American Progress, (1872) by John Gast, is an allegorical representation of the modernization of the new west. Columbia,

a personification of the United States, is shown leading civilization

westward with the American settlers. She is shown bringing light from

the East into the West, stringing telegraph wire, holding a school

textbook that will instill knowledge, and highlights different stages of economic activity and evolving forms of transportation.

In the 19th century, manifest destiny was a widely held belief in the United States that its settlers were destined to expand across North America. There are three basic themes to manifest destiny:

- The special virtues of the American people and their institutions

- The mission of the United States to redeem and remake the west in the image of agrarian America

- An irresistible destiny to accomplish this essential duty

Historian Frederick Merk

says this concept was born out of "a sense of mission to redeem the Old

World by high example ... generated by the potentialities of a new

earth for building a new heaven".

Historians have emphasized that "manifest destiny" was a contested concept—Democrats endorsed the idea but many prominent Americans (such as Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and most Whigs) rejected it. Historian Daniel Walker Howe

writes, "American imperialism did not represent an American consensus;

it provoked bitter dissent within the national polity ... Whigs saw America's moral mission as one of democratic example rather than one of conquest."

Newspaper editor John O'Sullivan is generally credited with coining the term manifest destiny in 1845 to describe the essence of this mindset, which was a rhetorical tone;

however, the unsigned editorial titled "Annexation" in which it first

appeared was arguably written by journalist and annexation advocate Jane Cazneau. The term was used by Democrats in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico and it was also used to divide half of Oregon with the United Kingdom.

But manifest destiny always limped along because of its internal

limitations and the issue of slavery, says Merk. It never became a

national priority. By 1843, former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, originally a major supporter of the concept underlying manifest destiny, had changed his mind and repudiated expansionism because it meant the expansion of slavery in Texas.

Merk concluded:

From the outset Manifest Destiny—vast in program, in its sense of continentalism—was slight in support. It lacked national, sectional, or party following commensurate with its magnitude. The reason was it did not reflect the national spirit. The thesis that it embodied nationalism, found in much historical writing, is backed by little real supporting evidence.

Context

There

was never a set of principles defining manifest destiny, therefore it

was always a general idea rather than a specific policy made with a

motto. Ill-defined but keenly felt, manifest destiny was an expression

of conviction in the morality and value of expansionism that

complemented other popular ideas of the era, including American exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism. Andrew Jackson,

who spoke of "extending the area of freedom", typified the conflation

of America's potential greatness, the nation's budding sense of Romantic

self-identity, and its expansion.

Yet Jackson would not be the only president to elaborate on the

principles underlying manifest destiny. Owing in part to the lack of a

definitive narrative outlining its rationale, proponents offered

divergent or seemingly conflicting viewpoints. While many writers

focused primarily upon American expansionism, be it into Mexico or

across the Pacific, others saw the term as a call to example. Without an

agreed upon interpretation, much less an elaborated political

philosophy, these conflicting views of America's destiny were never

resolved. This variety of possible meanings was summed up by Ernest Lee

Tuveson: "A vast complex of ideas, policies, and actions is comprehended

under the phrase "Manifest Destiny". They are not, as we should expect,

all compatible, nor do they come from any one source."

Origin of the term

John L. O'Sullivan,

sketched in 1874, was an influential columnist as a young man, but he

is now generally remembered only for his use of the phrase "manifest

destiny" to advocate the annexation of Texas and Oregon.

Journalist John L. O'Sullivan was an influential advocate for Jacksonian democracy and a complex character, described by Julian Hawthorne as "always full of grand and world-embracing schemes".

O'Sullivan wrote an article in 1839 that, while not using the term

"manifest destiny", did predict a "divine destiny" for the United States

based upon values such as equality, rights of conscience, and personal

enfranchisement "to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation

of man".

This destiny was not explicitly territorial, but O'Sullivan predicted

that the United States would be one of a "Union of many Republics"

sharing those values.

Six years later, in 1845, O'Sullivan wrote another essay titled Annexation in the Democratic Review, in which he first used the phrase manifest destiny. In this article he urged the U.S. to annex the Republic of Texas, not only because Texas desired this, but because it was "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions". Overcoming Whig opposition, Democrats annexed Texas in 1845. O'Sullivan's first usage of the phrase "manifest destiny" attracted little attention.

O'Sullivan's second use of the phrase became extremely influential. On December 27, 1845, in his newspaper the New York Morning News, O'Sullivan addressed the ongoing boundary dispute with Britain. O'Sullivan argued that the United States had the right to claim "the whole of Oregon":

And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.

