Anglo-Saxon law (Old English ǣ, later lagu "law"; dōm "decree, judgment") is a body of written rules and customs that were in place during the Anglo-Saxon period in England, before the Norman conquest. This body of law, along with early Medieval Scandinavian law and Germanic law, descended from a family of ancient Germanic custom and legal thought. However, Anglo-Saxon law codes are distinct from other early Germanic legal statements—known as the leges barbarorum, in part because they were written in Old English instead of in Latin. The laws of the Anglo-Saxons were the second in medieval Western Europe after those of the Irish to be expressed in a language other than Latin.

History

The native inhabitants of England were Celtic Britons. The unwritten Celtic law was learned and preserved by the Druids, who in addition to their religious role also acted as judges. After the Roman conquest of Britain in the first century, Roman law was operative at least concerning Roman citizens. But the Roman legal system disappeared after the Romans left the island in the 5th century.

In the 5th and 6th century, the Anglo-Saxons migrated from Germany and established several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. These had their own legal traditions based in Germanic law that "owed little if anything" to Celtic or Roman influences. Following the Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons, written law codes or "dooms" were produced. The Christian clergy brought with them the art of letters, writing, and literacy.

The first written Anglo-Saxon laws were issued around 600 by Æthelberht of Kent. Writing in the eighth century, the Venerable Bede comments that Æthelberht created his law code "after the examples of the Romans" (Latin: iuxta exempla Romanorum). This likely refers to Romanised peoples such as the Franks, whose Salic law was codified under Clovis I. As a newly Christian king, Æthelberht's creation of his own law code symbolised his belonging to the Roman and Christian traditions. The actual legislation, however, was not influenced by Roman law. Rather, it converted older customs into written legislation, and, reflecting the role of the bishops in drafting it, protected the church. The first seven clauses deal solely with compensation for the church.

In the 9th century, the Danelaw was conquered by Danes and governed under Scandinavian law. The word law itself derives from the Old Norse word laga. Starting with Alfred the Great (r. 871–899), the kings of Wessex united the other Anglo-Saxon peoples against their common Danish enemy. In the process, they created a single Kingdom of England. This unification process was completed under Æthelstan (r. 924–939). The Norman Conquest of 1066 ended the Anglo-Saxon monarchy. But Anglo-Saxon law and institutions survived and formed the foundation for the common law.

Sources

There were two main sources of Anglo-Saxon law: folk-right (customary law) and royal legislation.

Folk-right

Most laws in Anglo-Saxon England derived from folk-right (Old English: folcright) or unwritten custom. The chief centres for the formulation and application of folk-right were the shire court and hundred courts. As there were no judges in this period, folk-right was administered by the suitors of the court (those required to attend). The reeves employed by the king were responsible for ensuring that folk-right was followed.

The older law of real property, of succession, of contracts, the customary tariffs of fines, were mainly regulated by folk-right. Customary law differed between local cultures. There were different folk-rights of West and East Saxons, of East Angles, of Kentish men, Mercians, Northumbrians, Danes, Welshmen, and these main folk-right divisions remained even when tribal kingdoms disappeared and the people were concentrated in one kingdom.

Folk-right could be broken or modified by special law or special grant, and the fountain of such privileges was the royal power. Alterations and exceptions were, as a matter of fact, suggested by the interested parties themselves, and chiefly by the Church. Thus a privileged land-tenure was created—bookland; the rules as to the succession of kinsmen were set at nought by concession of testamentary power and confirmations of grants and wills; special exemptions from the jurisdiction of the hundreds and special privileges as to levying fines were conferred. In process of time the rights originating in royal grants of privilege overbalanced, as it were, folk-right in many respects, and became themselves the starting-point of a new legal system—the feudal one.

Royal law codes

In addition to folk-right, kings could decree new law in order to clarify the older laws. Royal law codes were written to address specific situations and were intended to be read by people who were already familiar with the law. Anglo-Saxon kings issued regulations about the sale of cattle in the presence of witnesses, enactments about the pursuit of thieves, and the calling in of warrantors to justify sales of chattels. Personal surety groups appear as a complement of and substitute for more collective responsibility. The hlaford and his hiredmen are an institution not only of private patronage, but also of supervision for the sake of laying hands on malefactors and suspected persons.

