The three-age system is the periodization of history into three time periods;

for example: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age; although it also refers to other tripartite divisions of historic time periods. In history, archaeology and physical anthropology,

the three-age system is a methodological concept adopted during the

19th century by which artifacts and events of late prehistory and early

history could be ordered into a recognizable chronology. It was

initially developed by C. J. Thomsen, director of the Royal Museum of Nordic Antiquities, Copenhagen, as a means to classify the museum's collections according to whether the artifacts were made of stone, bronze, or iron.

The system first appealed to British researchers working in the science of ethnology who adopted it to establish race sequences for Britain's past based on cranial types. Although the craniological ethnology that formed its first scholarly context holds no scientific value, the relative chronology of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age is still in use in a general public context, and the three ages remain the underpinning of prehistoric chronology for Europe, the Mediterranean world and the Near East.

The structure reflects the cultural and historical background of

Mediterranean Europe and the Middle East and soon underwent further

subdivisions, including the 1865 partitioning of the Stone Age into Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods by John Lubbock.

It is, however, of little or no use for the establishment of

chronological frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa, much of Asia, the

Americas and some other areas and has little importance in contemporary

archaeological or anthropological discussion for these regions.

Origin

The

concept of dividing pre-historical ages into systems based on metals

extends far back in European history, probably originated by Lucretius

in the first century BC. But the present archaeological system of the

three main ages—stone, bronze and iron—originates with the Danish

archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

(1788–1865), who placed the system on a more scientific basis by

typological and chronological studies, at first, of tools and other artifacts present in the Museum of Northern Antiquities in Copenhagen (later the National Museum of Denmark).

He later used artifacts and the excavation reports published or sent to

him by Danish archaeologists who were doing controlled excavations. His

position as curator of the museum gave him enough visibility to become

highly influential on Danish archaeology. A well-known and well-liked

figure, he explained his system in person to visitors at the museum,

many of them professional archaeologists.

The Metallic Ages of Hesiod

Hesiod inspired by the Muse, Gustave Moreau, 1891

In his poem, Works and Days, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod possibly between 750 and 650 BC, defined five successive Ages of Man: 1. Golden, 2. Silver, 3. Bronze, 4. Heroic and 5. Iron. Only the Bronze Age and the Iron Age are based on the use of metal:

... then Zeus the father created the third generation of mortals, the age of bronze ... They were terrible and strong, and the ghastly action of Ares was theirs, and violence. ... The weapons of these men were bronze, of bronze their houses, and they worked as bronzesmiths. There was not yet any black iron.

Hesiod knew from the traditional poetry, such as the Iliad,

and the heirloom bronze artifacts that abounded in Greek society, that

before the use of iron to make tools and weapons, bronze had been the

preferred material and iron was not smelted at all. He did not continue

the manufacturing metaphor, but mixed his metaphors, switching over to

the market value of each metal. Iron was cheaper than bronze, so there

must have been a golden and a silver age. He portrays a sequence of

metallic ages, but it is a degradation rather than a progression. Each

age has less of a moral value than the preceding. Of his own age he says: "And I wish that I were not any part of the fifth generation of men, but had died before it came, or had been born afterward."

The Progress of Lucretius

The moral metaphor of the ages of metals continued. Lucretius, however, replaced moral degradation with the concept of progress, which he conceived to be like the growth of an individual human being. The concept is evolutionary:

For the nature of the world as a whole is altered by age. Everything must pass through successive phases. Nothing remains forever what it was. Everything is on the move. Everything is transformed by nature and forced into new paths ... The Earth passes through successive phases, so that it can no longer bear what it could, and it can now what it could not before.

Page 1 Chapter 1 of De Rerum Natura, 1675, dedicating the poem to Alma Venus

The Romans believed that the species of animals, including humans,

were spontaneously generated from the materials of the Earth, because of

which the Latin word mater, "mother", descends to

English-speakers as matter and material. In Lucretius the Earth is a

mother, Venus, to whom the poem is dedicated in the first few lines. She

brought forth humankind by spontaneous generation. Having been given

birth as a species, humans must grow to maturity by analogy with the

individual. The different phases of their collective life are marked by

the accumulation of customs to form material civilization:

The earliest weapons were hands, nails and teeth. Next came stones and branches wrenched from trees, and fire and flame as soon as these were discovered. Then men learnt to use tough iron and copper. With copper they tilled the soil. With copper they whipped up the clashing waves of war, ... Then by slow degrees the iron sword came to the fore; the bronze sickle fell into disrepute; the ploughman began to cleave the earth with iron, ...

Lucretius envisioned a pre-technological human that was "far tougher

than the men of today ... They lived out their lives in the fashion of

wild beasts roaming at large."

The next stage was the use of huts, fire, clothing, language and the

family. City-states, kings and citadels followed them. Lucretius

supposes that the initial smelting of metal occurred accidentally in

forest fires. The use of copper followed the use of stones and branches

and preceded the use of iron.

Early lithic analysis by Michele Mercati

Michele Mercati, Commemorative Medal.

By the 16th century, a tradition had developed based on observational

incidents, true or false, that the black objects found widely scattered

in large quantities over Europe had fallen from the sky during

thunderstorms and were therefore to be considered generated by

lightning. They were so published by Konrad Gessner in De rerum fossilium, lapidum et gemmarum maxime figuris & similitudinibus at Zurich in 1565 and by many others less famous. The name ceraunia, "thunderstones," had been assigned.

Ceraunia were collected by many persons over the centuries including Michele Mercati,

Superintendent of the Vatican Botanical Garden in the late 16th

century. He brought his collection of fossils and stones to the Vatican,

where he studied them at leisure, compiling the results in a

manuscript, which was published posthumously by the Vatican at Rome in

1717 as Metallotheca. Mercati was interested in Ceraunia cuneata,

"wedge-shaped thunderstones," which seemed to him to be most like axes

and arrowheads, which he now called ceraunia vulgaris, "folk

thunderstones," distinguishing his view from the popular one. His view was based on what may be the first in-depth lithic analysis

of the objects in his collection, which led him to believe that they

are artifacts and to suggest that the historical evolution of these

artifacts followed a scheme.