That is, O'Sullivan believed that Providence had given the United States a mission to spread republican democracy

("the great experiment of liberty"). Because Britain would not spread

democracy, thought O'Sullivan, British claims to the territory should be

overruled. O'Sullivan believed that manifest destiny was a moral ideal

(a "higher law") that superseded other considerations.

O'Sullivan's original conception of manifest destiny was not a

call for territorial expansion by force. He believed that the expansion

of the United States would happen without the direction of the

U.S. government or the involvement of the military. After Americans

immigrated to new regions, they would set up new democratic governments,

and then seek admission to the United States, as Texas had done. In

1845, O'Sullivan predicted that California would follow this pattern

next, and that Canada would eventually request annexation as well. He

disapproved of the Mexican–American War in 1846, although he came to believe that the outcome would be beneficial to both countries.

Ironically, O'Sullivan's term became popular only after it was criticized by Whig opponents of the Polk administration.

Whigs denounced manifest destiny, arguing, "that the designers and

supporters of schemes of conquest, to be carried on by this government,

are engaged in treason to our Constitution and Declaration of Rights,

giving aid and comfort to the enemies of republicanism, in that they are

advocating and preaching the doctrine of the right of conquest". On January 3, 1846, Representative Robert Winthrop

ridiculed the concept in Congress, saying "I suppose the right of a

manifest destiny to spread will not be admitted to exist in any nation

except the universal Yankee nation". Winthrop was the first in a long

line of critics who suggested that advocates of manifest destiny were

citing "Divine Providence" for justification of actions that were

motivated by chauvinism and self-interest. Despite this criticism,

expansionists embraced the phrase, which caught on so quickly that its

origin was soon forgotten.

Themes and influences

Historian William E. Weeks has noted that three key themes were usually touched upon by advocates of manifest destiny:

- the virtue of the American people and their institutions;

- the mission to spread these institutions, thereby redeeming and remaking the world in the image of the United States;

- the destiny under God to do this work.

The origin of the first theme, later known as American exceptionalism, was often traced to America's Puritan heritage, particularly John Winthrop's famous "City upon a Hill" sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World. In his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, Thomas Paine echoed this notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society:

We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand ...

Many Americans agreed with Paine, and came to believe that the United

States' virtue was a result of its special experiment in freedom and

democracy. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to James Monroe,

wrote, "it is impossible not to look forward to distant times when our

rapid multiplication will expand itself beyond those limits, and cover

the whole northern, if not the southern continent."

To Americans in the decades that followed their proclaimed freedom for

mankind, embodied in the Declaration of Independence, could only be

described as the inauguration of "a new time scale" because the world

would look back and define history as events that took place before, and

after, the Declaration of Independence. It followed that Americans owed to the world an obligation to expand and preserve these beliefs.

The second theme's origination is less precise. A popular

expression of America's mission was elaborated by President Abraham

Lincoln's description in his December 1, 1862, message to Congress. He

described the United States as "the last, best hope of Earth". The

"mission" of the United States was further elaborated during Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, in which he interpreted the Civil War

as a struggle to determine if any nation with democratic ideals could

survive; this has been called by historian Robert Johannsen "the most

enduring statement of America's Manifest Destiny and mission".

The third theme can be viewed as a natural outgrowth of the

belief that God had a direct influence in the foundation and further

actions of the United States. Clinton Rossiter,

a scholar, described this view as summing "that God, at the proper

stage in the march of history, called forth certain hardy souls from the

old and privilege-ridden nations ... and that in bestowing his grace He

also bestowed a peculiar responsibility". Americans presupposed that

they were not only divinely elected to maintain the North American

continent, but also to "spread abroad the fundamental principles stated

in the Bill of Rights".

In many cases this meant neighboring colonial holdings and countries

were seen as obstacles rather than the destiny God had provided the

United States.

Faragher's analysis of the political polarization between the Democratic Party and the Whig Party is that:

Most Democrats were wholehearted supporters of expansion, whereas many Whigs (especially in the North) were opposed. Whigs welcomed most of the changes wrought by industrialization but advocated strong government policies that would guide growth and development within the country's existing boundaries; they feared (correctly) that expansion raised a contentious issue, the extension of slavery to the territories. On the other hand, many Democrats feared industrialization the Whigs welcomed... For many Democrats, the answer to the nation's social ills was to continue to follow Thomas Jefferson's vision of establishing agriculture in the new territories in order to counterbalance industrialization.

