Δελφοί

| |

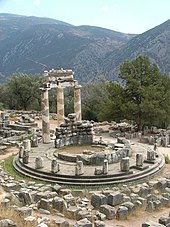

The Delphic Tholos, seen from above.

| |

| Location | Phocis, Greece |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°28′56″N 22°30′05″ECoordinates: 38°28′56″N 22°30′05″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Ancient Greece |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Delphi |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv and vi |

| Designated | 1987 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 393 |

| State Party | Greece |

| Region | Europe |

Delphi (/ˈdɛlfaɪ, ˈdɛlfi/; Greek: Δελφοί [ðelˈfi]), formerly also called Pytho (Πυθώ), is the ancient sanctuary that grew rich as the seat of Pythia, the oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The ancient Greeks considered the centre of the world to be in Delphi, marked by the stone monument known as the omphalos (navel).

It occupies a site on the south-western slope of Mount Parnassus, overlooking the coastal plain to the south and the valley of Phocis. It is now an extensive archaeological site with a small modern town of the same name nearby. It is recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in having had a great influence in the ancient world, as evidenced by the various monuments built there by most of the important ancient Greek city-states, demonstrating their fundamental Hellenic unity.

Origins and location

Delphi among the main Greek sanctuaries

Delphi is located in upper central Greece, on multiple plateaux along the slope of Mount Parnassus, and includes the Sanctuary of Apollo (the god of light, knowledge and harmony), the site of the ancient Oracle. This semicircular spur is known as Phaedriades, and overlooks the Pleistos Valley.

In myths dating to the classical period of Ancient Greece (510–323 BC), Zeus determined the site of Delphi when he sought to find the centre of his "Grandmother Earth" (Gaia). He sent two eagles flying from the eastern and western extremities, and the path of the eagles crossed over Delphi where the omphalos, or navel of Gaia was found.

Earlier myths include traditions that Pythia,

or the Delphic oracle, already was the site of an important oracle in

the pre-classical Greek world (as early as 1400 BC) and, rededicated

from about 800 BC, when it served as the major site during classical

times for the worship of the god Apollo. Apollo was said to have slain Python, a "drako" a serpent or a dragon who lived there and protected the navel of the Earth. "Python" (derived from the verb πύθω (pythō), "to rot") is claimed by some to be the original name of the site in recognition of Python which Apollo defeated. The Homeric Hymn to Delphic Apollo recalled that the ancient name of this site had been Krisa. Others relate that it was named Pytho

(Πυθώ) and that Pythia, the priestess serving as the oracle, was chosen

from their ranks by a group of priestesses who officiated at the

temple.

Excavation at Delphi, which was a post-Mycenaean settlement of

the late 9th century, has uncovered artifacts increasing steadily in

volume beginning with the last quarter of the 8th century BC. Pottery

and bronze as well as tripod dedications continue in a steady stream, in

contrast to Olympia.

Neither the range of objects nor the presence of prestigious

dedications proves that Delphi was a focus of attention for a wide range

of worshippers, but the large quantity of valuable goods, found in no

other mainland sanctuary, encourages that view.

Apollo's sacred precinct in Delphi was a panhellenic sanctuary, where every four years, starting in 586 BC athletes from all over the Greek world competed in the Pythian Games, one of the four Panhellenic Games, precursors of the Modern Olympics. The victors at Delphi were presented with a laurel crown (stephanos) which was ceremonially cut from a tree by a boy who re-enacted the slaying of the Python.

(These competitions are also called stephantic games, after the crown.)

Delphi was set apart from the other games sites because it hosted the

mousikos agon, musical competitions.

These Pythian Games rank second among the four stephanitic games chronologically and in importance.

These games, though, were different from the games at Olympia in that

they were not of such vast importance to the city of Delphi as the games

at Olympia were to the area surrounding Olympia. Delphi would have been

a renowned city regardless of whether it hosted these games; it had

other attractions that led to it being labeled the "omphalos" (navel) of

the earth, in other words, the centre of the world.

In the inner hestia (hearth) of the Temple of Apollo, an eternal flame burned. After the battle of Plataea, the Greek cities extinguished their fires and brought new fire from the hearth of Greece, at Delphi; in the foundation stories of several Greek colonies, the founding colonists were first dedicated at Delphi.

Religious significance

Ruins of the ancient temple of Apollo at Delphi, overlooking the valley of Phocis.