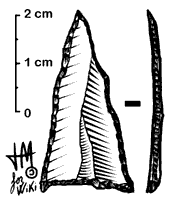

Mercati examining the surfaces of the ceraunia noted that the

stones were of flint and that they had been chipped all over by another

stone to achieve by percussion their current forms. The protrusion at

the bottom he identified as the attachment point of a haft. Concluding

that these objects were not ceraunia he compared collections to

determine exactly what they were. Vatican collections included artifacts

from the New World of exactly the shapes of the supposed ceraunia. The

reports of the explorers had identified them to be implements and

weapons or parts of them.

Mercati posed the question to himself, why would anyone prefer to

manufacture artifacts of stone rather than of metal, a superior

material?

His answer was that metallurgy was unknown at that time. He cited

Biblical passages to prove that in Biblical times stone was the first

material used. He also revived the 3-age system of Lucretius, which

described a succession of periods based on the use of stone (and wood),

bronze and iron respectively. Due to lateness of publication, Mercati's

ideas were already being developed independently; however, his writing

served as a further stimulus.

The usages of Mahudel and de Jussieu

On 12 November 1734, Nicholas Mahudel, physician, antiquarian and numismatist, read a paper at a public sitting of the Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

in which he defined three "usages" of stone, bronze and iron in a

chronological sequence. He had presented the paper several times that

year but it was rejected until the November revision was finally

accepted and published by the Academy in 1740. It was entitled Les Monumens les plus anciens de l'industrie des hommes, et des Arts reconnus dans les Pierres de Foudres. It expanded the concepts of Antoine de Jussieu, who had gotten a paper accepted in 1723 entitled De l'Origine et des usages de la Pierre de Foudre. In Mahudel, there is not just one usage for stone, but two more, one each for bronze and iron.

He begins his treatise with descriptions and classifications of the Pierres de Tonnerre et de Foudre,

the ceraunia of contemporaneous European interest. After cautioning the

audience that natural and man-made objects are often easily confused,

he asserts that the specific "figures" or "formes that can be distinguished (formes qui les font distingues)" of the stones were man-made, not natural:

It was Man's hand that made them serve as instruments (C'est la main des hommes qui les leur a données pour servir d'instrumens...)

Their cause, he asserts, is "the industry of our forefathers (l'industrie de nos premiers pères)."

He adds later that bronze and iron implements imitate the uses of the

stone ones, suggesting a replacement of stone with metals. Mahudel is

careful not to take credit for the idea of a succession of usages in

time but states: "it is Michel Mercatus, physician of Clement VIII who

first had this idea". He does not coin a term for ages, but speaks only of the times of usages. His use of l'industrie

foreshadows the 20th century "industries," but where the moderns mean

specific tool traditions, Mahudel meant only the art of working stone

and metal in general.

The three-age system of C. J. Thomsen

Thomsen

explaining the Three-age System to visitors at the Museum of Northern

Antiquities, then at the Christiansborg Palace, in Copenhagen, 1846.

Drawing by Magnus Petersen, Thomsen's illustrator.

An important step in the development of the Three-age System came when the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

was able to use the Danish national collection of antiquities and the

records of their finds as well as reports from contemporaneous

excavations to provide a solid empirical basis for the system. He showed

that artifacts could be classified into types and that these types

varied over time in ways that correlated with the predominance of stone,

bronze or iron implements and weapons. In this way he turned the

Three-age System from being an evolutionary scheme based on intuition

and general knowledge into a system of relative chronology

supported by archaeological evidence. Initially, the three-age system

as it was developed by Thomsen and his contemporaries in Scandinavia,

such as Sven Nilsson and J.J.A. Worsaae,

was grafted onto the traditional biblical chronology. But, during the

1830s they achieved independence from textual chronologies and relied

mainly on typology and stratigraphy.

In 1816 Thomsen at age 27 was appointed to succeed the retiring Rasmus Nyerup as Secretary of the Kongelige Commission for Oldsagers Opbevaring ("Royal Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities"), which had been founded in 1807.

The post was unsalaried; Thomsen had independent means. At his

appointment Bishop Münter said that he was an "amateur with a great

range of accomplishments." Between 1816 and 1819 he reorganized the

commission's collection of antiquities. In 1819 he opened the first

Museum of Northern Antiquities, in Copenhagen, in a former monastery, to

house the collections. It later became the National Museum.

Like the other antiquarians Thomsen undoubtedly knew of the three-age model of prehistory through the works of Lucretius, the Dane Vedel Simonsen, Montfaucon and Mahudel. Sorting the material in the collection chronologically

he mapped out which kinds of artifacts co-occurred in deposits and

which did not, as this arrangement would allow him to discern any trends

that were exclusive to certain periods. In this way he discovered that

stone tools did not co-occur with bronze or iron in the earliest

deposits while subsequently bronze did not co-occur with iron - so that

three periods could be defined by their available materials, stone,

bronze and iron.

To Thomsen the find circumstances were the key to dating. In 1821 he wrote in a letter to fellow prehistorian Schröder:

nothing is more important than to point out that hitherto we have not paid enough attention to what was found together.

and in 1822:

we still do not know enough about most of the antiquities either; ... only future archaeologists may be able to decide, but they will never be able to do so if they do not observe what things are found together and our collections are not brought to a greater degree of perfection.

This analysis emphasizing co-occurrence and systematic attention to

archaeological context allowed Thomsen to build a chronological

framework of the materials in the collection and to classify new finds

in relation to the established chronology, even without much knowledge

of their provenience. In this way, Thomsen's system was a true

chronological system rather than an evolutionary or technological

system.

Exactly when his chronology was reasonably well established is not

clear, but by 1825 visitors to the museum were being instructed in his

methods. In that year also he wrote to J.G.G. Büsching:

To put artifacts in their proper context I consider it most important to pay attention to the chronological sequence, and I believe that the old idea of first stone, then copper, and finally iron, appears to be ever more firmly established as far as Scandinavia is concerned.

By 1831 Thomsen was so certain of the utility of his methods that he circulated a pamphlet, "Scandinavian Artifacts and Their Preservation,

advising archaeologists to "observe the greatest care" to note the

context of each artifact. The pamphlet had an immediate effect. Results

reported to him confirmed the universality of the Three-age System.

Thomsen also published in 1832 and 1833 articles in the Nordisk Tidsskrift for Oldkyndighed, "Scandinavian Journal of Archaeology."

He already had an international reputation when in 1836 the Royal

Society of Northern Antiquaries published his illustrated contribution

to "Guide to Scandinavian Archaeology" in which he put forth his

chronology together with comments about typology and stratigraphy.