Another possible influence is racial predominance, namely the idea

that the American Anglo-Saxon race was "separate, innately superior" and

"destined to bring good government, commercial prosperity and

Christianity to the American continents and the world". This view also

held that "inferior races were doomed to subordinate status or

extinction." This was used to justify "the enslavement of the blacks and

the expulsion and possible extermination of the Indians".

Alternative interpretations

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which doubled the size of the United States, Thomas Jefferson set the stage for the continental expansion of the United States. Many began to see this as the beginning of a new providential mission: If the United States was successful as a "shining city upon a hill", people in other countries would seek to establish their own democratic republics.

However, not all Americans or their political leaders believed

that the United States was a divinely favored nation, or thought that it

ought to expand. For example, many Whigs

opposed territorial expansion based on the Democratic claim that the

United States was destined to serve as a virtuous example to the rest of

the world, and also had a divine obligation to spread its superordinate

political system and a way of life throughout North American continent.

Many in the Whig party "were fearful of spreading out too widely", and

they "adhered to the concentration of national authority in a limited

area". In July 1848, Alexander Stephens denounced President Polk's expansionist interpretation of America's future as "mendacious".

Ulysses S. Grant, served in the War with Mexico and later wrote:

- I was bitterly opposed to the measure [to annex Texas], and to this day regard the war [with Mexico] which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.

In the mid‑19th century, expansionism, especially southward toward

Cuba, also faced opposition from those Americans who were trying to

abolish slavery. As more territory was added to the United States in the

following decades, "extending the area of freedom" in the minds of

southerners also meant extending the institution of slavery. That is why

slavery became one of the central issues in the continental expansion

of the United States before the Civil War.

Before and during the Civil War both sides claimed that America's

destiny were rightfully their own. Lincoln opposed anti-immigrant nativism, and the imperialism of manifest destiny as both unjust and unreasonable.

He objected to the Mexican War and believed each of these disordered

forms of patriotism threatened the inseparable moral and fraternal bonds

of liberty and Union that he sought to perpetuate through a patriotic

love of country guided by wisdom and critical self-awareness. Lincoln's "Eulogy to Henry Clay", June 6, 1852, provides the most cogent expression of his reflective patriotism.

Era of continental expansion

John Quincy Adams, painted above in 1816 by Charles Robert Leslie,

was an early proponent of continentalism. Late in life he came to

regret his role in helping U.S. slavery to expand, and became a leading

opponent of the annexation of Texas.

The phrase "manifest destiny" is most often associated with the territorial expansion of the United States from 1812 to 1860. This era, from the end of the War of 1812 to the beginning of the American Civil War, has been called the "age of manifest destiny".

During this time, the United States expanded to the Pacific Ocean—"from

sea to shining sea"—largely defining the borders of the contiguous United States as they are today.

War of 1812

One of the goals of the War of 1812 was to threaten to annex British Canada in order to stop the Indian raids into the Midwest. The result of this overoptimism was a series of defeats in 1812. However, the American victories at the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of the Thames in 1813 ended the Indian raids and removed the main reason for threatening annexation. To end the War of 1812 John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and Albert Gallatin (former Treasury Secretary and a leading expert on Indians) and the other American diplomats negotiated the Treaty of Ghent

in 1814 with Britain. They rejected the British plan to set up an

Indian state in U.S. territory south of the Great Lakes. They explained

the American policy toward acquisition of Indian lands:

The United States, while intending never to acquire lands from the Indians otherwise than peaceably, and with their free consent, are fully determined, in that manner, progressively, and in proportion as their growing population may require, to reclaim from the state of nature, and to bring into cultivation every portion of the territory contained within their acknowledged boundaries. In thus providing for the support of millions of civilized beings, they will not violate any dictate of justice or of humanity; for they will not only give to the few thousand savages scattered over that territory an ample equivalent for any right they may surrender, but will always leave them the possession of lands more than they can cultivate, and more than adequate to their subsistence, comfort, and enjoyment, by cultivation. If this be a spirit of aggrandizement, the undersigned are prepared to admit, in that sense, its existence; but they must deny that it affords the slightest proof of an intention not to respect the boundaries between them and European nations, or of a desire to encroach upon the territories of Great Britain ... They will not suppose that that Government will avow, as the basis of their policy towards the United States a system of arresting their natural growth within their own territories, for the sake of preserving a perpetual desert for savages.

A shocked Henry Goulburn,

one of the British negotiators at Ghent, remarked, after coming to

understand the American position on taking the Indians' land:

Till I came here, I had no idea of the fixed determination which there is in the heart of every American to extirpate the Indians and appropriate their territory.

