In mathematics, taking the nth root is an operation involving two numbers, the radicand and the index or degree. Taking the nth root is written as , where x is the radicand and n is the index (also sometimes called the degree). This is pronounced as "the nth root of x". The definition then of an nth root of a number x is a number r (the root) which, when raised to the power of the positive integer n, yields x:

A root of degree 2 is called a square root (usually written without the n as just ) and a root of degree 3, a cube root (written ). Roots of higher degree are referred by using ordinal numbers, as in fourth root, twentieth root, etc. The computation of an nth root is a root extraction.

For example, 3 is a square root of 9, since 32 = 9, and −3 is also a square root of 9, since (−3)2 = 9.

Any non-zero number considered as a complex number has n different complex nth roots, including the real ones (at most two). The nth root of 0 is zero for all positive integers n, since 0n = 0. In particular, if n is even and x is a positive real number, one of its nth roots is real and positive, one is negative, and the others (when n > 2) are non-real complex numbers; if n is even and x is a negative real number, none of the nth roots are real. If n is odd and x is real, one nth root is real and has the same sign as x, while the other (n – 1) roots are not real. Finally, if x is not real, then none of its nth roots are real.

Roots of real numbers are usually written using the radical symbol or radix , with denoting the positive square root of x if x is positive; for higher roots, denotes the real nth root if n is odd, and the positive nth root if n is even and x is positive. In the other cases, the symbol is not commonly used as being ambiguous.

When complex nth roots are considered, it is often useful to choose one of the roots, called principal root, as a principal value. The common choice is to choose the principal nth root of x as the nth root with the greatest real part, and when there are two (for x real and negative), the one with a positive imaginary part. This makes the nth root a function that is real and positive for x real and positive, and is continuous in the whole complex plane, except for values of x that are real and negative.

A difficulty with this choice is that, for a negative real number and an odd index, the principal nth root is not the real one. For example, has three cube roots, , and The real cube root is and the principal cube root is

An unresolved root, especially one using the radical symbol, is sometimes referred to as a surd or a radical. Any expression containing a radical, whether it is a square root, a cube root, or a higher root, is called a radical expression, and if it contains no transcendental functions or transcendental numbers it is called an algebraic expression.

The positive root of a number is the inverse operation of Exponentiation with positive integer exponents.

Roots can also be defined as special cases of exponentiation, where the exponent is a fraction:Roots are used for determining the radius of convergence of a power series with the root test. The nth roots of 1 are called roots of unity and play a fundamental role in various areas of mathematics, such as number theory, theory of equations, and Fourier transform.

History

An archaic term for the operation of taking nth roots is radication.

Definition and notation

An nth root of a number x, where n is a positive integer, is any of the n real or complex numbers r whose nth power is x:

Every positive real number x has a single positive nth root, called the principal nth root, which is written . For n equal to 2 this is called the principal square root and the n is omitted. The nth root can also be represented using exponentiation as x1/n.

For even values of n, positive numbers also have a negative nth root, while negative numbers do not have a real nth root. For odd values of n, every negative number x has a real negative nth root. For example, −2 has a real 5th root, but −2 does not have any real 6th roots.

Every non-zero number x, real or complex, has n different complex number nth roots. (In the case x is real, this count includes any real nth roots.) The only complex root of 0 is 0.

The nth roots of almost all numbers (all integers except the nth powers, and all rationals except the quotients of two nth powers) are irrational. For example,

All nth roots of rational numbers are algebraic numbers, and all nth roots of integers are algebraic integers.

The term "surd" traces back to Al-Khwarizmi (c. 825), who referred to rational and irrational numbers as audible and inaudible, respectively. This later led to the Arabic word "أصم" (asamm, meaning "deaf" or "dumb") for irrational number being translated into Latin as surdus (meaning "deaf" or "mute"). Gerard of Cremona (c. 1150), Fibonacci (1202), and then Robert Recorde (1551) all used the term to refer to unresolved irrational roots, that is, expressions of the form in which and are integer numerals and the whole expression denotes an irrational number. Irrational numbers of the form where is rational, are called pure quadratic surds; irrational numbers of the form where and are rational, are called mixed quadratic surds.