Reconstructed Iron Age home in Spain

Thomsen was the first to perceive typologies of grave goods, grave

types, methods of burial, pottery and decorative motifs, and to assign

these types to layers found in excavation. His published and personal

advice to Danish archaeologists concerning the best methods of

excavation produced immediate results that not only verified his system

empirically but placed Denmark in the forefront of European archaeology

for at least a generation. He became a national authority when C.C Rafn, secretary of the Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab ("Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries"), published his principal manuscript in Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed ("Guide to Scandinavian Archaeology")

in 1836. The system has since been expanded by further subdivision of

each era, and refined through further archaeological and anthropological

finds.

Stone Age subdivisions

The savagery and civilization of Sir John Lubbock

It

was to be a full generation before British archaeology caught up with

the Danish. When it did, the leading figure was another multi-talented

man of independent means: John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury. After reviewing the Three-age System from Lucretius to Thomsen, Lubbock improved it and took it to another level, that of cultural anthropology.

Thomsen had been concerned with techniques of archaeological

classification. Lubbock found correlations with the customs of savages

and civilization.

In his 1865 book, Prehistoric Times, Lubbock divided the Stone Age in Europe, and possibly nearer Asia and Africa, into the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic:

- "That of the Drift... This we may call the 'Palaeolithic' Period."

- "The later, or polished Stone Age ... in which, however, we find no trace ... of any metal, excepting gold, ... This we may call the 'Neolithic' Period."

- "The Bronze Age, in which bronze was used for arms and cutting instruments of all kinds."

- "The Iron Age, in which that metal had superseded bronze."

By "drift" Lubbock meant river-drift, the alluvium deposited by a

river. For the interpretation of Palaeolithic artifacts, Lubbock,

pointing out that the times are beyond the reach of history and

tradition, suggests an analogy, which was adopted by the

anthropologists. Just as the paleontologist uses modern elephants to

help reconstruct fossil pachyderms, so the archaeologist is justified in

using the customs of the "non-metallic savages" of today to understand

"the early races which inhabited our continent."

He devotes three chapters to this approach, covering the "modern

savages" of the Indian and Pacific Oceans and the Western Hemisphere,

but something of a deficit in what would be called today his correct

professionalism reveals a field yet in its infancy:

Perhaps it will be thought ... I have selected ... the passages most unfavorable to savages. ... In reality the very reverse in the case. ... Their real condition is even worse and more abject than that which I have endeavoured to depict.

The elusive Mesolithic of Hodder Westropp

Bone harpoon studded with microliths, a Mode 5 composite hunting implement.

Sir John Lubbock's use of the terms Palaeolithic ("Old Stone Age")

and Neolithic ("New Stone Age") were immediately popular. They were

applied, however, in two different senses: geologic and anthropologic.

In 1867-1868 Ernst Haeckel in 20 public lectures in Jena, entitled General Morphology,

to be published in 1870, referred to the Archaeolithic, the

Palaeolithic, the Mesolithic and the Caenolithic as periods in geologic

history.

He could only have got these terms from Hodder Westropp, who took

Palaeolithic from Lubbock, invented Mesolithic ("Middle Stone Age") and

Caenolithic instead of Lubbock's Neolithic. None of these terms appear

anywhere, including the writings of Haeckel, before 1865. Haeckel's use

was innovative.

Westropp first used Mesolithic and Caenolithic in 1865, almost

immediately after the publication of Lubbock's first edition. He read a

paper on the topic before the Anthropological Society of London in 1865, published in 1866 in the Memoirs. After asserting:

Man, in all ages and in all stages of his development, is a tool-making animal.

Westropp goes on to define "different epochs of flint, stone, bronze

or iron; ..." He never did distinguish the flint from the stone age

(having realized they were one and the same), but he divided the Stone

Age as follows:

- "The flint implements of the gravel-drift"

- "The flint implements found in Ireland and Denmark"

- "Polished stone implements"

These three ages were named respectively the Palaeolithic, the

Mesolithic and the Kainolithic. He was careful to qualify these by

stating:

Their presence is thus not always an evidence of a high antiquity, but of an early and barbarous state; ...

Lubbock's savagery was now Westropp's barbarism. A fuller exposition of the Mesolithic waited for his book, Pre-Historic Phases,

dedicated to Sir John Lubbock, published in 1872. At that time he

restored Lubbock's Neolithic and defined a Stone Age divided into three

phases and five stages.

The First Stage, "Implements of the Gravel Drift," contains implements that were "roughly knocked into shape." His illustrations show Mode 1 and Mode 2 stone tools, basically Acheulean handaxes. Today they are in the Lower Palaeolithic.

The Second Stage, "Flint Flakes" are of the "simplest form" and were struck off cores.

Westropp differs in this definition from the modern, as Mode 2 contains

flakes for scrapers and similar tools. His illustrations, however, show

Modes 3 and 4, of the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. His extensive

lithic analysis leaves no doubt. They are, however, part of Westropp's

Mesolithic.

The Third Stage, "a more advanced stage" in which "flint flakes

were carefully chipped into shape," produced small arrowheads from

shattering a piece of flint into "a hundred pieces", selecting the most

suitable and working it with a punch.

The illustrations show that he had microliths, or Mode 5 tools in mind.

His Mesolithic is therefore partly the same as the modern.

The Fourth Stage is a part of the Neolithic that is transitional

to the Fifth Stage: axes with ground edges leading to implements totally

ground and polished. Westropp's agriculture is removed to the Bronze

Age, while his Neolithic is pastoral. The Mesolithic is reserved to

hunters.

Piette finds the Mesolithic

Mas-d'Azil Grotto

In that same year, 1872, Sir John Evans produced a massive work, The Ancient Stone Implements, in which he in effect repudiated the Mesolithic, making a point to ignore it, denying it by name in later editions. He wrote:

Sir John Lubbock has proposed to call them the Archaeolithic, or Palaeolithic, and the Neolithic Periods respectively, terms which have met with almost general acceptance, and of which I shall avail myself in the course of this work.

Evans did not, however, follow Lubbock's general trend, which was

typological classification. He chose instead to use type of find site as

the main criterion, following Lubbock's descriptive terms, such as

tools of the drift. Lubbock had identified drift sites as containing

Palaeolithic material. Evans added to them the cave sites. Opposed to

drift and cave were the surface sites, where chipped and ground tools

often occurred in unlayered contexts. Evans decided he had no choice but

to assign them all to the most recent. He therefore consigned them to

the Neolithic and used the term "Surface Period" for it.

