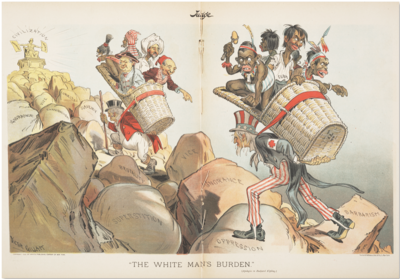

John Bull (Great Britain) and Uncle Sam

(U.S.) bear "The White Man's Burden (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling)", by

delivering the coloured peoples of the world to civilization. (Victor Gillam, Judge magazine, 1 April 1899)

The White Man's Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902), which exhorts the U.S. to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.

Kipling originally wrote the poem to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria (22 June 1897), but it was replaced with the sombre poem "Recessional"

(1897), also a Kipling work about empire. He rewrote "The White Man's

Burden" to encourage American colonization and annexation of the Philippine Islands, a Pacific Ocean archipelago conquered in the three-month Spanish–American War (1898).

As a poet of imperialism, Kipling exhorts the American reader and

listener to take up the enterprise of empire, yet warns about the

personal costs faced, endured, and paid in building an empire; nonetheless, American imperialists understood the phrase The white man's burden to justify imperial conquest as a mission-of-civilisation that is ideologically related to the continental-expansion philosophy of Manifest Destiny.

The title, the subject, and the themes of "The White Man's Burden" provoke accusations of advocacy of the Eurocentric racism inherent to the idea that, by way of industrialisation, the Western world delivers civilisation to the non-white peoples of the world.

History

Rudyard Kipling's poem, "The White Man's Burden", was first published in The Times (London) on 4 February 1899, and in several U.S. newspapers the next day, including The New York Sun.

On 7 February 1899, in the course of senatorial debate to decide (Joint

Resolution S.R. 210) if the U.S. should retain control of the

Philippine Islands and the ten million Filipinos conquered from the Spanish Empire, Senator Benjamin Tillman read aloud the first, fourth, and fifth stanzas of Kipling's eight-stanza poem as arguments against ratification of the Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain (Treaty of Paris);

and that the United States should formally renounce claim of authority

over the Philippine Islands. To that effect, Senator Tillman addressed

the American senators:

The White Man's Burden: civilising the unwilling savage. (Detroit Journal, 1898)

As though coming at the most opportune time possible, you might say, just before the treaty reached the Senate, or about the time it was sent to us, there appeared in one of our magazines a poem by Rudyard Kipling, the greatest poet of England at this time. Mr. President, this poem, unique, and in some places difficult to understand, is to my mind a prophecy. I do not imagine that in the history of human events any poet has ever felt inspired so clearly to portray our danger and our duty. It is called "The White Man's Burden." With the permission of Senators I will read a stanza, and I beg them to listen to it, for it is well worth their attention. This man has lived in the Indies. In fact he is a citizen of the world, and has been all over it, and knows whereof he speaks.

(i) Take up the White Man's burden — / Send forth the best ye breed — / Go bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives' need; / To wait in heavy harness, / On fluttered folk and wild — / Your new-caught, sullen peoples, / Half-devil and half-child.

(iv) Take up the White Man's burden — / No tawdry rule of kings, / But toil of serf and sweeper — / The tale of common things. / The ports ye shall not enter, / The roads ye shall not tread, / Go make them with your living, / And mark them with your dead.

(v) Take up the White Man's burden — / And reap his old reward: / The blame of those ye better, / The hate of those ye guard — / The cry of hosts ye humour / (Ah, slowly!) toward the light: — / "Why brought he us from bondage, / Our loved Egyptian night?"

Those [Filipino] peoples are not suited to our institutions. They are not ready for liberty as we understand it. Why are we bent on forcing upon them a civilization not suited to them, and which only means, in their view, degradation and a loss of self-respect, which is worse than the loss of life itself?

The senator's eloquence was unpersuasive, and the U.S. Congress

ratified the Treaty of Paris on 11 February 1899, which ended the

Spanish–American War. After paying a post-war indemnification of twenty

million dollars to the Kingdom of Spain, on 11 April 1899, the U.S.

established geopolitical hegemony upon islands and peoples in two oceans and in two hemispheres; the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific Ocean, Cuba, and Puerto Rico in the Atlantic Ocean.

The poem

The British poet Rudyard Kipling in Calcutta, India. (1892)

Life magazine cover depicting the water torture of a Filipino PoW, by U.S. Army soldiers in the Philippine Islands. (1902)

"The White (?) Man's Burden" shows the colonial exploitation of labour of the poor nations by the rich nations of the world. (William Henry Walker, Life magazine, 16 March 1899)

- The White Man's Burden — The United States and the Philippine Islands

- by Rudyard Kipling

Take up the White Man's burden —

Send forth the best ye breed —

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild —

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Take up the White Man's burden —

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain

To seek another's profit,

And work another's gain.

Take up the White Man's burden —

The savage wars of peace —

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man's burden —

No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper —

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living,

And mark them with your dead.

Take up the White Man's burden —

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard —

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light: —

"Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?"

Take up the White Man's burden —

Ye dare not stoop to less —

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your gods and you.

Take up the White Man's burden —

Have done with childish days —

The lightly profferred laurel,

The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood

Through all the thankless years

Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom,

The judgment of your peers!