Square roots

A square root of a number x is a number r which, when squared, becomes x:

Every positive real number has two square roots, one positive and one negative. For example, the two square roots of 25 are 5 and −5. The positive square root is also known as the principal square root, and is denoted with a radical sign:

Since the square of every real number is nonnegative, negative numbers do not have real square roots. However, for every negative real number there are two imaginary square roots. For example, the square roots of −25 are 5i and −5i, where i represents a number whose square is −1.

Cube roots

A cube root of a number x is a number r whose cube is x:

Every real number x has exactly one real cube root, written . For example,

- and

Every real number has two additional complex cube roots.

Identities and properties

Expressing the degree of an nth root in its exponent form, as in , makes it easier to manipulate powers and roots. If is a non-negative real number,

Every non-negative number has exactly one non-negative real nth root, and so the rules for operations with surds involving non-negative radicands and are straightforward within the real numbers:

Subtleties can occur when taking the nth roots of negative or complex numbers. For instance:

- but, rather,

Since the rule strictly holds for non-negative real radicands only, its application leads to the inequality in the first step above.

Simplified form of a radical expression

A non-nested radical expression is said to be in simplified form if no factor of the radicand can be written as a power greater than or equal to the index; there are no fractions inside the radical sign; and there are no radicals in the denominator.

For example, to write the radical expression in simplified form, we can proceed as follows. First, look for a perfect square under the square root sign and remove it:

Next, there is a fraction under the radical sign, which we change as follows:

Finally, we remove the radical from the denominator as follows:

When there is a denominator involving surds it is always possible to find a factor to multiply both numerator and denominator by to simplify the expression.[9][10] For instance using the factorization of the sum of two cubes:

Simplifying radical expressions involving nested radicals can be quite difficult. In particular, denesting is not always possible, and when possible, it may involve advanced Galois theory. Moreover, when complete denesting is impossible, there is no general canonical form such that the equality of two numbers can be tested by simply looking at their canonical expressions.

For example, it is not obvious that

The above can be derived through:

Let , with p and q coprime and positive integers. Then is rational if and only if both and are integers, which means that both p and q are nth powers of some integer.

Infinite series

The radical or root may be represented by the infinite series:

with . This expression can be derived from the binomial series.

Computing principal roots

Using Newton's method

The nth root of a number A can be computed with Newton's method, which starts with an initial guess x0 and then iterates using the recurrence relation

until the desired precision is reached. For computational efficiency, the recurrence relation is commonly rewritten

Or even more compact with only two divisions as

This allows to have only one exponentiation, and to compute once for all the first factor of each term.

For example, to find the fifth root of 34, we plug in n = 5, A = 34 and x0 = 2 (initial guess). The first 5 iterations are, approximately:

x0 = 2

x1 = 2.025

x2 = 2.02439 7...

x3 = 2.02439 7458...

x4 = 2.02439 74584 99885 04251 08172...

x5 = 2.02439 74584 99885 04251 08172 45541 93741 91146 21701 07311 8...

(All correct digits shown.)

The approximation x4 is accurate to 25 decimal places and x5 is good for 51.

Newton's method can be modified to produce various generalized continued fractions for the nth root. For example,

Digit-by-digit calculation of principal roots of decimal (base 10) numbers

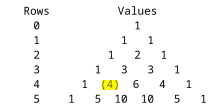

Building on the digit-by-digit calculation of a square root, it can be seen that the formula used there, , or , follows a pattern involving Pascal's triangle. For the nth root of a number is defined as the value of element in row of Pascal's Triangle such that , we can rewrite the expression as . For convenience, call the result of this expression . Using this more general expression, any positive principal root can be computed, digit-by-digit, as follows.

