| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | ACh |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | motor neurons, parasympathetic nervous system, brain |

| Target tissues | skeletal muscles, brain, many other organs |

| Receptors | nicotinic, muscarinic |

| Agonists | nicotine, muscarine, cholinesterase inhibitors |

| Antagonists | tubocurarine, atropine |

| Precursor | choline, acetyl-CoA |

| Biosynthesis | choline acetyltransferase |

| Metabolism | acetylcholinesterase |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| E number | E1001(i) (additional chemicals) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.118 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H16NO2 |

| Molar mass | 146.210 g·mol−1 |

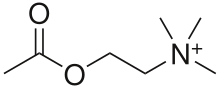

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic chemical that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (and humans) as a neurotransmitter—a chemical message released by nerve cells to send signals to other cells, such as neurons, muscle cells and gland cells. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Parts in the body that use or are affected by acetylcholine are referred to as cholinergic. Substances that interfere with acetylcholine activity are called anticholinergics.

Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter used at the neuromuscular junction—in other words, it is the chemical that motor neurons of the nervous system release in order to activate muscles. This property means that drugs that affect cholinergic systems can have very dangerous effects ranging from paralysis to convulsions. Acetylcholine is also a neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system, both as an internal transmitter for the sympathetic nervous system and as the final product released by the parasympathetic nervous system. Acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter of the parasympathetic nervous systems.

In the brain, acetylcholine functions as a neurotransmitter and as a neuromodulator. The brain contains a number of cholinergic areas, each with distinct functions; such as playing an important role in arousal, attention, memory and motivation.

Acetylcholine (ACh), has also been traced in cells of non-neural origins and microbes. Recently, enzymes related to its synthesis, degradation and cellular uptake have been traced back to early origins of unicellular eukaryotes. The protist pathogen Acanthamoeba spp. has shown the presence of ACh, which provides growth and proliferative signals via a membrane located M1-muscarinic receptor homolog.

Partly because of its muscle-activating function, but also because of its functions in the autonomic nervous system and brain, many important drugs exert their effects by altering cholinergic transmission. Numerous venoms and toxins produced by plants, animals, and bacteria, as well as chemical nerve agents such as Sarin, cause harm by inactivating or hyperactivating muscles via their influences on the neuromuscular junction. Drugs that act on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, such as atropine, can be poisonous in large quantities, but in smaller doses they are commonly used to treat certain heart conditions and eye problems. Scopolamine, which acts mainly on muscarinic receptors in the brain, can cause delirium and amnesia. The addictive qualities of nicotine are derived from its effects on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.

Chemistry

Acetylcholine is a choline molecule that has been acetylated at the oxygen atom. Because of the presence of a highly polar, charged ammonium

group, acetylcholine does not penetrate lipid membranes. Because of

this, when the drug is introduced externally, it remains in the

extracellular space and does not pass through the blood–brain barrier. A

synonym of this drug is miochol.

Biochemistry

Acetylcholine is synthesized in certain neurons by the enzyme choline acetyltransferase from the compounds choline and acetyl-CoA.

Cholinergic neurons are capable of producing ACh. An example of a

central cholinergic area is the nucleus basalis of Meynert in the basal

forebrain.

The enzyme acetylcholinesterase converts acetylcholine into the inactive metabolites choline and acetate.

This enzyme is abundant in the synaptic cleft, and its role in rapidly

clearing free acetylcholine from the synapse is essential for proper

muscle function. Certain neurotoxins work by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, thus leading to excess acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, causing paralysis of the muscles needed for breathing and stopping the beating of the heart.

Functions

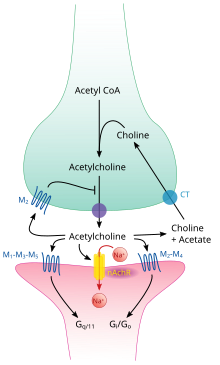

Acetylcholine pathway.

functions in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). In the CNS, cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus support the cognitive

functions of those target areas. In the PNS, acetylcholine activates

muscles and is a major neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system.

Cellular effects

Acetylcholine processing in a synapse. After release acetylcholine is broken down by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.

Like many other biologically active substances, acetylcholine exerts its effects by binding to and activating receptors located on the surface of cells. There are two main classes of acetylcholine receptor, nicotinic and muscarinic. They are named for chemicals that can selectively activate each type of receptor without activating the other: muscarine is a compound found in the mushroom Amanita muscaria; nicotine is found in tobacco.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are ligand-gated ion channels permeable to sodium, potassium, and calcium

ions. In other words, they are ion channels embedded in cell membranes,

capable of switching from a closed to an open state when acetylcholine

binds to them; in the open state they allow ions to pass through.