Having read Westropp, Sir John knew perfectly well that all the

former's Mesolithic implements were surface finds. He used his prestige

to quell the concept of Mesolithic as best he could, but the public

could see that his methods were not typological. The less prestigious

scientists publishing in the smaller journals continued to look for a

Mesolithic. For example, Isaac Taylor in The Origin of the Aryans,

1889, mentions the Mesolithic but briefly, asserting, however, that it

formed "a transition between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Periods." Nevertheless, Sir John fought on, opposing the Mesolithic by name as late as the 1897 edition of his work.

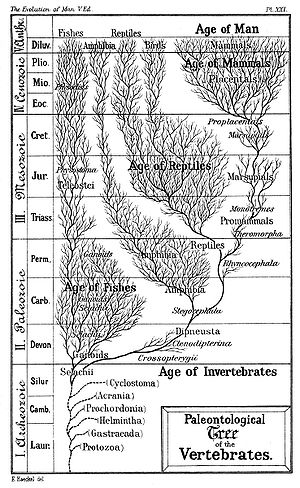

Meanwhile, Haeckel had totally abandoned the geologic uses of the

-lithic terms. The concepts of Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic had

originated in the early 19th century and were gradually becoming coin of

the geologic realm. Realizing he was out of step, Haeckel started to

transition to the -zoic system as early as 1876 in The History of Creation, placing the -zoic form in parentheses next to the -lithic form.

The gauntlet was officially thrown down before Sir John by J. Allen Brown, speaking for the opposition before the Anthropological Institute on 8 March 1892. In the journal he opens the attack by striking at a "hiatus" in the record:

It has been generally assumed that a break occurred between the period during which ... the continent of Europe was inhabited by Palaeolithic Man and his Neolithic successor ... No physical cause, no adequate reasons have ever been assigned for such a hiatus in human existence ...

The main hiatus at that time was between British and French

archaeology, as the latter had already discovered the gap 20 years

earlier and had already considered three answers and arrived at one

solution, the modern. Whether Brown did not know or was pretending not

to know is unclear. In 1872, the very year of Evans' publication, Mortillet had presented the gap to the Congrès international d'Anthropologie at Brussels:

Between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic, there is a wide and deep gap, a large hiatus.

Apparently prehistoric man was hunting big game with stone tools one

year and farming with domestic animals and ground stone tools the next.

Mortillet postulated a "time then unknown (époque alors inconnue)" to fill the gap. The hunt for the "unknown" was on. On 16 April 1874, Mortillet retracted. "That hiatus is not real (Cet hiatus n'est pas réel)," he said before the Société d'Anthropologie,

asserting that it was an informational gap only. The other theory had

been a gap in nature, that, because of the ice age, man had retreated

from Europe. The information must now be found. In 1895 Édouard Piette stated that he had heard Édouard Lartet speak of "the remains from the intermediate period (les vestiges de l'époque intermédiaire)", which were yet to be discovered, but Lartet had not published this view. The gap had become a transition. However, asserted Piette:

I was fortunate to discover the remains of that unknown time which separated the Magdalenian age from that of polished stone axes ... it was, at Mas-d'Azil in 1887 and 1888 when I made this discovery.

He had excavated the type site of the Azilian

Culture, the basis of today's Mesolithic. He found it sandwiched

between the Magdalenian and the Neolithic. The tools were like those of

the Danish kitchen-middens, termed the Surface Period by Evans, which were the basis of Westropp's Mesolithic. They were Mode 5 stone tools, or microliths. He mentions neither Westropp nor the Mesolithic, however. For him this was a "solution of continuity (solution de continuité)" To it he assigns the semi-domestication of dog, horse, cow, etc., which "greatly facilitated the work of neolithic man (a beaucoup facilité la tàche de l'homme néolithique)."

Brown in 1892 does not mention Mas-d'Azil. He refers to the "transition

or 'Mesolithic' forms" but to him these are "rough hewn axes chipped

over the entire surface" mentioned by Evans as the earliest of the

Neolithic. Where Piette believed he had discovered something new, Brown wanted to break out known tools considered Neolithic.

The Epipaleolithic and Protoneolithic of Stjerna and Obermaier

Small Magdalenian carving representing a horse.

Sir John Evans never changed his mind, giving rise to a dichotomous

view of the Mesolithic and a multiplication of confusing terms. On the

continent, all seemed settled: there was a distinct Mesolithic with its

own tools and both tools and customs were transitional to the Neolithic.

Then in 1910, the Swedish archaeologist, Knut Stjerna,

addressed another problem of the Three-Age System: although a culture

was predominantly classified as one period, it might contain material

that was the same as or like that of another. His example was the Gallery grave

Period of Scandinavia. It was not uniformly Neolithic, but contained

some objects of bronze and more importantly to him three different

subcultures.

One of these "civilisations" (sub-cultures) located in the north and east of Scandinavia

was rather different, featuring but few gallery graves, using instead

stone-lined pit graves containing implements of bone, such as harpoon

and javelin heads. He observed that they "persisted during the recent

Paleolithic period and also during the Protoneolithic." Here he had used

a new term, "Protoneolithic", which was according to him to be applied

to the Danish kitchen-middens.

Stjerna also said that the eastern culture "is attached to the Paleolithic civilization (se trouve rattachée à la civilisation paléolithique)." However, it was not intermediary and of its intermediates he said "we cannot discuss them here (nous ne pouvons pas examiner ici)." This "attached" and non-transitional culture he chose to call the Epipaleolithic, defining it as follows:

With Epipaleolithic I mean the period during the early days that followed the age of the reindeer, the one that retained Paleolithic customs. This period has two stages in Scandinavia, that of Maglemose and that of Kunda. (Par époque épipaléolithique j'entends la période qui, pendant les premiers temps qui ont suivi l'âge du Renne, conserve les coutumes paléolithiques. Cette période présente deux étapes en Scandinavie, celle de Maglemose et de Kunda.)

Tardenoisian Mode 5-point—Mesolithic or Epipaleolithic?