Continentalism

The 19th-century belief that the United States would eventually encompass all of North America is known as "continentalism", a form of tellurocracy. An early proponent of this idea, John Quincy Adams, became a leading figure in U.S. expansion between the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the Polk administration in the 1840s. In 1811, Adams wrote to his father:

The whole continent of North America appears to be destined by Divine Providence to be peopled by one nation, speaking one language, professing one general system of religious and political principles, and accustomed to one general tenor of social usages and customs. For the common happiness of them all, for their peace and prosperity, I believe it is indispensable that they should be associated in one federal Union.

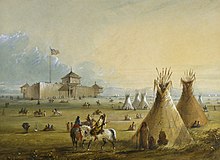

The first Fort Laramie as it looked prior to 1840. Painting from memory by Alfred Jacob Miller

Adams did much to further this idea. He orchestrated the Treaty of 1818, which established the Canada–US border as far west as the Rocky Mountains, and provided for the joint occupation of the region known in American history as the Oregon Country and in British and Canadian history as the New Caledonia and Columbia Districts. He negotiated the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819, transferring Florida

from Spain to the United States and extending the U.S. border with

Spanish Mexico all the way to the Pacific Ocean. And he formulated the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which warned Europe that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open for European colonization.

The Monroe Doctrine and "manifest destiny" formed a closely

related nexus of principles: historian Walter McDougall calls manifest

destiny a corollary of the Monroe Doctrine, because while the Monroe

Doctrine did not specify expansion, expansion was necessary in order to

enforce the Doctrine. Concerns in the United States that European powers

(especially Great Britain) were seeking to acquire colonies or greater

influence in North America led to calls for expansion in order to

prevent this. In his influential 1935 study of manifest destiny, Albert

Weinberg wrote: "the expansionism of the [1830s] arose as a defensive

effort to forestall the encroachment of Europe in North America".

All Oregon

Manifest destiny played its most important role in the Oregon boundary dispute between the United States and Britain, when the phrase "manifest destiny" originated. The Anglo-American Convention of 1818 had provided for the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, and thousands of Americans migrated there in the 1840s over the Oregon Trail. The British rejected a proposal by U.S. President John Tyler (in office 1841–1845) to divide the region along the 49th parallel, and instead proposed a boundary line farther south along the Columbia River, which would have made most of what later became the state of Washington

part of British North America. Advocates of manifest destiny protested

and called for the annexation of the entire Oregon Country up to the Alaska line (54°40ʹ N). Presidential candidate James K. Polk used this popular outcry to his advantage, and the Democrats called for the annexation of "All Oregon" in the 1844 U.S. Presidential election.

American westward expansion is idealized in Emanuel Leutze's famous painting Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (1861). The title of the painting, from a 1726 poem by Bishop Berkeley,

was a phrase often quoted in the era of manifest destiny, expressing a

widely held belief that civilization had steadily moved westward

throughout history. (more)

As president, however, Polk sought compromise and renewed the earlier

offer to divide the territory in half along the 49th parallel, to the

dismay of the most ardent advocates of manifest destiny. When the

British refused the offer, American expansionists responded with slogans

such as "The Whole of Oregon or None!" and "Fifty-Four Forty or

Fight!", referring to the northern border of the region. (The latter

slogan is often mistakenly described as having been a part of the 1844

presidential campaign.) When Polk moved to terminate the joint

occupation agreement, the British finally agreed in early 1846 to divide

the region along the 49th parallel, leaving the lower Columbia basin as

part of the United States. The Oregon Treaty

of 1846 formally settled the dispute; Polk's administration succeeded

in selling the treaty to Congress because the United States was about to

begin the Mexican–American War, and the president and others argued it would be foolish to also fight the British Empire.

Despite the earlier clamor for "All Oregon", the Oregon Treaty

was popular in the United States and was easily ratified by the Senate.

The most fervent advocates of manifest destiny had not prevailed along

the northern border because, according to Reginald Stuart, "the compass of manifest destiny pointed west and southwest, not north, despite the use of the term 'continentalism'".

In 1869, American historian Frances Fuller Victor published Manifest Destiny in the West in the Overland Monthly,

arguing that the efforts of early American fur traders and missionaries

presaged American control of Oregon. She concluded the article as

follows:

| “ | It was an oversight on the part of the United States, the giving up the island of Quadra and Vancouver, on the settlement of the boundary question. Yet, "what is to be, will be", as some realist has it; and we look for the restoration of that picturesque and rocky atom of our former territory as inevitable. | ” |

Mexico and Texas

Manifest destiny played an important role in the expansion of Texas and American relationship with Mexico. In 1836, the Republic of Texas declared independence from Mexico and, after the Texas Revolution,

sought to join the United States as a new state. This was an idealized

process of expansion that had been advocated from Jefferson to

O'Sullivan: newly democratic and independent states would request entry

into the United States, rather than the United States extending its

government over people who did not want it. The annexation of Texas was

attacked by anti-slavery spokesmen because it would add another slave

state to the Union. Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren

declined Texas's offer to join the United States in part because the

slavery issue threatened to divide the Democratic Party.