Nicotinic receptors come in two main types, known as muscle-type and

neuronal-type. The muscle-type can be selectively blocked by curare, the neuronal-type by hexamethonium.

The main location of muscle-type receptors is on muscle cells, as

described in more detail below. Neuronal-type receptors are located in

autonomic ganglia (both sympathetic and parasympathetic), and in the

central nervous system.

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

have a more complex mechanism, and affect target cells over a longer

time frame. In mammals, five subtypes of muscarinic receptors have been

identified, labeled M1 through M5. All of them function as G protein-coupled receptors, meaning that they exert their effects via a second messenger system. The M1, M3, and M5 subtypes are Gq-coupled; they increase intracellular levels of IP3 and calcium by activating phospholipase C. Their effect on target cells is usually excitatory. The M2 and M4 subtypes are Gi/Go-coupled; they decrease intracellular levels of cAMP by inhibiting adenylate cyclase.

Their effect on target cells is usually inhibitory. Muscarinic

acetylcholine receptors are found in both the central nervous system and

the peripheral nervous system of the heart, lungs, upper

gastrointestinal tract, and sweat glands.

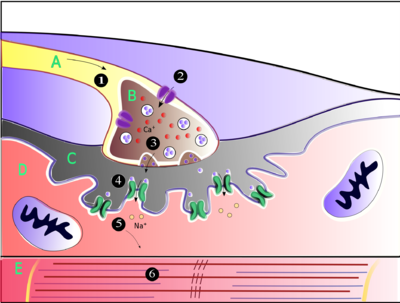

Neuromuscular junction

Muscles

contract when they receive signals from motor neurons. The

neuromuscular junction is the site of the signal exchange. The steps of

this process in vertebrates occur as follows: (1) The action potential

reaches the axon terminal. (2) Calcium ions flow into the axon terminal.

(3) Acetylcholine is released into the synaptic cleft.

(4) Acetylcholine binds to postsynaptic receptors. (5) This binding

causes ion channels to open and allows sodium ions to flow into the

muscle cell. (6) The flow of sodium ions across the membrane into the

muscle cell generates an action potential which induces muscle

contraction. Labels: A: Motor neuron axon B: Axon terminal C: Synaptic

cleft D: Muscle cell E: Part of a Myofibril

Acetylcholine is the substance the nervous system uses to activate skeletal muscles, a kind of striated muscle. These are the muscles used for all types of voluntary movement, in contrast to smooth muscle tissue,

which is involved in a range of involuntary activities such as movement

of food through the gastrointestinal tract and constriction of blood

vessels. Skeletal muscles are directly controlled by motor neurons located in the spinal cord or, in a few cases, the brainstem. These motor neurons send their axons through motor nerves, from which they emerge to connect to muscle fibers at a special type of synapse called the neuromuscular junction.

When a motor neuron generates an action potential,

it travels rapidly along the nerve until it reaches the neuromuscular

junction, where it initiates an electrochemical process that causes

acetylcholine to be released into the space between the presynaptic

terminal and the muscle fiber. The acetylcholine molecules then bind to

nicotinic ion-channel receptors on the muscle cell membrane, causing the

ion channels to open. Sodium ions then flow into the muscle cell,

initiating a sequence of steps that finally produce muscle contraction.

Factors that decrease release of acetylcholine (and thereby affecting P-type calcium channels):

- Antibiotics (clindamycin, polymyxin)

- Magnesium: antagonizes P-type calcium channels

- Hypocalcemia

- Anticonvulsants

- Diuretics (furosemide)

- Eaton-Lambert syndrome: inhibits P-type calcium channels

- Botulinum toxin: inhibits SNARE proteins

- Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, diltiazem) do not affect P-channels. These drugs affect L-type calcium channels.

Autonomic nervous system

Components and connections of the parasympathetic nervous system.

The autonomic nervous system controls a wide range of involuntary and unconscious body functions. Its main branches are the sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system.

Broadly speaking, the function of the sympathetic nervous system is to

mobilize the body for action; the phrase often invoked to describe it is

fight-or-flight.

The function of the parasympathetic nervous system is to put the body

in a state conducive to rest, regeneration, digestion, and reproduction;

the phrase often invoked to describe it is "rest and digest" or "feed

and breed". Both of these aforementioned systems use acetylcholine, but

in different ways.