The name Delphi comes from the same root as δελφύς delphys, "womb" and may indicate archaic veneration of Gaia at the site. Apollo is connected with the site by his epithet Δελφίνιος Delphinios, "the Delphinian". The epithet is connected with dolphins (Greek δελφίς,-ῖνος) in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (line 400), recounting the legend of how Apollo first came to Delphi in the shape of a dolphin, carrying Cretan priests on his back. The Homeric name of the oracle is Pytho (Πυθώ). Another legend held that Apollo walked to Delphi from the north and stopped at Tempe, a city in Thessaly, to pick laurel (also known as bay tree)

which he considered to be a sacred plant. In commemoration of this

legend, the winners at the Pythian Games received a wreath of laurel

picked in the temple.

Delphi became the site of a major temple to Phoebus Apollo,

as well as the Pythian Games and the prehistoric oracle. Even in Roman

times, hundreds of votive statues remained, described by Pliny the Younger and seen by Pausanias. Carved into the temple were three phrases: γνῶθι σεαυτόν (gnōthi seautón = "know thyself") and μηδὲν ἄγαν (mēdén ágan = "nothing in excess"), and Ἑγγύα πάρα δ'ἄτη (engýa pára d'atē = "make a pledge and mischief is nigh"), In antiquity, the origin of these phrases was attributed to one or more of the Seven Sages of Greece by authors such as Plato and Pausanias. Additionally, according to Plutarch's essay on the meaning of the "E at Delphi"—the only literary source for the inscription—there was also inscribed at the temple a large letter E. Among other things epsilon signifies the number 5. However, ancient as well as modern scholars have doubted the legitimacy of such inscriptions.

According to one pair of scholars, "The actual authorship of the three

maxims set up on the Delphian temple may be left uncertain. Most likely

they were popular proverbs, which tended later to be attributed to

particular sages."

According to the Homeric hymn to the Pythian Apollo, Apollo shot

his first arrow as an infant which effectively slew the serpent Pytho,

the son of Gaia, who guarded the spot. To atone the murder of Gaia's

son, Apollo was forced to fly and spend eight years in menial service

before he could return forgiven. A festival, the Septeria, was held

every year, at which the whole story was represented: the slaying of the

serpent, and the flight, atonement, and return of the god.

The Pythian Games took place every four years to commemorate Apollo's victory. Another regular Delphi festival was the "Theophania" (Θεοφάνεια), an annual festival in spring celebrating the return of Apollo from his winter quarters in Hyperborea. The culmination of the festival was a display of an image of the gods, usually hidden in the sanctuary, to worshippers.

The theoxenia was held each summer, centred on a feast for

"gods and ambassadors from other states." Myths indicate that Apollo

killed the chthonic serpent Python guarding the Castalian Spring and named his priestess Pythia after her. Python, who had been sent by Hera, had attempted to prevent Leto, while she was pregnant with Apollo and Artemis, from giving birth.

This spring flowed toward the temple but disappeared beneath,

creating a cleft which emitted chemical vapors that purportedly caused

the oracle at Delphi to reveal her prophecies. Apollo killed Python but

had to be punished for it, since he was a child of Gaia. The shrine

dedicated to Apollo was originally dedicated to Gaia and shared with Poseidon. The name Pythia remained as the title of the Delphic oracle.

Erwin Rohde wrote that the Python was an earth spirit, who was conquered by Apollo, and buried under the omphalos, and that it is a case of one deity setting up a temple on the grave of another. Another view holds that Apollo was a fairly recent addition to the Greek pantheon coming originally from Lydia. The Etruscans coming from northern Anatolia also worshipped Apollo, and it may be that he was originally identical with Mesopotamian Aplu, an Akkadian title meaning "son", originally given to the plague God Nergal, son of Enlil. Apollo Smintheus (Greek Απόλλων Σμινθεύς), the mouse killer eliminates mice, a primary cause of disease, hence he promotes preventive medicine.

Oracle of Delphi

Delphi is perhaps best known for its oracle, the Pythia, the sibyl or priestess at the sanctuary dedicated to Apollo. According to Aeschylus in the prologue of the Eumenides, the oracle had origins in prehistoric times and the worship of Gaea, a view echoed by H.W. Parke.

One tale of the sanctuary's discovery states that a goatherd, who

grazed his flocks on Parnassus, one day observed his goats playing with

great agility upon nearing a chasm in the rock; the goatherd noticing

this held his head over the chasm causing the fumes to go to his brain;

throwing him into a strange trance.

Apollo

spoke through his oracle. She had to be an older woman of blameless

life chosen from among the peasants of the area. Alone in an enclosed

inner sanctum (Ancient Greek adyton - "do not enter") she sat on a

tripod seat over an opening in the earth (the "chasm"). According to

legend, when Apollo slew Python its body fell into this fissure and

fumes arose from its decomposing body. Intoxicated by the vapours, the

sibyl would fall into a trance, allowing Apollo to possess her spirit.