There is no mention of any Mesolithic, but the material he described

had been previously connected with the Mesolithic. Whether or not

Stjerna intended his Protoneolithic and Epipaleolithic as a replacement

for the Mesolithic is not clear, but Hugo Obermaier,

a German archaeologist who taught and worked for many years in Spain,

to whom the concepts are often erroneously attributed, used them to

mount an attack on the entire concept of Mesolithic. He presented his

views in El Hombre fósil, 1916, which was translated into English

in 1924. Viewing the Epipaleolithic and the Protoneolithic as a

"transition" and an "interim" he affirmed that they were not any sort of

"transformation:"

But in my opinion this term is not justified, as it would be if these phases presented a natural evolutionary development – a progressive transformation from Paleolithic to Neolithic. In reality, the final phase of the Capsian, the Tardenoisian, the Azilian and the northern Maglemose industries are the posthumous descendants of the Palaeolithic ...

The ideas of Stjerna and Obermaier introduced a certain ambiguity

into the terminology, which subsequent archaeologists found and find

confusing. Epipaleolithic and Protoneolithic cover the same cultures,

more or less, as does the Mesolithic. Publications on the Stone Age

after 1916 include some sort of explanation of this ambiguity, leaving

room for different views. Strictly speaking the Epipaleolithic is the

earlier part of the Mesolithic. Some identify it with the Mesolithic. To

others it is an Upper Paleolithic transition to the Mesolithic. The

exact use in any context depends on the archaeological tradition or the

judgement of individual archaeologists. The issue continues.

Lower, middle and upper from Haeckel to Sollas

Haeckel's tree growing through the layers. In geology, the tripartite division did not stand the test of time.

The post-Darwinian

approach to the naming of periods in earth history focused at first on

the lapse of time: early (Palaeo-), middle (Meso-) and late (Ceno-).

This conceptualization automatically imposes a three-age subdivision to

any period, which is predominant in modern archaeology: Early, Middle

and Late Bronze Age; Early, Middle and Late Minoan, etc. The criterion

is whether the objects in question look simple or are elaborative. If a

horizon contains objects that are post-late and simpler-than-late they

are sub-, as in Submycenaean.

Haeckel's presentations are from a different point of view. His History of Creation

of 1870 presents the ages as "Strata of the Earth's Crust," in which he

prefers "upper", "mid-" and "lower" based on the order in which one

encounters the layers. His analysis features an Upper and Lower Pliocene

as well as an Upper and Lower Diluvial (his term for the Pleistocene). Haeckel, however, was relying heavily on Lyell. In the 1833 edition of Principles of Geology (the first) Lyell devised the terms Eocene, Miocene and Pliocene to mean periods of which the "strata" contained some (Eo-, "early"), lesser (Mio-) and greater (Plio-) numbers of "living Mollusca represented among fossil assemblages of western Europe."

The Eocene was given Lower, Middle, Upper; the Miocene a Lower and

Upper; and the Pliocene an Older and Newer, which scheme would indicate

an equivalence between Lower and Older, and Upper and Newer.

In a French version, Nouveaux Éléments de Géologie, in 1839 Lyell called the Older Pliocene the Pliocene and the Newer Pliocene the Pleistocene (Pleist-, "most"). Then in Antiquity of Man in 1863 he reverted to his previous scheme, adding "Post-Tertiary" and "Post-Pliocene." In 1873 the Fourth Edition of Antiquity of Man

restores Pleistocene and identifies it with Post-Pliocene. As this work

was posthumous, no more was heard from Lyell. Living or deceased, his

work was immensely popular among scientists and laymen alike.

"Pleistocene" caught on immediately; it is entirely possible that he

restored it by popular demand. In 1880 Dawkins published The Three Pleistocene Strata containing a new manifesto for British archaeology:

The continuity between geology, prehistoric archaeology and history is so direct that it is impossible to picture early man in this country without using the results of all these three sciences.

He intends to use archaeology and geology to "draw aside the veil"

covering the situations of the peoples mentioned in proto-historic

documents, such as Caesar's Commentaries and the Agricola of Tacitus. Adopting Lyell's scheme of the Tertiary, he divides Pleistocene into Early, Mid- and Late. Only the Palaeolithic falls into the Pleistocene; the Neolithic is in the "Prehistoric Period" subsequent.

Dawkins defines what was to become the Upper, Middle and Lower

Paleolithic, except that he calls them the "Upper Cave-Earth and

Breccia," the "Middle Cave-Earth," and the "Lower Red Sand," with reference to the names of the layers. The next year, 1881, Geikie solidified the terminology into Upper and Lower Palaeolithic:

In Kent's Cave the implements obtained from the lower stages were of a much ruder description than the various objects detected in the upper cave-earth ... And a very long time must have elapsed between the formation of the lower and upper Palaeolithic beds in that cave.

The Middle Paleolithic in the modern sense made its appearance in 1911 in the 1st edition of William Johnson Sollas' Ancient Hunters. It had been used in varying senses before then. Sollas associates the period with the Mousterian technology and the relevant modern people with the Tasmanians.

In the 2nd edition of 1915 he has changed his mind for reasons that are

not clear. The Mousterian has been moved to the Lower Paleolithic and

the people changed to the Australian aborigines; furthermore, the association has been made with Neanderthals and the Levalloisian

added. Sollas says wistfully that they are in "the very middle of the

Palaeolithic epoch." Whatever his reasons, the public would have none of

it. From 1911 on, Mousterian was Middle Paleolithic, except for

holdouts. Alfred L. Kroeber in 1920, Three essays on the antiquity and races of man, reverting to Lower Paleolithic, explains that he is following Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet. The English-speaking public remained with Middle Paleolithic.

Early and late from Worsaae through the three-stage African system

Thomsen

had formalized the Three-age System by the time of its publication in

1836. The next step forward was the formalization of the Palaeolithic

and Neolithic by Sir John Lubbock in 1865. Between these two times

Denmark held the lead in archaeology, especially because of the work of

Thomsen's at first junior associate and then successor, Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, rising in the last year of his life to Kultus Minister of Denmark. Lubbock offers full tribute and credit to him in Prehistoric Times.

Worsaae in 1862 in Om Tvedelingen af Steenalderen, previewed in English even before its publication by The Gentleman's Magazine, concerned about changes in typology during each period, proposed a bipartite division of each age:

Both for Bronze and Stone it was now evident that a few hundred years would not suffice. In fact, good grounds existed for dividing each of these periods into two, if not more.

He called them earlier or later. The three ages became six periods.