Before the election of 1844, Whig candidate Henry Clay

and the presumed Democratic candidate, former President Van Buren, both

declared themselves opposed to the annexation of Texas, each hoping to

keep the troublesome topic from becoming a campaign issue. This

unexpectedly led to Van Buren being dropped by the Democrats in favor of

Polk, who favored annexation. Polk tied the Texas annexation question

with the Oregon dispute, thus providing a sort of regional compromise on

expansion. (Expansionists in the North were more inclined to promote

the occupation of Oregon, while Southern expansionists focused primarily

on the annexation of Texas.) Although elected by a very slim margin,

Polk proceeded as if his victory had been a mandate for expansion.

All Mexico

American occupation of Mexico City in 1847

After the election of Polk, but before he took office, Congress approved the annexation of Texas. Polk moved to occupy a portion of Texas that had declared independence from Mexico in 1836, but was still claimed by Mexico. This paved the way for the outbreak of the Mexican–American War

on April 24, 1846. With American successes on the battlefield, by the

summer of 1847 there were calls for the annexation of "All Mexico",

particularly among Eastern Democrats, who argued that bringing Mexico

into the Union was the best way to ensure future peace in the region.

This was a controversial proposition for two reasons. First,

idealistic advocates of manifest destiny like John L. O'Sullivan had

always maintained that the laws of the United States should not be

imposed on people against their will. The annexation of "All Mexico"

would be a violation of this principle. And secondly, the annexation of

Mexico was controversial because it would mean extending

U.S. citizenship to millions of Mexicans. Senator John C. Calhoun

of South Carolina, who had approved of the annexation of Texas, was

opposed to the annexation of Mexico, as well as the "mission" aspect of

manifest destiny, for racial reasons. He made these views clear in a speech to Congress on January 4, 1848:

We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race—the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of the kind, of incorporating an Indian race; for more than half of the Mexicans are Indians, and the other is composed chiefly of mixed tribes. I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race.... We are anxious to force free government on all; and I see that it has been urged ... that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the world, and especially over this continent. It is a great mistake.

This debate brought to the forefront one of the contradictions of

manifest destiny: on the one hand, while identitarian ideas inherent in

manifest destiny suggested that Mexicans, as non-whites, would present a

threat to white racial integrity and thus were not qualified to become

Americans, the "mission" component of manifest destiny suggested that

Mexicans would be improved (or "regenerated", as it was then described)

by bringing them into American democracy. Identitarianism was used to

promote manifest destiny, but, as in the case of Calhoun and the

resistance to the "All Mexico" movement, identitarianism was also used

to oppose manifest destiny. Conversely, proponents of annexation of "All Mexico" regarded it as an anti-slavery measure.

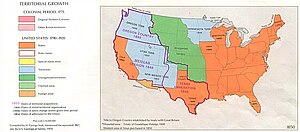

Growth from 1840 to 1850

The controversy was eventually ended by the Mexican Cession, which added the territories of Alta California and Nuevo México

to the United States, both more sparsely populated than the rest of

Mexico. Like the All Oregon movement, the All Mexico movement quickly

abated.

Historian Frederick Merk, in Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation

(1963), argued that the failure of the "All Oregon" and "All Mexico"

movements indicates that manifest destiny had not been as popular as

historians have traditionally portrayed it to have been. Merk wrote

that, while belief in the beneficent mission of democracy was central to

American history, aggressive "continentalism" were aberrations

supported by only a minority of Americans, all of them Democrats. Some

Democrats were also opposed; the Democrats of Louisiana opposed

annexation of Mexico, while those in Mississippi supported it.

Filibusterism

After

the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, disagreements over the

expansion of slavery made further annexation by conquest too divisive to

be official government policy. Some, such as John Quitman,

governor of Mississippi, offered what public support they could offer.

In one memorable case, Quitman simply explained that the state of

Mississippi had "lost" its state arsenal, which began showing up in the

hands of filibusters. Yet these isolated cases only solidified

opposition in the North as many Northerners were increasingly opposed to

what they believed to be efforts by Southern slave owners—and their

friends in the North—to expand slavery through filibustering. Sarah P. Remond on January 24, 1859, delivered an impassioned speech at Warrington, England,

that the connection between filibustering and slave power was clear

proof of "the mass of corruption that underlay the whole system of

American government". The Wilmot Proviso and the continued "Slave Power" narratives thereafter, indicated the degree to which manifest destiny had become part of the sectional controversy.