Write the original number in decimal form. The numbers are written similar to the long division algorithm, and, as in long division, the root will be written on the line above. Now separate the digits into groups of digits equating to the root being taken, starting from the decimal point and going both left and right. The decimal point of the root will be above the decimal point of the radicand. One digit of the root will appear above each group of digits of the original number.

Beginning with the left-most group of digits, do the following procedure for each group:

- Starting on the left, bring down the most significant (leftmost) group of digits not yet used (if all the digits have been used, write "0" the number of times required to make a group) and write them to the right of the remainder from the previous step (on the first step, there will be no remainder). In other words, multiply the remainder by and add the digits from the next group. This will be the current value c.

- Find p and x, as follows:

- Let be the part of the root found so far, ignoring any decimal point. (For the first step, and ).

- Determine the greatest digit such that .

- Place the digit as the next digit of the root, i.e., above the group of digits you just brought down. Thus the next p will be the old p times 10 plus x.

- Subtract from to form a new remainder.

- If the remainder is zero and there are no more digits to bring down, then the algorithm has terminated. Otherwise go back to step 1 for another iteration.

Examples

Find the square root of 152.2756.

1 2. 3 4

/

\/ 01 52.27 56 (Results) (Explanations)

01 x = 1 100·1·00·12 + 101·2·01·11 ≤ 1 < 100·1·00·22 + 101·2·01·21

01 y = 1 y = 100·1·00·12 + 101·2·01·11 = 1 + 0 = 1

00 52 x = 2 100·1·10·22 + 101·2·11·21 ≤ 52 < 100·1·10·32 + 101·2·11·31

00 44 y = 44 y = 100·1·10·22 + 101·2·11·21 = 4 + 40 = 44

08 27 x = 3 100·1·120·32 + 101·2·121·31 ≤ 827 < 100·1·120·42 + 101·2·121·41

07 29 y = 729 y = 100·1·120·32 + 101·2·121·31 = 9 + 720 = 729

98 56 x = 4 100·1·1230·42 + 101·2·1231·41 ≤ 9856 < 100·1·1230·52 + 101·2·1231·51

98 56 y = 9856 y = 100·1·1230·42 + 101·2·1231·41 = 16 + 9840 = 9856

00 00

Algorithm terminates: Answer is 12.34

Find the cube root of 4192 truncated to the nearest thousandth.

1 6. 1 2 4

3 /

\/ 004 192.000 000 000 (Results) (Explanations)

004 x = 1 100·1·00·13 + 101·3·01·12 + 102·3·02·11 ≤ 4 < 100·1·00·23 + 101·3·01·22 + 102·3·02·21

001 y = 1 y = 100·1·00·13 + 101·3·01·12 + 102·3·02·11 = 1 + 0 + 0 = 1

003 192 x = 6 100·1·10·63 + 101·3·11·62 + 102·3·12·61 ≤ 3192 < 100·1·10·73 + 101·3·11·72 + 102·3·12·71

003 096 y = 3096 y = 100·1·10·63 + 101·3·11·62 + 102·3·12·61 = 216 + 1,080 + 1,800 = 3,096

096 000 x = 1 100·1·160·13 + 101·3·161·12 + 102·3·162·11 ≤ 96000 < 100·1·160·23 + 101·3·161·22 + 102·3·162·21

077 281 y = 77281 y = 100·1·160·13 + 101·3·161·12 + 102·3·162·11 = 1 + 480 + 76,800 = 77,281

018 719 000 x = 2 100·1·1610·23 + 101·3·1611·22 + 102·3·1612·21 ≤ 18719000 < 100·1·1610·33 + 101·3·1611·32 + 102·3·1612·31

015 571 928 y = 15571928 y = 100·1·1610·23 + 101·3·1611·22 + 102·3·1612·21 = 8 + 19,320 + 15,552,600 = 15,571,928

003 147 072 000 x = 4 100·1·16120·43 + 101·3·16121·42 + 102·3·16122·41 ≤ 3147072000 < 100·1·16120·53 + 101·3·16121·52 + 102·3·16122·51

The desired precision is achieved. The cube root of 4192 is 16.124...