The first law code was the Law of Æthelberht (c. 602), which put into writing the unwritten legal customs of Kent. This was followed by two later Kentish law codes, the Law of Hlothhere and Eadric (c. 673 – c. 685) and the Law of Wihtred (695). Outside of Kent, Ine of Wessex issued a law code between 688 and 694. Offa of Mercia (r. 757–796) produced a law code that has not survived. Alfred the Great, king of Wessex, produced a law code c. 890 known as the Doom Book. The prologue of Alfred's code states that the Bible and penitentials were studied as part of creating his code. In addition, older law codes were studied, including the laws of Æthelberht, Ine, and Offa. This may have been the first attempt to create a limited set of uniform laws across England, and it set a precedent for future English kings.

The House of Wessex became rulers of all England in the 10th century, and their laws were applied throughout the kingdom. Significant 10th-century law codes were promulgated by Edward the Elder, Æthelstan, Edmund I, Edgar, and Æthelred the Unready. But regional variations in laws and customs survived as well. The Domesday Book of 1086 noted that distinct laws existed for Wessex, Mercia, and the Danelaw.

The law codes of Cnut (r. 1016–1035) were the last to be promulgated in the Anglo-Saxon period and are primarily a collection of earlier laws. They became the main source for old English law after the Norman Conquest. For political reasons, these laws were attributed to Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066), and "under the guise of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris they achieved an almost mystical authority which inspired Magna Carta in 1215 and were for centuries embedded in the coronation oath." The Leges Edwardi Confessoris is the best known of the custumals, compilations of Anglo-Saxon customs written after the Conquest to explain Anglo-Saxon laws to the new Norman rulers.

Features

Kinship

One of the foundations of Anglo-Saxon law was the extended family or kindred (Old English: mægþ). Membership in a kindred provided the individual with protection and security.

In the case of homicide, the victim's family was responsible for avenging him or her through a blood feud. The law set criteria for legitimate blood feuds. A family did not have the right to retaliate if a member was killed while stealing property, committing capital crimes, or resisting capture. A person was exempt from retaliation if he killed while:

- Fighting for his lord

- Protecting his family from attack

- Defending his wife, daughter, sister, or mother from attempted rape (the murder had to take place during the attack)

Kings and the church promoted financial compensation (Old English: bote) for death or injury as an alternative to blood feuds. In the case of death, the victim's family was owed the weregild ("man price"). A person's weregild was greater or lesser depending on social status.

Cnut's code allowed secular clergy to demand or pay compensation in a feud. However, monks were prohibited because they had abandoned their "kin-law when [they bowed] to [monastic] rule-law".

Social class

A man had to own at least five hides of land to be considered a thegn (nobleman). Ealdormen (and later earls) were the highest-ranking nobles. High-ranking churchmen such as archbishops, bishops, and abbots also formed part of the aristocracy.

There were various categories of freemen:

- Geneats performed riding service (carried messages, transported strangers to the village, cared for horses, and acted as the lord's bodyguard)

- Ceorls held one to two hides of land

- Geburs held a virgate of land

- Cotsetlan (cottage dwellers) held five acres

- Homeless laborers were paid in food and clothing

Thegns enjoyed greater rights and privileges than did ordinary freemen. The weregild of a ceorl was 200 shillings while that of a thegn was 1200. In court, a thegn's oath was equal to the oath of six ceorls.

Slavery was widespread in Anglo-Saxon England. The price of a slave (Old English: þēow) or thrall (Old Norse: þræll) was one pound or eight oxen. If a slave was killed, his murderer only had to pay the purchase price because slaves had no wergild. Because slaves had no property, they could not pay fines as a punishment for crime. Instead, slaves received corporal punishments such as flogging, mutilation, or death.

Slavery was an inherited status. The slave population included the conquered Britons and their descendants. Some people were enslaved as war captives or as punishment for crimes (such as theft). Others became slaves due to unpaid debts. While owners had extensive power over their slaves, their power was not absolute. Slaves could be manumitted; however, only 2nd or 3rd-generation descendants of freed slaves received all the privileges of a freeman.