Without official government support the most radical advocates of manifest destiny increasingly turned to military filibustering. Originally filibuster had come from the Dutch vrijbuiter

and referred to buccaneers in the West Indies that preyed on Spanish

commerce. While there had been some filibustering expeditions into

Canada in the late 1830s, it was only by mid-century did filibuster

become a definitive term. By then, declared the New-York Daily Times

"the fever of Fillibusterism is on our country. Her pulse beats like a

hammer at the wrist, and there's a very high color on her face."

Millard Fillmore's second annual message to Congress, submitted in

December 1851, gave double the amount of space to filibustering

activities than the brewing sectional conflict. The eagerness of the

filibusters, and the public to support them, had an international hue.

Clay's son, a diplomat in Portugal, reported that the invasion created a

sensation in Lisbon.

Filibuster William Walker, who launched several expeditions to Mexico and Central America, ruled Nicaragua, and was captured by the British Navy before being executed in Honduras.

Although they were illegal, filibustering operations in the late

1840s and early 1850s were romanticized in the United States. The

Democratic Party's national platform included a plank that specifically

endorsed William Walker's filibustering in Nicaragua.

Wealthy American expansionists financed dozens of expeditions, usually

based out of New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. The primary

target of manifest destiny's filibusters was Latin America but there

were isolated incidents elsewhere. Mexico was a favorite target of

organizations devoted to filibustering, like the Knights of the Golden

Circle.

William Walker got his start as a filibuster in an ill-advised attempt

to separate the Mexican states Sonora and Baja California. Narciso López, a near second in fame and success, spent his efforts trying to secure Cuba from the Spanish Empire.

The United States had long been interested in acquiring Cuba from the declining Spanish Empire.

As with Texas, Oregon, and California, American policy makers were

concerned that Cuba would fall into British hands, which, according to

the thinking of the Monroe Doctrine, would constitute a threat to the

interests of the United States. Prompted by John L. O'Sullivan, in 1848

President Polk offered to buy Cuba from Spain for $100 million. Polk

feared that filibustering would hurt his effort to buy the island, and

so he informed the Spanish of an attempt by the Cuban filibuster Narciso

López to seize Cuba by force and annex it to the United States, foiling

the plot. Nevertheless, Spain declined to sell the island, which ended

Polk's efforts to acquire Cuba. O'Sullivan, on the other hand eventually

landed in legal trouble.

Filibustering continued to be a major concern for presidents after Polk. Whigs presidents Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore tried to suppress the expeditions. When the Democrats recaptured the White House in 1852 with the election of Franklin Pierce, a filibustering effort by John A. Quitman

to acquire Cuba received the tentative support of the president. Pierce

backed off, however, and instead renewed the offer to buy the island,

this time for $130 million. When the public learned of the Ostend Manifesto

in 1854, which argued that the United States could seize Cuba by force

if Spain refused to sell, this effectively killed the effort to acquire

the island. The public now linked expansion with slavery; if manifest

destiny had once enjoyed widespread popular approval, this was no longer

true.

Filibusters like William Walker continued to garner headlines in the late 1850s, but to little effect. Expansionism was among the various issues that played a role

in the coming of the war. With the divisive question of the expansion

of slavery, Northerners and Southerners, in effect, were coming to

define manifest destiny in different ways, undermining nationalism as a

unifying force. According to Frederick Merk, "The doctrine of Manifest

Destiny, which in the 1840s had seemed Heaven-sent, proved to have been a

bomb wrapped up in idealism."

Homestead Act

The Homestead Act of 1862 encouraged 600,000 families to settle the West by giving them land (usually 160 acres) almost free. They had to live on and improve the land for five years. Before the Civil War, Southern leaders opposed the Homestead Acts because they feared it would lead to more free states and free territories.

After the mass resignation of Southern senators and representatives at

the beginning of the war, Congress was subsequently able to pass the

Homestead Act.

Native Americans

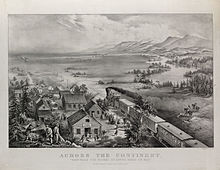

Across The Continent, an 1868 lithograph illustrating the westward expansion of white settlers

Manifest destiny had serious consequences for Native Americans,

since continental expansion implicitly meant the occupation and

annexation of Native American land, sometimes to expand slavery. This

ultimately led to confrontations and wars with several groups of native

peoples via Indian removal. The United States continued the European practice of recognizing only limited land rights of indigenous peoples. In a policy formulated largely by Henry Knox, Secretary of War

in the Washington Administration, the U.S. government sought to expand

into the west through the purchase of Native American land in treaties.