The British seized on the concept immediately. Worsaae's earlier and

later became Lubbock's palaeo- and neo- in 1865, but alternatively

English speakers used Earlier and Later Stone Age, as did Lyell's 1883

edition of Principles of Geology, with older and younger as

synonyms. As there is no room for a middle between the comparative

adjectives, they were later modified to early and late. The scheme

created a problem for further bipartite subdivisions, which would have

resulted in such terms as early early stone age, but that terminology

was avoided by adoption of Geikie's upper and lower Paleolithic.

Amongst African archaeologists, the terms Old Stone Age, Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age are preferred.

Wallace's grand revolution recycled

When Sir John Lubbock was doing the preliminary work for his 1865 magnum opus, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were jointly publishing their first papers On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. Darwins's On the Origin of Species came out in 1859, but he did not elucidate the theory of evolution as it applies to man until the Descent of Man in 1871. Meanwhile, Wallace read a paper in 1864 to the Anthropological Society of London that was a major influence on Sir John, publishing in the very next year. He quoted Wallace:

From the moment when the first skin was used as a covering, when the first rude spear was formed to assist in the chase, the first seed sown or shoot planted, a grand revolution was effected in nature, a revolution which in all the previous ages of the world's history had had no parallel, for a being had arisen who was no longer necessarily subject to change with the changing universe,—a being who was in some degree superior to nature, inasmuch as he knew how to control and regulate her action, and could keep himself in harmony with her, not by a change in body, but by an advance in mind.

Wallace distinguishing between mind and body was asserting that natural selection

shaped the form of man only until the appearance of mind; after then,

it played no part. Mind formed modern man, meaning that result of mind,

culture. Its appearance overthrew the laws of nature. Wallace used the

term "grand revolution." Although Lubbock believed that Wallace had gone

too far in that direction he did adopt a theory of evolution combined

with the revolution of culture. Neither Wallace not Lubbock offered any

explanation of how the revolution came about, or felt that they had to

offer one. Revolution is an acceptance that in the continuous evolution

of objects and events sharp and inexplicable disconformities do occur,

as in geology. And so it is not surprising that in the 1874 Stockholm meeting of the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology, in response to Ernst Hamy's denial of any "break" between Paleolithic and Neolithic based on material from dolmens

near Paris "showing a continuity between the paleolithic and neolithic

folks," Edouard Desor, geologist and archaeologist, replied: "that the introduction of domesticated animals was a complete revolution and enables us to separate the two epochs completely."

A revolution as defined by Wallace and adopted by Lubbock is a change of

regime, or rules. If man was the new rule-setter through culture then

the initiation of each of Lubbock's four periods might be regarded as a

change of rules and therefore as a distinct revolution, and so Chambers's Journal, a reference work, in 1879 portrayed each of them as:

...an advance in knowledge and civilization which amounted to a revolution in the then existing manners and customs of the world.

Because of the controversy over Westropp's Mesolithic and Mortillet's

Gap beginning in 1872 archaeological attention focused mainly on the

revolution at the Palaeolithic—Neolithic boundary as an explanation of

the gap. For a few decades the Neolithic Period, as it was called, was

described as a kind of revolution. In the 1890s, a standard term, the

Neolithic Revolution, began to appear in encyclopedias such as Pears. In

1925 the Cambridge Ancient History reported:

There are quite a large number of archaeologists who justifiably consider the period of the Late Stone Age to be a neolithic revolution and an economic revolution at the same time. For that is the period when primitive agriculture developed and cattle breeding began.

Vere Gordon Childe's revolution for the masses

In 1936 a champion came forward who would advance the Neolithic Revolution into the mainstream view: Vere Gordon Childe. After giving the Neolithic Revolution scant mention in his first notable work, the 1928 edition of New Light on the Most Ancient East, Childe made a major presentation in the first edition of Man Makes Himself

in 1936 developing Wallace's and Lubbock's theme of the human

revolution against the supremacy of nature and supplying detail on two

revolutions, the Paleolithic—Neolithic and the Neolithic-Bronze Age,

which he called the Second or Urban revolution.

Lubbock had been as much of an ethnologist as an archaeologist. The founders of cultural anthropology, such as Tylor and Morgan,

were to follow his lead on that. Lubbock created such concepts as

savages and barbarians based on the customs of then modern tribesmen and

made the presumption that the terms can be applied without serious

inaccuracy to the men of the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. Childe broke

with this view:

The assumption that any savage tribe today is primitive, in the sense that its culture faithfully reflects that of much more ancient men is gratuitous.

Childe concentrated on the inferences to be made from the artifacts:

But when the tools ... are considered ... in their totality, they may reveal much more. They disclose not only the level of technical skill ... but also their economy .... The archaeologists's ages correspond roughly to economic stages. Each new "age" is ushered in by an economic revolution ....

The archaeological periods were indications of economic ones:

Archaeologists can define a period when it was apparently the sole economy, the sole organization of production ruling anywhere on the earth's surface.

These periods could be used to supplement historical ones where

history was not available. He reaffirmed Lubbock's view that the

Paleolithic was an age of food gathering and the Neolithic an age of

food production. He took a stand on the question of the Mesolithic

identifying it with the Epipaleolithic. The Mesolithic was to him "a

mere continuance of the Old Stone Age mode of life" between the end of

the Pleistocene and the start of the Neolithic. Lubbock's terms "savagery" and "barbarism" do not much appear in Man Makes Himself but the sequel, What Happened in History

(1942), reuses them (attributing them to Morgan, who got them from

Lubbock) with an economic significance: savagery for food-gathering and

barbarism for Neolithic food production. Civilization begins with the

urban revolution of the Bronze Age.

The Pre-pottery Neolithic of Garstang and Kenyon at Jericho

Even

as Childe was developing this revolution theme the ground was sinking

under him. Lubbock did not find any pottery associated with the

Paleolithic, asserting of its to him last period, the Reindeer, "no

fragments of metal or pottery have yet been found." He did not generalize but others did not hesitate to do so. The next year, 1866, Dawkins proclaimed of Neolithic people that "these invented the use of pottery...." From then until the 1930s pottery was considered a sine qua non of the Neolithic. The term Pre-Pottery Age came into use in the late 19th century but it meant Paleolithic.