In this state she prophesied. The oracle could not be consulted during

the winter months, for this was traditionally the time when Apollo would

live among the Hyperboreans. Dionysus would inhabit the temple during his absence.

The time to consult pythia for an oracle during the year is

determined from astronomical and geological grounds related to the

constellations of Lyra and Cygnus but the hydrocarbon vapours emitted from the chasm. Similar practice was followed in other Apollo oracles too.

While in a trance the Pythia "raved" – probably a form of

ecstatic speech – and her ravings were "translated" by the priests of

the temple into elegant hexameters. It has been speculated that the

ancient writers, including Plutarch who had worked as a priest at Delphi, were correct in attributing the oracular effects to the sweet-smelling pneuma

(Ancient Greek for breath, wind or vapour) escaping from the chasm in

the rock. That exhalation could have been high in the known anaesthetic

and sweet-smelling ethylene or other hydrocarbons such as ethane known to produce violent trances. Though this theory remains debatable the authors put up a detailed answer to their critics.

Ancient sources describe the priestess using “laurel” to inspire her prophecies. Several alternative plant candidates have been suggested including Cannabis, Hyoscyamus, Rhododendron and Oleander. Harissis claims that a review of contemporary toxicological literature indicates that oleander

causes symptoms similar to those shown by the Pythia, and his study of

ancient texts shows that oleander was often included under the term

"laurel". The Pythia may have chewed oleander leaves and inhaled their

smoke prior to her oracular pronouncements and sometimes dying from the

toxicity. The toxic substances of oleander resulted in symptoms similar

to those of epilepsy, the “sacred disease,” which may have been seen as

the possession of the Pythia by the spirit of Apollo.

Fresco of Delphic sibyl painted by Michaelangelo at the Sistine Chapel.

The Delphic oracle exerted considerable influence throughout the

Greek world, and she was consulted before all major undertakings

including wars and the founding of colonies. She also was respected by the Greek-influenced countries around the periphery of the Greek world, such as Lydia, Caria, and even Egypt.

The oracle was also known to the early Romans. Rome's seventh and last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, after witnessing a snake near his palace, sent a delegation including two of his sons to consult the oracle.

In 83 BCE a Thracian tribe raided Delphi, burned the temple,

plundered the sanctuary and stole the "unquenchable fire" from the

altar. During the raid, part of the temple roof collapsed.

The same year, the temple was severely damaged by an earthquake, thus

it fell into decay and the surrounding area became impoverished. The

sparse local population led to difficulties in filling the posts

required. The oracle's credibility waned due to doubtful predictions.

The oracle flourished again in the second century CE during the rule of emperor Hadrian, who is believed to have visited the oracle twice and offered complete autonomy to the city.

By the 4th century, Delphi had acquired the status of a city. Constantine the Great looted several monuments, most notably the Tripod of Plataea, which he used to decorate his new capital, Constantinople.

Despite the rise of Christianity across the Roman Empire, the

oracle remained a religious centre throughout the 4th century, and the

Pythian Games continued to be held at least until 424 CE; however, the decline continued. The attempt of Emperor Julian to revive polytheism did not survive his reign. Excavations have revealed a large three-aisled basilica in the city, as well as traces of a church building in the sanctuary's gymnasium.

The site was abandoned in the 6th or 7th centuries, although a single

bishop of Delphi is attested in an episcopal list of the late 8th and

early 9th centuries.

History

Ancient Delphi

Speculative illustration of ancient Delphi by French architect Albert Tournaire.

Delphi was since ancient times a place of worship for Gaia, the mother goddess

connected with fertility. The town started to gain pan-Hellenic

relevance as both a shrine and an oracle in the 7th century BC.

Initially under the control of Phocaean settlers based in nearby Kirra (currently Itea), Delphi was reclaimed by the Athenians during the First Sacred War (597–585 BC). The conflict resulted in the consolidation of the Amphictyonic League, which had both a military and a religious function revolving around the protection of the Temple of Apollo. This shrine was destroyed by fire in 548 BC and then fell under the control of the Alcmaeonids banned from Athens. In 449–448 BC, the Second Sacred War (fought in the wider context of the First Peloponnesian War between the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta and the Delian-Attic League led by Athens) resulted in the Phocians gaining control of Delphi and the management of the Pythian Games.