Send forth the best ye breed —

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild —

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

Take up the White Man's burden —

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain

To seek another's profit,

And work another's gain.

Take up the White Man's burden —

The savage wars of peace —

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man's burden —

No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper —

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living,

And mark them with your dead.

Take up the White Man's burden —

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard —

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light: —

"Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?"

Take up the White Man's burden —

Ye dare not stoop to less —

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your gods and you.

Take up the White Man's burden —

Have done with childish days —

The lightly profferred laurel,

The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood

Through all the thankless years

Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom,

The judgment of your peers!

Interpretation

The

American writer Mark Twain replied to the imperialism Kipling espoused

in "The White man's Burden " with the satirical essay "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" (1901), about the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion (1899) in China.

The imperialist interpretation of "The White Man's Burden" (1899)

proposes that the "white race" is morally obligated to rule the "non-white" peoples of planet Earth, and to encourage their progress (economic, social, and cultural) through settler colonialism, which is based upon the Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries displacing the natives' religions:

The implication, of course, was that the Empire existed not for the benefit — economic or strategic or otherwise — of Britain, itself, but in order that primitive peoples, incapable of self-government, could, with British guidance, eventually become civilized (and Christianized).

Kipling positively represents colonial imperialism as the moral

burden of the white race, who are divinely destined to civilise the

brutish, non-white Other who inhabits the barbarous parts of the world; to wit, the seventh and eighth lines of the first stanza misrepresent the Filipinos as "new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child." Despite the chauvinistic nationalism that supported Western imperialism in the 19th century, public moral opposition to Kipling's racialist misrepresentation of the colonial exploitation of labour in "The White Man's Burden" produced the satirical essay "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" (1901), by Mark Twain, which catalogues the Western military atrocities of revenge committed against the Chinese people for their anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901) against abusive European businessmen and Christian missionaries.

Politically, Kipling proffered the poem to New York governor Theodore Roosevelt

(1899–1900) to help him persuade anti-imperialist Americans to accept

the territorial annexation of the Philippine Islands to the United

States. In September 1898, Kipling's literary reputation in the U.S. allowed his promotion of American empire to governor Roosevelt:

Now, go in and put all the weight of your influence into hanging on, permanently, to the whole Philippines. America has gone and stuck a pick-axe into the foundations of a rotten house, and she is morally bound to build the house over, again, from the foundations, or have it fall about her ears.

As Victorian imperial poetry, "The White Man's Burden" thematically corresponds to Kipling's belief that the British Empire (1583–1945) was the Englishman's "Divine Burden to reign God's Empire on Earth"; and celebrates British colonialism as a mission of civilisation that would — eventually — benefit the colonised natives.

Responses

Soap and water are included to the civilizing mission that is the white man's burden. (1890s advert)

In the early 20th century, in addition "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" (1901), Mark Twain's factual satire of the civilizing mission

proposed, justified, and defended in "The White Man's Burden'" (1899),

it was Kipling's jingoism that provoked contemporary poetic parodies that expressed anti-imperialist moral outrage, by critically addressing the white-supremacy racism that is basic to colonial empire; among the literary responses to Kipling are: "The Brown Man's Burden" (February 1899), by the British politician Henry Labouchère; "The Black Man's Burden: A Response to Kipling" (April 1899), by the clergyman H. T. Johnson; and the poem "Take up the Black Man's Burden", by the American educator J. Dallas Bowser.

In the U.S., a Black Man's Burden Association demonstrated to Americans how the colonial mistreatment of Filipino brown people in their Philippine homeland was a cultural extension of the institutional racism of the Jim Crow laws (1863–1965) for the legal mistreatment of black Americans in their U.S. homeland. The very positive popular response to Kipling's jingoism for an American Empire to annex the Philippines as a colony impelled the growth of the American Anti-Imperialist League

in their opposition to making colonial subjects of the Filipinos. In a

21st-century query to Kipling's logic in "The White Man's Burden", the

editor M. J. Akbar asked, "How May We Put it Down?" (2003):

We’ve taken up the white man's burden

Of ebony and brown;

Now will you tell us, Rudyard

How we may put it down?

Such a contemporary perspective was preceded by "The Poor Man's

Burden" (1899), wherein Dr. Howard S. Taylor addresses the negative

psycho-social effects of the imperialist ethos upon the working-class people of an empire. In the social perspective of "The Real White Man's Burden" (1902), the reformer Ernest Crosby addresses the moral degradation (coarsening of affect) consequent to the practice of imperialism; and in "The Black Man's Burden" (1903), the British journalist E. D. Morel reported the Belgian imperial Atrocities in the Congo Free State, which was an African personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium.

In the historical survey of The Black Man's Burden: The White Man in Africa, from the Fifteenth Century to World War I (1920), E. D. Morel's critique of imperial-colony power relations identifies an established cultural hegemony

that determines the weight of the black man's burden and the weight of

the white man's burden in their building a colonial empire. The philosophic perspective of "The Black Man's Burden [A Reply to Rudyard Kipling]" (1920), by the social critic Hubert Harrison, describes moral degradation as a consequence of being a colonized coloured man and of being a white colonizer. Moreover, since the late 20th-century contexts of post-imperial decolonisation and of the developing world, the phrase "The white man's burden" communicates the false good-intentions of Western neo-colonialism for the non-white world: civilisation by colonial domination.