Meanwhile, the Palestine Exploration Fund

founded in 1865 completing its survey of excavatable sites in Palestine

in 1880 began excavating in 1890 at the site of ancient Lachish near Jerusalem, the first of a series planned under the licensing system of the Ottoman Empire. Under their auspices in 1908 Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger began excavation at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) previously excavated for the first time by Sir Charles Warren

in 1868. They discovered a Neolithic and Bronze Age city there.

Subsequent excavations in the region by them and others turned up other

walled cities that appear to have preceded the Bronze Age urbanization.

All excavation ceased for World War I. When it was over the Ottoman Empire was no longer a factor there. In 1919 the new British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem assumed archaeological operations in Palestine. John Garstang

finally resumed excavation at Jericho 1930-1936. The renewed dig

uncovered another 3000 years of prehistory that was in the Neolithic but

did not make use of pottery. He called it the Pre-pottery Neolithic, as opposed to the Pottery Neolithic, subsequently often called the Aceramic or Pre-ceramic and Ceramic Neolithic.

Kathleen Kenyon

was a young photographer then with a natural talent for archaeology.

Solving a number of dating problems she soon advanced to the forefront

of British archaeology through skill and judgement. In World War II she served as a commander in the Red Cross.

In 1952–58 she took over operations at Jericho as the Director of the

British School, verifying and expanding Garstang's work and conclusions.

There were two Pre-pottery Neolithic periods, she concluded, A and B.

Moreover, the PPN had been discovered at most of the major Neolithic

sites in the near East and Greece. By this time her personal stature in

archaeology was at least equal to that of V. Gordon Childe. While the

three-age system was being attributed to Childe in popular fame, Kenyon

became gratuitously the discoverer of the PPN. More significantly the

question of revolution or evolution of the Neolithic was increasingly

being brought before the professional archaeologists.

Bronze Age subdivisions

Danish

archaeology took the lead in defining the Bronze Age, with little of

the controversy surrounding the Stone Age. British archaeologists

patterned their own excavations after those of the Danish, which they

followed avidly in the media. References to the Bronze Age in British

excavation reports began in the 1820s contemporaneously with the new

system being promulgated by C.J. Thomsen. Mention of the Early and Late

Bronze Age began in the 1860s following the bipartite definitions of

Worsaae.

The tripartite system of Sir John Evans

In 1874 at the Stockholm meeting of the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology,

a suggestion was made by A. Bertrand that no distinct age of bronze had

existed, that the bronze artifacts discovered were really part of the

Iron Age. Hans Hildebrand in refutation pointed to two Bronze Ages and a transitional period in Scandinavia. John Evans

denied any defect of continuity between the two and asserted there were

three Bronze Ages, "the early, middle and late bronze age."

His view for the Stone Age, following Lubbock, was quite different, denying, in The Ancient Stone Implements, any concept of a Middle Stone Age. In his 1881 parallel work, The Ancient Bronze Implements,

he affirmed and further defined the three periods, strangely enough

recusing himself from his previous terminology, Early, Middle and Late

Bronze Age (the current forms) in favor of "an earlier and later stage" and "middle".

He uses Bronze Age, Bronze Period, Bronze-using Period and Bronze

Civilization interchangeably. Apparently Evans was sensitive of what had

gone before, retaining the terminology of the bipartite system while

proposing a tripartite one. After stating a catalogue of types of bronze

implements he defines his system:

The Bronze Age of Britain may, therefore, be regarded as an aggregate of three stages: the first, that characterized by the flat or slightly flanged celts, and the knife-daggers ... the second, that characterized by the more heavy dagger-blades and the flanged celts and tanged spear-heads or daggers, ... and the third, by palstaves and socketed celts and the many forms of tools and weapons, ... It is in this third stage that the bronze sword and the true socketed spear-head first make their advent.

From Evans' gratuitous Copper Age to the mythical chalcolithic

In chapter 1 of his work, Evans proposes for the first time a transitional Copper Age between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age.

He adduces evidence from far-flung places such as China and the

Americas to show that the smelting of copper universally preceded

alloying with tin

to make bronze. He does not know how to classify this fourth age. On

the one hand he distinguishes it from the Bronze Age. On the other hand,

he includes it:

In thus speaking of a bronze-using period I by no means wish to exclude the possible use of copper unalloyed with tin.

Evans goes into considerable detail tracing references to the metals in classical literature: Latin aer, aeris and Greek chalkós first for "copper" and then for "bronze." He does not mention the adjective of aes, which is aēneus,

nor is he interested in formulating New Latin words for the Copper Age,

which is good enough for him and many English authors from then on. He

offers literary proof that bronze had been in use before iron and copper

before bronze.

In 1884 the center of archaeological interest shifted to Italy with the excavation of Remedello and the discovery of the Remedello culture by Gaetano Chierici. According to his 1886 biographers, Luigi Pigorini

and Pellegrino Strobel, Chierici devised the term Età Eneo-litica to

describe the archaeological context of his findings, which he believed

were the remains of Pelasgians, or people that preceded Greek and Latin speakers in the Mediterranean. The age (Età) was:

A period of transition from the age of stone to that of bronze (periodo di transizione dall'età della pietra a quella del bronzo)

Whether intentional or not, the definition was the same as Evans',

except that Chierici was adding a term to New Latin. He describes the

transition by stating the beginning (litica, or stone age) and the

ending (eneo-, or Bronze Age); in English, "the stone-to-bronze period."

Shortly after, "Eneolithic" or "Aeneolithic" began turning up in

scholarly English as a synonym for "Copper Age." Sir John's own son, Arthur Evans,

beginning to come into his own as an archaeologist and already studying

Cretan civilization, refers in 1895 to some clay figures of

"aeneolithic date" (quotes his).

End of the Iron Age

The

three-age system is a way of dividing prehistory, and the Iron Age is

therefore considered to end in a particular culture with either the

start of its protohistory, when it begins to be written about by outsiders, or when its own historiography

begins. Although iron is still the major hard material in use in

modern civilization, and steel is a vital and indispensable modern

industry, as far as archaeologists are concerned the Iron Age has

therefore now ended for all cultures in the world.

The date when it is taken to end varies greatly between cultures,

and in many parts of the world there was no Iron Age at all, for

example in Pre-Columbian America and the prehistory of Australia. For these and other regions the three-age system is little used. By a convention among archaeologists, in the Ancient Near East the Iron Age is taken to end with the start of the Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BC, as the history of that is told by the Greek historian Herodotus.