Only the Federal Government could purchase Indian lands and this was

done through treaties with tribal leaders. Whether a tribe actually had a

decision-making structure capable of making a treaty was a

controversial issue. The national policy was for the Indians to join

American society and become "civilized", which meant no more wars with

neighboring tribes or raids on white settlers or travelers, and a shift

from hunting to farming and ranching. Advocates of civilization programs

believed that the process of settling native tribes would greatly

reduce the amount of land needed by the Native Americans, making more

land available for homesteading by white Americans. Thomas Jefferson believed that while American Indians were the intellectual equals of whites, they had to live like the whites or inevitably be pushed aside by them. Jefferson's belief, rooted in Enlightenment

thinking, that whites and Native Americans would merge to create a

single nation did not last his lifetime, and he began to believe that

the natives should emigrate across the Mississippi River and maintain a separate society, an idea made possible by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

In the age of manifest destiny, this idea, which came to be known as "Indian removal",

gained ground. Humanitarian advocates of removal believed that American

Indians would be better off moving away from whites. As historian

Reginald Horsman argued in his influential study Race and Manifest Destiny,

racial rhetoric increased during the era of manifest destiny. Americans

increasingly believed that Native American ways of life would "fade

away" as the United States expanded. As an example, this idea was

reflected in the work of one of America's first great historians, Francis Parkman, whose landmark book The Conspiracy of Pontiac

was published in 1851. Parkman wrote that after the British conquest of

Canada in 1760, Indians were "destined to melt and vanish before the

advancing waves of Anglo-American power, which now rolled westward

unchecked and unopposed". Parkman emphasized that the collapse of Indian

power in the late 18th century had been swift and was a past event.

Beyond North America

Annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898

As the Civil War faded into history, the term manifest destiny experienced a brief revival. Protestant missionary Josiah Strong, in his best seller of 1885 Our Country,

argued that the future was devolved upon America since it had perfected

the ideals of civil liberty, "a pure spiritual Christianity", and

concluded, "My plea is not, Save America for America's sake, but, Save

America for the world's sake."

In the 1892 U.S. presidential election, the Republican Party platform proclaimed: "We reaffirm our approval of the Monroe doctrine and believe in the achievement of the manifest destiny of the Republic in its broadest sense."

What was meant by "manifest destiny" in this context was not clearly

defined, particularly since the Republicans lost the election.

In the 1896 election,

however, the Republicans recaptured the White House and held on to it

for the next 16 years. During that time, manifest destiny was cited to

promote overseas expansion.

Whether or not this version of manifest destiny was consistent with the

continental expansionism of the 1840s was debated at the time, and long

afterwards.

For example, when President William McKinley advocated annexation of the Republic of Hawaii

in 1898, he said that "We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more

than we did California. It is manifest destiny." On the other hand,

former President Grover Cleveland,

a Democrat who had blocked the annexation of Hawaii during his

administration, wrote that McKinley's annexation of the territory was a

"perversion of our national destiny". Historians continued that debate;

some have interpreted American acquisition of other Pacific island

groups in the 1890s as an extension of manifest destiny across the Pacific Ocean. Others have regarded it as the antithesis of manifest destiny and merely imperialism.

Spanish–American War and the Philippines

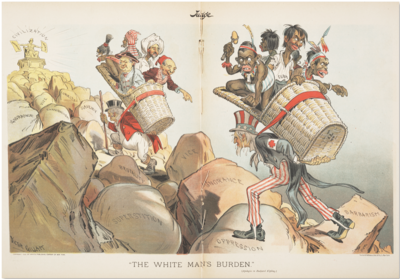

A cartoon of Uncle Sam

seated in restaurant looking at the bill of fare containing "Cuba

steak", "Porto Rico pig", the "Philippine Islands" and the "Sandwich

Islands" (Hawaii).

In 1898, the United States intervened in the Cuban insurrection and launched the Spanish–American War to force Spain out. According to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba and ceded the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam

to the United States. The terms of cession for the Philippines involved

a payment of the sum of $20 million by the United States to Spain. The

treaty was highly contentious and denounced by William Jennings Bryan, who tried to make it a central issue in the 1900 election. He was defeated in landslide by McKinley.