In 356 BC the Phocians under Philomelos captured and sacked Delphi, leading to the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC), which ended with the defeat of the former and the rise of Macedon under the reign of Philip II. This led to the Fourth Sacred War (339 BC), which culminated in the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC) and the establishment of Macedonian rule over Greece.

In Delphi, Macedonian rule was superseded by the Aetolians in 279 BC, when a Gallic invasion was repelled, and by the Romans in 191 BC. The site was sacked by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 86 BC, during the Mithridatic Wars, and by Nero in 66 AD. Although subsequent Roman emperors of the Flavian dynasty contributed towards to the restoration of the site, it gradually lost importance. In the course of the 3rd century mystery cults became more popular than the traditional Greek pantheon. Christianity, which started as yet one more mystery cult, soon gained ground, and this eventually resulted in the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire. The anti-pagan legislation of the Flavian dynasty deprived ancient sanctuaries of their assets. The emperor Julian attempted to reverse this religious climate, yet his "pagan revival" was particularly short-lived. When the doctor Oreibasius visited the oracle of Delphi, in order to question the fate of paganism,he received a pessimistic answer:

Εἴπατε τῷ βασιλεῖ, χαμαὶ πέσε δαίδαλος αὐλά,

οὐκέτι Φοῖβος ἔχει καλύβην, οὐ μάντιδα δάφνην,

οὐ παγὰν λαλέουσαν, ἀπέσβετο καὶ λάλον ὕδωρ.

οὐκέτι Φοῖβος ἔχει καλύβην, οὐ μάντιδα δάφνην,

οὐ παγὰν λαλέουσαν, ἀπέσβετο καὶ λάλον ὕδωρ.

[Tell the king that the flute has fallen to the ground. Phoebus does

not have a home any more, neither an oracular laurel, nor a speaking

fountain, because the talking water has dried out.]

It was shut down during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire by Theodosius I in 381 AD.

Abandonment and rediscovery

Section of the frieze from the Treasury of the Siphnians, now in the museum.

The Ottomans finalized their domination over Phocis

and Delphi in about 1410CE. Delphi itself remained almost uninhabited

for centuries. It seems that one of the first buildings of the early

modern era was the monastery of the Dormition of Mary or of Panagia (the Mother of God) built above the ancient gymnasium at Delphi.

It must have been towards the end of the 15th or in the 16th century

that a settlement started forming there, which eventually ended up

forming the village of Kastri.

Ottoman Delphi gradually began to be investigated. The first Westerner to describe the remains in Delphi was Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli

(Cyriacus of Ancona), a 15th-century merchant turned diplomat and

antiquarian. He visited Delphi in March 1436 and remained there for six

days. He recorded all the visible archaeological remains based on Pausanias

for identification. He described the stadium and the theatre at that

date as well as some free standing pieces of sculpture. He also recorded

several inscriptions, most of which are now lost. His identifications

however were not always correct: for example he described a round

building he saw as the temple of Apollo while this was simply the base of the Argives' ex-voto. A severe earthquake in 1500 caused much damage.

In 1766 an English expedition funded by the Society of Dilettanti included the Oxford epigraphist Richard Chandler, the architect Nicholas Revett, and the painter William Pars. Their studies were published in 1769 under the title Ionian Antiquities, followed by a collection of inscriptions, and two travel books, one about Asia Minor (1775), and one about Greece (1776).

Apart from the antiquities, they also related some vivid descriptions

of daily life in Kastri, such as the crude behaviour of the

Turco-Albanians who guarded the mountain passes.

In 1805 Edward Dodwell visited Delphi, accompanied by the painter Simone Pomardi. Lord Byron visited in 1809, accompanied by his friend John Cam Hobhouse:

Yet there I've wandered by the vaulted rill;

Yes! Sighed o'er Delphi's long deserted shrine,

where, save that feeble fountain, all is still.

Yes! Sighed o'er Delphi's long deserted shrine,

where, save that feeble fountain, all is still.

He carved his name on the same column in the gymnasium as Lord Aberdeen,

later Prime Minister, who had visited a few years before. Proper

excavation did not start until the late 19th century (see "Excavations"

section) after the village had moved.

Buildings and structures

Site plan of the Sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi.

Occupation of the site at Delphi can be traced back to the Neolithic

period with extensive occupation and use beginning in the Mycenaean

period (1600–1100 BC). Most of the ruins that survive today date from

the most intense period of activity at the site in the 6th century BC.

Temple of Apollo

The ruins of the Temple of Delphi visible today date from the 4th century BC, and are of a peripteral Doric building. It was erected by Spintharus,

Xenodoros, and Agathon on the remains of an earlier temple, dated to

the 6th century BC which itself was erected on the site of a

7th-century BC construction attributed to the architects Trophonios and

Agamedes.