Slavery may have declined in the late eleventh century as it was considered a pious act for Christians to free their slaves on their deathbed. The church condemned the sale of slaves outside the country, and the internal trade declined in the twelfth century. It may have been more economic to settle slaves on land than to feed and house them, and the change to serfdom was probably an evolutionary change in status rather a clear distinction between the two.

Land law

The king granted bookland (so-called because it was granted by charter) to the church or lords in outright ownership. Food rent and other services owed to the king (except for the trinoda necessitas) were transferred to the new lord. Land granted temporarily in exchange for specific services was called loanland.

Lords granted peasants land in return for rent and labor. It was also common for free peasants who owned their land to submit to a lord for protection through a process called commendation. Peasants who commended their land owed their lord labor service. Theoretically, a commended peasant could transfer his land to a new lord whenever he liked. In reality, this was not permitted. By 1066, manorialism was entrenched in England.

Many parts of England (including Kent, East Anglia, and Dorset) practiced forms of partible inheritance in which land was equally divided among heirs. In Kent, this took the form of gavelkind.

Peace and protection

Every house had a peace (Old English: mund). Intruders and other violators of the peace had to pay a fine called a mundbyrd. A man's status determined the amount of the mundbyrd. The laws of Æthelberht set the mundbyrd for the king at 50 shillings, the eorl (noble) at 12s., and the ceorl (freeman) at 6s. In Alfred the Great's time, the king's mundbyrd was £5. Individuals received protection through kinship ties or by entering the service of a lord.

Mund is the origin of the king's peace. Initially, the king's mund was limited to the royal residence. As royal power and responsibilities grew, the king's peace was applied to other areas: shire courts, hundred courts, highways, rivers, bridges, churches, monasteries, markets, and towns. Theoretically, the king was present at these places. King's imposed fines called wites as punishments for breaches of the king's peace.

The king could grant individuals a personal peace (or grith). For example, the king's peace protected his counselors when traveling to and from meetings of the witan. Foreign traders and others not protected by lordship or kinship ties were under the king's protection.

Punishments

Anglo-Saxon law mandated that a person pay compensation when injuring another person. The injured body part determined the amount of compensation. According to Æthelberht's law, pulling someone's hair cost 50 sceattas, a severed foot cost 50 shillings, and "damaging the kindling limb" (the reproductive organs) cost 300 shillings.

In the case of murder, the victim's kindred could forego a blood feud in return for payment of a wergild. In addition to paying the king a wite (fine), the killer also owed compensation to the victim's lord. Some crimes could not be satisfied by financial compensation. These botless crimes were punished with death or forfeiture of property. They included:

- secret murder, such as by poison or witchcraft

- treachery to one's lord

- arson

- house-breaking

- open theft

Hanging by the gallows and beheading were common forms of execution. Murder by witchcraft was punished by drowning. According to the laws of Æthelstan, thieves over 15 years of age who stole more than 12 pence were to be executed (men by stoning, women by burning, and free women could be pushed off a cliff or drowned).

In Cnut's code, a first criminal offence usually merited compensation to victims and fines to the king. Later offenses saw progressively severe forms of bodily mutilation. Cnut also introduced outlawry, a punishment only the king could remove.

Anglo-Saxon law assumed that a man's wife and children were his accomplices in any crime. If a man could not return or pay for stolen property, he and his family could be enslaved.

Religion and the church

The creation of written law codes coincided with Christianisation, and the Anglo-Saxon church received special privileges and protections in the earliest codes. The Law of Æthelberht demanded compensation for offenses against church property:

- 12-fold compensation for church property

- 11-fold for a bishop's property

- 9-fold for a priest's property

- 6-fold for a deacon's property

- 3-fold for a cleric's property

In the late 7th century, the laws of Kent and Wessex supported the church in various ways. Failure to receive baptism was punished with a financial penalty, and the oath of a communicant was worth more than a non-communicant in legal proceedings. Laws supported Sabbath observance and payment of church-scot (church dues). Laws also established rights to church sanctuary .