Logarithmic calculation

The principal nth root of a positive number can be computed using logarithms. Starting from the equation that defines r as an nth root of x, namely with x positive and therefore its principal root r also positive, one takes logarithms of both sides (any base of the logarithm will do) to obtain

The root r is recovered from this by taking the antilog:

(Note: That formula shows b raised to the power of the result of the division, not b multiplied by the result of the division.)

For the case in which x is negative and n is odd, there is one real root r which is also negative. This can be found by first multiplying both sides of the defining equation by −1 to obtain then proceeding as before to find |r|, and using r = −|r|.

Geometric constructibility

The ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to use compass and straightedge to construct a length equal to the square root of a given length, when an auxiliary line of unit length is given. In 1837 Pierre Wantzel proved that an nth root of a given length cannot be constructed if n is not a power of 2.

Complex roots

Every complex number other than 0 has n different nth roots.

Square roots

The two square roots of a complex number are always negatives of each other. For example, the square roots of −4 are 2i and −2i, and the square roots of i are

If we express a complex number in polar form, then the square root can be obtained by taking the square root of the radius and halving the angle:

A principal root of a complex number may be chosen in various ways, for example

which introduces a branch cut in the complex plane along the positive real axis with the condition 0 ≤ θ < 2π, or along the negative real axis with −π < θ ≤ π.

Using the first(last) branch cut the principal square root maps to the half plane with non-negative imaginary(real) part. The last branch cut is presupposed in mathematical software like Matlab or Scilab.

Roots of unity

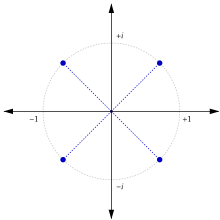

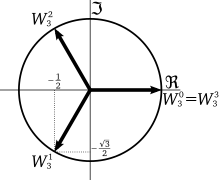

The number 1 has n different nth roots in the complex plane, namely

where

These roots are evenly spaced around the unit circle in the complex plane, at angles which are multiples of . For example, the square roots of unity are 1 and −1, and the fourth roots of unity are 1, , −1, and .

nth roots

Every complex number has n different nth roots in the complex plane. These are

where η is a single nth root, and 1, ω, ω2, ... ωn−1 are the nth roots of unity. For example, the four different fourth roots of 2 are

In polar form, a single nth root may be found by the formula

Here r is the magnitude (the modulus, also called the absolute value) of the number whose root is to be taken; if the number can be written as a+bi then . Also, is the angle formed as one pivots on the origin counterclockwise from the positive horizontal axis to a ray going from the origin to the number; it has the properties that and

Thus finding nth roots in the complex plane can be segmented into two steps. First, the magnitude of all the nth roots is the nth root of the magnitude of the original number. Second, the angle between the positive horizontal axis and a ray from the origin to one of the nth roots is , where is the angle defined in the same way for the number whose root is being taken. Furthermore, all n of the nth roots are at equally spaced angles from each other.

If n is even, a complex number's nth roots, of which there are an even number, come in additive inverse pairs, so that if a number r1 is one of the nth roots then r2 = –r1 is another. This is because raising the latter's coefficient –1 to the nth power for even n yields 1: that is, (–r1)n = (–1)n × r1n = r1n.

As with square roots, the formula above does not define a continuous function over the entire complex plane, but instead has a branch cut at points where θ / n is discontinuous.

Solving polynomials

It was once conjectured that all polynomial equations could be solved algebraically (that is, that all roots of a polynomial could be expressed in terms of a finite number of radicals and elementary operations). However, while this is true for third degree polynomials (cubics) and fourth degree polynomials (quartics), the Abel–Ruffini theorem (1824) shows that this is not true in general when the degree is 5 or greater. For example, the solutions of the equation

cannot be expressed in terms of radicals. (cf. quintic equation)

Proof of irrationality for non-perfect nth power x

Assume that is rational. That is, it can be reduced to a fraction , where a and b are integers without a common factor.