Amphictyonic Council

The Amphictyonic Council

was a council of representatives from six Greek tribes that controlled

Delphi and also the quadrennial Pythian Games. They met biannually and

came from Thessaly and central Greece. Over time, the town of Delphi

gained more control of itself and the council lost much of its

influence.

Treasuries

The reconstructed Treasury of Athens, built to commemorate their victory at the Battle of Marathon.

From the entrance of the site, continuing up the slope almost to the temple itself, are a large number of votive

statues, and numerous so-called treasuries. These were built by many of

the Greek city states to commemorate victories and to thank the oracle

for her advice which was thought to have contributed to those victories.

These buildings held the rich offerings made to Apollo; these were

frequently a "tithe" or tenth of the spoils of a battle. The most

impressive is the now-restored Athenian Treasury, built to commemorate their victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.

The Siphnian Treasury was dedicated by the city of Siphnos

whose citizens gave a tithe of the yield from their silver mines until

the mines came to an abrupt end when the sea flooded the workings.

One of the largest of the treasuries was that of Argos. Built in

the late Doric period, the Argives took great pride in establishing

their place amongst the other city states. Completed in 380 BC, the

treasury draws inspiration mostly from the Temple of Hera located in the

Argolis, the acropolis of the city. However, recent analysis of the

Archaic elements of the treasury suggest that its founding preceded

this.

Altar of the Chians

Located in front of the Temple of Apollo, the main altar of the sanctuary was paid for and built by the people of Chios. It is dated to the 5th century BC by the inscription on its cornice.

Made entirely of black marble, except for the base and cornice, the

altar would have made a striking impression. It was restored in 1920.

Stoa of the Athenians

View of the Athenian Treasury; the Stoa of the Athenians on the right.

The stoa leads off north-east from the main sanctuary. It was built in the Ionic order

and consists of seven fluted columns, unusually carved from single

pieces of stone (most columns were constructed from a series of discs

joined together). The inscription on the stylobate

indicates that it was built by the Athenians after their naval victory

over the Persians in 478 BC, to house their war trophies. The stoa was

attached to the existing Polygonal Wall.

Sibyl rock

The Sibyl rock is a pulpit-like outcrop of rock between the Athenian Treasury and the Stoa of the Athenians upon the sacred way which leads up to the temple of Apollo

in the archaeological area of Delphi. It is claimed to be where an

ancient Sibyl pre-dating the Pythia of Apollo sat to deliver her

prophecies.

Theatre

The theatre at Delphi (as viewed near the top seats)

The ancient theatre

at Delphi was built further up the hill from the Temple of Apollo

giving spectators a view of the entire sanctuary and the valley below.

It was originally built in the 4th century BC but was remodeled on

several occasions, particularly in 160/159 B.C. at the expenses of king

Eumenes II of Pergamon and in 67 A.D. on the occasion of emperor Nero's

visit.

The koilon (cavea) leans against the natural slope of the mountain

whereas its eastern part overrides a little torrent which led the water

of the fountain Cassotis right underneath the temple of Apollo. The

orchestra was initially a full circle with a diameter measuring 7

meters. The rectangular scene building ended up in two arched openings,

of which the foundations are preserved today. Access to the theatre was

possible through the parodoi, i.e. the side corridors. On the support

walls of the parodoi are engraved large numbers of manumission inscriptions

recording fictitious sales of the slaves to the god.

The koilon was divided horizontally in two zones via a corridor called

diazoma. The lower zone had 27 rows of seats and the upper one only 8.

Six radially arranged stairs divided the lower part of the koilon in

seven tiers. The theatre could accommodate about 4,500 spectators.

On the occasion of Nero's visit to Greece in 67 A.D. various

alterations took place. The orchestra was paved and delimited by a

parapet made of stone. The proscenium was replaced by a low pedestal,

the pulpitum; its façade was decorated with scenes from Hercules' myth

in relief. Further repairs and transformations took place in the 2nd

century A.D. Pausanias mentions that these were carried out under the

auspices of Herod Atticus.

In antiquity, the theatre was used for the vocal and musical contests

which formed part of the programme of the Pythian Games in the late

Hellenistic and Roman period.

The theatre was abandoned when the sanctuary declined in Late

Antiquity. After its excavation and initial restoration it hosted

theatrical performances during the Delphic Festivals organized by A.

Sikelianos and his wife, Eva Palmer, in 1927 and in 1930. It has

recently been restored again as the serious landslides posed a grave

threat for its stability for decades.