The Teller Amendment,

passed unanimously by the U.S. Senate before the war, which proclaimed

Cuba "free and independent", forestalled annexation of the island. The Platt Amendment (1902), however, established Cuba as a virtual protectorate of the United States.

The acquisition of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines after the war with Spain

marked a new chapter in U.S. history. Traditionally, territories were

acquired by the United States for the purpose of becoming new states on

equal footing with already existing states. These islands, however, were

acquired as colonies rather than prospective states. The process was validated by the Insular Cases.

The Supreme Court ruled that full constitutional rights did not

automatically extend to all areas under American control. Nevertheless,

in 1917, Puerto Ricans were all made full American citizens via the Jones Act.

This also provided for a popularly elected legislature and a bill of

rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner who has a

voice (but no vote) in Congress.

According to Frederick Merk, these colonial acquisitions marked a

break from the original intention of manifest destiny. Previously,

"Manifest Destiny had contained a principle so fundamental that a

Calhoun and an O'Sullivan could agree on it—that a people not capable of

rising to statehood should never be annexed. That was the principle

thrown overboard by the imperialism of 1899." Albert J. Beveridge

maintained the contrary at his September 25, 1900, speech in the

Auditorium, at Chicago. He declared that the current desire for Cuba and

the other acquired territories was identical to the views expressed by

Washington, Jefferson and Marshall. Moreover, "the sovereignty of the

Stars and Stripes can be nothing but a blessing to any people and to any

land."

The Philippines was eventually given its independence in 1946; Guam and

Puerto Rico have special status to this day, but all their people have

United States citizenship.

The English poet Rudyard Kipling wrote "The White Man's Burden"

to Americans, calling on them to take up their share of the burden.

Subtitled "The United States and the Philippine Islands", it was a

widely noted expression of imperialist sentiments, which were common at the time. The nascent revolutionary government desirous of independence, however, resisted the United States in the Philippine–American War in 1899; it won no support from any government anywhere and collapsed when its leader was captured. William Jennings Bryan denounced the war and any form of overseas expansion, writing, "'Destiny' is not as manifest as it was a few weeks ago."

Legacy and consequences

The belief in an American mission to promote and defend democracy throughout the world, as expounded by Thomas Jefferson and his "Empire of Liberty", and continued by Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush, continues to have an influence on American political ideology. Under Douglas MacArthur, the Americans "were imbued with a sense of manifest destiny" says historian John Dower.

The U.S.'s intentions to influence the area (especially the Panama Canal construction and control) led to the separation of Panama from Colombia in 1903

After the turn of the nineteenth century to the twentieth, the phrase manifest destiny declined in usage, as territorial expansion ceased to be promoted as being a part of America's "destiny". Under President Theodore Roosevelt the role of the United States in the New World was defined, in the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,

as being an "international police power" to secure American interests

in the Western Hemisphere. Roosevelt's corollary contained an explicit

rejection of territorial expansion. In the past, manifest destiny had

been seen as necessary to enforce the Monroe Doctrine in the Western

Hemisphere, but now expansionism had been replaced by interventionism as a means of upholding the doctrine.

President Woodrow Wilson

continued the policy of interventionism in the Americas, and attempted

to redefine both manifest destiny and America's "mission" on a broader,

worldwide scale. Wilson led the United States into World War I

with the argument that "The world must be made safe for democracy." In

his 1920 message to Congress after the war, Wilson stated:

... I think we all realize that the day has come when Democracy is being put upon its final test. The Old World is just now suffering from a wanton rejection of the principle of democracy and a substitution of the principle of autocracy as asserted in the name, but without the authority and sanction, of the multitude. This is the time of all others when Democracy should prove its purity and its spiritual power to prevail. It is surely the manifest destiny of the United States to lead in the attempt to make this spirit prevail.

This was the only time a president had used the phrase "manifest

destiny" in his annual address. Wilson's version of manifest destiny was

a rejection of expansionism and an endorsement (in principle) of self-determination,

emphasizing that the United States had a mission to be a world leader

for the cause of democracy. This U.S. vision of itself as the leader of

the "Free World" would grow stronger in the 20th century after World War II, although rarely would it be described as "manifest destiny", as Wilson had done.

"Manifest destiny" is sometimes used by critics of U.S. foreign

policy to characterize interventions in the Middle East and elsewhere.

In this usage, "manifest destiny" is interpreted as the underlying cause

of what is denounced by some as "American imperialism".

A more positive-sounding phrase devised by scholars at the end of the

twentieth century is "nation building", and State Department official

Karin Von Hippel notes that the U.S. has "been involved in

nation-building and promoting democracy since the middle of the

nineteenth century and 'Manifest Destiny'".