This means that .

Since x is an integer, and must share a common factor if . This means that if , is not in simplest form. Thus b should equal 1.

Since and , .

This means that and thus, . This implies that is an integer. Since x is not a perfect nth power, this is impossible. Thus is irrational.

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7b3ba2638d05cd9ed8dafae7e34986399e48ea99)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a55f866116e7a86823816615dd98fcccde75473)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{5}]{-2}}=-1.148698354\ldots }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/98d22c0a8f77736a738e9566bd1ebd1b46438ffb)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{r}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7239a99d467e14f95c82664b252cc163da672fb7)

![{\displaystyle y={\sqrt[{3}]{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/be50c0a49b200fb46800951d0268b0a9d4e3fdda)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{8}}=2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1f378331b0d609846c021c1a0bbff0a4fc1755c3)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{-8}}=-2.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7378906b2e4dc7e0d132636adef3166ed829537f)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{a^{m}}}=(a^{m})^{1/n}=a^{m/n}=(a^{1/n})^{m}=({\sqrt[{n}]{a}})^{m}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/db6ea037832c3df199f25395b7043ea18927905b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\sqrt[{n}]{ab}}&={\sqrt[{n}]{a}}{\sqrt[{n}]{b}}\\{\sqrt[{n}]{\frac {a}{b}}}&={\frac {\sqrt[{n}]{a}}{\sqrt[{n}]{b}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1b645cc98d9626d9b49b01acfb20f4a5efb3abf)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{a}}\times {\sqrt[{n}]{b}}={\sqrt[{n}]{ab}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7d0a49ffbfd95598ffe89e29489a3d475de5fb58)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{{\sqrt[{3}]{a}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{b}}}}={\frac {{\sqrt[{3}]{a^{2}}}-{\sqrt[{3}]{ab}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{b^{2}}}}{\left({\sqrt[{3}]{a}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{b}}\right)\left({\sqrt[{3}]{a^{2}}}-{\sqrt[{3}]{ab}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{b^{2}}}\right)}}={\frac {{\sqrt[{3}]{a^{2}}}-{\sqrt[{3}]{ab}}+{\sqrt[{3}]{b^{2}}}}{a+b}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4432a6ac651c0cc085a2d15cf3b00d4a9a895ca6)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{r}}={\sqrt[{n}]{p}}/{\sqrt[{n}]{q}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32f9eceaf6392a34ca84e490204f6eef56b4a7be)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{p}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dac134c13bde44d42060499220adf6949490f40e)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{q}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3dfc3fcfbe3811c3e980414f3a6c90ca7c286ef6)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{z}}={\sqrt[{n}]{x^{n}+y}}=x+{\cfrac {y}{nx^{n-1}+{\cfrac {(n-1)y}{2x+{\cfrac {(n+1)y}{3nx^{n-1}+{\cfrac {(2n-1)y}{2x+{\cfrac {(2n+1)y}{5nx^{n-1}+{\cfrac {(3n-1)y}{2x+\ddots }}}}}}}}}}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5eda4375d928606c0aa597ff64902c6fcc45f364)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{4}]{2}},\quad i{\sqrt[{4}]{2}},\quad -{\sqrt[{4}]{2}},\quad {\text{and}}\quad -i{\sqrt[{4}]{2}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/634ba9f9880a52a0ebdd648e6cf1d8979c3f63ca)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{re^{i\theta }}}={\sqrt[{n}]{r}}\cdot e^{i\theta /n}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb634da6a458c0fdff9deb78d393ff2791ab3b7c)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{x}}=a}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/39c0048b93aee48d4f00d14b120a98c1fbbcc67d)