Tholos

Athena Pronaia Sanctuary at Delphi

The Tholos at the sanctuary of Athena Pronoia

(Ἀθηνᾶ Πρόνοια, "Athena of forethought") is a circular building that

was constructed between 380 and 360 BC. It consisted of 20 Doric columns arranged with an exterior diameter of 14.76 meters, with 10 Corinthian columns in the interior.

The Tholos is located approximately a half a mile (800 m) from the main ruins at Delphi (at 38°28′49″N 22°30′28″E). Three of the Doric columns have been restored, making it the most popular site at Delphi for tourists to take photographs.

The architect of the "vaulted temple at Delphi" is named by Vitruvius, in De architectura Book VII, as Theodorus Phoceus (not Theodorus of Samos, whom Vitruvius names separately).

Gymnasium

The gymnasium

The gymnasium,

which is half a mile away from the main sanctuary, was a series of

buildings used by the youth of Delphi. The building consisted of two

levels: a stoa on the upper level providing open space, and a palaestra,

pool and baths on lower floor. These pools and baths were said to have

magical powers, and imparted the ability to communicate to Apollo

himself.

Stadium

The mountain-top stadium at Delphi, far above the temples-theater below

The stadium is located further up the hill, beyond the via sacra

and the theatre. It was originally built in the 5th century BC but was

altered in later centuries. The last major remodelling took place in the

2nd century AD under the patronage of Herodes Atticus

when the stone seating was built and (arched) entrance. It could seat

6500 spectators and the track was 177 metres long and 25.5 metres wide.

Hippodrome

It was at the Pythian games that prominent political leaders, such as Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sikyon, and Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse, competed with their chariots. The hippodrome where these events took place was referred to by Pindar, and this monument was sought by archaeologists for over two centuries.

Its traces have recently been found at Gonia in the plain of Krisa in the place where the original stadium was sited.

Polygonal wall

Section of polygonal wall at Delphi, behind a pillar from the Athenian Stoa

The retaining wall was built to support the terrace housing the

construction of the second temple of Apollo in 548 BC. Its name is taken

from the polygonal masonry of which it is constructed. At a later date, from 200 BC onwards, the stones were inscribed with the manumission contracts of slaves who were consecrated to Apollo. Approximately a thousand manumissions are recorded on the wall.

Castalian spring

The sacred spring of Delphi lies in the ravine of the Phaedriades.

The preserved remains of two monumental fountains that received the

water from the spring date to the Archaic period and the Roman, with the latter cut into the rock.

Athletic statues

Delphi

is famous for its many preserved athletic statues. It is known that

Olympia originally housed far more of these statues, but time brought

ruin to many of them, leaving Delphi as the main site of athletic

statues. Kleobis and Biton,

two brothers renowned for their strength, are modeled in two of the

earliest known athletic statues at Delphi. The statues commemorate their

feat of pulling their mother's cart several miles to the Sanctuary of

Hera in the absence of oxen. The neighbors were most impressed and their

mother asked Hera to grant them the greatest gift. When they entered

Hera's temple, they fell into a slumber and never woke, dying at the

height of their admiration, the perfect gift.

The Charioteer of Delphi

is another ancient relic that has withstood the centuries. It is one of

the best known statues from antiquity. The charioteer has lost many

features, including his chariot and his left arm, but he stands as a

tribute to athletic art of antiquity.

The Charioteer of Delphi, 478 or 474 BC, Delphi Museum.

Architectural traditions

Ancient

tradition accounted for four temples that successively occupied the

site before the 548/7 BC fire, following which the Alcmaeonids built a

fifth. The poet Pindar celebrated the Alcmaeonid's temple in Pythian 7.8-9 and he also provided details of the third building (Paean 8. 65-75). Other details are given by Pausanias

(10.5.9-13) and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (294 ff.). The first temple

was said to have been constructed out of olive branches from Tempe. The second was made by bees out of wax and wings but was miraculously carried off by a powerful wind and deposited among the Hyperboreans. The third, as described by Pindar, was created by the gods Hephaestus and Athena, but its architectural details included Siren-like

figures or 'Enchantresses', whose baneful songs eventually provoked the

Olympian gods to bury the temple in the earth (according to Pausanias,

it was destroyed by earthquake and fire). In Pindar's words, addressed

to the Muses:

-

-

-

- Muses, what was its fashion, shown

- By the skill in all arts

- Of the hands of Hephaestus and Athena?

- Of bronze the walls, and of bronze

- Stood the pillars beneath,

- But of gold were six Enchantresses

- Who sang above the eagle.

- But the sons of Cronus

- Opened the earth with a thunderbolt

- And hid the holiest of all things made.