Courts

Public courts

The Anglo-Saxons developed a sophisticated system of assemblies or moots (the Old English words mot and gemot mean "meeting").

The witan was the king's court. With the advice of his ealdormen, the king gave final judgment in person. He heard cases involving royal property, treason, and appeals from lower courts.

By the tenth century, England was divided into shires. The shire court met twice a year around Easter and Michaelmas. It had jurisdiction over criminal, civil, and ecclesiastical cases. However, most of its work concerned land disputes. The sheriff or sometimes the ealdorman (later earl) and the bishop presided, but there was no judge in the modern sense (royal judges would not sit in shire courts until the reign of Henry I). The local aristocracy controlled the court. The suitors of the court (bishops, earls, and thegns) declared the law and decided what proof of innocence or guilt to accept (such as ordeal or compurgation). The shire court handled administrative business, such as arrangements for collecting geld.

Each shire was divided into smaller units called hundreds. The hundred court met monthly. It handled routine judicial business, civil as well as criminal. It had jurisdiction over land ownership, tort, and ecclesiastical cases (such as disputes over tithes and marriages). People could appeal their cases to the shire court or the king. The sheriff presided two or three times a year, and a subordinate reeve presided at other times. Any landowning freeman could attend the hundred court. However, thegns controlled the court. As suitors to the court, the thegns (or their bailiffs) were responsible for declaring the law, deciding what form of proof to accept, and assisting with the court's administrative functions.

Hundreds were further divided into tithings, which were the responsibilities of tithingmen. Tithings were the basis of a system of self-policing called frankpledge. Every man belonged to a tithing and swore to report crimes committed by those in his tithing on pain of amercement.

Boroughs were separate from the hundreds and had their own courts (variously termed burghmoot, portmanmoot, or husting). These met three times a year. While initially a regular court, the borough court developed into a special court for the law merchant.

Jurisdiction

By the 10th century, certain offenses were considered "pleas of the king". There were two kinds of king's pleas: cases in which the king was a party and cases involving severe crimes reserved to the king's jurisdiction. These cases could only be tried in the presence of the king or royal officials in the shire court or a public hundred court. The laws of Cnut defined king's pleas as:

- violation of the royal protection (mund)

- murder

- treason

- arson

- attacks on houses

- persistent robbery

- counterfeiting

- assault

- harbouring fugitives

- neglect of military service

- fighting

- rape

Private courts

In the Anglo-Saxon period, the king created private courts in two ways.:

- The king could grant the church (either the bishop of a diocese or the abbot of a religious house) the right to administer a hundred. The hundred's reeve would then answer to the bishop or abbot. The same cases would be tried as before, but the profits of justice would now go to the church.

- The king granted by writ or charter special rights to a landowner termed sake and soke. This was the right to hold a court with jurisdiction over his own lands, including infangthief (the power to punish thieves).

The king had the power to revoke these special rights if they were abused.

Trial procedure

Anglo-Saxon England had no professional police. The victim of a crime could raise the hue and cry, "obliging every able-bodied man to do all in his power (pro toto posse suo) to chase and catch the suspect." Once caught, the criminal was taken to court. Suspected criminals could also be brought to court through presentment of crimes as part of the system of frankpledge .Those who fled justice were declared outlaws.

As there were no juries, cases were judged by the suitors of the court. Cases involving land disputes were often decided on the basis of charters and the knowledge of local residents. In cases that lacked evidence or witnesses, courts turned to compurgation and trial by ordeal to determine guilt.

Trial by oath

In the Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England, a false oath was a grave offense against God and could endanger one's immortal soul. In compurgation or trial by oath, a defendant swore oaths to prove his innocence without cross-examination. A defendant was expected to bring oath-helpers (Latin: juratores), neighbors willing to swear to his good character or "oathworthiness". The number of oaths needed depended on the seriousness of the accusation and the person's social status. If the law required oaths valued at 1200 shillings, then a thegn would not need any oath-helpers because his wergild equaled 1200 shillings. However, a ceorl (200 shilling wergild) would need oath-helpers.