This remains the case despite a good deal of earlier local written

material having become known since the convention was established. In

Western Europe the Iron Age is ended by Roman conquest. In South Asia

the start of the Maurya Empire

about 320 BC is usually taken as the end point; although we have a

considerable quantity of earlier written texts from India, they give us

relatively little in the way of a conventional record of political

history. For Egypt, China and Greece "Iron Age" is not a very useful

concept, and relatively little used as a period term. In the first two

prehistory has ended, and periodization by historical ruling dynasties

has already begun, in the Bronze Age, which these cultures do have. In

Greece the Iron Age begins during the Greek Dark Ages, and coincides with the cessation of a historical record for some centuries. For Scandinavia and other parts of northern Europe that the Romans did not reach, the Iron Age continues until the start of the Viking Age in about 800 AD.

Dating

The question of the dates of the objects and events discovered

through archaeology is the prime concern of any system of thought that

seeks to summarize history through the formulation of ages or epochs. An age is defined through comparison of contemporaneous events. Increasingly, the terminology of archaeology is parallel to that of historical method.

An event is "undocumented" until it turns up in the archaeological

record. Fossils and artifacts are "documents" of the epochs

hypothesized. The correction of dating errors is therefore a major

concern.

In the case where parallel epochs defined in history were available, elaborate efforts were made to align European and Near Eastern sequences with the datable chronology of Ancient Egypt

and other known civilizations. The resulting grand sequence was also

spot checked by evidence of calculateable solar or other astronomical

events.

These methods are only available for the relatively short term of

recorded history. Most prehistory does not fall into that category.

Physical science provides at least two general groups of dating

methods, stated below. Data collected by these methods is intended to

provide an absolute chronology to the framework of periods defined by

relative chronology.

Grand systems of layering

The initial comparisons of artifacts defined periods that were local to a site, group of sites or region.

Advances made in the fields of seriation, typology, stratification and the associative dating of artifacts

and features permitted even greater refinement of the system. The

ultimate development is the reconstruction of a global catalogue of

layers (or as close to it as possible) with different sections attested

in different regions. Ideally once the layer of the artifact or event is

known a quick lookup of the layer in the grand system will provide a

ready date. This is considered the most reliable method. It is used for

calibration of the less reliable chemical methods.

Measurement of chemical change

Any

material sample contains elements and compounds that are subject to

decay into other elements and compounds. In cases where the rate of

decay is predictable and the proportions of initial and end products can

be known exactly, consistent dates of the artifact can be calculated.

Due to the problem of sample contamination and variability of the

natural proportions of the materials in the media, sample analysis in

the case where verification can be checked by grand layering systems has

often been found to be widely inaccurate. Chemical dates therefore are

only considered reliable used in conjunction with other methods. They

are collected in groups of data points that form a pattern when graphed.

Isolated dates are not considered reliable.

Other -liths and -lithics

The term Megalithic does not refer to a period of time, but merely describes the use of large stones by ancient peoples from any period. An eolith

is a stone that might have been formed by natural process but occurs in

contexts that suggest modification by early humans or other primates

for percussion.

Criticism

The

Three-age System has been criticized since at least the 19th century.

Every phase of its development has been contested. Some of the arguments

that have been presented against it follow.

Unsound epochalism

In some cases criticism resulted in other, parallel three-age systems, such as the concepts expressed by Lewis Henry Morgan in Ancient Society, based on ethnology. These disagreed with the metallic basis of epochization. The critic generally substituted his own definitions of epochs. Vere Gordon Childe said of the early cultural anthropologists:

Last century Herbert Spencer, Lewis H. Morgan and Tylor propounded divergent schemes ... they arranged these in a logical order .... They assumed that the logical order was a temporal one.... The competing systems of Morgan and Tylor remained equally unverified—and incompatible—theories.

More recently, many archaeologists have questioned the validity of

dividing time into epochs at all. For example, one recent critic, Graham

Connah, describes the three-age system as "epochalism" and asserts:

So many archaeological writers have used this model for so long that for many readers it has taken on a reality of its own. In spite of the theoretical agonizing of the last half-century, epochalism is still alive and well ... Even in parts of the world where the model is still in common use, it needs to be accepted that, for example, there never was actually such a thing as 'the Bronze Age.'

Simplisticism

Some view the three-age system as over-simple; that is, it neglects

vital detail and forces complex circumstances into a mold they do not

fit. Rowlands argues that the division of human societies into epochs

based on the presumption of a single set of related changes is not

realistic:

But as a more rigorous sociological approach has begun to show that changes at the economic, political and ideological levels are not 'all of apiece' we have come to realise that time may be segmented in as many ways as convenient to the researcher concerned.

The three-age system is a relative chronology.

The explosion of archaeological data acquired in the 20th century was

intended to elucidate the relative chronology in detail. One consequence

was the collection of absolute dates. Connah argues:

As radiocarbon and other forms of absolute dating contributed more detailed and more reliable chronologies, the epochal model ceased to be necessary.

Peter Bogucki of Princeton University summarizes the perspective taken by many modern archaeologists:

Although modern archaeologists realize that this tripartite division of prehistoric society is far too simple to reflect the complexity of change and continuity, terms like 'Bronze Age' are still used as a very general way of focusing attention on particular times and places and thus facilitating archaeological discussion.

Eurocentrism

Another

common criticism attacks the broader application of the three-age

system as a cross-cultural model for social change. The model was

originally designed to explain data from Europe and West Asia, but

archaeologists have also attempted to use it to explain social and

technological developments in other parts of the world such as the

Americas, Australasia, and Africa. Many archaeologists working in these regions have criticized this application as eurocentric. Graham Connah writes that:

... attempts by Eurocentric archaeologists to apply the model to African archaeology have produced little more than confusion, whereas in the Americas or Australasia it has been irrelevant, ...

Alice B. Kehoe further explains this position as it relates to American archaeology:

... Professor Wilson's presentation of prehistoric archaeology was a European product carried across the Atlantic to promote an American science compatible with its European model.

Kehoe goes on to complain of Wilson that "he accepted and reprised

the idea that the European course of development was paradigmatic for

humankind."

This criticism argues that the different societies of the world

underwent social and technological developments in different ways. A

sequence of events that describes the developments of one civilization

may not necessarily apply to another, in this view. Instead social and

technological developments must be described within the context of the

society being studied.