- Away from their children

- And wives, when they hung

- Their lives on the honey-hearted words.

-

-

The fourth temple was said to have been constructed from stone by Trophonius and Agamedes. However, a new theory gives a completely new explanation of the above myth of the four temples of Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum

Archaeological Museum of Delphi, designed by Alexandros Tombazis

The Delphi Archaeological Museum

is at the foot of the main archaeological complex, on the east side of

the village, and on the north side of the main road. The museum houses

an impressive collection associated with ancient Delphi, including the

earliest known notation of a melody, the famous Charioteer of Delphi, Kleobis and Biton, golden treasures discovered beneath the Sacred Way, the Sphinx of Naxos,

and fragments of reliefs from the Siphnian Treasury. Immediately

adjacent to the exit (and overlooked by most tour guides) is the

inscription that mentions the Roman proconsul Gallio.

Entries to the museum and to the main complex are separate and

chargeable, and a reduced rate ticket gets entry to both. There is a

small cafe, and a post office by the museum.

Excavations

The site had been occupied by the village of Kastri

since medieval times. Before a systematic excavation of the site could

be undertaken, the village had to be relocated but the residents

resisted. The opportunity to relocate the village occurred when it was

substantially damaged by an earthquake, with villagers offered a

completely new village in exchange for the old site. In 1893 the French Archaeological School

removed vast quantities of soil from numerous landslides to reveal both

the major buildings and structures of the sanctuary of Apollo and of

Athena Pronoia along with thousands of objects, inscriptions and

sculptures.

The site is now an archaeological one, and a very popular tourist

destination. It is easily accessible from Athens as a day trip, and is

often combined with the winter sports facilities available on Mount Parnassus, as well as the beaches and summer sports facilities of the nearby coast of Phocis.

The site is also protected as a site of extraordinary natural beauty, and the views from it are also protected:

no industrial artefacts are to be seen from Delphi other than roads and

traditional architecture residences (for example high voltage power

lines and the like are routed so as to be invisible from the area of the

sanctuary).

5th-century Delphi

During the Great Excavation were discovered architectural members from a 5th-century Christian basilica, when Delphi was a bishopric. Other important Late Roman buildings are the Eastern Baths, the house with the peristyle, the Roman Agora, the large cistern usw. At the outskirts of the city there were located late Roman cemeteries.

To the southeast of the precinct of Apollo lay the so-called

Southeastern Mansion, a building with a 65-meter-long façade, spread

over four levels, with four triclinia and private baths. Large storage

jars kept the provisions, whereas other pottery vessels and luxury items

were discovered in the rooms. Among the finds stands out a tiny leopard

made of mother of pearl, possibly of Sassanian origin, on display in

the ground floor gallery of the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

The mansion dates to the beginning of the 5th century and functioned as

a private house until 580, later however it was transformed into a

potters' workshop.

It is only then, in the beginning of the 6th century, that the city

seems to decline: its size is reduced and its trade contacts seem to be

drastically diminished. Local pottery production is produced in large

quantities: it is coarser and made of reddish clay, aiming at satisfying the needs of the inhabitants.

The Sacred Way remained the main street of the settlement,

transformed, however, into a street with commercial and industrial use.

Around the agora were built workshops as well as the only intra muros

early Christian basilica. The domestic area spread mainly in the western

part of the settlement. The houses were rather spacious and two large

cisterns provided running water to them.

Depiction in art

View of Delphi with Sacrificial Procession by Claude Lorrain

From the 16th century onward, West Europe developed an interest in

Delphi. In the mid-15th century Strabo was first translated in Latin.

The earliest depictions of Delphi were totally imaginary, created by the

German N. Gerbel, who published in 1545 a text based on the map of

Greece by N. Sofianos. The ancient sanctuary was depicted as a fortified

city.

The first travelers with archaeological interests, apart from the precursor Cyriacus of Ancona, were the British George Wheler and the French Jacob Spon,

who visited Greece in a joint expedition in 1675–1676. They published

their impressions separately. In Wheler's "Journey into Greece",

published in 1682, a sketch of the region of Delphi appeared, where the

settlement of Kastri and some ruins were depicted. The illustrations in

Spon's publication "Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grèce et du Levant,

1678" are considered original and groundbreaking.