A plaintiff initiated legal proceedings by making an accusation (criminal appeal) and summoning the defendant to court. The defendant had to appear in court at the scheduled time or provide an essoin (excuse) for not attending. Once in court, the plaintiff swore the accusation was true (a false accusation was punished with fines). The plaintiff had to provide evidence for the accusation or an adequate number of oath-helpers. If the evidence were strong, no oaths would be required.

Next, the defendant was allowed to deny the accusation under oath and present any required oath-helpers. In Anglo-Saxon law, "denial is always stronger than accusation". The defendant was acquitted if he produced the necessary number of oaths. If a defendant's community believed him to be guilty or generally untrustworthy, he would be unable to gather oath-helpers and would lose his case.

Trial by ordeal

When a defendant failed to establish his innocence by oath in criminal cases (such as murder, arson, forgery, theft and witchcraft), he might still redeem himself through trial by ordeal. Trial by ordeal was an appeal to God to reveal perjury, and its divine nature meant it was regulated by the church. The ordeal had to be overseen by a priest at a place designated by the bishop. The most common forms in England were ordeal by hot iron and ordeal by water. Before a defendant was put through the ordeal, the plaintiff had to establish a prima facie case under oath. The plaintiff was assisted by his own supporters or "suit", who might act as witnesses for the plaintiff.

Influences

The oldest Anglo-Saxon law codes, especially from Kent and Wessex, reveal a close affinity to Germanic law. For example, one finds a division of social ranks reminiscent of the threefold gradation of Lower Germany (edelings, frilings, lazzen—eorls, ceorls, laets).

In subsequent history, there is a good deal of resemblance between the capitularies' legislation of Charlemagne and his successors on one hand, the acts of Alfred, Edward the Elder, Æthelstan and Edgar on the other, a resemblance called forth less by direct borrowing of Frankish institutions than by the similarity of political problems and condition. Frankish law becomes a powerful modifying element in English legal history after the Conquest, when it was introduced wholesale in royal and in feudal courts.

The Scandinavian invasions brought in many northern legal customs, especially in the area known as the Danelaw. The Domesday survey of Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, Norfolk, etc., shows remarkable deviations in local organization and justice (lagmen, sokes), and great peculiarities as to status (socmen, freemen), while from laws and a few charters we can perceive some influence on criminal law (nidings-vaerk), special usages as to fines (lahslit), the keeping of peace, attestation and sureties of acts (faestermen), etc. But, on the whole, the introduction of Danish and Norse elements, apart from local cases, was more important owing to the conflicts and compromises it called forth and its social results than on account of any distinct trail of Scandinavian views in English law. The Scandinavian newcomers coalesced easily and quickly with the native population.

The direct influence of Roman law was not great during the Saxon period: there is neither the transmission of important legal doctrines, chiefly through the medium of Visigothic codes, nor the continuous stream of Roman tradition in local usage. But indirectly Roman law did exert a by no means insignificant influence through the medium of the Church, which, for all its apparent insular character, was still permeated with Roman ideas and forms of culture. The Old English "books" are derived in a roundabout way from Roman models, and the tribal law of real property was deeply modified by the introduction of individualistic notions as to ownership, donations, wills, rights of women, etc. Yet in this respect also the Norman Conquest increased the store of Roman conceptions by breaking the national isolation of the English Church and opening the way for closer intercourse with France and Italy.

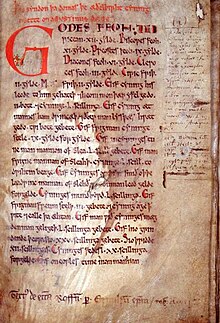

Language and dialect

The English dialect in which the Anglo-Saxon laws have been handed down is in most cases a common speech derived from the West Saxon dialect. Wessex formed the core of the unified Kingdom of England, and the royal court at Winchester became the main literary centre. Traces of the Kentish dialect can be detected the Textus Roffensis, a manuscript containing the earliest Kentish laws. Northumbrian dialectical peculiarities are also noticeable in some codes, while Danish words occur as technical terms in some documents. With the Norman Conquest, Latin took the place of English as the language of legislation, though many technical terms from English for which Latin did not have an equivalent expression were retained.