At a schematic level, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous

systems are both organized in essentially the same way: preganglionic

neurons in the central nervous system send projections to neurons

located in autonomic ganglia, which send output projections to virtually

every tissue of the body. In both branches the internal connections,

the projections from the central nervous system to the autonomic

ganglia, use acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter to innervate (or

excite) ganglia neurons. In the parasympathetic nervous system the

output connections, the projections from ganglion neurons to tissues

that don't belong to the nervous system, also release acetylcholine but

act on muscarinic receptors. In the sympathetic nervous system the

output connections mainly release noradrenaline, although acetylcholine is released at a few points, such as the sudomotor innervation of the sweat glands.

Direct vascular effects

Acetylcholine in the serum exerts a direct effect on vascular tone by binding to muscarinic receptors present on vascular endothelium. These cells respond by increasing production of nitric oxide, which signals the surrounding smooth muscle to relax, leading to vasodilation.

Central nervous system

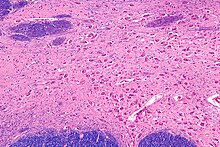

Micrograph of the nucleus basalis (of Meynert), which produces acetylcholine in the CNS. LFB-HE stain.

In the central nervous system, ACh has a variety of effects on plasticity, arousal and reward. ACh has an important role in the enhancement of alertness when we wake up, in sustaining attention and in learning and memory.

Damage to the cholinergic (acetylcholine-producing) system in the

brain has been shown to be associated with the memory deficits

associated with Alzheimer's disease. ACh has also been shown to promote REM sleep.

In the brainstem acetylcholine originates from the Pedunculopontine nucleus and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus collectively known as the mesopontine tegmentum area or pontomesencephalotegmental complex. In the basal forebrain, it originates from the basal nucleus of Meynert and medial septal nucleus:

- The pontomesencephalotegmental complex acts mainly on M1 receptors in the brainstem, deep cerebellar nuclei, pontine nuclei, locus coeruleus, raphe nucleus, lateral reticular nucleus and inferior olive. It also projects to the thalamus, tectum, basal ganglia and basal forebrain.

- Basal nucleus of Meynert acts mainly on M1 receptors in the neocortex.

- Medial septal nucleus acts mainly on M1 receptors in the hippocampus and parts of the cerebral cortex.

In addition, ACh acts as an important internal transmitter in the striatum, which is part of the basal ganglia. It is released by cholinergic interneurons.

In humans, non-human primates and rodents, these interneurons respond

to salient environmental stimuli with responses that are temporally

aligned with the responses of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra.

Memory

Acetylcholine has been implicated in learning and memory in several ways. The anticholinergic drug, scopolamine, impairs acquisition of new information in humans and animals. In animals, disruption of the supply of acetylcholine to the neocortex impairs the learning of simple discrimination tasks, comparable to the acquisition of factual information and disruption of the supply of acetylcholine to the hippocampus and adjacent cortical areas produces forgetting comparable to anterograde amnesia in humans.

Diseases and disorders

Myasthenia gravis

The disease myasthenia gravis, characterized by muscle weakness and fatigue, occurs when the body inappropriately produces antibodies

against acetylcholine nicotinic receptors, and thus inhibits proper

acetylcholine signal transmission. Over time, the motor end plate is

destroyed. Drugs that competitively inhibit acetylcholinesterase (e.g.,

neostigmine, physostigmine, or primarily pyridostigmine) are effective

in treating this disorder. They allow endogenously released

acetylcholine more time to interact with its respective receptor before

being inactivated by acetylcholinesterase in the synaptic cleft (the

space between nerve and muscle).

Pharmacology

Blocking,

hindering or mimicking the action of acetylcholine has many uses in

medicine. Drugs acting on the acetylcholine system are either agonists

to the receptors, stimulating the system, or antagonists, inhibiting it.

Acetylcholine receptor agonists and antagonists can either have an

effect directly on the receptors or exert their effects indirectly,

e.g., by affecting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which degrades the receptor ligand. Agonists increase the level of receptor activation, antagonists reduce it.

Acetylcholine itself does not have therapeutic value as a drug

for intravenous administration because of its multi-faceted action

(non-selective) and rapid inactivation by cholinesterase. However, it is

used in the form of eye drops to cause constriction of the pupil during

cataract surgery, which facilitates quick post-operational recovery.

Nicotinic receptors

Nicotine binds to and activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, mimicking the effect of acetylcholine at these receptors. When ACh interacts with a nicotinic ACh receptor, it opens a Na+ channel and Na+

ions flow into the membrane. This causes a depolarization, and results

in an excitatory post-synaptic potential. Thus, ACh is excitatory on

skeletal muscle; the electrical response is fast and short-lived. Curares are arrow poisons, which act at nicotinic receptors and have been used to develop clinically useful therapies.

