UK government push of over £200 million in the preceding 15 years – and how to improve the effectiveness of future government support.

Portugal

- The Aguçadoura Wave Farm was the world's first wave farm. It was located 5 km (3 mi) offshore near Póvoa de Varzim, north of Porto, Portugal. The farm was designed to use three Pelamis wave energy converters to convert the motion of the ocean surface waves into electricity, totalling to 2.25 MW in total installed capacity. The farm first generated electricity in July 2008 and was officially opened on September 23, 2008, by the Portuguese Minister of Economy. The wave farm was shut down two months after the official opening in November 2008 as a result of the financial collapse of Babcock & Brown due to the global economic crisis. The machines were off-site at this time due to technical problems, and although resolved have not returned to site and were subsequently scrapped in 2011 as the technology had moved on to the P2 variant as supplied to E.ON and Scottish Renewables. A second phase of the project planned to increase the installed capacity to 21 MW using a further 25 Pelamis machines is in doubt following Babcock's financial collapse.

Australia

- Bombora Wave Power is based in Perth, Western Australia and is currently developing the mWave flexible membrane converter. Bombora is currently preparing for a commercial pilot project in Peniche, Portugal.

- A CETO wave farm off the coast of Western Australia has been operating to prove commercial viability and, after preliminary environmental approval, underwent further development. In early 2015 a $100 million, multi megawatt system was connected to the grid, with all the electricity being bought to power HMAS Stirling naval base. Two fully submerged buoys which are anchored to the seabed, transmit the energy from the ocean swell through hydraulic pressure onshore; to drive a generator for electricity, and also to produce fresh water. As of 2015 a third buoy is planned for installation.[

- Ocean Power Technologies (OPT Australasia Pty Ltd) is developing a wave farm connected to the grid near Portland, Victoria through a 19 MW wave power station. The project has received an AU $66.46 million grant from the Federal Government of Australia.

- Oceanlinx will deploy a commercial scale demonstrator off the coast of South Australia at Port MacDonnell before the end of 2013. This device, the greenWAVE, has a rated electrical capacity of 1MW. This project has been supported by ARENA through the Emerging Renewables Program. The greenWAVE device is a bottom standing gravity structure, that does not require anchoring or seabed preparation and with no moving parts below the surface of the water.

United States

- Reedsport, Oregon – a commercial wave park on the west coast of the United States located 2.5 miles offshore near Reedsport, Oregon. The first phase of this project is for ten PB150 PowerBuoys, or 1.5 megawatts. The Reedsport wave farm was scheduled for installation spring 2013. In 2013, the project had ground to a halt because of legal and technical problems.

- Kaneohe Bay Oahu, Hawaii - Navy’s Wave Energy Test Site (WETS) currently testing the Azura wave power device. The Azura wave power device is 45-ton wave energy converter located at a depth of 30 (98 ft) in Kaneohe Bay.

Patents

- WIPO patent application WO2016032360 — 2016 Pumped-storage system – "Pressure buffering hydro power" patent application

- U.S. Patent 8,806,865 — 2011 Ocean wave energy harnessing device – Pelamis/Salter's Duck Hybrid patent

- U.S. Patent 3,928,967 — 1974 Apparatus and method of extracting wave energy – The original "Salter's Duck" patent

- U.S. Patent 4,134,023 — 1977 Apparatus for use in the extraction of energy from waves on water – Salter's method for improving "duck" efficiency

- U.S. Patent 6,194,815 — 1999 Piezoelectric rotary electrical energy generator

- Wave energy converters utilizing pressure differences US 20040217597 A1 — 2004 Wave energy converters utilizing pressure differences