Travelers continued to visit Delphi throughout the 19th century

and published their books which contained diaries, sketches, views of

the site as well as pictures of coins. The illustrations often reflected

the spirit of romanticism, as evident by the works of Otto Magnus von

Stackelberg, where, apart from the landscapes (La Grèce. Vues pittoresques et topographiques, Paris 1834) are depicted also human types (Costumes et usages des peuples de la Grèce moderne dessinés sur les lieux,

Paris 1828). The philhellene painter W. Williams has comprised the

landscape of Delphi in his themes (1829). Influential personalities such

as F.Ch.-H.-L. Pouqueville, W.M. Leake, Chr. Wordsworth and Lord Byron

are amongst the most important visitors of Delphi.

Delphi by Edward Lear features the Phaedriades.

After the foundation of the modern Greek state, the press became also

interested in these travelers. Thus "Ephemeris" writes (17 March 1889):

In the Revues des Deux Mondes Paul Lefaivre

published his memoirs from an excursion to Delphi. The French author

relates in a charming style his adventures on the road, praising

particularly the ability of an old woman to put back in place the

dislocated arm of one of his foreign traveling companions, who had

fallen off the horse. "In Arachova

the Greek type is preserved intact. The men are rather athletes than

farmers, built for running and wrestling, particularly elegant and

slender under their mountain gear." Only briefly does he refer to the

antiquities of Delphi, but he refers to a pelasgian wall 80 meters long,

"on which innumerable inscriptions are carved, decrees, conventions,

manumissions."

Gradually the first travelling guides appeared. The revolutionary "pocket" books invented by Karl Baedeker,

accompanied by maps useful for visiting archaeological sites such as

Delphi (1894) and the informed plans, the guides became practical and

popular. The photographic lens revolutionized the way of depicting the

landscape and the antiquities, particularly from 1893 onwards, when the

systematic excavations of the French Archaeological School started.

However, artists such as Vera Willoughby, continued to be inspired by

the landscape.

Delphic themes inspired several graphic artists. Besides the landscape, Pythia/Sibylla become an illustration subject even on Tarot cards. A famous example constitutes Michelangelo's Delphic Sibyl (1509),

the 19th-century German engraving Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, as well

as the recent ink on paper drawing "The Oracle of Delphi" (2013) by M.

Lind.

Modern artists are inspired also by the Delphic Maxims. Examples of such

works are displayed in the "Sculpture park of the European Cultural

Center of Delphi" and in exhibitions taking place at the Archaeological

Museum of Delphi.

In literature

Delphi inspired literature as well. In 1814 W. Haygarth, friend of

Lord Byron, refers to Delphi in his work "Greece, a Poem". In 1888 Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle published his lyric drama L’Apollonide, accompanied by music by Franz Servais. More recent French authors used Delphi as a source of inspiration such as Yves Bonnefoy (Delphes du second jour) or Jean Sullivan (nickname of Joseph Lemarchand) in L'Obsession de Delphes (1967), but also Rob MacGregor's Indiana Jones and the Peril at Delphi (1991).

The presence of Delphi in Greek literature is very intense. Poets such as Kostis Palamas (The Delphic Hymn, 1894), Kostas Karyotakis (Delphic festival, 1927), Nikephoros Vrettakos (return from Delphi, 1957), Yannis Ritsos (Delphi, 1961–62) and Kiki Dimoula (Gas omphalos and Appropriate terrain 1988), to mention only the most renowned ones. Angelos Sikelianos

wrote The Dedication (of the Delphic speech) (1927), the Delphic Hymn

(1927) and the tragedy Sibylla (1940), whereas in the context of the

Delphic idea and the Delphic festivals he published an essay titled "The

Delphic union" (1930). The nobelist George Seferis wrote an essay under the title "Delphi", in the book "Dokimes".

The importance of Delphi for the Greeks is significant. The site

has been recorded on the collective memory and have been expressed

through tradition. Nikolaos Politis,

the famous Greek ethnographer, in his Studies on the life and language

of the Greek people - part A, offers two examples from Delphi:

- a) the priest of Apollo (176)

When Christ was born a priest of Apollo was sacrificing below the

monastery of Panayia, on the road of Livadeia, on a site called Logari.

Suddenly he abandoned the sacrifice and says to the people: "in this

moment was born the son of God, who will be very powerful, like Apollo,

but then Apollo will beat him". He didn't have time to finish his speech

and a thunder came down and burnt him, opening the rock nearby into

two. [p. 99]

- b)The Mylords (108)

The Mylords are not Christians, because nobody ever saw them cross

themselves. They originate from the old pagan inhabitants of Delphi who

kept their property in castle called Adelphi, named after the two

brother princes who built it. When Christ and his mother came to the

site, and all people around converted to Christianity they thought that

they should better leave; thus the Mylords left for the West and took

all their belongings with them. The Mylords come here now and worship

these stones. [p. 59]