Muscarinic receptors

Atropine is a non-selective competitive antagonist with Acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors.

Cholinesterase inhibitors

Many ACh receptor agonists work indirectly by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.

The resulting accumulation of acetylcholine causes continuous

stimulation of the muscles, glands, and central nervous system, which

can result in fatal convulsions if the dose is high.

They are examples of enzyme inhibitors, and increase the action of acetylcholine by delaying its degradation; some have been used as nerve agents (Sarin and VX nerve gas) or pesticides (organophosphates and the carbamates).

Many toxins and venoms produced by plants and animals also contain

cholinesterase inhibitors. In clinical use, they are administered in low

doses to reverse the action of muscle relaxants, to treat myasthenia gravis, and to treat symptoms of Alzheimer's disease (rivastigmine, which increases cholinergic activity in the brain).

Synthesis inhibitors

Organic mercurial compounds, such as methylmercury, have a high affinity for sulfhydryl groups,

which causes dysfunction of the enzyme choline acetyltransferase. This

inhibition may lead to acetylcholine deficiency, and can have

consequences on motor function.

Release inhibitors

Botulinum toxin (Botox) acts by suppressing the release of acetylcholine, whereas the venom from a black widow spider (alpha-latrotoxin) has the reverse effect. ACh inhibition causes paralysis. When bitten by a black widow spider, one experiences the wastage of ACh supplies and the muscles begin to contract. If and when the supply is depleted, paralysis occurs.

Comparative biology and evolution

Acetylcholine

is used by organisms in all domains of life for a variety of purposes.

It is believed that choline, a precursor to acetylcholine, was used by

single celled organisms billions of years ago for synthesizing cell membrane phospholipids.

Following the evolution of choline transporters, the abundance of

intracellular choline paved the way for choline to become incorporated

into other synthetic pathways, including acetylcholine production.

Acetylcholine is used by bacteria, fungi, and a variety of other

animals. Many of the uses of acetylcholine rely on its action on ion

channels via GPCRs like membrane proteins.

The two major types of acetylcholine receptors, muscarinic and

nicotinic receptors, have convergently evolved to be responsive to

acetylcholine. This means that rather than having evolved from a common

homolog, these receptors evolved from separate receptor families. It is

estimated that the nicotinic receptor family dates back longer than 2.5

billion years.

Likewise, muscarinic receptors are thought to have diverged from other

GPCRs at least 0.5 billion years ago. Both of these receptor groups have

evolved numerous subtypes with unique ligand affinities and signaling

mechanisms. The diversity of the receptor types enables acetylcholine to

create varying responses depending on which receptor types are

activated, and allow for acetylcholine to dynamically regulate

physiological processes.

History

In 1867, Adolf von Baeyer resolved the structures of choline and acetylcholine and synthetized them both, referring to the latter as "acetylneurin" in the study. Choline is a precursor for acetylcholine. This is why Frederick Walker Mott and William Dobinson Halliburton noted in 1899 that choline injections decreased the blood pressure of animals. Acetylcholine was noted to be biologically active in 1906, when Reid Hunt (1870–1948) and René de M. Taveau found that it decreased blood pressure in exceptionally tiny doses.

In 1914, Arthur J. Ewins was to first to extract acetylcholine from nature. He identified it as the blood pressure decreasing contaminant from some Claviceps purpurea ergot extracts, by the request of Henry Hallett Dale.

Later in 1914, Dale outlined the effects of acetylcholine at various

types of peripheral synapses and also noted that it lowered the blood

pressure of cats via subcutaneous injections even at doses of one nanogram.

The concept neurotransmitters was unknown before 1921, when Otto Loewi noted that the vagus nerve secreted a substance that stimulated the heart muscle whilst working as a professor in the University of Graz. He named it vagusstoff ("vagus substance"), noted it to be a structural analog of choline and suspected it to be acetylcholine.

In 1926, Loewi and E. Navratil deduced that the compound is probably

acetylcholine, as vagusstoff and synthetic acetylcholine lost their

activity in a similar manner when in contact with tissue lysates that contained acetylcholine-degrading enzymes (now known to be cholinesterases). This conclusion was accepted widely. Later studies confirmed the function of acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter.

In 1936, H. H. Dale and O. Loewi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their studies relating to acetylcholine and nerve impulses.